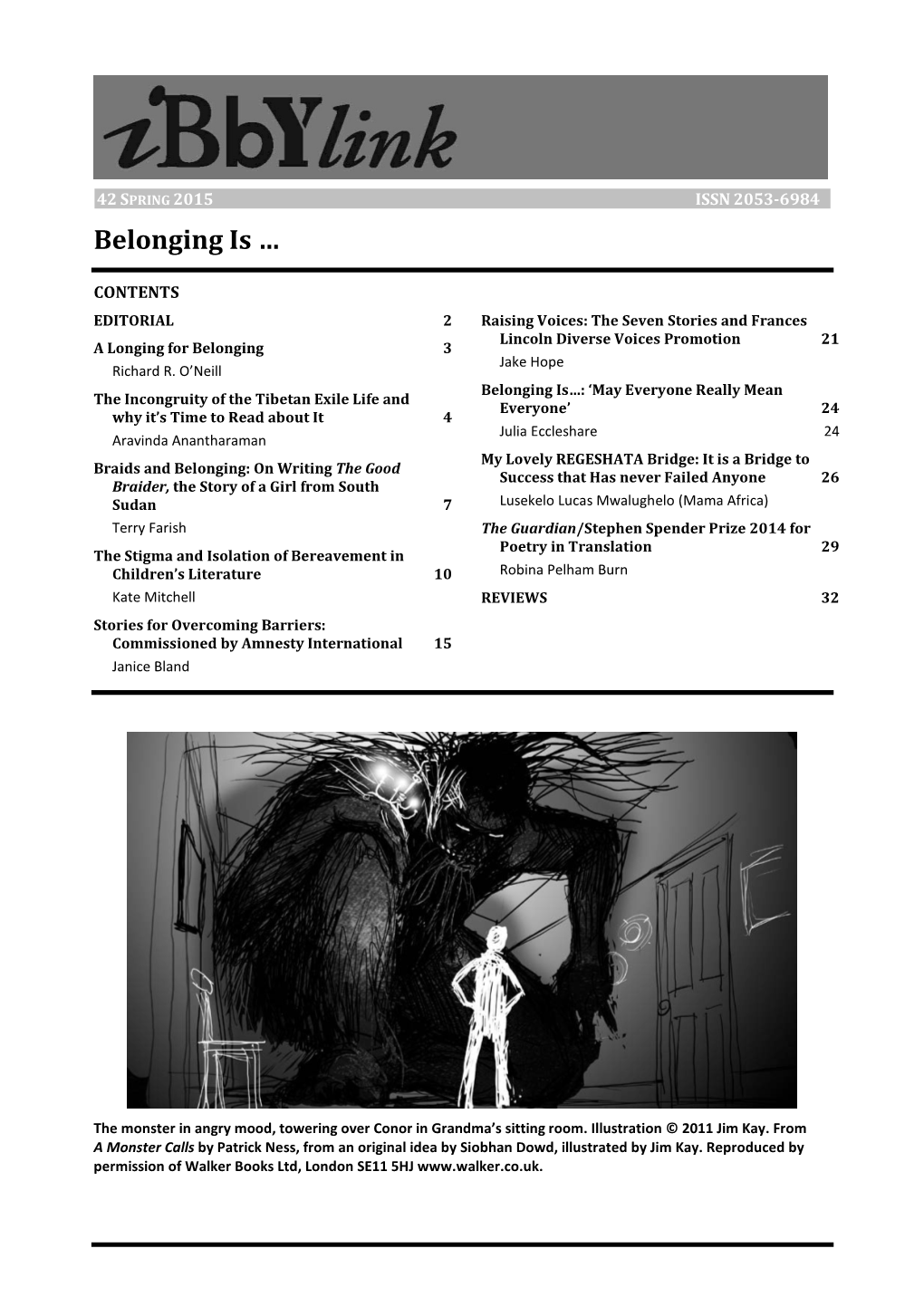

Belonging Is …

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Success and Ambiguity of Young Adult Literature: Merging Literary Modes in Contemporary British Fiction Virginie Douglas

The Success and Ambiguity of Young Adult Literature: Merging Literary Modes in Contemporary British Fiction Virginie Douglas To cite this version: Virginie Douglas. The Success and Ambiguity of Young Adult Literature: Merging Literary Modes in Contemporary British Fiction. Publije, Le Mans Université, 2018. hal-02059857 HAL Id: hal-02059857 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02059857 Submitted on 7 Mar 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Abstract: This paper focuses on novels addressed to that category of older teenagers called “young adults”, a particularly successful category that is traditionally regarded as a subpart of children’s literature and yet terminologically insists on overriding the adult/child divide by blurring the frontier between adulthood and childhood and focusing on the transition from one state to the other. In Britain, YA fiction has developed extensively in the last four decades and I wish to concentrate on what this literary emergence and evolution has entailed since the beginning of the 21st century, especially from the point of view of genre and narrative mode. I will examine the cases of recognized—although sometimes controversial—authors, arguing that although British YA fiction is deeply indebted to and anchored in the pioneering American tradition, which proclaimed the end of the Romantic child as well as that of the compulsory happy ending of the children’s book, there seems to be a recent trend which consists in alleviating the roughness, the straightforwardness of realism thanks to elements or touches of fantasy. -

33Rd IBBY International Congress, London

35 AUTUMN 2012 33rd IBBY International Congress, London CONTENTS EDITORIAL 2 Second Day of the Congress, Saturday 18 Impressions of the 33rd IBBY International Ellen Ainsworth Congress: ‘Crossing Boundaries, Translations Third and Final Day of the Congress, Sunday 19 and Migrations’ 3 Jaq Delany Darja Mazi-Leskovar, Slovenia 3 Clive Barnes, UK 4 Post-Congress Excursion, Tuesday: Discovering the Real ‘Green Knowe’ and ‘Midnight Valerie Coghlan, Ireland 5 Garden’ 20 Petros Panaou, Cyprus 6 Ellen Ainsworth Alice Curry, UK 6 Strange Migrations 22 Niklas Bengtsson, Finland 7 Shaun Tan Pam Dix, UK 8 Pat Pinsent, UK 8 REVIEWS 32 Rebecca R. Butler, UK 9 REPORTS 43 Swapna Dutta, India 10 AWARDS 44 Judith Philo, UK 11 FORTHCOMING EXHIBITIONS AND EVENTS 55 Ferelith Hordon, UK 12 NEWS 58 Susan Bailes, UK 13 IBBY NEWS 61 First Day of the Congress, Friday 15 Alexandra Strick 15 Erica Gillingham 17 Logo for the 33rd IBBY International Congress held at Imperial College London. Designed by former Children’s Laureate (2009–2011) Anthony Browne. EDITORIAL ‘ There is in London all that life can afford’ illustrator, to put into words the feelings so well (Samuel Johnson, 1777, quoted by Boswell) conveyed in his own pictures, meant that he Certainly Dr Johnson’s words could well be applied encapsulated the experience of so many of the to London in summer 2012, with the Jubilee, the children with whom IBBY is concerned. Olympics and Paralympics, and, more pertinent to The congress isn’t the only thing happening this IBBYLink, the 33rd IBBY International Congress. year – details of the annual November Many people have spoken about how heartening it IBBY/NCRCL MA conference at Roehampton are was to see so many people from different parts of given on p.61 and on the back cover. -

Child Teen Ebooks Jan 2017

EDINBURGH LIBRARIES eBOOK TITLES FOR CHILDREN & TEENS AVAILABLE ON OVERDRIVE http://yourlibrary.edinburgh.gov.uk/overdrivekids CONTENTS EARLY CHILDREN’S eBOOKS p.1-2 CFE LEVEL 1 CHILDREN’S eBOOKS p.3-6 CFE LEVEL 2 CHILDREN’S eBOOKS p.7-17 CFE LEVEL 3-5 TEEN eBOOKS p.18-34 ACCESS TO MINECRAFT TITLES p. 36 ADDITIONAL eBOOKS p. 36 Contact: [email protected] 0131 242 8047 * Book titles highlighted in red have recently been added to stock 1 EARLY CHILDREN’S EBOOKS (single access only) * A small number of our ebooks come with audio too so that children can listen and have the text highlighted at the same time. These will be marked “Talking eBook”. A - D Joy’s Greatest Joy & Simple Sadness (2 Books in 1) Peppa Meets the Queen! Peppa’s First Sleepover Farewell Grandpa Elephant by Isabel Abedi & Miriam Cordes Peepo! by Allan Ahlberg & Janet Ahlberg Every Day Dress-Up by Selina Alko Penguins, Penguins, Everywhere by Bob Barner Stars! Stars! Stars by Bob Barner Little Lou and the Woolly Mammoth by Paula Bowles (Talking eBook*) A Boy and His Bunny by Sean Bryan Never Tickle a Tiger by Pamela Butchart (Talking eBook*) Yikes, Stinkysaurus! by Pamela Butchart (Talking eBook*) Row, Row, Row Your Boat by Jane Cabrera Wizard Gold (Start Reading: Wizzle the Wizard) by Anne Cassidy Wizard Woof (Start Reading: Wizzle the Wizard) by Anne Cassidy Big Road Machines by Caterpillar The New Small Person by Lauren Child Little Pig Joins the Band by David Hyde Costello Pirates in Pyjamas by Caroline Crowe & Tom Knight Mine! by -

Children's Books Rights Guide Autumn 2017

united agents united children’s books rights guide Autumn 2017 All enquiries about translation rights unless otherwise stated to: Jane Willis (Email [email protected] Direct line + 44 20 3214 0892) Jane is assisted by Naomi Pieris Email [email protected] Direct line + 44 20 3214 2273 United Agents, 12-26 Lexington Street, London, W1F 0LE, UK Telephone + 44 20 3214 0800, www.unitedagents.co.uk 2 CONTENTS FRONTLIST PAGE NO Adult/Crossover DAEMON VOICES by Philip Pullman 4 THE GHOST WALL by Sarah Moss 5 Young Adult LUNE by Christina Wheeler 6 SATELLITE by Nick Lake 7 DARK GIFTS trilogy by Vic James 8 UNSCREWED by Helen Howe 9 11+ BIG BONES by Laura Dockrill 10 THE GOOSE ROAD by Rowena House 11 Children’s BOOK OF DUST: LA BELLE SAUVAGE by Philip Pullman 12 BILLY AND THE MINPINS by Roald Dahl, illustrated by Quentin Blake 13 SATSUMA BRIDESMAID by L A Craig 14 THE MIRACLE OF MOSES MOLE by Sandra Daniels 15 FREDERICK THE GREAT DETECTIVE by Philip Kerr 16 FENN HALFLIN AND THE SEABORN by Francesca Amour-Chelu 17 HAMISH AND THE WORLDSTOPPERS series by Danny Wallace 18 THE MATILDA EFFECT by Ellie Irving 19 THE MARSH ROAD MYSTERIES series by Elen Caldecott 20 FLAME’S STORY by Sheridan Winn 21 THE BIG GREEN BOOK by Robert Graves, illustrated by Maurice Sendak 22 BACKLIST HIGHLIGHTS Young Adult and Crossover 24 THE SHATTERED SEA trilogy by Joe Abercrombie 25 THE CELLAR by Natasha Preston 26 WHISPER TO ME by Nick Lake 27 LORALI by Laura Dockrill Children’s HIS DARK MATERIALS trilogy by Philip Pullman 28 KRINDLEKRAX by Philip Ridley -

Autumn 2020 Catalogue

ANDERSEN PRESS AUTUMN 2020 PICTURE BOOKS PICTURE BOOKS Joseph Coelho Fiona Lumbers Robert Starling LUNA LOVES ART FERGAL MEETS FERN Join Luna and Finn on a school trip at In his third story, Fergal faces his biggest the Art Gallery and step inside famous challenge yet: a little sister. masterpieces by Van Gogh, Picasso, Jackson Pollock and more! Can you spot all the art? After Fern hatches, Fergal hides his feelings of jealousy, anger and worry as he thinks At the gallery, Luna is transfixed by the famous they are bad. Luckily Dad is there to help art, but her classmate Finn doesn’t seem to him work through his emotions. want to be there at all. Finn’s family doesn’t look like the one in Henry Moore’s ‘Family SEP 2020 32pp HB 3+ Group’ sculpture, but then neither does Luna’s. 9781783449507 260 x 250mm £12.99 Maybe all Finn needs is a friend. JUL 2020 32pp HB 4+ 9781783448661 280 x 240mm £12.99 Praise for Luna Loves Library Day: FERGAL IN A FIX! ‘A touching reflection on the power of In Fergal’s second adventure he’s off to Dragon reading to bring families together’ Camp and worried about making friends. Everyone AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL will like him if he’s the best at everything . won’t ‘An ode to love and different kinds of families, they? Oh dear, Fergal, what a fix! with lyrical text and richly coloured, warm illustrations’ IRISH INDEPENDENT, Best Books of the Year SEP 2020 32pp PB 3+ 9781783448494 260 x 250mm £6.99 9781783445950 JOSEPH COELHO is a performance poet, children’s author, playwright and winner of the ‘There are life lessons galore for young readers of this Centre for Literacy in Primary Education Poetry Award 2015 for his debut poetry collection hugely appealing picture book’ LOVEREADING4KIDS Werewolf Club Rules. -

London Book Fair Children's/YA Rights Guide 2020

Children’s and YA Books 2020 CONTENTS YOUNG ADULT FICTION & NON-FICTION 3 MIDDLE-GRADE FICTION 14 ILLUSTRATED BOOKS 28 IlLLUSTRATORS 32 BACKLIST & ESTATES 38 CONTACT 48 YOUNG ADULT FICTION & NON-FICTION YOUNG ADULT FICTION THE SUMMER EVERYTHING HAPPENED by Jane Claire Bradley Junk by Melvin Burgess meets Jenni Fagan's The Panopticon. Directly informed by the author’s experiences growing up mixed-race, poor and queer on a Salford council estate, The Summer Everything Happened explores themes of home, trauma and identity – asking the question: can you ever really escape who you are and where you’re from? Agent: Silvia Molteni Winner of the Northern Debut of the Year at the Northern Writers Awards. Longlisted for the Mslexia On submission Children's and YA Novel Competition. Age: 14+ Meet Cookie: so nicknamed because she’s smart and tough Genre: Contemporary, (and because her mum doesn’t like her using her real realistic name). Cookie and her best friend Ash are sixteen, inseparable and have just finished their GCSEs. Unsure what's next but unable to face another summer on their Salford council estate, Cookie contacts her cousin, Bea, a wild child currently managing a bar in Ibiza. With no money, no passport, and a mentally ill mother struggling with PTSD from events in her past, spending the summer in Ibiza initially seems like an impossible dream for Cookie, but she and Ash are determined to get themselves to the hedonistic clubbers' paradise. But once on the White Isle, things get complicated: Ash is caught up in a risky holiday romance, Cookie's entangled in secrets, lies and dangers extending from Ibiza to home, and there's a storm coming in more ways than one. -

Typography and Narrative Voice in Children's Literature

Typography and Narrative Voice in Children’s Literature: Relationships, Interactions, and Symbiosis A Thesis submitted to the School of English at the University of Dublin, Trinity College, for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. January 2018 Louise Gallagher I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is entirely my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the Library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement. _________________________________ Louise Gallagher January 2018 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY ................................................................................................................... V ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................... VII INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 1 Typography and Paratext ....................................................................................................................... 5 Narrative Voice ....................................................................................................................................... 8 Children’s Literature and the Child Reader ......................................................................................... 10 Multimodal Literature .......................................................................................................................... -

The 22Nd Biennial Congress of Irscl

THE 22ND BIENNIAL CONGRESS OF IRSCL Held by the International Forum for Research in Children’s Literature, Institute of Humanities & Creative Arts, at the University of Worcester Saturday 8 August - Wednesday 12 August 2015 CONFERENCE PROGRAMME 2 3 CONTENTS 4 Welcome from IRSCL President 5 Welcome from the Convenor of the IRSCL 2015 Congress 6 About IRSCL 9 IRSCL Membership Information 10 Congress 2017 12 Maps 16 Practical Information 20 Keynote Speakers 24 Artists and Workshops 26 The Centre for The Picture Book in Society 28 Daily Programme 30 Master Programme 34 Panels 49 Panel Schedule 50 Panel Abstracts 85 Notes 92 Individual Papers 224 Index All attendees and details correct at time of print. Please note that this, and the ‘Individual Papers’ booklet are continuously paginated. 4 WELCOME FROM IRSCL PRESIDENT Welcome to the 22nd Congress of the International Research Society for Children’s Literature. The Society is very pleased to meet at the University of Worcester this summer: this is a university that supports the study of children’s literature at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels and that promotes scholarship in the field through its International Forum for Research in Children’s Literature and its Institute of Humanities and Creative Arts. The theme of Congress 2015 is Creating Childhoods. Conference organizers have planned a rich programme of keynote talks and scholarly papers that address various strands of this theme: childhood health and wellbeing, the child in myth and folklore, childhood in history, and the representation of children in imaginative texts. At this Congress, delegates also have the unique opportunity to participate in sessions with storytellers, artists, and performers who create texts for and with young people. -

Hay Festival

3 Our twenty-first birthday is a chance to mature our commitment to being local and global, to champion great creative writing in all welcomemedia, to respect the blessing of this staggeringly beautiful natural environment, to deepen our engagement with the most passionately held beliefs that fuel conflict around the world, and to throw ourselves headlong into the pursuit of a really good time. It’s also a new beginning, as full of possibility and audacious hope as the oak sapling that graces our cover; a new beginning for the to childrenhay who flock to Hay Fever in their half term and for all of us who’ll share stories and ideas here that will change the way we understand our lives. THE BROCHURE The redesign of the brochure makes it easier to see which events are happening simultaneously across a day in all nine venues. As previously, most events last an hour. Films have timings shown. We aim to start promptly, and we only change venues when absolutely necessary to accommodate our audience. Changes will be announced on the venue screens and online each morning. WORKSHOPS We are thrilled to be able to host more workshops for adults and children this year in the Book People’s Workshop and the Sky Learning Zone. You’ll find these events listed on the second page of each day’s listing in this brochure. GREENPRINT TRANSPORT Alongside the shuttle service to Hay town centre, the Hay 21 Bus will be running between the festival site and Hereford railway station to connect with rail services. -

The Primary English Encyclopedia: the Heart of the Curriculum, Third

The Primary English ENCYCLOPEDIA The Primary English ENCYCLOPEDIA The Heart of the Curriculum THIRD EDITION Margaret Mallett with a Foreword by Sue Palmer First published in Great Britain in 2002 by David Fulton Publishers Second edition 2005 This edition published 2008 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2008. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” © 2002, 2005, 2008 Margaret Mallett Note: The right of Margaret Mallett to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data ISBN 0-203-93182-3 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 10: 0-415-45103-5 (Print Edition) ISBN 13: 978-0-415-45103-1 Contents Foreword by Sue Palmer vii Acknowledgements ix About this Encyclopedia xi Introduction. -

(Dir.), Les Cultures Ado : Consommation Et Production

2018-n°1 Heather Braun, Elisabeth Lamothe, Delphine Letort (dir.), Les Cultures ado : consommation et production « The Success and Ambiguity of Young Adult Literature: Merging Literary Modes in Contemporary British Fiction » Virginie Douglas (Senior Lecturer in the Department of English Studies at the University of Rouen) Cette œuvre est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International Résumé Cet article se penche sur les romans destinés aux grands adolescents ou « jeunes adultes », catégorie qui connaît un engouement particulier et que l’on considère traditionnellement comme une subdivision de la littérature pour la jeunesse bien que, d’un point de vue terminologique, elle mette en avant le dépassement de la division adulte/enfant en brouillant les frontières entre ces deux âges de la vie pour mieux se concentrer sur la transition d’un état vers un autre. En Grande-Bretagne, la fiction pour jeunes adultes s’est développée de façon significative au cours des quatre dernières décennies ; cet article s’intéresse aux effets qu’ont eus cette émergence et cette évolution littéraires depuis le début du XXIe siècle, en particulier en termes de genre et de mode de narration. La fiction britannique pour jeunes adultes est ancrée dans la tradition américaine, pionnière en la matière, dont elle s’inspire largement et qui a mis un terme à une vision romantique de l’enfance ainsi qu’à l’obligation du happy ending dans le livre pour enfants. Cependant, une tendance récente semble s’employer à atténuer un réalisme âpre et brutal grâce à des éléments, voire de petites touches de fantasy. -

Psychoanalysis and Narrative in Young Adult Fiction

Re-mapping Adolescence: Psychoanalysis and Narrative in Young Adult Fiction ~ervatJ\IJomaa A Thesis Submitted for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy to The School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics The University of Sheffield September 2009 Abstract The start of the new millennium has witnessed literary interest in young adult fiction and a prominent rise in its popUlarity. My research focuses on the dynamics of adolescent narrative and the representations of the adolescent subject in a number of contemporary mainstream young adult novels with the aim of understanding adolescence as an inscribed literary identity. I take, as my starting point, Julia Kristeva's definition of adolescence as an open, non-biologically limited, psychic structure. This notion, when applied to young adult fiction, suggests that the texts work to construct psychologically-open implied readers, which in diverse ways echo and affirm the desires and expectations of real readers. While the introduction surveys contemporary critical currents in children and young adult fiction and places my research into context, each of the subsequent chapters examines one or more literary works by a single author. The main literary works discussed in this study include novels by Meg Rosoff, Geraldine McCaughrean, David Almond, lK. Rowling and Philip Pullman respectively; all of whom have widely appealed to readers of different age groups. In my analysis I use insights from psychoanalytic and psycho-linguistic theories mainly by Kristeva, Freud, Lacan and Winnicott, and where necessary my argument is supported by narrative analysis, reading theories and feminist criticism. By engaging with critical and psychoanalytical readings of paradigmatic young adult.