The Saddharmapundarika and Its Influence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guest Editorial

Guest Editorial The issues (Vol.21, No.2 and Vol.21, No.4) of the Journal of Arid Land Studies contain the Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Arid Land (Desert Technology X), held on May 24 - 27 at Hotel Toyoko-Inn Narita Kuko in Narita and held on May 28 at Tokyo University of Agriculture in Tokyo, Japan. The papers presented at the Conference and published in these Proceedings are divided into 10 categories; (1) Controlling the Alien Invasive Species (2) Soil Management (3) Valorization of BioResources (4) Vegetation (5) Hydrology (6) Food Production (7) Desertification and Meteorology (8) Water Management and Energy (9) Arid Land Water Cycle (10) Culture and Life Within each session, a broad diversity of scientific researches, innovative technologies, new applications of technologies and important social perspectives were presented. This reflects the multi-disciplinary approach that will be required to address the challenges toward sustainable management of desert, arid and semiarid regions. The current issue (Vol.21, No.2) contains the proceedings of the Keynote Lectures and Joint International Symposium with JAALS. The draft manuscripts of papers were reviewed by two anonymous reviewers after Conference, except the memorial papers for Prof. Kobori. Revised versions of the papers were then resubmitted. If the manuscripts were revised satisfactorily, they were accepted for publication. The Conference Editorial Panel acknowledges the vital contributions of the following reviewers; List of Reviewers Yukuo ABE, University of Tsukuba, Japan, Majed ABU-ZREIG, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Jordan Ould Ahmed BOUYA AHMED, Institute of Superior Education and Technologies, Mauritania Mingyang DU, National Institute for Agro-Environmental Sciences, Japan Yasuyuki EGASHIRA, Osaka University, Japan Hany A. -

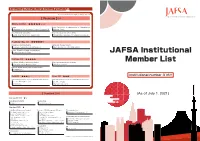

JAFSA Institutional Member List

Supporting Member(Social Business Partners) 43 ※ Classified by the company's major service [ Premium ](14) Diamond( 4) ★★★★★☆☆ Finance Medical Certificate for Visa Immunization for Studying Abroad Western Union Business Solutions Japan K.K. Hibiya Clinic Global Student Accommodation University management and consulting GSA Star Asia K.K. (Uninest) Waseda University Academic Solutions Corporation Platinum‐Exe( 3) ★★★★★☆ Marketing to American students International Students Support Takuyo Corporation (Lighthouse) Mori Kosan Co., Ltd. (WA.SA.Bi.) Vaccine, Document and Exam for study abroad Tokyo Business Clinic JAFSA Institutional Platinum( 3) ★★★★★ Vaccination & Medical Certificate for Student University management and consulting Member List Shinagawa East Medical Clinic KEI Advanced, Inc. PROGOS - English Speaking Test for Global Leaders PROGOS Inc. Gold( 2) ★★★☆ Silver( 2) ★★★ Institutional number 316!! Global Human Resources services・Study Abroad Information Global Human Resources services・Study Abroad Information Access Nextage Co.,Ltd Doorkel Co.,Ltd. DISCO Inc. Mynavi Corporation [ Standard ](29) (As of July 1, 2021) Standard20( 2) ★☆ Study Abroad Information Housing・Hotel Keibunsha MiniMini Corporation . Standard( 27) ★ Study Abroad Program and Support Insurance / Risk Management /Finance Telecommunication Arc Three International Co. Ltd. Daikou Insurance Agency Kanematsu Communications LTD. Australia Ryugaku Centre E-CALLS Inc. Berkeley House Language Center JAPAN IR&C Corporation Global Human Resources Development Fuyo Educations Co., Ltd. JI Accident & Fire Insurance Co., Ltd. JTB Corp. TIP JAPAN Fourth Valley Concierge Corporation KEIO TRAVEL AGENCY Co.,Ltd. Tokio Marine & Nichido Fire Insurance Co., Ltd. Originator Co.,Ltd. OKC Co., Ltd. Tokio Marine & Nichido Medical Service Co.,Ltd. WORKS Japan, Inc. Ryugaku Journal Inc. Sanki Travel Service Co.,Ltd. Housing・Hotel UK London Study Abroad Support Office / TSA Ltd. -

HORIUCHI, Kenji

CURRICULUM VITAE Kenji HORIUCHI University of Shizuoka, Associate Professor Faculty of International Relations, Department of Languages and Cultures (Asian culture course) Graduate School of International Relations Email: [email protected] Address: 52-1 Yada, Suruga-ku, Shizuoka-Shi, 422-8526 JAPAN Education 2006.2 Doctor of Philosophy in Social Sciences, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan 1998.3 Master of Arts in Social Sciences, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan 1991.3 Bachelor of Arts in Literature, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan Employment 2016.4- Associate Professor, School of International Relations, University of Shizuoka 2014.4- Adjunct Researcher, Organization for Regional and Inter-regional Studies, Waseda University 2014.4- Part-time lecturer, Graduate School of Political Science, Kokushikan University 2013.4-2016.3 Part-time lecturer, Komazawa University 2013.4-2015.3 Part-time lecturer, College of Commerce, Nihon University 2011.4-2012.3 Junior researcher, Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies (Assistant Professor at Global-COE Program), Waseda University. 2010.4-2011.3 Adjunct researcher, Overseas Legislative Information Division, Research and Legislative Reference Bureau, National Diet Library 2007.4-2010.3 Assistant Professor, School of Social Sciences, Waseda University 2007.4-2016.3 Part-time lecturer, Rissho University 2003.1-2007.3 Research Associate, Graduate School of Political Science (COE researcher at COE Program), Waseda University 2000.4-2002.3 Research Associate, School of Social Sciences, Waseda University Field of research Central-local relations, regional policy and local politics in Russia (Russian Far East); International Relations in Northeast Asia; Energy Diplomacy Publications (Books) K. Horiuchi, D. Saito and T. Hamano eds., Roshia kyokuto handobukku [Handbook of the Russian Far East], Tokyo: Toyo Shoten, August 2012 (in Japanese). -

Application Guidelines for Rissho University Student Exchange Program 2019 Spring

Application Guidelines for Rissho University Student Exchange Program 2019 Spring Rissho University accepts short-term international exchange students from partner universities / institutions abroad (within one year in principle). This program enables exchange students to take classes at each Faculty of Rissho University. All classes are conducted in Japanese. Exchange students will be given the chance to interact with the students and staff of Rissho University and deepen their understanding of Japan and become active individuals in today's international society. 1. Qualifications for Applicants Applicants must meet all of the following requirements. (1) Is a registered student at a partner university / institution of Rissho University (2) Is a student who is required to earn credits at Rissho University (3) Is able to submit one or more of the following documents to verify Japanese proficiency. a) Certificate of EJU (Examination for Japanese University Admission for International Students) with the score of 220 or higher on "Japanese as a Foreign Language" b) Certificate of JLPT (Japanese Language Proficiency Test) "Level N1" with the score of 145 or higher * Please consult us if the student is not able to demonstrate their Japanese language skills by providing their EJU or JLPT results but has the equal language ability. * If the student's Japanese language proficiency does not meet the above requirements, they are able to take the Japanese Language Program course (please refer to the Application Guidelines for Rissho University Japanese-Language Program Semester Course). 2. Requirements for taking classes available at each faculty Faculty of Buddhist Studies Must have basic knowledge of Buddhist Studies or Nichiren Buddhism. -

American Council on Science & Education – CSCE 2021

American Council on Science and Education (ACSE) Printed in the United States of America Copyright CSREA Press https://www.american-cse.org/csce2021/program TABLE OF CONTENTS The 2021 World Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering, and Applied Computing (CSCE'21) July 26-29, 2021, Luxor (MGM), Las Vegas, USA https://american-cse.org/csce2021/ GENERAL INFORMATION: .......................................... 1 IMPORTANT Information about this program/schedule book: ........ 1 REGISTRATION: ................................................ 1 BREAKFASTS: .................................................. 1 DINNER: ...................................................... 1 BREAKS: ...................................................... 1 July 26 (Monday) On-Site Presentations: ...................2 July 26 (Monday) ZOOM; On-Line Presentations: .............6 July 27 (Tuesday) On-Site Presentations: .................13 July 27 (Tuesday) ZOOM; On-Line Presentations: ...........17 July 28 (Wednesday) On-Site Presentations: ...............23 July 28 (Wednesday) ZOOM; On-Line Presentations: .........27 July 29 (Thursday) On-Site Presentations: ................33 July 29 (Thursday) ZOOM; On-Line Presentations: ..........37 American Council on Science & Education – CSCE 2021 GENERAL INFORMATION IMPORTANT: To prepare the congress program/schedule, the title of all papers, authors names, affiliations were extracted from the meta-data of the draft paper submissions (manuscripts submitted by the authors for evaluation). Any changes to the titles of -

International Perspectives in Geography

International Perspectives in Geography AJG Library Volume 16 Editor-in-Chief Yuji Murayama, The University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Japan Series Editors Yoshio Arai, Teikyo University, Utsunomiya, Japan Hitoshi Araki, Ritsumeikan University, Kusatsu, Japan Shigeko Haruyama, Mie University, Tsu, Japan Yukio Himiyama, Hokkaido University of Education, Sapporo, Japan Mizuki Kawabata, Keio University, Tokyo, Japan Taisaku Komeie, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan Jun Matsumoto, Tokyo Metropolitan University, Tokyo, Japan Takashi Oguchi, The University of Tokyo, Kashiwa, Japan Toshihiko Sugai, The University of Tokyo, Kashiwa, Japan Atsushi Suzuki, Rissho University, Kumagaya, Japan Teiji Watanabe, Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan Noritaka Yagasaki, Nihon University, Tokyo, Japan Satoshi Yokoyama, Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan Aim and Scope The AJG Library is published by Springer under the auspices of the Association of Japanese Geographers. This is a scholarly series of international standing. Given the multidisciplinary nature of geography, the objective of the series is to provide an invaluable source of information not only for geographers, but also for students, researchers, teachers, administrators, and professionals outside the discipline. Strong emphasis is placed on the theoretical and empirical understanding of the changing relationships between nature and human activities. The overall aim of the series is to provide readers throughout the world with stimulating and up-to-date scientific outcomes mainly by Japanese and other Asian geographers. Thus, an “Asian” flavor different from the Western way of thinking may be reflected in this series. The AJG Library will be available both in print and online via SpringerLink. About the AJG The Association of Japanese Geographers (AJG), founded in 1925, is one of the largest and leading organizations on geographical research in Asia and the Pacific Rim today, with around 3000 members. -

Monday June 27, 2016

Monday June 27, 2016 08:00-17:30 Registration 09:00-9:30 Coffee Break 9:30-10:00 Opening Ceremony| Dusit Thani Hall Associate Professor Chalermwat Tantasavasdi Dean, Faculty of Architecture and Planning, Thammasat University Professor Dr. Budy P. Resosudarmo RSAI & PRSCO 10:00-11:00 Keynote Lecture| Dusit Thani Hall Dr. Porametee Vimolsiri Secretary General, Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board 11:00-11:15 Photo Session 11:15-13:00 Lunch Break| 22 Kitchen & Bar (22rd Floor) 12:00-13:00 PRSCO Council Meeting (Invitation only) |TBA 13:00-17:30 Workshop: Satellite and Airborne Remote Sensing to Support Social Science Research| Dusit Thani Hall Organizer: Dr. Gang Chen, University of North Carolina at Charlotte 15:00-15:15 Coffee Break 18:00-20:00 Reception |TBA Tuesday June 28, 2016 08:00-17:30 Registration 08:30-10:00 1. Energy, Development, and Sustainability I| Room: Bangrak Chair: Kim N. Irvine, Nanyang Technological University • Treatment Efficiency and System Dynamics of an Aerated Lagoon/Wetland Wastewater Treat- ment System, Cha-Am, Thailand. Kanha But, Mahidol University; Ranjna Jindal, Mahidol University; Kim N. Irvine, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore; Nawatch Surinkul, Mahidol University • Managing The Waterscapes of Urban Asia: Challenges and Lessons Learned in Sustainability. Kim N. Irvine, Nanyang Technological University; Diganta Das, Nanyang Technological University • Sustainable Landscape Design: Learning from Cha-am. Asan Suwanarit, Thammasat University; Alisa Sahawatcharin, Thammasat University; Fa Likitswat, Thammasat University • Model Simulation of the Policy Evaluation for the Improvement of the Water Environment in the River Basin. Katsuhiro Sakurai, Rissho University; Hiroyuki Shibusawa, Toyohashi University of Technology Discussants: Katsuhiro Sakurai, Rissho University, [email protected] Kanha But, Mahidol University, [email protected] Kim N. -

Economic Associations the Union of National in Japan

No.34 ISSN 0289 - 8721 NAL ECO IO N T O Information Bulletin of A M N I C F A O The Union of National S N S O O I C N I A Economic Associations U T E I O H T N S in Japan 日本経済学会連合 2014 Correspondence to be addressed: Secretariat of the Union of National Economic Associations in Japan, c/o International Business Institute Co., Ltd. Tsukasa Building 3rd. F. , 518 Waseda Tsurumaki-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 162-0041, Japan e-mail: [email protected] COPYRIGHT 2014 BY THE UNION OF NATIONAL ECONOMIC ASSOCIATIONS IN JAPAN Printed in Japan. INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS INSTITUTE, CO., LTD. Tel. +81-3- 5273-0473 ISSN 0289-8721 Editorial Committee Managing Editor Yoshiharu KUWANA, J. F. Oberlin University Mamoru KOBAYASHI, Senshu University Kappei HIDAKA, Chuo University Naoki MURAKAMI, Nihon University Kazuko GOTO, Setsunan University Masatoshi KOJIMA, Toyo University Hideaki MURASE, Gakushuin University Hiroshi KOJIMA, Waseda University Katsumi KOJIMA, Bunkyo University Directors of the Union President Kenichi ENATSU, Waseda University Fumihiko HIRUMA, Waseda University Tetsuji OKAZAKI, University of Tokyo Koji ISHIUCHI, Japan University of Economics Kappei HIDAKA, Chuo University Mitsuhiko TSURUTA, Chuo University Yasuhiro OGURA, Toyo University Katsuaki ONISHI, Senshu University Yoshiaki TAKAHASHI, Chuo University Takahide KOSAKA, Nihon University Secretary General Masataka OTA, Waseda University Auditor Haruhito TAKEDA, University of Tokyo Hideki YOSHIOKA, Takasaki University of Commerce Emeritus Yasuo OKAMOTO, University of Tokyo Osamu NISHIZAWA, Waseda University Toshio KIKUCHI, Nihon University THE UNION OF NATIONAL ECONOMIC ASSOCIATIONS IN JAPAN 日本経済学会連合 The Union of National Economic Associations in Japan, established in 1950, celebrated its 60th anniversary in 2010, as the sole nationwide federation of associations of scholars and experts on economics, commerce, and business administration. -

1. Japanese National, Public Or Private Universities

1. Japanese National, Public or Private Universities National Universities Hokkaido University Hokkaido University of Education Muroran Institute of Technology Otaru University of Commerce Obihiro University of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine Kitami Institute of Technology Hirosaki University Iwate University Tohoku University Miyagi University of Education Akita University Yamagata University Fukushima University Ibaraki University Utsunomiya University Gunma University Saitama University Chiba University The University of Tokyo Tokyo Medical and Dental University Tokyo University of Foreign Studies Tokyo Geijutsu Daigaku (Tokyo University of the Arts) Tokyo Institute of Technology Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology Ochanomizu University Tokyo Gakugei University Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology The University of Electro-Communications Hitotsubashi University Yokohama National University Niigata University University of Toyama Kanazawa University University of Fukui University of Yamanashi Shinshu University Gifu University Shizuoka University Nagoya University Nagoya Institute of Technology Aichi University of Education Mie University Shiga University Kyoto University Kyoto University of Education Kyoto Institute of Technology Osaka University Osaka Kyoiku University Kobe University Nara University of Education Nara Women's University Wakayama University Tottori University Shimane University Okayama University Hiroshima University Yamaguchi University The University of Tokushima Kagawa University Ehime -

12. International Law and Organizations

Developments in 2014 ̶ Academic Societies 165 Yu Hasumi( Professor, Rissho University) (5) “International and European Responses to the Annexation of Crimea by Russia from the perspective of international law” Kyoji Kawasak(i Professor, Hitotsubashi University) (6) Discussion Ichiyo Ishikawa( NHK) Yu Koizumi( Institute for Future Engineering) 12. International Law and Organizations The Japanese Society of International Law held its 2014 Annual Meeting at Toki Messe Niigata Convention Center during September 19-21, 2014. Day One: Plenary Session: <The Honorable Shigeru Oda Commemorative Lectures> ICJ Judgment on Whaling in the Antarctic: Its Significance and Implications Chair: Naoya Okuwaki, Professor, Meiji University 1. The Legal Nature of Resolutions of Intergovernmental Organizations: The Contribution of the Whaling in the Antarctic Case Erik Franckx, Professor, Free University of Brussels 2. ICRW as an Evolving Instrument: Potential Broader Implications of the Whaling Judgment Akiho Shibata, Professor, Kobe University 3. Procedural Questions in the Whaling Judgment: Admissibility, Intervention and Use of Experts Shotaro Hamamoto, Professor, Kyoto University Day Two: Plenary Session: Reaction of Japan to Provisions concerning the “Crime of Aggression” in the International Criminal Court, Part I Chair: Shuichi Furuya, Professor, Waseda University 166 Waseda Bulletin of Comparative Law Vol. 34 1. Kampara Amendments to the Rome Statute concerning the Crime of Aggression: Introduction of the Requirements of Consent and the Negative Understanding of Universalism Akira Mayama, Professor, Osaka University 2. War as a Crime: Politics of the Outbreak, Hostilities and End of a War Atsushi Ishida, Professor, University of Tokyo 3. Germany and the Crime of Aggression Claus Kress, Professor, University of Cologne Group Session 1: Reaction of Japan to Provisions concerning the “Crime of Aggression” in the International Criminal Court, Part II Chair: Masahiko Asada, Professor, Kyoto University 1. -

Read More About the Dharma Drum Lineage of Chan Buddhism

The Dharma Drum Lineage of Chan Buddhism Inheriting the Past and Inspiring the Future Master Sheng Yen CONTENTS Introduction 07 My Commitment and Life’s Mission 11 Inheriting the Past and Inspiring the Future 27 The Dharma Drum Lineage of Chan Buddhism 89 About the Author : Master Sheng Yen 91 Appendix CONTENTS 3 Introduction his booklet is a compilation of six discourses delivered Tby Master Sheng Yen over a two-year period to his monastic Sangha at Dharma Drum Mountain in Taiwan. They have been collected and published here because of their historical importance. They include the Master’s vision of the mission of Dharma Drum, and clarify the origin, purpose, and aim of his newly established Dharma Drum Lineage of Chan Buddhism. Four recorded talks appear in this booklet in their en- tirety; these were delivered on September 23 and 24, and October 7 and 21, 2004. Excerpts from two additional dis- courses were added to form this booklet. The first appears here as “My Commitment and Life’s Mission,” from a talk given in the latter part of April, 2006; the second appears as “Inheriting the Past and Inspiring the Future,” and it comes from a talk given at a retreat at Dharma Drum Mountain on February 21, 2006. Introduction 5 Three monastic disciples, Guo Che, Guo Jian, and Chang Yan, edited this booklet in July, 2006 in Chinese. Mr. Wee Keat Ng prepared the initial English translation. Guo Gu edited, retranslated and added the footnotes, which version was edited in English by Harry Miller and David Berman. -

In Search of Common Icons for the East Asian Union

Ateneo de Manila University Archīum Ateneo Sociology & Anthropology Department Faculty Publications Sociology & Anthropology Department 2007 In Search of Common Icons for the East Asian Union Fernando N. Zialcita Follow this and additional works at: https://archium.ateneo.edu/sa-faculty-pubs Part of the Sociology Commons C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Towards an East Asia Community: Beyond Cross-Cultural Diversity Inter-cultural, Inter-societal, Inter-faith Dialogue December 10 – 18, 2007 Edited by Yasushi Kikuchi The Japan Foundation Ministry of Foreign Aairs of Japan Waseda University Institute of Asia-Pacic Studies Towards an East Asia Community: Beyond Cross-Cultural Diversity Inter-cultural, Inter-societal, Inter-faith Dialogue Published by The Japan Foundation Date of publication June 2008 ©The Japan Foundation 2008 4-4-1 Yotsuya, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, Japan 160-0004 Tel: +81-3-5369-6051 Fax: +81-3-5369-6031 URL: www.jpf.go.jp/e/ Layout & design faro inc. Editorial assistant Motomichi Hiwatashi Photographs Atsuko Takagi (pp12-17, 106-107, 114-197) ISBN: 978-4-87540-096-7 Printed in Japan Contents Preface 6 Overview 7 Part 1: Public Symposium Profiles of Coordinators and Keynote Speaker 11 Profiles of Coordinators 12 Profile of Speaker 17 Presentation Papers 19 Trade, Community and Security in East Asia 20 WANG, Gungwu A Vision towards the East Asia Union: Possible or not? —Social Anthropological Aspect— 29 Yasushi KIKUCHI Harmonizing Strategic Interests and Cross-Cultural Diversity: Requisite for Building an East Asian Community 44 Wilfrido