Revisiting Nichiren Editors,Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guest Editorial

Guest Editorial The issues (Vol.21, No.2 and Vol.21, No.4) of the Journal of Arid Land Studies contain the Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Arid Land (Desert Technology X), held on May 24 - 27 at Hotel Toyoko-Inn Narita Kuko in Narita and held on May 28 at Tokyo University of Agriculture in Tokyo, Japan. The papers presented at the Conference and published in these Proceedings are divided into 10 categories; (1) Controlling the Alien Invasive Species (2) Soil Management (3) Valorization of BioResources (4) Vegetation (5) Hydrology (6) Food Production (7) Desertification and Meteorology (8) Water Management and Energy (9) Arid Land Water Cycle (10) Culture and Life Within each session, a broad diversity of scientific researches, innovative technologies, new applications of technologies and important social perspectives were presented. This reflects the multi-disciplinary approach that will be required to address the challenges toward sustainable management of desert, arid and semiarid regions. The current issue (Vol.21, No.2) contains the proceedings of the Keynote Lectures and Joint International Symposium with JAALS. The draft manuscripts of papers were reviewed by two anonymous reviewers after Conference, except the memorial papers for Prof. Kobori. Revised versions of the papers were then resubmitted. If the manuscripts were revised satisfactorily, they were accepted for publication. The Conference Editorial Panel acknowledges the vital contributions of the following reviewers; List of Reviewers Yukuo ABE, University of Tsukuba, Japan, Majed ABU-ZREIG, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Jordan Ould Ahmed BOUYA AHMED, Institute of Superior Education and Technologies, Mauritania Mingyang DU, National Institute for Agro-Environmental Sciences, Japan Yasuyuki EGASHIRA, Osaka University, Japan Hany A. -

The Saddharmapundarika and Its Influence

THE SADDHARMAPUNDARIKA AND ITS INFLUENCE By Senchu Murano The following paper is a summary of Hokekyo no Shiso to Bunka, edited by Yukio Sakamoto, Dean of the Faculty of Buddhism at Rissho University,Tokyo. (Kyoto,Heirakuji-shoten,1965; 711 pp., Index 31 pp.; Yen 4,000.) PA RT I : THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF THE SADDHARMAPUNDARIKA Chapter L The Formation of the Saddharmapunda?'lka A. The Saddharmapundarika and Indian Culture ( Ensho K anakura) H. Kern holds that the character of the Saddharmapundarika is similar to that of Narayana in the Bhagavadglta and that the Bhagavadglta had great influence on the Saddharmapun darika. Winternitz points out the influence of the Purdnas on the stitra, and Farquhar thinks that the Vedantas influenced the sutra. Kern shows us the materials for his opinion, but W inter nitz and Farquhar do not. On the other hand,Charles Eliot and H. von Glasenapp do speak of the influences of other religions on this sutra. They try to find the sources of the philosophy of the Saddharma pundarika in the current thought of India of the time. This is more convincing. It seems to be true to some extent that the Saddharmapun- — 315 — Senchu Murano dartka was influenced by the Bhagavadglta. It is also true, however, that the monotheistic idea given in the Bhagavadglta was already apparent in the Svetasvatara Upanisad, and that monotheism prevailed in India for some centuries around the beginning of the Christian Era. W e can say that the Saddhar- mapundarlka^ the Bhagavadglta, and other pieces of literature of a similar nature were produced from the common ground of the same age. -

Placing Nichiren in the “Big Picture” Some Ongoing Issues in Scholarship

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1999 26/3-4 Placing Nichiren in the “Big Picture” Some Ongoing Issues in Scholarship Jacqueline I. Stone This article places Nichiren within the context of three larger scholarly issues: definitions of the new Buddhist movements of the Kamakura period; the reception of the Tendai discourse of original enlightenment (hongaku) among the new Buddhist movements; and new attempts, emerging in the medieval period, to locate “Japan ” in the cosmos and in history. It shows how Nicmren has been represented as either politically conservative or rad ical, marginal to the new Buddhism or its paradigmatic figv/re, depending' upon which model of “Kamakura new Buddhism” is employed. It also shows how the question of Nichiren,s appropriation of original enlighten ment thought has been influenced by models of Kamakura Buddnism emphasizing the polarity between “old” and “new,institutions and sug gests a different approach. Lastly, it surveys some aspects of Nichiren ys thinking- about “Japan ” for the light they shed on larger, emergent medieval discourses of Japan relioiocosmic significance, an issue that cuts across the “old Buddhism,,/ “new Buddhism ” divide. Keywords: Nichiren — Tendai — original enlightenment — Kamakura Buddhism — medieval Japan — shinkoku For this issue I was asked to write an overview of recent scholarship on Nichiren. A comprehensive overview would exceed the scope of one article. To provide some focus and also adumbrate the signifi cance of Nichiren studies to the broader field oi Japanese religions, I have chosen to consider Nichiren in the contexts of three larger areas of modern scholarly inquiry: “Kamakura new Buddhism,” its relation to Tendai original enlightenment thought, and new relisdocosmoloei- cal concepts of “Japan” that emerged in the medieval period. -

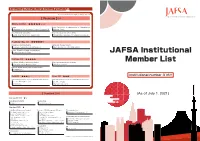

JAFSA Institutional Member List

Supporting Member(Social Business Partners) 43 ※ Classified by the company's major service [ Premium ](14) Diamond( 4) ★★★★★☆☆ Finance Medical Certificate for Visa Immunization for Studying Abroad Western Union Business Solutions Japan K.K. Hibiya Clinic Global Student Accommodation University management and consulting GSA Star Asia K.K. (Uninest) Waseda University Academic Solutions Corporation Platinum‐Exe( 3) ★★★★★☆ Marketing to American students International Students Support Takuyo Corporation (Lighthouse) Mori Kosan Co., Ltd. (WA.SA.Bi.) Vaccine, Document and Exam for study abroad Tokyo Business Clinic JAFSA Institutional Platinum( 3) ★★★★★ Vaccination & Medical Certificate for Student University management and consulting Member List Shinagawa East Medical Clinic KEI Advanced, Inc. PROGOS - English Speaking Test for Global Leaders PROGOS Inc. Gold( 2) ★★★☆ Silver( 2) ★★★ Institutional number 316!! Global Human Resources services・Study Abroad Information Global Human Resources services・Study Abroad Information Access Nextage Co.,Ltd Doorkel Co.,Ltd. DISCO Inc. Mynavi Corporation [ Standard ](29) (As of July 1, 2021) Standard20( 2) ★☆ Study Abroad Information Housing・Hotel Keibunsha MiniMini Corporation . Standard( 27) ★ Study Abroad Program and Support Insurance / Risk Management /Finance Telecommunication Arc Three International Co. Ltd. Daikou Insurance Agency Kanematsu Communications LTD. Australia Ryugaku Centre E-CALLS Inc. Berkeley House Language Center JAPAN IR&C Corporation Global Human Resources Development Fuyo Educations Co., Ltd. JI Accident & Fire Insurance Co., Ltd. JTB Corp. TIP JAPAN Fourth Valley Concierge Corporation KEIO TRAVEL AGENCY Co.,Ltd. Tokio Marine & Nichido Fire Insurance Co., Ltd. Originator Co.,Ltd. OKC Co., Ltd. Tokio Marine & Nichido Medical Service Co.,Ltd. WORKS Japan, Inc. Ryugaku Journal Inc. Sanki Travel Service Co.,Ltd. Housing・Hotel UK London Study Abroad Support Office / TSA Ltd. -

HORIUCHI, Kenji

CURRICULUM VITAE Kenji HORIUCHI University of Shizuoka, Associate Professor Faculty of International Relations, Department of Languages and Cultures (Asian culture course) Graduate School of International Relations Email: [email protected] Address: 52-1 Yada, Suruga-ku, Shizuoka-Shi, 422-8526 JAPAN Education 2006.2 Doctor of Philosophy in Social Sciences, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan 1998.3 Master of Arts in Social Sciences, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan 1991.3 Bachelor of Arts in Literature, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan Employment 2016.4- Associate Professor, School of International Relations, University of Shizuoka 2014.4- Adjunct Researcher, Organization for Regional and Inter-regional Studies, Waseda University 2014.4- Part-time lecturer, Graduate School of Political Science, Kokushikan University 2013.4-2016.3 Part-time lecturer, Komazawa University 2013.4-2015.3 Part-time lecturer, College of Commerce, Nihon University 2011.4-2012.3 Junior researcher, Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies (Assistant Professor at Global-COE Program), Waseda University. 2010.4-2011.3 Adjunct researcher, Overseas Legislative Information Division, Research and Legislative Reference Bureau, National Diet Library 2007.4-2010.3 Assistant Professor, School of Social Sciences, Waseda University 2007.4-2016.3 Part-time lecturer, Rissho University 2003.1-2007.3 Research Associate, Graduate School of Political Science (COE researcher at COE Program), Waseda University 2000.4-2002.3 Research Associate, School of Social Sciences, Waseda University Field of research Central-local relations, regional policy and local politics in Russia (Russian Far East); International Relations in Northeast Asia; Energy Diplomacy Publications (Books) K. Horiuchi, D. Saito and T. Hamano eds., Roshia kyokuto handobukku [Handbook of the Russian Far East], Tokyo: Toyo Shoten, August 2012 (in Japanese). -

¬¬Journal of Buddhist Ethics

ISSN: 1500-0713 ______________________________________________________________ Article Title: How Many Bodies Does It Take to Make a Buddha? Dividing the Trikāya among Founders of Japanese Buddhism Author(s): Victor Forte Source:Japanese Studies Review, Vol. XXIV (2020), pp. 35-60 Stable URL: https://asian.fiu.edu/projects-and-grants/japan- studies-review/journal-archive/volume-xxiv-2020/forte-victor- how-many-bodies.pdf ______________________________________________________________ HOW MANY BODIES DOES IT TAKE TO MAKE A BUDDHA? DIVIDING THE TRIKĀYA AMONG FOUNDERS OF JAPANESE BUDDHISM Victor Forte Albright College Introduction Much of modern scholarship concerned with the historical emer- gence of sectarianism in medieval Japanese Buddhism has sought to deline- ate the key features of philosophy and praxis instituted by founders in order to illuminate critical differences between each movement. One of the most influential early proposed delineations was “single practice theory,” ikkō senju riron 一向専修理論 originating from Japanese scholars like Jikō Hazama 慈弘硲 and Yoshiro Tamura 芳朗田村.1 This argument focused on the founders of the new Kamakura schools during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries like Hōnen 法然, Shinran 親鸞, Dōgen 道元, and Nichiren 日蓮, claiming that each promoted a single Buddhist practice for the attainment of liberation at the exclusion of all other rival practices. In recent scholarship, however, single practice theory has been brought into question.2 As an alternative method of delineation, this study proposes the examination of how three major premod- ern Japanese founders (Kūkai 空海, Shinran, and Dōgen) employed the late Indian Mahāyāna notion of the three bodies of the Buddha (Skt. trikāya, Jp. sanshin 三身) by appropriating a single body of the Buddha in order to distin- guish each of their sectarian movements. -

Application Guidelines for Rissho University Student Exchange Program 2019 Spring

Application Guidelines for Rissho University Student Exchange Program 2019 Spring Rissho University accepts short-term international exchange students from partner universities / institutions abroad (within one year in principle). This program enables exchange students to take classes at each Faculty of Rissho University. All classes are conducted in Japanese. Exchange students will be given the chance to interact with the students and staff of Rissho University and deepen their understanding of Japan and become active individuals in today's international society. 1. Qualifications for Applicants Applicants must meet all of the following requirements. (1) Is a registered student at a partner university / institution of Rissho University (2) Is a student who is required to earn credits at Rissho University (3) Is able to submit one or more of the following documents to verify Japanese proficiency. a) Certificate of EJU (Examination for Japanese University Admission for International Students) with the score of 220 or higher on "Japanese as a Foreign Language" b) Certificate of JLPT (Japanese Language Proficiency Test) "Level N1" with the score of 145 or higher * Please consult us if the student is not able to demonstrate their Japanese language skills by providing their EJU or JLPT results but has the equal language ability. * If the student's Japanese language proficiency does not meet the above requirements, they are able to take the Japanese Language Program course (please refer to the Application Guidelines for Rissho University Japanese-Language Program Semester Course). 2. Requirements for taking classes available at each faculty Faculty of Buddhist Studies Must have basic knowledge of Buddhist Studies or Nichiren Buddhism. -

Download a PDF Copy of the Guide to Jodo Shinshu Teachings And

Adapted from: Renken Tokuhon Study Group Text for Followers of Shinran Shonin By: Kyojo S. Ikuta Guide & Trudy Gahlinger to June 2008 Jodo Shinshu Teachings and Practices INTRODUCTION This Guide to Jodo Shinshu Teachings and Practices is a translation of the Renken Tokuhon Study Group Text for Followers of Shinran Shonin. TheGuide has been translated from the original version in Japanese and adapted for Jodo Shinshu Temples in North America. TheGuide has been developed as an introduction to Jodo Shinshu for the layperson. It is presented in 2 parts. Part One describes the life and teachings of the Buddha, and the history and evolution of Jodo Shinshu teachings. Part Two discusses Jodo Shinshu practices, including Jodo Shinshu religious days and services. The Calgary Buddhist Temple gratefully acknowledges the Renken Tokuhon Study Group for providing the original text, and our mother Temple in Kyoto - the Jodo Shinshu Hongwanji-ha - for supporting our efforts. It is our hope that this Guide will provide a basic foundation for understanding Jodo Shinshu, and a path for embracing the life of a nembutsu follower. Guide to Jodo Shinshu Teachings and Practices Table of Contents PART ONE: JODO SHINSHU TEACHINGS 1 THE LIFE OF THE BUDDHA . 2 1.1 Birth of the Buddha . 2 1.2 Renunciation . 2 1.3 Practice and Enlightenment . 2 1.4 First Sermon . 2 1.5 Propagation of the Teachings and the Sangha . 3 1.6 The Buddha’s Parinirvana . 3 1.7 The First Council . 4 2 SHAKYAMUNI’S TEACHINGS. 5 2.1 Dependent Origination (Pratitya-Samutpada) . 5 2.2 The Four Marks of Dharma. -

Time and Self: Religious Awakening in Dogen and Shinran

Time and Self: Religious Awakening in Dogen and Shinran TRENT COLLIER [The nembutsu] is precisely for those who are utterly ignorant and foolish, and who therefore forget about study and practice, believing that simply to say the Name of Amida Buddha with their tongues, day and night, is to enact the fulfillment of practice. While the way of wisdom corr nds to the Tendai teaching or Zen meditation, the gate of compassion designed for the foolish does not differ with regard to what is true and real. On a cold night, it makes no difference whether you are wearing robes of pat terned brocade or lying under layers of hempen patchwork once you have fallen asleep and forgotten about the wind. Shinkei N this passage from a 15th century work on renga poetry, Shinkei (1406-1475) contrasts the arduous path of Tendai or Zen with the com parativelyI simple path of nembutsu practice.1 While Shinkei was speaking figuratively, the literal meaning of his words—that the nembutsu is for the “foolish and ignorant”—reflects a perception of the Pure Land path that per sists to this day. Buddhist studies in the modem West have largely ignored the Pure Land tradition, focusing instead on schools that are more obviously complex, philosophical, or meditative. Whether from disinterest in the doc trines and practices of the Pure Land tradition or from aversion to traditions too similar in structure to the Judeo-Christian tradition, Western students of Buddhism have neglected a large and thoroughly profound body of work. 1 Dennis Hirota, Wind in the Pines: Classic Writings o f the Way o f Tea as a Buddhist Path (Fremont, California: Asian Humanities Press, 1995), 168—9. -

Creating Heresy: (Mis)Representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-Ryū

Creating Heresy: (Mis)representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-ryū Takuya Hino Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Takuya Hino All rights reserved ABSTRACT Creating Heresy: (Mis)representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-ryū Takuya Hino In this dissertation I provide a detailed analysis of the role played by the Tachikawa-ryū in the development of Japanese esoteric Buddhist doctrine during the medieval period (900-1200). In doing so, I seek to challenge currently held, inaccurate views of the role played by this tradition in the history of Japanese esoteric Buddhism and Japanese religion more generally. The Tachikawa-ryū, which has yet to receive sustained attention in English-language scholarship, began in the twelfth century and later came to be denounced as heretical by mainstream Buddhist institutions. The project will be divided into four sections: three of these will each focus on a different chronological stage in the development of the Tachikawa-ryū, while the introduction will address the portrayal of this tradition in twentieth-century scholarship. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations……………………………………………………………………………...ii Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………iii Dedication……………………………………………………………………………….………..vi Preface…………………………………………………………………………………………...vii Introduction………………………………………………………………………….…………….1 Chapter 1: Genealogy of a Divination Transmission……………………………………….……40 Chapter -

"Shinran's Rejection of Deathbed Rites" (2012)

pear directly as quotations in Shinran.'s writings, but surely his intent is that they be preserved and read. Shinran's Rejection of Deathbed Rites 6) I follow the reading of Imai Masaharu, who has pointed out that the verb forms employed by Eshinni indicate that she directly witnessed these encounters and sug , gests that she herself had already been a member of H6nen's following at the time. See Imai Masaharu. Shim-an to Eshinni. (Kyoto: ]ish6 Shuppan, 2004). Jacqueline I. Stone 7) In Adriaan T. Peperzak, Simon Critchley, and Robert Bernascont eds., Emmanuel · Levinas: Basic Philosophical Writings, (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana Uni versity Press.l996), p. 104. In 1259 and 1260. famine and disease devastated Japan's eastern provinces. 8) There is a slight difference between Shinran's quotation and the most widespread Shinran (1173-1262)-later revered as the founder of Jodo ShinshU. or the version of H6nen's text, representing perhaps some authorial variation in choice True Pure Land sect-wrote to his follower Joshin-bo expressing sorrow among synonyms. The common text has "foremost'' (saki, )'G) and Shinran's copy that so many people, old and young, had died. Then he added, "Personally, I has ~fundamental" (hon, /.j.l:). Although basically indistingujshable in meaning. Shin attach no significance to the manner of one's death, good or bad. Those in ran's hon is appropriate to the central meaning he emphasizes in HOnen's expres whom faith is established have no doubts; therefore they dwell in the com sion. pany of those certain to be born in the Pure Land (shajoju). -

From Inspiration to Institution the Rise of Sectarian Identity in Jōdo Shinshū

From Inspiration to Institution The Rise of Sectarian Identity in Jōdo Shinshū James C. Dobbins When tracing their origins, religious organizations often depict themselves as springing into existence full-bodied from the inspiration of a founder.* Whatever they may claim as their starting point—revelation, enlightenment experience, charismatic leader, or what not—they consider institutional forms to be a direct extension and an immediate and inevitable result of that inspired beginning. Hence sectarian histories draw institutional conclusions from for- mative visions, and emphasize the community of believers and the religious network that coalesce around that inspiration. The rise of religious organizations, however, is generally more protracted and complicated than this. It entails an elaborate and extended evolution wherein belief systems, ceremonies and ritual, hierarchies, legitimation of au- thority, and institutional structure are all gradually defined. The end result is a complex constellation of religious forms that are only intimated, if included at all, in the original vision of the founder. Nonetheless, that vision functions as a causal force and sets in motion the entire evolutionary chain; it provides the raw material from which subsequent interpretations are fashioned, so that what arises later does indeed have a link to what has gone before. The intri- cate process of sectarian evolution is well exemplified in the history of Jōdo Shinshū 浄土真宗, one of the largest schools of Buddhism in Japan. Jōdo Shinshū, known more simply as Shinshū, emerged out of the teach- ings of Shinran 親鸞, 1173–1262, and from the band of followers he left behind. Shinran did not consider himself the founder of a school of Buddhism, nor was his following clearly distinguishable from the broader Pure Land move- ment originated by his teacher Hōnen 法然, 1133–1212.