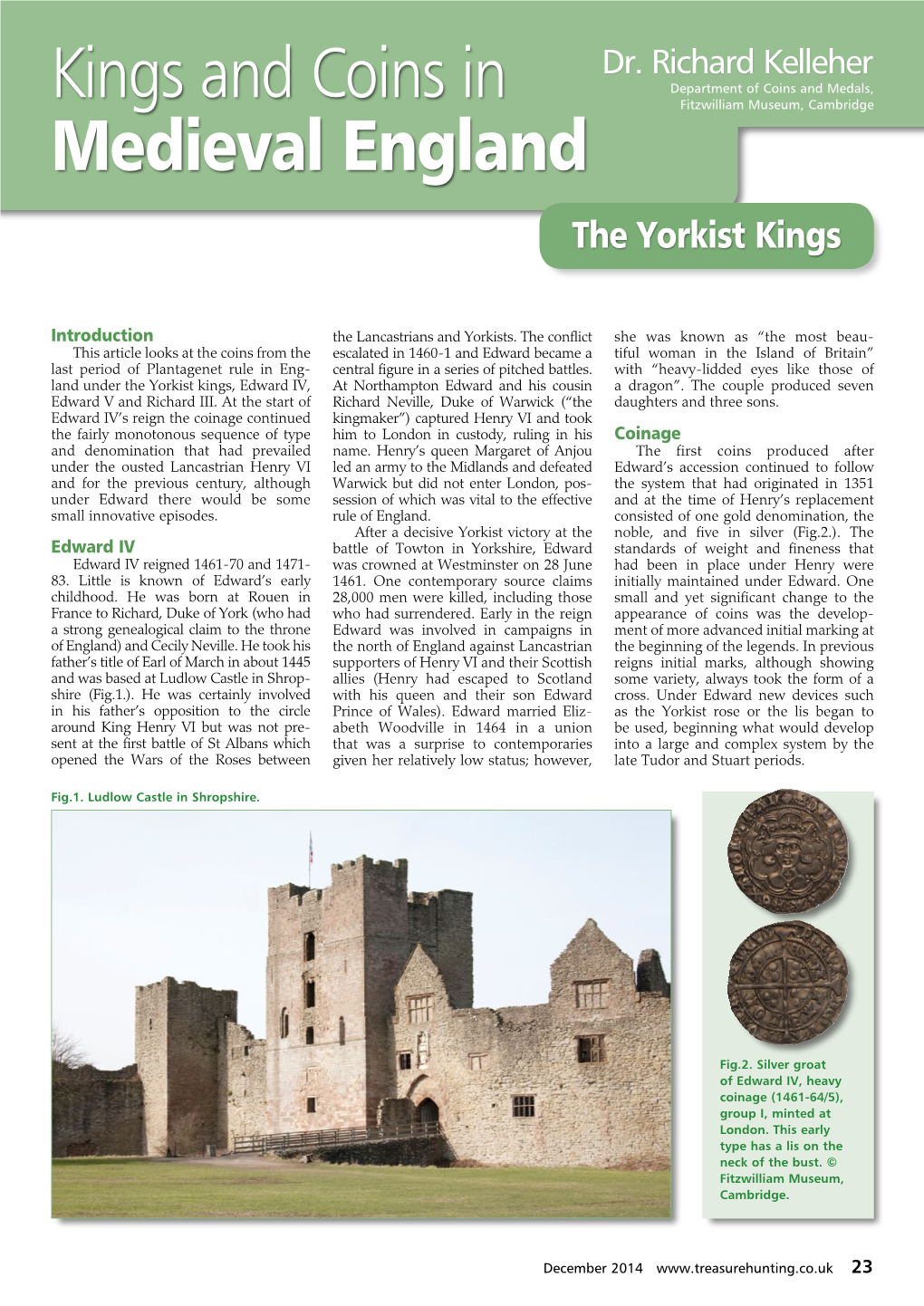

Kings and Coins in Medieval England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cochran-Patrick, RW, Notes on the Scottish

PROCEEDINGS of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland Our full archive of freely accessible articles covering Scottish archaeology and history is available at http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/view/psas/volumes.cfm National Museums Scotland Chambers Street, Edinburgh www.socantscot.org Charity No SC 010440 5 SCOTTISE NOTE22 TH N SO H MINTS. IV. E SCOTTISNOTETH N SO H MINTS. WR . Y COCHRAB . N PATRICK, ESQ., B.A., LL.B., F.S.A. SCOT. Any account which can now be given of the ancient Scottish mints must necessarily he very incomplete. The early records and registers are no longe scantw fe existencen ri ye th notice d an , s gatheree which n hca d fro Acte m th Parliamentf so othed an , r original sources, only serv shoo et w how imperfect our knowledge is. It may not, however, he altogether without interest to hring together something of what is still available, in the hope that other sources of information may yet be discovered. The history of the Scottish mints may be conveniently divided into two periods,—the first extendinge fro th earliese f mo th d ten timee th o st thirteenth century; the second beginning with the fourteenth century, and coming down to the close of the Scottish coinage at the Union. It must he remembered that there is little or no historical evidence availabl firse th tr perioefo d beyond wha s afforde i tcoine th y s b dthem - selvesconclusiony An . scome whicb regardino y et hma o t musgt i e b t a certain extent conjectures e liablmodified authentiy h ,an an o t e y b d c information whic stily e discoveredb lhma t I present. -

Gladstone and the Bank of England: a Study in Mid-Victorian Finance, 1833-1866

GLADSTONE AND THE BANK OF ENGLAND: A STUDY IN MID-VICTORIAN FINANCE, 1833-1866 Patricia Caernarv en-Smith, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Denis Paz, Major Professor Adrian Lewis, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of History Laura Stern, Committee Member Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Caernarven-Smith, Patricia. Gladstone and the Bank of England: A Study in Mid- Victorian Finance, 1833-1866. Master of Arts (History), May 2007, 378 pp., 11 tables, bibliography, 275 titles. The topic of this thesis is the confrontations between William Gladstone and the Bank of England. These confrontations have remained a mystery to authors who noted them, but have generally been ignored by others. This thesis demonstrates that Gladstone’s measures taken against the Bank were reasonable, intelligent, and important for the development of nineteenth-century British government finance. To accomplish this task, this thesis refutes the opinions of three twentieth-century authors who have claimed that many of Gladstone’s measures, as well as his reading, were irrational, ridiculous, and impolitic. My primary sources include the Gladstone Diaries, with special attention to a little-used source, Volume 14, the indexes to the Diaries. The day-to-day Diaries and the indexes show how much Gladstone read about financial matters, and suggest that his actions were based to a large extent upon his reading. In addition, I have used Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates and nineteenth-century periodicals and books on banking and finance to understand the political and economic debates of the time. -

Salvum Fac, and from Their Neatness and Extreme Rarity, Possibly As Patterns

This is a reproduction of a book from the McGill University Library collection. Title: A view of the coinage of Scotland : with copious tables, lists, descriptions, and extracts from acts of Parliament : and an account of numerous hoards or parcels of coins discovered in Scotland : and of Scottish coins found in Ireland : illustrated with upwards of 350 engravings of Scottish coins, a large number of them unpublished Author: Lindsay, John, 1789-1870 Publisher, year: Cork : Printed by Messrs. Bolster; sold, also, by Black, Edinburgh [etc.], 1845 The pages were digitized as they were. The original book may have contained pages with poor print. Marks, notations, and other marginalia present in the original volume may also appear. For wider or heavier books, a slight curvature to the text on the inside of pages may be noticeable. ISBN of reproduction: 978-1-926748-98-6 This reproduction is intended for personal use only, and may not be reproduced, re-published, or re-distributed commercially. For further information on permission regarding the use of this reproduction contact McGill University Library. McGill University Library www.mcgill.ca/library A VIEW OF THE COINAGE OF SCOTLAND, WITH COPIOUS TABLES, LISTS, DESCRIPTIONS, AND EXTRACTS FROM ACTS OF PARLIAMENT ; AND AN ACCOUNT OF NUMEROUS HOARDS OR PARCELS OF COINS DISCOVERED IN SCOTLAND, AND OF SCOTTISH COINS FOtJND IN IRELAND. ILLUSTRATED WITH UPWARDS OF 350 ENGRAVINGS OF SCOTTISH COINS, A LARGE NUMBER OF THEM UNPUBLISHED. BY JOHN LINDSAY, ESQ., BARRISTER AT LAW. Member of the British Archceological Association, Member of the Irish Archaeological Society, Corresponding Member of the Syro Egyptian Society of London, and Author of "A View of the Coinage of Ireland,*7 and of " A View of the Coinage of the Heptarchy." CORK: PRINTED BY MESSRS. -

Grace Notes Newsletter of the Memphis Scottish Society, Inc

GRACE NOTES Newsletter of the Memphis Scottish Society, Inc. Vol. 35 No. 3 • March 2019 President’s Letter From President John Schultz: The board has decided to have next year’s Burns Nicht at Woodland Hills on Burns’s birthday, January 25, 2020. The finan- cial results of the last few Burns Nichts has taken a toll on the Memphis Scottish Society’s finances. There appears to be enough Memphis in the treasury to allow one more try. Today social media is a Scottish great way to get the word out, but the Memphis Scottish Society’s web site (memphisscots.com) and Facebook page only reach people Society, Inc. looking for it. The key is for members on Facebook to share the Buns Nicht post when it becomes available. If you have connec- Board tions to traditional media let the Board know so those avenues can also be explored. President John Schultz 901-754-2419 [email protected] Vice President Sammy Rich 901-496-2193 [email protected] April 6th Is Tartan Day! Treasurer Debbie Sellmansberger National Tartan Day comes but once a year, so let’s have some 901-465-4739 fun with it. The Irish have had their St. Patrick’s Day, and now [email protected] it’s time for the Scots to have ourr day. Let’s all dress out and Secretary show off your tartan with pride! Just don’t walk over a sidewalk Mary Clausi grate like I accidentally did a few years ago (the cops roared with laughter!). 901-831-3844 [email protected] Members at Large Marcia Hayes 901-871-7565 [email protected] Kathy Schultz 901-754-2419 [email protected] March Meeting Program: Holly Staggs Presented by Sammy Rich and Friends 901-215-4839 [email protected] “The Kelpies” See page 2 for further information Tennessee Tartan. -

A Handbook to the Coinage of Scotland

Gift of the for In ^ Nflmisutadcs Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.org/details/handbooktocoinagOOrobe A HANDBOOK TO THE COINAGE OF SCOTLAND. Interior of a Mint. From a French engraving of the reign of Louis XII. A HANDBOOK TO THE COINAGE OF SCOTLAND, GIVING A DESCRIPTION OF EVERY VARIETY ISSUED BY THE SCOTTISH MINT IN GOLD, SILVER, BILLON, AND COPPER, FROM ALEXANDER I. TO ANNE, With an Introductory Chapter on the Implements and Processes Employed. BY J. D. ROBERTSON, MEMBER OF THE NUMISMATIC SOCIETY OF LONDON. LONDON: GEORGE BELL ANI) SONS, YORK STREET, COVENT GARDEN. 1878. CHISWICK PRESS C. WHITTINGHAM, TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE. TO C. W. KING, M.A., SENIOR FELLOW OF TRINITY COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE, THIS LITTLE BOOK IS GRATEFULLY INSCRIBED. CONTENTS. PAGE Preface vii Introductory Chapter xi Table of Sovereigns, with dates, showing the metals in which each coined xxix Gold Coins I Silver Coins 33 Billon Coins 107 Copper Coins 123 Appendix 133 Mottoes on Scottish Coins translated 135 List of Mint Towns, with their principal forms of spelling . 138 Index 141 PREFACE. The following pages were originally designed for my own use alone, but the consideration that there must be many collectors and owners of coins who would gladly give more attention to this very interesting but somewhat involved branch of numismatics—were they not deterred by having no easily accessible information on the subject—has in- duced me to offer them to the public. My aim has been to provide a description of every coin issued by the Scottish Mint, with particulars as to weight, fineness, rarity, mint-marks, &c., gathered from the best authorities, whom many collectors would probably not have the opportunity of consulting, except in our large public libraries ; at the same time I trust that the information thus brought together may prove sufficient to refresh the memory of the practised numismatist on points of detail. -

The Gold Metallurgy of Isaac Newton

The Gold Metallurgy of Isaac Newton E. G. V. Newman The Royal Mint, London The science of metals had always appealed to Isaac Newton and when, after the conclusion of his remarkable contributions to mathe- matics and physics, he was invited to take charge of the Royal Mint in London he was able not only to display his great gifts as an administrator but also to exercise his interest in metals and alloys and particularly in the metallurgy of gold. For over thirty years Isaac Newton lived the been accorded him for his scientific work despite the secluded life of a scholar. As undergraduate and later endeavours of his friends Samuel Pepys, John Locke Fellow and Professor at Cambridge he was shy and and Christopher Wren to secure for him a public post reserved, careless of his appearance and even more worthy of his stature. He returned to Cambridge and careless of his eating habits. This period came to a there busied himself with experimental work in triumphant conclusion, of course, with the publication chemistry and metallurgy. of the Principia in 1687. It was not until 1696 that an easement came about For a further period of thirty years, apparently by in the form of an appointment that was to effect a an astonishing transformation, Newton served his complete change in his way of life and his financial country as a highly able public official and also as the welfare. This came through the good offices of an leader of the scientific community. The achievements old friend from his undergraduate days at Trinity and the glory of the former period have not un- College whom he had re-encountered as a fellow naturally overshadowed the latter half of his working Member of Parliament, Charles Montagu. -

Histor Y at the Tower

History at the Tower Your short guide to the history of the Tower of London. Contents Visiting the Tower............................................... Page 2 Brief history of the Tower............................. Page 3 What to see............................................................ Page 5 Frequently asked questions.......................... Page 8 Page 1 Visiting the Tower Unlike most heritage sites, the Tower of London spans almost 1000 years of history, and has been the host of some of the nation’s most significant events. Because of this we would recommend that you plan your trip in advance, using the preliminary visit voucher where possible to ensure your familiarity with the Tower. The following information is a quick guide, broken into several sections: • Brief history of the Tower • What to see • Frequently asked questions about the Tower Please note that some teachers’ notes have also been prepared and can be downloaded from our website. Go to www.hrp.org.uk, navigate to Learning and then select Resources from the Related Links column. Page 2 Brief History of the Tower Roman origins The Tower was built on the south-eastern corner of the wall that the Romans built around Londinium circa AD 200. Parts of this wall are still visible within the Tower site. William the Conqueror After the successful Norman invasion, William the Conqueror set about consolidating his new capital by building three fortifications. The strongest of the three was the Tower, which controlled and protected the eastern entry to the City from the river, as well as serving as a palace. Work on the White Tower began in 1078 and probably took twenty-five years to complete. -

Architecture & Finance

bulletin Architecture & Finance 2019/20 eabh (The European Association for Banking and Financial History e.V.) Image: Bank of Canada and Museum entrance. 29 Sept 2017. Photo: doublespace UNITED KINGDOM Locations of the Royal Mint Kevin Clancy he Royal Mint has a history of over 1000 years and through that time T has had three principal homes: The Tower of London, Tower Hill and Llantrisant. But its locations and the locations where coins in Britain have been made are not nec- essarily the same. For many hundreds of years, the coins used by the peoples of Brit- ain were produced by a myriad of manu- facturers scattered throughout the country operating under licence from the monarch. In the late Anglo-Saxon period, during the reign of Ethelred II (978-1016), coins were being made in upwards of 70 towns and, even after London became more dominant from the fifteenth century, there remained regional centres of minting. Coins issued forth from ecclesiastical bases, like Can- terbury and Durham, and commercially or strategically significant towns, like Calais, retained the right to issue money on behalf of the English crown.1 What a mint looks like and the type of A plan drawn up by William Allingham in 1707 shows the Mint occupying the whole area between the buildings it occupies are closely aligned to inner and outer walls of the Tower of London on the three sides not bounded by the Thames the technology of the age governing the ways in which coins have been made. In Anglo- Saxon and early medieval times, a mint was probably not a great deal more than a few men armed with a furnace and an assort- ment of tools for cutting, weighing, assay- ing and striking small flat discs of metal. -

MEDALS and MILITARIA COINS, BANKNOTES, TOKENS And

COIN S, BANKNOTES, TOKENS and COMMEMORATIVE MEDALS Christopher Webb Director 020 7016 1801 [email protected] Peter Preston-Morley 020 7016 1802 [email protected] Jim Brown 020 7016 1803 [email protected] CONSULTANTS Nigel Mills Artefacts and Antiquities [email protected] Peter Mitchell British Hammered Coins [email protected] Michael O’Grady Paper Money [email protected] Douglas Saville Numismatic Literature [email protected] Italo Vecchi Greek and Roman Coins [email protected] Tim Wilkes Medieval, Indian and Islamic Coins [email protected] MEDALS and MILITARIA Nimrod Dix Dire ctor 020 7016 1820 [email protected] David Erskine-Hill 020 7016 1817 [email protected] Pierce Noonan Director 020 7016 1818 [email protected] Brian Simpkin 020 7016 1816 [email protected] CONSULTANTS Dixon Pickup Militaria [email protected] Brian Turner Arms and Armour [email protected] CLIENT LIAISON Christopher Hill 020 7016 1771 [email protected] UK REPRESENTATIVES Rich ard Gladdle East Midlands [email protected] Gary Charman West Midlands [email protected] Michael Trenerry West Country [email protected] Jim Stewart Scotland [email protected] OVERSEAS REPRESENTATIVES John Burridge Australia WA (61) 89 384 1218 [email protected] Tanya Ursual Canada Ontario (1) 613 258 5999 [email protected] Eiichi Ishii Japan Tokyo (81) 3 5777 0351 [email protected] Alex Kilman Russia [email protected] Natalie Jaffe South Africa Cape Town (27) 21 425 2639 [email protected] Dr Andy Singer USA Maryland (1) 301 805 7085 [email protected] -

Short Articles and Notes

SHORT ARTICLES AND NOTES A TR EM IS SIS OF JUSTIN II FOUND AT SOUTHWOLD, SUFFOLK DAVID SORENSON A GOLD tremissis of Justin II (565-78), which in March 1984 passed through the hands of a Cam- bridge coin dealer, is said to have been found by a metal-detector user on what was claimed to be a 'Saxon site near Southwold'. The coin appears to be a tremissis of Constantinople similar to Dumbarton Oaks catalogue nos. 13-141 and two 2 Of the twenty Byzantine coins or close derivatives specimens in the Bibliotheque Nationale. The of the sixth and seventh centuries found in England legends on the coin read: and listed by Rigold,3 one is a tremissis of Justin II Obv. ///I VST I NVSPPAV1 found at Canterbury and one is a solidus of Justin I Rev. VI//////AVGVSTORV1 and in ex. COHOB or II found at Richborough. The majority of coins of this period in this country are barbarous imita- It weighs 1.49 g and has a die axis of 180°. tions of imperial coins, many of them Merovingian. 1 A. R. Bellinger, Catalogue of the Byzantine Coins 3 S. E. Rigold, 'The Sutton-Hoo coins in the light of in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection 1 (Washington, 1966), the contemporary background of coinage in England', in p. 202, nos. 13-14. The Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial 1, edited by R. L. S. Bruce- 2 C. Morrisson, Catalogue des monnaies byzantines de laMitfor d (London, 1975), pp. 653-77, at 665. Bibliotheque Nationale 1 (Paris, 1970), p. -

The Elizabethan Court Day by Day--1591

1591 1591 At RICHMOND PALACE, Surrey. Jan 1,Fri New Year gifts; play, by the Queen’s Men.T Jan 1: Esther Inglis, under the name Esther Langlois, dedicated to the Queen: ‘Discours de la Foy’, written at Edinburgh. Dedication in French, with French and Latin verses to the Queen. Esther (c.1570-1624), a French refugee settled in Scotland, was a noted calligrapher and used various different scripts. She presented several works to the Queen. Her portrait, 1595, and a self- portrait, 1602, are in Elizabeth I & her People, ed. Tarnya Cooper, 178-179. January 1-March: Sir John Norris was special Ambassador to the Low Countries. Jan 3,Sun play, by the Queen’s Men.T Court news. Jan 4, Coldharbour [London], Thomas Kerry to the Earl of Shrewsbury: ‘This Christmas...Sir Michael Blount was knighted, without any fellows’. Lieutenant of the Tower. [LPL 3200/104]. Jan 5: Stationers entered: ‘A rare and due commendation of the singular virtues and government of the Queen’s most excellent Majesty, with the happy and blessed state of England, and how God hath blessed her Highness, from time to time’. Jan 6,Wed play, by the Queen’s Men. For ‘setting up of the organs’ at Richmond John Chappington was paid £13.2s8d.T Jan 10,Sun new appointment: Dr Julius Caesar, Judge of the Admiralty, ‘was sworn one of the Masters of Requests Extraordinary’.APC Jan 13: Funeral, St Peter and St Paul Church, Sheffield, of George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury (died 18 Nov 1590). Sheffield Burgesses ‘Paid to the Coroner for the fee of three persons that were slain with the fall of two trees that were burned down at my Lord’s funeral, the 13th of January’, 8s. -

2734 VOL. VIII, No. 10 NEWSLETTER the JOURNAL of the LONDON NUMISMATIC CLUB HONORARY EDITOR Peter A

ISSN 0950 - 2734 VOL. VIII, No. 10 NEWSLETTER THE JOURNAL OF THE LONDON NUMISMATIC CLUB HONORARY EDITOR Peter A. Clayton EDITORIAL 3 CLUB TALKS From Gothic to Roman: Letter Forms on the Tudor Coinage, by Toni Sawyer 5 Scottish Mints, by Michael Anderson 23 Members' Own Evening 45 Mudlarking on the Thames, by Nigel Mills 50 Patriotics and Store Cards: The Tokens of the American 1 Civil War, by David Powell 64 London Coffee-house Tokens, by Robert Thompson 79 Some Thoughts on the Copies of the Coinage of Carausius and Allectus, by Hugh Williamson 86 Roman Coins: A Window on the Past, by Ian Franklin 93 AUCTION RESULTS, by Anthony Gilbert 102 BOOK REVIEWS 104 Coinage and Currency in London John Kent The Token Collectors Companion John Whitmore 2 EDITORIAL The Club, once again, has been fortunate in having a series of excellent speakers this past year, many of whom kindly supplied scripts for publication in the Club's Newsletter. This is not as straightforward as it may seems for the Editor still has to edit those scripts from the spoken to the written word, and then to type them all into the computer (unless, occasionally, a disc and a hard copy printout is supplied by the speaker). If contributors of reviews, notes, etc, could also supply their material on disc, it would be much appreciated and, not least, probably save a lot of errors in transmission. David Berry, our Speaker Finder, has provided a very varied menu for our ten meetings in the year (January and August being the months when there is no meeting).