Research Paper Series No. 160 Proceedings of Seminar on Peter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Undergraduate/Graduate Schools Academic Affairs Handbook

2019 Undergraduate/Graduate Schools Academic Affairs Handbook Center for Academic Affairs Bureau of Academic Affairs, Sophia University When the Public Transportation is shutdown When the university decides that is it not possible to hold regular classes or final exams due to the shutdown of transport services caused by natural disasters such as typhoons, heavy rainfall, accidents or strikes, classes may be canceled and exams rescheduled to another day. Such cancellation and changes will be announced on the university’s official website, Loyola, official Facebook, or Twitter. Offices Related to Academic Affairs The phone numbers listed are extension numbers. Dial 03-3238-刊刊刊刊 (extension number) when calling from an external line. Office Main work handled Location Ext. Affairs related to classes, class cancellations, make-up 1st floor, Bldg. 2 3515 Center for classes, examinations, grading, etc. Academic Affairs Teacher's Lounge 2nd floor, Bldg. 2 3164 Office of Mejiro Mejiro Seibo Campus, 6151 Regarding Mejiro Seibo Campus Seibo Campus 1st floor,Bldg.1 03-3950-6151 Center for Teaching and Affairs related to subjects for the teaching license course and 2nd floor, Bldg. 2 3520 Curator curator license course Credentials Affairs related to loaning of equipment and articles, lost and Office of found, application for use of meeting rooms, etc. 1st floor, Bldg. 2 3112 Property Management of Supply Room (Service hours 8:15䡚19:40) Supply Room Service hours 8:15䡚17:50 1st floor, Bldg. 11 4195 ICT Office Use of COM/CALL rooms, SI room and consultation related 3rd floor, Bldg. 2 3101 (Media Center) to the use of computers Reading and loaning 3510 Library Academic information (Reserve book system) 1st floor, Bldg. -

Guest Editorial

Guest Editorial The issues (Vol.21, No.2 and Vol.21, No.4) of the Journal of Arid Land Studies contain the Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Arid Land (Desert Technology X), held on May 24 - 27 at Hotel Toyoko-Inn Narita Kuko in Narita and held on May 28 at Tokyo University of Agriculture in Tokyo, Japan. The papers presented at the Conference and published in these Proceedings are divided into 10 categories; (1) Controlling the Alien Invasive Species (2) Soil Management (3) Valorization of BioResources (4) Vegetation (5) Hydrology (6) Food Production (7) Desertification and Meteorology (8) Water Management and Energy (9) Arid Land Water Cycle (10) Culture and Life Within each session, a broad diversity of scientific researches, innovative technologies, new applications of technologies and important social perspectives were presented. This reflects the multi-disciplinary approach that will be required to address the challenges toward sustainable management of desert, arid and semiarid regions. The current issue (Vol.21, No.2) contains the proceedings of the Keynote Lectures and Joint International Symposium with JAALS. The draft manuscripts of papers were reviewed by two anonymous reviewers after Conference, except the memorial papers for Prof. Kobori. Revised versions of the papers were then resubmitted. If the manuscripts were revised satisfactorily, they were accepted for publication. The Conference Editorial Panel acknowledges the vital contributions of the following reviewers; List of Reviewers Yukuo ABE, University of Tsukuba, Japan, Majed ABU-ZREIG, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Jordan Ould Ahmed BOUYA AHMED, Institute of Superior Education and Technologies, Mauritania Mingyang DU, National Institute for Agro-Environmental Sciences, Japan Yasuyuki EGASHIRA, Osaka University, Japan Hany A. -

The Saddharmapundarika and Its Influence

THE SADDHARMAPUNDARIKA AND ITS INFLUENCE By Senchu Murano The following paper is a summary of Hokekyo no Shiso to Bunka, edited by Yukio Sakamoto, Dean of the Faculty of Buddhism at Rissho University,Tokyo. (Kyoto,Heirakuji-shoten,1965; 711 pp., Index 31 pp.; Yen 4,000.) PA RT I : THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF THE SADDHARMAPUNDARIKA Chapter L The Formation of the Saddharmapunda?'lka A. The Saddharmapundarika and Indian Culture ( Ensho K anakura) H. Kern holds that the character of the Saddharmapundarika is similar to that of Narayana in the Bhagavadglta and that the Bhagavadglta had great influence on the Saddharmapun darika. Winternitz points out the influence of the Purdnas on the stitra, and Farquhar thinks that the Vedantas influenced the sutra. Kern shows us the materials for his opinion, but W inter nitz and Farquhar do not. On the other hand,Charles Eliot and H. von Glasenapp do speak of the influences of other religions on this sutra. They try to find the sources of the philosophy of the Saddharma pundarika in the current thought of India of the time. This is more convincing. It seems to be true to some extent that the Saddharmapun- — 315 — Senchu Murano dartka was influenced by the Bhagavadglta. It is also true, however, that the monotheistic idea given in the Bhagavadglta was already apparent in the Svetasvatara Upanisad, and that monotheism prevailed in India for some centuries around the beginning of the Christian Era. W e can say that the Saddhar- mapundarlka^ the Bhagavadglta, and other pieces of literature of a similar nature were produced from the common ground of the same age. -

Charismatic Leadership and Democratization : a Weberian Perspective 1

CHARISMATIC LEADERSHIP AND DEMOCRATIZATION : A WEBERIAN PERSPECTIVE 1 Michael Bernhar d Associate Professor of Political Science The Pennsylvania State University SUMMARY 2 In at least three cases of democratization in Eastern and Central Europe (ECE), charismati c leaders have played an important role in overthrowing the old regime and in shaping the pattern of new institutions . In addition to Lech Wa łęsa in Poland, Vaclav Havel of the Czech (and formerly Slovak) Republic, and Boris Yeltsin of Russia, can be classified as charismatic leaders with littl e controversy . While there are other charismatic leaders in the region, their commitments t o democracy are quite shaky, and thus they fall outside the scope of this paper . The greatest contribution to our understanding of charisma as a social force has been the wor k of Max Weber. His sociological writings on charisma serve as the point of departure for this paper . After surveying Weber's analysis of charisma, this study turns to what his writings tell us about th e relationship between charisma and democracy. It then addresses the question of the impact tha t democratization has on charismatic leadership and use this to interpret the political fortunes of Lec h Wałęsa, Vaclav Havel, and Boris Yeltsin . It concludes with a discussion of the role of charisma i n both democracy and dictatorship in the contemporary era . Despite their pivotal role in the demise of the communist regimes in their countries and thei r leadership during key phases of the democratization process, none of the three leaders have bee n fully successful in translating their visions for their respective countries into reality . -

11. Comparative Law

DEVELOPMENTS IN 2009 ― ACADEMIC SOCIETIES 109 (10)“Global Risk and the World Order” Hirohide Takigawa(Professor, Osaka City University) (11)“Comment” Taku Morimoto(Lecturer, Health Sciences University of Hokkaido) (12)“Symposium: The Risk Society and Law” 11. Comparative Law I. The Japan Society of Comparative Law held its 72nd General Meeting at Kanagawa University on June 6 and 7, 2009. First Day 1. Anglo-American Law Section: (1)“The Principle of Good Faith in American Law” Yuko Funakoshi(Lecturer, Okinawa International University). (2)“Function and Significance of Protective Order in the Discovery” Harumi Takebe(Doctral Course, Kwansei Gakuin University). (3)“Legal Policy for Brown Field Problems in America ― Comparison between Federal Law and California State Law and its Indications for Japan” Kumiko Fukuda(Doctral Course, Waseda University). 2. Continental Law Section: (1)“Neues Kaufgewahrleistungsrecht und Wahlrecht des Insolvenzverwalters” Koichi Tamura(Associate Professor, Kumamoto University). (2)“Des restitutions en droit civil français” Tetsushi Saito(Associate Professor, Hokkaido University). 3. Socialist Law Section: (1)“Trail for Khmer Rouge and the Future Tasks of Cambodian Judicial System” Kuong Teilee(Associate Professor, Nagoya University). 110 WASEDA BULLETIN OF COMPARATIVE LAW Vol. 29 (2)“The Relationship between International Covenants on Human Rights and Domestic Law in China” Tetsuya Ouchi(Lecturer, Hokuriku University). 4.Mini-Symposium A: “Reference and Invocation of Foreign Law and International Law in the Supreme Court of the United States” (1)“Introduction” Shigeo Miyagawa(Professor, Waseda University). (2)“Significance of Reference to Foreign Laws at the Constitutional Judgment in Capital Punishment ― With Roper v. Simmons(2005)as a Starting Point” Takuya Katsuta(Associate Professor, Osaka City University). -

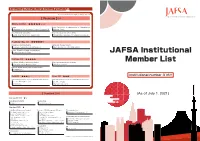

JAFSA Institutional Member List

Supporting Member(Social Business Partners) 43 ※ Classified by the company's major service [ Premium ](14) Diamond( 4) ★★★★★☆☆ Finance Medical Certificate for Visa Immunization for Studying Abroad Western Union Business Solutions Japan K.K. Hibiya Clinic Global Student Accommodation University management and consulting GSA Star Asia K.K. (Uninest) Waseda University Academic Solutions Corporation Platinum‐Exe( 3) ★★★★★☆ Marketing to American students International Students Support Takuyo Corporation (Lighthouse) Mori Kosan Co., Ltd. (WA.SA.Bi.) Vaccine, Document and Exam for study abroad Tokyo Business Clinic JAFSA Institutional Platinum( 3) ★★★★★ Vaccination & Medical Certificate for Student University management and consulting Member List Shinagawa East Medical Clinic KEI Advanced, Inc. PROGOS - English Speaking Test for Global Leaders PROGOS Inc. Gold( 2) ★★★☆ Silver( 2) ★★★ Institutional number 316!! Global Human Resources services・Study Abroad Information Global Human Resources services・Study Abroad Information Access Nextage Co.,Ltd Doorkel Co.,Ltd. DISCO Inc. Mynavi Corporation [ Standard ](29) (As of July 1, 2021) Standard20( 2) ★☆ Study Abroad Information Housing・Hotel Keibunsha MiniMini Corporation . Standard( 27) ★ Study Abroad Program and Support Insurance / Risk Management /Finance Telecommunication Arc Three International Co. Ltd. Daikou Insurance Agency Kanematsu Communications LTD. Australia Ryugaku Centre E-CALLS Inc. Berkeley House Language Center JAPAN IR&C Corporation Global Human Resources Development Fuyo Educations Co., Ltd. JI Accident & Fire Insurance Co., Ltd. JTB Corp. TIP JAPAN Fourth Valley Concierge Corporation KEIO TRAVEL AGENCY Co.,Ltd. Tokio Marine & Nichido Fire Insurance Co., Ltd. Originator Co.,Ltd. OKC Co., Ltd. Tokio Marine & Nichido Medical Service Co.,Ltd. WORKS Japan, Inc. Ryugaku Journal Inc. Sanki Travel Service Co.,Ltd. Housing・Hotel UK London Study Abroad Support Office / TSA Ltd. -

HORIUCHI, Kenji

CURRICULUM VITAE Kenji HORIUCHI University of Shizuoka, Associate Professor Faculty of International Relations, Department of Languages and Cultures (Asian culture course) Graduate School of International Relations Email: [email protected] Address: 52-1 Yada, Suruga-ku, Shizuoka-Shi, 422-8526 JAPAN Education 2006.2 Doctor of Philosophy in Social Sciences, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan 1998.3 Master of Arts in Social Sciences, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan 1991.3 Bachelor of Arts in Literature, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan Employment 2016.4- Associate Professor, School of International Relations, University of Shizuoka 2014.4- Adjunct Researcher, Organization for Regional and Inter-regional Studies, Waseda University 2014.4- Part-time lecturer, Graduate School of Political Science, Kokushikan University 2013.4-2016.3 Part-time lecturer, Komazawa University 2013.4-2015.3 Part-time lecturer, College of Commerce, Nihon University 2011.4-2012.3 Junior researcher, Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies (Assistant Professor at Global-COE Program), Waseda University. 2010.4-2011.3 Adjunct researcher, Overseas Legislative Information Division, Research and Legislative Reference Bureau, National Diet Library 2007.4-2010.3 Assistant Professor, School of Social Sciences, Waseda University 2007.4-2016.3 Part-time lecturer, Rissho University 2003.1-2007.3 Research Associate, Graduate School of Political Science (COE researcher at COE Program), Waseda University 2000.4-2002.3 Research Associate, School of Social Sciences, Waseda University Field of research Central-local relations, regional policy and local politics in Russia (Russian Far East); International Relations in Northeast Asia; Energy Diplomacy Publications (Books) K. Horiuchi, D. Saito and T. Hamano eds., Roshia kyokuto handobukku [Handbook of the Russian Far East], Tokyo: Toyo Shoten, August 2012 (in Japanese). -

Application Guidelines for Rissho University Student Exchange Program 2019 Spring

Application Guidelines for Rissho University Student Exchange Program 2019 Spring Rissho University accepts short-term international exchange students from partner universities / institutions abroad (within one year in principle). This program enables exchange students to take classes at each Faculty of Rissho University. All classes are conducted in Japanese. Exchange students will be given the chance to interact with the students and staff of Rissho University and deepen their understanding of Japan and become active individuals in today's international society. 1. Qualifications for Applicants Applicants must meet all of the following requirements. (1) Is a registered student at a partner university / institution of Rissho University (2) Is a student who is required to earn credits at Rissho University (3) Is able to submit one or more of the following documents to verify Japanese proficiency. a) Certificate of EJU (Examination for Japanese University Admission for International Students) with the score of 220 or higher on "Japanese as a Foreign Language" b) Certificate of JLPT (Japanese Language Proficiency Test) "Level N1" with the score of 145 or higher * Please consult us if the student is not able to demonstrate their Japanese language skills by providing their EJU or JLPT results but has the equal language ability. * If the student's Japanese language proficiency does not meet the above requirements, they are able to take the Japanese Language Program course (please refer to the Application Guidelines for Rissho University Japanese-Language Program Semester Course). 2. Requirements for taking classes available at each faculty Faculty of Buddhist Studies Must have basic knowledge of Buddhist Studies or Nichiren Buddhism. -

11. About the Authors.Pdf (38.63KB)

July 24, 2008 15:40 B-606 abt_auth About the Authors ∗ Akira Ishikawa (Introduction, Chapter 5) Professor Emeritus at Aoyama Gakuin University. Senior Research Fellow at the University of Texas ICC Institute. Awarded a Ph.D. in Business Management from the Graduate School of Business Administration of the University of Texas. Completed postdoctoral studies at MIT.Fields of expertise include management science, man- agement accounting, crisis management, research and development management, and accounting and finance for contents businesses. Principal book: Theory of Strategic Budgetary Control, Dobunkan, 1993. Thesis: Understanding Intellectual Capital and the Model- ing Approach to Intellectual Capital Management, Aoyama Man- agement Review, 2003. Over 70 publications comprise translations or works in which the author has written or edited. Over 400 theses published. Further details of the author can be found at http://www.brainsbank.net/ishikawa. Junpei Nakagawa (Chapter 2) Associate Professor at the Business Administration Department of Komazawa University. Acquired units for a Ph.D. degree in Eco- nomics from the Graduate School of The University of Tokyo. Fields of expertise are institutional economics and organizational theory. Principal book: Institutions and Organizations (co-author, 309 July 24, 2008 15:40 B-606 abt_auth 310 Creative Marketing for New Product and New Business Development editor: Tokutaro Shibata), Sakurai Shoten Publishing, 2007. Thesis: Rethinking the Technostructure Theory, Annual Report of the Society of Economic Sociology, No. 23, September 2001, etc. Hiromichi Yasuoka (Chapter 3) Senior consultant at the Financial Business Consulting Department of the Nomura Research Institute. Awarded an M.S. in Science and Engineering from the Graduate School of Keio University. -

Alfred Weber, Theory of the Location of Industries, 1909

UC Santa Barbara CSISS Classics Title Alfred Weber, Theory of the Location of Industries, 1909. CSISS Classics Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1k3927t6 Author Fearon, David Publication Date 2002 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California CSISS Classics - Alfred Weber: Theory of the Location of Industries, 1909 Alfred Weber: Theory of the Location of Industries, 1909 By David Fearon Background Alfred Weber (1868–1958), like his older brother Max Weber, started his academic career in Germany as an economist, then became a sociologist. While schooled at a time when European economics was emphasizing historical analysis, Weber was among those reintroducing theory and causal models to the field. He is best remembered, particularly in economics, regional science and operations research, for early models of industrial location (discussed below). When his work turned to sociology, however, Weber maintained a commitment to the "philosophy of history" traditions, developing theories for analyzing social change in Western civilization as a confluence of civilization (intellectual and technological), social processes (organizations) and culture (art, religion, and philosophy). He also published empirical and historical analyses of the growth and geographical distribution of cities and capitalism. Weber remained in Nazi Germany during the war, but was a leader in intellectual resistance. After the war his writings and teaching was influential both in and out of academic circles in promoting a philosophical and political recovery for the German people. Innovation With the publication of Über den Standort der Industrie (Theory of the Location of Industries) in 1909, Alfred Weber put forth the first developed general theory of industrial location [references here are to the 1929 translation of the 1909 book by Carl Friedrich]. -

Weber's Ideal Types and Idealization

Weber’s ideal types and idealization Juraj Halas Max Weber’s “ideal types” (its) have long drawn the attention of philosophers of science. Proponents of the Poznan School have formulated at least two different methodological reconstructions of Weber’s conception. One, by Izabella Nowakowa, views its as extreme elements of classifications and argues that the procedure employed in constructing its is but a special case of the method of idealization. Another, by Leszek Nowak, explicates ideal-typical statements as analytic statements which perform explanatory or heuristic functions. In this paper, I assess these reconstructions and confront them with Weber’s original writings. I show that both are inadequate and propose a new one, based on a revised conception of abstraction and idealization. I show that the heuristic function of its, as discussed by Weber, consists in their role in formulating contrastive explanations. This work was supported by the Slovak Research and Development Agency under the contract No. APVV-0149-12. Introduction Max Weber’s writings on “ideal types” (its) have been an important influence in the debates on the philosophy and methodology of social sciences and the hu- manities. In the context of the Poznan School of philosophy of science, at least two contributions to the reconstruction of its have emerged. Unlike Hempel, both emphasize the role of idealization. The historically prior approach is due to Leszek Nowak and was first formulated in English in his (1980). The second approach was presented by Izabella Nowakowa in (2007). This paper critically examines both contributions. In the first part, I briefly restate the accounts weber’s ideal types and idealization 2 and argue that neither of them adequately captures the intent of Weber’s con- ception. -

American Council on Science & Education – CSCE 2021

American Council on Science and Education (ACSE) Printed in the United States of America Copyright CSREA Press https://www.american-cse.org/csce2021/program TABLE OF CONTENTS The 2021 World Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering, and Applied Computing (CSCE'21) July 26-29, 2021, Luxor (MGM), Las Vegas, USA https://american-cse.org/csce2021/ GENERAL INFORMATION: .......................................... 1 IMPORTANT Information about this program/schedule book: ........ 1 REGISTRATION: ................................................ 1 BREAKFASTS: .................................................. 1 DINNER: ...................................................... 1 BREAKS: ...................................................... 1 July 26 (Monday) On-Site Presentations: ...................2 July 26 (Monday) ZOOM; On-Line Presentations: .............6 July 27 (Tuesday) On-Site Presentations: .................13 July 27 (Tuesday) ZOOM; On-Line Presentations: ...........17 July 28 (Wednesday) On-Site Presentations: ...............23 July 28 (Wednesday) ZOOM; On-Line Presentations: .........27 July 29 (Thursday) On-Site Presentations: ................33 July 29 (Thursday) ZOOM; On-Line Presentations: ..........37 American Council on Science & Education – CSCE 2021 GENERAL INFORMATION IMPORTANT: To prepare the congress program/schedule, the title of all papers, authors names, affiliations were extracted from the meta-data of the draft paper submissions (manuscripts submitted by the authors for evaluation). Any changes to the titles of