Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Household and Structural Pest Management for Professionals

Professional Pest Control Rev. 2/17 Household and Structural Pest Management for Professionals See The UT E&PP Redbook, Household and Structural Pests section (https://ag.tennessee.edu/EPP/Pages/Household-Structural.aspx) for information related to preventing and otherwise managing pests using integrated pest management. More information for the pest management professional can be found in the following UT Extension Publications https://ag.tennessee.edu/PSEP/Pages/studymanuals.aspx Vail, K.M., G. Burgess, R. Gerhardt and C. Harper [eds.]. 2007. PB1673 General Pest and Rodent Control Pesticide Applicator Licensing Manual (GRC). pp. 130. Vail, K., G. Burgess , R. Gerhardt and C. Jones [eds.]. 2002. PB1685 Public Health Mosquito Control: The Tennessee Mosquito Control Handbook (Pesticide Applicator Licensing Manual). pp. 54. Vail, K., G. Burgess, C. Pless and B. Bonds [eds.]. 2006. PB 1703 Wood-Destroying Organisms Licensing Manual. Vail, K.M., E. Burgess, R. Gerhardt, and Craig Harper. 2006. PB1732 Industrial, Institutional, Structural and Health Related Pest Management Certification Manual (Category 7). pp. 105 Vail, K.M., E.E. Burgess, R. Gerhardt, C. Jones, J. Skinner and C. Harper. 2003. PB1733. Public Health Pest Control (Certification Category 8). pp. 99 Further references for household pest identification: Manuals: Bennett, G. W., J. M. Owens, & R. M. Corrigan. 2011. Scientific Guide to Pest Management Operations, seventh edition Cleveland, OH: Questex Publishing. Mallis, A. 2011. Handbook of Pest Control - the Behavior, Life History and Control of Household Pests. 10th edition. Mallis Handbook LLC. Field Guides Hedges, S. 2010. Pest Control Technology Field Guide for the Management of Structure-Infesting Ants, 3rd edition. -

WBF Convention Card 2.19 REOPENING:Cue Bid Is Only Forcing, Can Be Weaker; RESP= Suit 4Th 4Th NAT NT 4Th 4Th Category: Natural - GREEN Subseq Low=Encourage High=Disc

DEFENSIVE AND COMPETITIVE BIDDING LEADS AND SIGNALS OVERCALLS (Style; Responses; 1/2 Level; Reopening) OPENING LEADS STYLE Sound; CUE-BID RESP:Promises support,Jump RAISE=PRE Lead In Partner's Suit WBF Convention Card 2.19 REOPENING:Cue bid is only forcing, Can be weaker; RESP= Suit 4th 4th NAT NT 4th 4th Category: Natural - GREEN Subseq low=encourage high=disc. low=encourage high=disc. Country: CHINESE TAIPEI Other: Ace=request S/p, king=count Event: Players: VIOLET LIU JOYCE HSU 1NT OVERCALL (2ND/4TH Live; Responses; Reopening) LEADS SYSTEM SUMMARY 2nd POS:15-18HCP; Same as 1NT Opening Lead Vs. Suit Vs. NT GENERAL APPROACH AND STYLE 4th POS:13-15HCP; Same as 1NT Opening Ace AK; Axx(+) AK;AKx(+) Natural; 5-card M; 1NT resp:F1(6-12)/1M; PRE:Classic; King KQ;AKx(+);AKJ10(+)KQ109x KQ;KQx(+)AKJ10(+)KQ109(+ Mutil 2D/H/S Opening; Limit jump raises/M;Weak jump Queen KQ109;QJ;QJx(+) QJ;QJx(+);KQ109 shift VS overcall. Jack AQJX;J10x(+); J10;J10x(+);HQJXX(+) JUMP OVERCALLS (Style; Responses; Unusual NT) 10 109;109x(+);HJ10(+);10x 109;109x(+);HJ10Xx(+) 1-Suit: WEAK; 2NT:asking strength and suit Quality 9 9x;98x(+);H98XX 98x(+) 2-Suit: 2NT=lower 2 unbid suits: Hi-x Sx;xSx Sx;Sxx;xSxx 1NT Openings: 15-18- HCP H+om; (1M)-2NT: D+C UNLIMITED Lo-x HxS;HxxS(+);xxxS(+) HxS;HxxS(+);xxxS(+) 2 OVER 1 Responses: Promises rebid Reopen: 2NT=NAT SIGNALS IN ORDER OF PRIORITY SPECIAL BIDS THAT MAY REQUIRE DEFENCE DIRECT and JUMP CUE BIDS (Style; Responses; Reopen) Partners Lead Declarer's Lead Discarding GAMBLING 3NT(SOL m,with 1/2 side suit STOP) MICHAELS CUE: (1m)-2m:H+S (54+); (1M)-2M:OM+m (55+); Suit:1st Hi/lo=D same EVEN=DISCOURAGE LEBENSOHL;MICHAEL Cue Bid over NAT Openig, Unlimit Seeking stopper. -

Appendix O to the ACBL General Conditions of Contest: Online Play

Appendix O to the ACBL General Conditions of Contest: Online Play 1) Cheating: Cheating online is a serious offense, subject to the same penalties as cheating in live play. It is illegal to communicate with your partner during a hand via any means other than chat to the full table, to communicate with a kibitzer during the game, to play using an account that is not yours, to gain advanced knowledge of a deal, or to play in one event using multiple accounts. Any accusation of cheating must be made privately to the director of the event, to the ACBL Recorder, or to a reporting mechanism provided by the online platform. 2) Alerts: Alerts (including announcements) are made by the player making the call. An alerted call should be accompanied by an explanation. Stating the common or popular name of the convention is not sufficient. You are encouraged to explain calls even if those calls do not require alerts. Any call that would be alerted after the auction in live bridge should be alerted at the time of the call. 3) Any contestant may request information concerning an opponent’s methods. Such inquiries should be directed to the player who made the call and must be asked in a private chat. Replies to these inquiries must likewise be given in a private chat. When playing with a Zoom (or the equivalent) screenmate follow up questions are permitted regardless of which player made the call or play. 4) Tempo: In general, bids and plays within 10 seconds are considered to be in tempo. -

Courtesy of Mary Jane Kinnebrew

Online Chat abbreviations – Courtesy of Mary Jane Kinnebrew ------------------------------------- AFAIK: as far as I know AFK: away from keyboard ASAP: as soon as possible A/S/L?: age, sex, location B4: before B4N: bye for now BAK: back at the keyboard BBN: bye bye now BFN: bye for now BRB: be right back BTW: by the way CU: see you CUL or CUL8ER: see you later CUZ: because F2F: face to face FAQ: frequently asked question(s) FC fingers crossed FWIW: for what it’s worth FYI: for your information GA: go ahead GTG: Got to Go. IAC: in any case IC: I see IDK: I don’t know IIRC: if I remember correctly ILU: I love you IM: instant message IMHO: in my humble opinion IMing: chatting with someone online IMNSHO: in my not so humble opinion IMO: in my opinion JK: just kidding K: okay KIT: keep in touch LOL: 1. Laughing out loud. 2. Little Old Lady. L8R: later M/F: male or female MSG: message N/P: no problem OIC: oh I see OMG: oh my god OTOH: on the other hand PLZ: please PM: private message ROFL: rolling on the floor laughing SUP or WU: what’s up THX: Thanks TX: Thanks. TU: thank you UW: you’re welcome WB: welcome back WTG: Way to go! WYSIWYG: what you see is what you get Online Bridge abbreviations ---------------------------------------- 2/1 : 1. Two-over-one response (e.g. 1H : 2C). 2. Abbreviation for the 2/1 Game Force bidding system, in which a two-over-one response (with the exception of responses to 1NT) is forcing to game. -

Bernard Magee's Acol Bidding Quiz

Number: 189 UK £3.95 Europe €5.00 September 2018 Bernard Magee’s Acol Bidding Quiz This month we are dealing with auctions where the opponents make an early double. You are West in BRIDGEthe auctions below, playing ‘Standard Acol’ with a weak no-trump (12-14 points) and four-card majors. It is your turn to call. 1. Dealer East. Love All. 4. Dealer East. Love All. 7. Dealer West. Love All. 10. Dealer East. Love All. ♠ J 7 6 5 ♠ 3 2 ♠ A 4 3 ♠ 6 3 ♥ K 2 N ♥ A 8 6 N ♥ A J 7 6 5 N ♥ 5 4 3 N W E W E W E W E ♦ K 3 2 S ♦ 9 7 6 S ♦ K 2 S ♦ 9 4 3 S ♣ 9 7 6 5 ♣ K Q 10 5 4 ♣ A 9 7 ♣ Q 8 7 6 5 West North East South West North East South West North East South West North East South 1♦ Dbl 1NT Dbl 1♥ Dbl Pass 1NT 1♠ Dbl ? ? ? Pass 2♥ Dbl Pass ? 2. Dealer East. Love All. 5. Dealer East. Love All. 8. Dealer West. Love All. 11. Dealer East. Love All. ♠ J 8 7 ♠ 8 7 2 ♠ A 4 3 ♠ Q 8 7 6 ♥ J 8 4 2 N ♥ A 8 6 5 N ♥ A 8 6 5 N ♥ 4 2 N W E ♦ 2 W E W E W E S ♦ 4 3 2 ♦ A 9 2 ♦ K 4 3 S S S ♣ A J 9 6 5 ♣ 8 7 5 ♣ A 9 7 ♣ K 7 6 5 West North East South West North East South West North East South West North East South 1♥ Dbl 1NT Dbl 1♥ Dbl 1NT Pass 1♠ Pass ? ? ? 2♠ Dbl 3♠ Pass ? 3. -

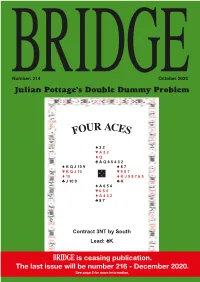

FOUR ACES Could Have Done More Safely

Number: 214 October 2020 BRIDGEJulian Pottage’s Double Dummy Problem UR ACE FO S ♠ 3 2 ♥ A 3 2 ♦ Q ♣ A Q 6 5 4 3 2 ♠ K Q J 10 9 ♠ 8 7 ♥ N ♥ K Q J 10 W E 9 8 7 ♦ 10 S ♦ K J 9 8 7 6 5 ♣ J 10 9 ♣ K ♠ A 6 5 4 ♥ 6 5 4 ♦ A 4 3 2 ♣ 8 7 Contract 3NT by South Lead: ♠K BRIDGE is ceasing publication. The last issueThe will answer be will benumber published on page 216 4 next - month.December 2020. See page 5 for more information. A Sally Brock Looks At Your Slam Bidding Sally’s Slam Clinic Where did we go wrong? Slam of the month Another regular contributor to these Playing standard Acol, South would This month’s hand was sent in by pages, Alex Mathers, sent in the open 2♣, but whatever system was Roger Harris who played it with his following deal which he bid with played it is likely that he would then partner Alan Patel at the Stratford- his partner playing their version of rebid 2NT showing 23-24 points. It is upon-Avon online bridge club. Benjaminised Acol: normal to play the same system after 2♣/2♦ – negative – 2NT as over an opening 2NT, so I was surprised North Dealer South. Game All. Dealer West. Game All. did not use Stayman. In my view the ♠ A 9 4 ♠ J 9 8 correct Acol sequence is: ♥ K 7 6 ♥ A J 10 6 ♦ 2 ♦ K J 7 2 West North East South ♣ A 9 7 6 4 2 ♣ 8 6 Pass Pass Pass 2♣ ♠ Q 10 8 6 3 ♠ J 7 N ♠ Q 4 3 ♠ 10 7 5 2 Pass 2♦ Pass 2NT ♥ Q 9 ♥ 10 8 5 4 2 W E ♥ 7 4 3 N ♥ 9 8 5 2 Pass 3♣ Pass 3♦ ♦ Q J 10 9 5 ♦ K 8 7 3 S W E ♦ 8 5 4 ♦ Q 9 3 Pass 6NT All Pass ♣ 8 ♣ Q 5 S ♣ Q 10 9 4 ♣ J 5 Once South has shown 23 HCP or so, ♠ K 5 2 ♠ A K 6 North knows the values are there for ♥ A J 3 ♥ K Q slam. -

The Foundation System

The Foundation System Notrump Bidding Introduction This chapter treats hands in which Opener holds a balanced hand (4333, 4432, 5332 with a 5-card minor, perhaps occasionally 5422 or 6322 with a 6-card minor or 5332 with a weak 5-card major) of three different strength ranges: 15-17 HCP (1NT opening), 20-21 HCP (2NT opening), or 22+ HCP (2C opening followed by a 2NT rebid by Opener). Other strength ranges are treated in the chapter on Minor Suit Bidding: 12-14 HCP (1C or 1D followed by a 1NT rebid by Opener) and 18-19 HCP (1C or 1D followed by a 2NT rebid). A 5-card major is acceptable for the stronger openings (2NT and 2C then 2NT). These strength ranges are not absolute. A bad 15 HCP can always be downgraded to open 1C or 1D; a bad 18 HCP can be downgraded to open 1NT; and a bad 22 HCP can be opened 2NT. The Bridge World magazine maintains a system called Bridge World Standard which is based on the preferences of a panel of experts; their notrump ranges are expressed as a good 15 to a bad 18, and a good 20 to a bad 22. Further discussion of such adjustments will be deferred until the Bidding Practice quizzes in Part II. Responses to 1NT Note: Unless otherwise noted in the discussion, these same responses and rebids apply, but obviously one level higher, after a 2NT opening , and also after 2C/P/2any/P/2NT (so long as the 2any response is artificial and does not show any specific suit). -

A Quick Reference Guide to Pesticides for Pest Management Professionals Working in and Around Structures 2020

W 658 A Quick Reference Guide to Pesticides for Pest Management Professionals Working in and Around Structures 2020 A Quick Reference Guide to Pesticides for Pest Management Professionals Working in and Around Structures Karen Vail, Professor, and Jennifer Chandler, Research Specialist III, Entomology and Plant Pathology This publication provides a quick reference to pesticides and methods for the pest management professional to use in solving pest management problems in and around structures. A thorough description of pest identification including images, inspection and detection techniques, exclusion, sanitation, other environmental modifications, and pesticide formulations can be found in the following UT Extension publications (https://ag.tennessee.edu/PSEP/Forms/F818.pdf): Vail, K.M., G. Burgess, R. Gerhardt and C. Harper [eds.]. 2007. PB 1673 General Pest and Rodent Control Pesticide Applicator Licensing Manual (GRC). pp. 130. Vail, K., G. Burgess, R. Gerhardt and C. Jones [eds.]. 2002. PB 1685 Public Health Mosquito Control: The Tennessee Mosquito Control Handbook (Pesticide Applicator Licensing Manual). pp. 54. Vail, K., D. Hensley, G. Burgess, C. Pless and A. Taylor [eds.]. 2014. PB 1703 Wood-Destroying Organisms Licensing Manual. pp. 76. Vail, K.M., E. Burgess, R. Gerhardt, and Craig Harper. 2006. PB 1732 Industrial, Institutional, Structural and Health Related Pest Management Certification Manual (Category 7). pp. 105. Vail, K.M., E.E. Burgess, R. Gerhardt, C. Jones, J. Skinner and C. Harper. 2003. PB 1733. Public Health Pest Control (Category 8). pp. 99. Further references for household pest identification: Manuals: Bennett, G.W., J.M. Owens, & R.M. Corrigan. 2011. Scientific Guide to Pest Management Operations, seventh edition Cleveland, OH: Questex Publishing. -

National Convention 2009

National Convention 2009 American Association for the Advancement of Slavic Studies November 12–15, 2009 Boston, Massachusetts American Association for the Advancement of Slavic Studies 41st National Convention November 12–15, 2009 Marriott Copley Place Boston, Massachusetts American Association for the Advancement of Slavic Studies 8 Story Street, 3rd fl oor Cambridge, MA 02138 tel.: 617-495-0677, fax: 617-495-0680 e-mail: [email protected] web site: www.aaass.org iii CONTENTS Convention Schedule Overview ................................................................. iv List of the Meeting Rooms at the Marriott Copley Place ............................ v Diagrams of Meeting Rooms .................................................................vi–ix Exhibit Hall Diagram ...................................................................................x Index of Exhibitors, Alphabetical................................................................ xi Index of Exhibitors, by Booth Number .......................................................xii 2009 AAASS Board of Directors ...............................................................xiii AAASS National Offi ce .............................................................................xiii Program Committee for the Boston, MA Convention ................................xiii AAASS Affi liates .......................................................................................xiv 2009 AAASS Institutional Members ......................................................... xv Program -

Calling Time (Bidding and Playing in Tempo)

Calling Time (Bidding and Playing in Tempo) 1. Introduction The Laws of Duplicate Bridge say that it is “desirable for players to maintain steady tempo and unvarying manner”. Sometimes this is easier said than done, and all of us hesitate from time to time before making a call or playing a card – which is perfectly acceptable. That is, unless: a) it is intended to convey some extraneous information to your partner. b) it is deliberately supposed to mislead the other side (like hesitating with a singleton). Please read on to find out why and when even normal hesitations can be a problem and also how to improve your play in tempo - and why this can be to your advantage! 2. Hesitation in the Auction Whenever you hesitate before making a call, you are indicating that you have a choice of actions which may be very useful Authorised Information for your opponents, who are perfectly at liberty to take full advantage. It is also providing Unauthorised Information to your partner, who must make every effort to avoid making any call that your hesitation might indicate. Your partner may then have a very awkward ethical dilemma and feel obliged to demonstrate that your hesitation did not influence their choice of call and to not make that excellent bid they had in mind. The same is true if you make your call with such speed that everyone knows you have a Yarborough, or in such a way as to draw your partner's attention to it (this 2C is Landy, partner!). Here are some tips to help you make your calls in tempo, which will also avoid you giving useful information to your opponents and making problems for your partner: a) Always pause for 3 seconds before every bid, but make that 10 after your RHO's jump bid. -

Bernard Magee's Acol Bidding Quiz

Number: 177 UK £3.95 Europe €5.00 September 2017 Bernard Magee’s Acol Bidding Quiz This month we are dealing with hands with two long suits. You are West in the auctions below, BRIDGEplaying ‘Standard Acol’ with a weak no-trump (12-14 points) and four-card majors. 1. Dealer West. Game All. 4. Dealer East. Love All. 7. Dealer West. Love All. 10. Dealer West. Love All. ♠ J 7 6 5 4 3 ♠ A 8 7 6 5 ♠ 3 ♠ 7 6 ♥ Q 8 6 4 2 N ♥ 9 3 N ♥ A K Q 3 2 N ♥ K Q 8 7 6 N W E W E W E ♦ A Q ♦ K Q 8 6 2 W E ♦ A J 5 4 2 ♦ A K 8 3 2 S ♣ Void S ♣ 2 S ♣ 7 5 S ♣ 2 West North East South West North East South West North East South West North East South ? 1♥ Pass 1♥ 1♠ 2♥ 3♠ 1♥ 1♠ 2♣ 2♠ 1♠ Pass 2♣ Pass ? ? ? 2. Dealer West. Love All. 5. Dealer East. Love All. 8. Dealer East. E/W Game. 11. Dealer West. N/S Game. ♠ A 8 ♠ K Q J 8 7 ♠ 7 3 2 ♠ Void ♥ K Q 4 3 2 N ♥ A K N ♥ A K 8 4 3 N ♥ K Q 8 7 6 N W E W E W E W E ♦ A K 8 7 2 ♦ Q J 6 4 3 ♦ 5 2 ♦ Q J 4 S S S S ♣ 2 ♣ 6 ♣ K J 4 ♣ A Q 8 7 6 West North East South West North East South West North East South West North East South 1♥ Pass 1♠ Pass 1NT Pass 1♣ 1♠ 1♥ 1♠ 2♣ 2♠ ? 2♥1 Pass 2♠ Pass 2♥ 3♠ 4♥ 4♠ ? ? 1Transfer to spades ? 3. -

The Critics: Poetry Is About Poetry 23 V

Love and its Critics From the Song of Songs to Shakespeare and Milton’s Eden MICHAEL BRYSON AND ARPI MOVSESIAN To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/611 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Love and its Critics From the Song of Songs to Shakespeare and Milton’s Eden Michael Bryson and Arpi Movsesian https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2017 Michael Bryson and Arpi Movsesian This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Michael Bryson and Arpi Movsesian, Love and its Critics: From the Song of Songs to Shakespeare and Milton’s Eden. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2017, https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0117 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/611#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www.