In Search of Common Icons for the East Asian Union

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strings Revolution: Shamisen Handout

NCTA Mini Course June 11, 2020 Yuko Eguchi Wright Ph.D. East Asian Languages and Literatures University of Pittsburgh [email protected] / www.yukoeguchi.com Strings Revolution: History and Music of Shamisen and Geisha Resources Shamisen Film: Kubo and the Two Strings (2016) OCLC: 1155092874 General Info: Marusan Hashimoto Co. http://www.marusan-hashimoto.com/english/ Making and Buying Shamisen: Tokyo Teshigoto https://tokyoteshigoto.tokyo/en/kikuokaws Sangenshi Kikuoka — “Kojyami Chinton Kit” https://www.syokuninkai.com/products/detail.php?product_id=463 (in Japanese) Bachido USA https://bachido.com Sasaya (my shamisen store) Mr. Shinozaki in Sugamo, Tokyo, Tel: 03-3941-6323 (in Japanese) Books: Henry Johnson, The Shamisen, Brill (2010) Gerald Groemer, The Sprit of Tsugaru, Harmonie Park (1999) William Malm, Traditional Japanese Music and Musical Instruments, Kōdansha Int. (2000) Geisha Film and Documentary: A Geisha (1953) by Mizoguchi Kenji OCLC: 785846930 NHK Documentary “A Tale of Love and Honor: Life in Gion” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A3MlHPpYlXE&feature=youtu.be BBC Documentary “Geisha Girl” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gWSEQGZgj_s&feature=youtu.be 1 / 3 NCTA Mini Course June 11, 2020 Books: Peabody Essex Museum, Geisha: Beyond the Painted Smile (2004) Liza Dalby, Geisha, Vintage (1985) Liza Dalby, Little Songs of the Geisha, Tuttle (2000) Kelly Foreman, The Gei of Geisha, Ashgate (2008) Iwasaki Mineko, Geisha, A Life, Atria (2002) John Foster, Geisha & Maiko of Kyoto, Schiffer (2009) Japanese Music and Arts Begin Japanology and Japanology Plus (NHK TV series hosted by Peter Barakan) Main Website: https://www3.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld/en/ondemand/program/video/japanologyplus/?type=tvEpisode& Shamisen: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KizZ09vogBY Bunraku: https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x7kylch Kabuki: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CbYRaKilD1M Geisha: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZzevWcTwCZY 2 / 3 NCTA Mini Course June 11, 2020 Quiz What are these Japanese instruments called? selections: 1- kotsuzumi, 2 - shamisen, 3 - fue, 4 - taiko, 5 - ōtsuzumi A. -

Guest Editorial

Guest Editorial The issues (Vol.21, No.2 and Vol.21, No.4) of the Journal of Arid Land Studies contain the Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Arid Land (Desert Technology X), held on May 24 - 27 at Hotel Toyoko-Inn Narita Kuko in Narita and held on May 28 at Tokyo University of Agriculture in Tokyo, Japan. The papers presented at the Conference and published in these Proceedings are divided into 10 categories; (1) Controlling the Alien Invasive Species (2) Soil Management (3) Valorization of BioResources (4) Vegetation (5) Hydrology (6) Food Production (7) Desertification and Meteorology (8) Water Management and Energy (9) Arid Land Water Cycle (10) Culture and Life Within each session, a broad diversity of scientific researches, innovative technologies, new applications of technologies and important social perspectives were presented. This reflects the multi-disciplinary approach that will be required to address the challenges toward sustainable management of desert, arid and semiarid regions. The current issue (Vol.21, No.2) contains the proceedings of the Keynote Lectures and Joint International Symposium with JAALS. The draft manuscripts of papers were reviewed by two anonymous reviewers after Conference, except the memorial papers for Prof. Kobori. Revised versions of the papers were then resubmitted. If the manuscripts were revised satisfactorily, they were accepted for publication. The Conference Editorial Panel acknowledges the vital contributions of the following reviewers; List of Reviewers Yukuo ABE, University of Tsukuba, Japan, Majed ABU-ZREIG, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Jordan Ould Ahmed BOUYA AHMED, Institute of Superior Education and Technologies, Mauritania Mingyang DU, National Institute for Agro-Environmental Sciences, Japan Yasuyuki EGASHIRA, Osaka University, Japan Hany A. -

The Saddharmapundarika and Its Influence

THE SADDHARMAPUNDARIKA AND ITS INFLUENCE By Senchu Murano The following paper is a summary of Hokekyo no Shiso to Bunka, edited by Yukio Sakamoto, Dean of the Faculty of Buddhism at Rissho University,Tokyo. (Kyoto,Heirakuji-shoten,1965; 711 pp., Index 31 pp.; Yen 4,000.) PA RT I : THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF THE SADDHARMAPUNDARIKA Chapter L The Formation of the Saddharmapunda?'lka A. The Saddharmapundarika and Indian Culture ( Ensho K anakura) H. Kern holds that the character of the Saddharmapundarika is similar to that of Narayana in the Bhagavadglta and that the Bhagavadglta had great influence on the Saddharmapun darika. Winternitz points out the influence of the Purdnas on the stitra, and Farquhar thinks that the Vedantas influenced the sutra. Kern shows us the materials for his opinion, but W inter nitz and Farquhar do not. On the other hand,Charles Eliot and H. von Glasenapp do speak of the influences of other religions on this sutra. They try to find the sources of the philosophy of the Saddharma pundarika in the current thought of India of the time. This is more convincing. It seems to be true to some extent that the Saddharmapun- — 315 — Senchu Murano dartka was influenced by the Bhagavadglta. It is also true, however, that the monotheistic idea given in the Bhagavadglta was already apparent in the Svetasvatara Upanisad, and that monotheism prevailed in India for some centuries around the beginning of the Christian Era. W e can say that the Saddhar- mapundarlka^ the Bhagavadglta, and other pieces of literature of a similar nature were produced from the common ground of the same age. -

CURRICULUM VITAE François Louis Associate Professor, the Bard Graduate Center: Studies in the Decorative Arts, Design, and Culture

CURRICULUM VITAE François Louis Associate Professor, The Bard Graduate Center: Studies in the Decorative Arts, Design, and Culture 18 West 86th Street New York, NY 10024 Phone (office): 212-501-3088 Fax. (office): 212-501-3045 E-mail: [email protected] Nationality: Swiss; U.S. resident alien Languages: German (mother tongue); French; Italian; Chinese; Latin EDUCATION Ph.D. East Asian Art History, University of Zurich (1997) M.phil. European Art History (minors: East Asian Art History and Sinology), University of Zurich (1992) EMPLOYMENT 1999– Bard Graduate Center, New York (Assistant Professor until 2004) 2002–2008 ARTIBUS ASIAE: Editor-in-Chief 1992–1998 Museum Rietberg Zurich: Research Assistant; Assistant Curator; Research Associate 1993–1996 University of Zurich: Lecturer in Art History COURSES OFFERED Bard Graduate Center 500/501. Survey of the Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture 526. Decorative Arts of Later Imperial China, 1100-1900 563. Interiors in Early Modern China and Japan 564. Design and Ritual in Imperial China 567. Art and Material Culture of the Tang Period: Famensi 572. Arts of Song Period China, 960-1279 590. Bard Term Study Abroad: China 598. Master's Thesis Seminar 627. Western Luxuries and Chinese Taste 646. Domestic Interiors in China 648. Art and Ornament in Early China, 1500–1 BCE 694. Landscape and Rusticity in the Chinese Living Environment 702. A Cultural History of Gardens in China and Japan 752. Antiquaries and Antiquarianism in Europe and China, 1000-1800 761. Design and Material Culture of the Qing Period 802. Arts of the Kitan Empire (907-1125) 820. Chinese Ceramics 817. -

NUPACE Academic Policies & Syllabi

NUPACE Academic Policies & Syllabi Autumn 2011 名古屋大学 短期交換留学プログラム . NUPACE Academic Calendar & Policies – Autumn 2011 1. Calendar Oct 3 ~ Jan 27 NUPACE (Japan area studies; majors) & regular university courses Oct 11 ~ Feb 6 University-wide Japanese Language Programme (UWJLP) Jan 30 ~ Feb 10 Examination period for regular university courses Dec 28 ~ Jan 7 Winter vacation for NUPACE & regular university courses Dec 23 ~ Jan 9 Winter vacation for UWJLP programme Apr 12 (tentative) Spring 2012 semester commences National Holidays (No classes will be held on the following days) Oct 10 体育の日 (Health-Sports Day) Nov 3 文化の日 (Culture Day) Nov 23 労働感謝の日 (Labour Thanksgiving Day) Dec 23 天皇誕生日 (Emperor’s Birthday) Jan 9 成人の日 (Coming-of-Age Day) Feb 11 建国記念日 (National Foundation Day) Mar 20 春分の日 (Vernal Equinox Day) 2. List of Courses Open to NUPACE Students Japanese Language Programmes pp 7~10 Standard Course in Japanese (7 Levels: SJ101~SJ301) 1~5 crdts p 8 Intensive Course in Japanese (6 Levels: IJ111~IJ212) 2~10crdts p 9 ビジネス日本語 I, II, III 1 credit p 10 漢字<Kanji>1000, 2000 1 credit p 10 オンライン日本語<Online Japanese>(中上級読解・作文) 0 credits p 10 入門講義 <J>* (ECIS Introductory Courses Taught in Japanese) 国際関係論 I (Global Society I) 2 credits p 10 日本文化論 I (Introduction to Japanese Society & Culture I) 2 credits p 11 日本語学・日本語教育学 I (Introduction to Japanese Linguistics I) 2 credits p 12 言語学入門 I (Introduction to Linguistics I) 2 credits p 12 *<J> Courses which require at least level 2/N2 of the Japanese Language Proficiency Test (JLPT), or equivalent. -

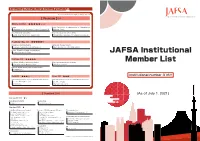

JAFSA Institutional Member List

Supporting Member(Social Business Partners) 43 ※ Classified by the company's major service [ Premium ](14) Diamond( 4) ★★★★★☆☆ Finance Medical Certificate for Visa Immunization for Studying Abroad Western Union Business Solutions Japan K.K. Hibiya Clinic Global Student Accommodation University management and consulting GSA Star Asia K.K. (Uninest) Waseda University Academic Solutions Corporation Platinum‐Exe( 3) ★★★★★☆ Marketing to American students International Students Support Takuyo Corporation (Lighthouse) Mori Kosan Co., Ltd. (WA.SA.Bi.) Vaccine, Document and Exam for study abroad Tokyo Business Clinic JAFSA Institutional Platinum( 3) ★★★★★ Vaccination & Medical Certificate for Student University management and consulting Member List Shinagawa East Medical Clinic KEI Advanced, Inc. PROGOS - English Speaking Test for Global Leaders PROGOS Inc. Gold( 2) ★★★☆ Silver( 2) ★★★ Institutional number 316!! Global Human Resources services・Study Abroad Information Global Human Resources services・Study Abroad Information Access Nextage Co.,Ltd Doorkel Co.,Ltd. DISCO Inc. Mynavi Corporation [ Standard ](29) (As of July 1, 2021) Standard20( 2) ★☆ Study Abroad Information Housing・Hotel Keibunsha MiniMini Corporation . Standard( 27) ★ Study Abroad Program and Support Insurance / Risk Management /Finance Telecommunication Arc Three International Co. Ltd. Daikou Insurance Agency Kanematsu Communications LTD. Australia Ryugaku Centre E-CALLS Inc. Berkeley House Language Center JAPAN IR&C Corporation Global Human Resources Development Fuyo Educations Co., Ltd. JI Accident & Fire Insurance Co., Ltd. JTB Corp. TIP JAPAN Fourth Valley Concierge Corporation KEIO TRAVEL AGENCY Co.,Ltd. Tokio Marine & Nichido Fire Insurance Co., Ltd. Originator Co.,Ltd. OKC Co., Ltd. Tokio Marine & Nichido Medical Service Co.,Ltd. WORKS Japan, Inc. Ryugaku Journal Inc. Sanki Travel Service Co.,Ltd. Housing・Hotel UK London Study Abroad Support Office / TSA Ltd. -

Title My'cro Documentary a Motion Picture Narrative for the Millennials Sub Title Author Sombunjaroen, Armaj(Ota, Naohisa)

Title My'cro documentary a motion picture narrative for the millennials Sub Title Author Sombunjaroen, Armaj(Ota, Naohisa) 太田, 直久 Publisher 慶應義塾大学大学院メディアデザイン研究科 Publication year 2014 Jtitle Abstract Notes 修士学位論文. 2014年度メディアデザイン学 第354号 Genre Thesis or Dissertation URL https://koara.lib.keio.ac.jp/xoonips/modules/xoonips/detail.php?koara_id=KO40001001-0000201 4-0354 慶應義塾大学学術情報リポジトリ(KOARA)に掲載されているコンテンツの著作権は、それぞれの著作者、学会または出版社/発行者に帰属し、その権利は著作権法によって 保護されています。引用にあたっては、著作権法を遵守してご利用ください。 The copyrights of content available on the KeiO Associated Repository of Academic resources (KOARA) belong to the respective authors, academic societies, or publishers/issuers, and these rights are protected by the Japanese Copyright Act. When quoting the content, please follow the Japanese copyright act. Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Master’s Thesis Academic Year 2014 ! ! ! ! ‘My’cro Documentary A Motion Picture Narrative for the Millennials ! ! ! ! Graduate School of Media Design Keio University ! Armaj Sombunjaroen ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A Master’s Thesis submitted to Graduate School of Media Design, Keio University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER of Media Design ! Armaj Sombunjaroen ! Thesis Committee: Professor Naohisa Ohta (Supervisor) Project Senior Assistant Professor Satoru Tokuhisa (Co-Supervisor) Professor Yoko Ishikura (Co-Supervisor) Abstract of Master’s Thesis of Academic Year 2014 ! ‘My’cro Documentary, a Motion Picture Narrative for the Millennials ! Category:! Design Summary! Documentary is the medium used to advocate and to create an awareness for a cause but society is always changing and the narrative of the documentaries’ today has to evolve with the time. This design thesis explores a different perspective to the world of documentary making with a concept called ‘My’cro documentary. -

HORIUCHI, Kenji

CURRICULUM VITAE Kenji HORIUCHI University of Shizuoka, Associate Professor Faculty of International Relations, Department of Languages and Cultures (Asian culture course) Graduate School of International Relations Email: [email protected] Address: 52-1 Yada, Suruga-ku, Shizuoka-Shi, 422-8526 JAPAN Education 2006.2 Doctor of Philosophy in Social Sciences, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan 1998.3 Master of Arts in Social Sciences, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan 1991.3 Bachelor of Arts in Literature, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan Employment 2016.4- Associate Professor, School of International Relations, University of Shizuoka 2014.4- Adjunct Researcher, Organization for Regional and Inter-regional Studies, Waseda University 2014.4- Part-time lecturer, Graduate School of Political Science, Kokushikan University 2013.4-2016.3 Part-time lecturer, Komazawa University 2013.4-2015.3 Part-time lecturer, College of Commerce, Nihon University 2011.4-2012.3 Junior researcher, Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies (Assistant Professor at Global-COE Program), Waseda University. 2010.4-2011.3 Adjunct researcher, Overseas Legislative Information Division, Research and Legislative Reference Bureau, National Diet Library 2007.4-2010.3 Assistant Professor, School of Social Sciences, Waseda University 2007.4-2016.3 Part-time lecturer, Rissho University 2003.1-2007.3 Research Associate, Graduate School of Political Science (COE researcher at COE Program), Waseda University 2000.4-2002.3 Research Associate, School of Social Sciences, Waseda University Field of research Central-local relations, regional policy and local politics in Russia (Russian Far East); International Relations in Northeast Asia; Energy Diplomacy Publications (Books) K. Horiuchi, D. Saito and T. Hamano eds., Roshia kyokuto handobukku [Handbook of the Russian Far East], Tokyo: Toyo Shoten, August 2012 (in Japanese). -

HA 362/562 CERAMIC ARTS of KOREA – PLACENTA JARS, POTTERY WARS and TEA CULTURE Maya Stiller University of Kansas

HA 362/562 CERAMIC ARTS OF KOREA – PLACENTA JARS, POTTERY WARS AND TEA CULTURE Maya Stiller University of Kansas COURSE DESCRIPTION From ancient to modern times, people living on the Korean peninsula have used ceramics as utensils for storage and cooking, as well as for protection, decoration, and ritual performances. In this class, students will examine how the availability of appropriate materials, knowledge of production/firing technologies, consumer needs and intercultural relations affected the production of different types of ceramics such as Koryŏ celadon, Punch’ŏng stoneware, ceramics for the Japanese tea ceremony, blue-and-white porcelain, and Onggi ware (a specific type of earthenware made for the storage of Kimch’i and soybean paste). The class has two principal goals. The first is to develop visual analysis skills and critical vocabulary to discuss the material, style, and decoration techniques of Korean ceramics. By studying and comparing different types of ceramics, students will discover that ceramic traditions are an integral part of any society’s culture, and are closely connected with other types of cultural products such as painting, sculpture, lacquer, and metalware. Via an analysis of production methods, students will realize that the creation of a perfect ceramic piece requires the fruitful collaboration of dozens of artisans and extreme attention to detail. The second goal is to apply theoretical frameworks from art history, cultural studies, anthropology, history, and sociology to the analysis of Korean ceramic traditions to develop a deeper, intercultural understanding of their production. Drawing from theoretical works on issues such as the distinction between art and handicraft (Immanuel Kant), social capital (Pierre Bourdieu), “influence” (Michael Baxandall) and James Clifford’s “art-culture system,” students will not only discuss the function of ceramics in mundane and religious space but also explore aspects such as patronage, gender, collecting, and connoisseurship within and outside Korea. -

Burma Project a 080901

Burma / Myanmar Bibliographical Project Siegfried M. Schwertner Bibliographical description AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA A.B.F.M.S. AA The Foundation of Agricultural Development and American Baptist Foreign Mission Society Education Wild orchids in Myanmar : last paradise of wild orchids A.D.B. Tanaka, Yoshitaka Asian Development Bank < Manila > AAF A.F.P.F.L. United States / Army Air Forces Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League Aalto , Pentti A.F.R.A.S.E Bibliography of Sino-Tibetan lanuages Association Française pour le Recherche sur l’Asie du Sud-Est Aanval in Birma / Josep Toutain, ed. – Hilversum: Noo- itgedacht, [19-?]. 64 p. – (Garry ; 26) Ā´´ Gy ū´´ < Pyaw Sa > NL: KITLV(M 1998 A 4873) The tradition of Akha tribe and the history of Akha Baptist in Myanmar … [/ ā´´ Gy ū´´ (Pyaw Sa)]. − [Burma : ākh ā Aaron, J. S. Nhac` khran`´´ Kharac`y ān` A phvai´ khyup`], 2004. 5, 91 Rangoon Baptist Pulpit : the king's favourite ; a sermon de- p., illus. , bibliogr. p. 90-91. − Added title and text in Bur- livered on Sunday morning, the 28th September 1884 in the mese English Baptist Church, Rangoon / by J. S. Aaron. 2nd ed. − Subject(s): Akha : Social life and customs ; Religion Madras: Albinion Pr., 1885. 8 p. Burma : Social life and customs - Akha ; Religion - Akha ; GB: OUL(REG Angus 30.a.34(t)) Baptists - History US: CU(DS528.2.K37 A21 2004) Aarons , Edward Sidney <1916-1975> Assignment, Burma girl : an original gold medal novel / by A.I.D. Edward S. Aarons. – Greenwich, Conn.: Fawcett Publ., United States / Agency for International Development 1961. -

Application Guidelines for Rissho University Student Exchange Program 2019 Spring

Application Guidelines for Rissho University Student Exchange Program 2019 Spring Rissho University accepts short-term international exchange students from partner universities / institutions abroad (within one year in principle). This program enables exchange students to take classes at each Faculty of Rissho University. All classes are conducted in Japanese. Exchange students will be given the chance to interact with the students and staff of Rissho University and deepen their understanding of Japan and become active individuals in today's international society. 1. Qualifications for Applicants Applicants must meet all of the following requirements. (1) Is a registered student at a partner university / institution of Rissho University (2) Is a student who is required to earn credits at Rissho University (3) Is able to submit one or more of the following documents to verify Japanese proficiency. a) Certificate of EJU (Examination for Japanese University Admission for International Students) with the score of 220 or higher on "Japanese as a Foreign Language" b) Certificate of JLPT (Japanese Language Proficiency Test) "Level N1" with the score of 145 or higher * Please consult us if the student is not able to demonstrate their Japanese language skills by providing their EJU or JLPT results but has the equal language ability. * If the student's Japanese language proficiency does not meet the above requirements, they are able to take the Japanese Language Program course (please refer to the Application Guidelines for Rissho University Japanese-Language Program Semester Course). 2. Requirements for taking classes available at each faculty Faculty of Buddhist Studies Must have basic knowledge of Buddhist Studies or Nichiren Buddhism. -

Thomas Donald Conlan 207 JONES HALL, PRINCETON NJ 08544 (609) 258-4773• [email protected] FAX (609) 258-6984

Thomas Donald Conlan 207 JONES HALL, PRINCETON NJ 08544 (609) 258-4773• [email protected] FAX (609) 258-6984 Curriculum Vitae EMPLOYMENT Princeton University: Professor of Medieval Japanese History, Joint Appointment, Department of East Asian Studies and History July 2013-present Bowdoin College: Professor of Japanese History, Joint Appointment, Asian Studies Program and Department of History July 2010-June 2013 Bowdoin College: Associate Professor of Japanese History, Joint Appointment, Asian Studies Program and Department of History July 2004-June 2010 Bowdoin College: Assistant Professor of Japanese History, Joint Appointment, Asian Studies Program and Department of History July 1998-June 2004 EDUCATION Stanford University, Ph.D., History August 1998 Major concentration: Japan before 1600 Minor concentration: Japan since 1600 Kyoto University, Faculty of Letters, Ph.D. Program, History April 1995-September 1997 Stanford University, M.A., History June 1992 The University of Michigan, April 1989 B.A. History and Japanese, with Highest Honors PUBLICATIONS Monographs From Sovereign to Symbol: An Age of Ritual Determinism in Fourteenth Century Japan. New York: Oxford University Press, October 2011. Weapons and the Fighting Techniques of the Samurai Warrior, 1200-1877. New York: Amber Press, August 2008. Translated into Japanese as Zusetsu Sengoku Jidai: Buki Bōgu Senjutsu Hyakka (図説 戦国時代 武器・防具・戦術百科). Tokyo: Hara Shobō 2013. Also translated into French, German, Spanish, Hungarian, Russian and Portuguese. State of War: The Violent Order of Fourteenth-Century Japan. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Center for Japanese Studies, December 2003. In Little Need of Divine Intervention: Takezaki Suenaga’s Scrolls of the Mongol Invasions of Japan. Ithaca: Cornell University East Asia Program, August 2001.