2.4. Constraints

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SAP IQ Administration: User Management and Security Company

ADMINISTRATION GUIDE | PUBLIC SAP IQ 16.1 SP 04 Document Version: 1.0.0 – 2019-04-05 SAP IQ Administration: User Management and Security company. All rights reserved. All rights company. affiliate THE BEST RUN 2019 SAP SE or an SAP SE or an SAP SAP 2019 © Content 1 Security Management........................................................ 5 1.1 Plan and Implement Role-Based Security............................................6 1.2 Roles......................................................................7 User-Defined Roles.........................................................8 System Roles............................................................ 30 Compatibility Roles........................................................38 Views, Procedures, and Tables That Are Owned by Roles..............................38 Display Roles Granted......................................................39 Determining the Roles and Privileges Granted to a User...............................40 1.3 Privileges..................................................................40 Privileges Versus Permissions.................................................41 System Privileges......................................................... 42 Object-Level Privileges......................................................64 System Procedure Privileges..................................................81 1.4 Passwords.................................................................85 Password and user ID Restrictions and Considerations...............................86 -

*** Check Constraints - 10G

*** Check Constraints - 10g *** Create table and poulated with a column called FLAG that can only have a value of 1 or 2 SQL> CREATE TABLE check_const (id NUMBER, flag NUMBER CONSTRAINT check_flag CHECK (flag IN (1,2))); Table created. SQL> INSERT INTO check_const SELECT rownum, mod(rownum,2)+1 FROM dual CONNECT BY level <=10000; 10000 rows created. SQL> COMMIT; Commit complete. SQL> exec dbms_stats.gather_table_stats(ownname=>NULL, tabname=>'CHECK_CONST', estimate_percent=> NULL, method_opt=> 'FOR ALL COLUMNS SIZE 1'); PL/SQL procedure successfully completed. *** Now perform a search for a value of 3. There can be no such value as the Check constraint only permits values 1 or 2 ... *** The exection plan appears to suggest a FTS is being performed (remember, there are no indexes on the flag column) *** But the statistics clearly show no LIOs were performed, none SQL> SELECT * FROM check_const WHERE flag = 3; no rows selected Execution Plan ---------------------------------------------------------- Plan hash value: 1514750852 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- | Id | Operation | Name | Rows | Bytes | Cost (%CPU)| Time | ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- | 0 | SELECT STATEMENT | | 1 | 6 | 0 (0)| | |* 1 | FILTER | | | | | | |* 2 | TABLE ACCESS FULL| CHECK_CONST | 1 | 6 | 6 (0)| 00:00:01 | ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Predicate Information (identified by operation id): --------------------------------------------------- -

Chapter 10. Declarative Constraints and Database Triggers

Chapter 10. Declarative Constraints and Database Triggers Table of contents • Objectives • Introduction • Context • Declarative constraints – The PRIMARY KEY constraint – The NOT NULL constraint – The UNIQUE constraint – The CHECK constraint ∗ Declaration of a basic CHECK constraint ∗ Complex CHECK constraints – The FOREIGN KEY constraint ∗ CASCADE ∗ SET NULL ∗ SET DEFAULT ∗ NO ACTION • Changing the definition of a table – Add a new column – Modify an existing column’s type – Modify an existing column’s constraint definition – Add a new constraint – Drop an existing constraint • Database triggers – Types of triggers ∗ Event ∗ Level ∗ Timing – Valid trigger types • Creating triggers – Statement-level trigger ∗ Option for the UPDATE event – Row-level triggers ∗ Option for the row-level triggers – Removing triggers – Using triggers to maintain referential integrity – Using triggers to maintain business rules • Additional features of Oracle – Stored procedures – Function and packages – Creating procedures – Creating functions 1 – Calling a procedure from within a function and vice versa • Discussion topics • Additional content and activities Objectives At the end of this chapter you should be able to: • Know how to capture a range of business rules and store them in a database using declarative constraints. • Describe the use of database triggers in providing an automatic response to the occurrence of specific database events. • Discuss the advantages and drawbacks of the use of database triggers in application development. • Explain how stored procedures can be used to implement processing logic at the database level. Introduction In parallel with this chapter, you should read Chapter 8 of Thomas Connolly and Carolyn Begg, “Database Systems A Practical Approach to Design, Imple- mentation, and Management”, (5th edn.). -

Reasoning Over Large Semantic Datasets

R O M A TRE UNIVERSITA` DEGLI STUDI DI ROMA TRE Dipartimento di Informatica e Automazione DIA Via della Vasca Navale, 79 – 00146 Roma, Italy Reasoning over Large Semantic Datasets 1 2 2 1 ROBERTO DE VIRGILIO ,GIORGIO ORSI ,LETIZIA TANCA , RICCARDO TORLONE RT-DIA-149 May 2009 1Dipartimento di Informatica e Automazione Universit`adi Roma Tre {devirgilio,torlone}@dia.uniroma3.it 2Dipartimento di Elettronica e Informazione Politecnico di Milano {orsi,tanca}@elet.polimi.it ABSTRACT This paper presents NYAYA, a flexible system for the management of Semantic-Web data which couples an efficient storage mechanism with advanced and up-to-date ontology reasoning capa- bilities. NYAYA is capable of processing large Semantic-Web datasets, expressed in a variety of formalisms, by transforming them into a collection of Semantic Data Kiosks that expose the native meta-data in a uniform fashion using Datalog±, a very general rule-based language. The kiosks form a Semantic Data Market where the data in each kiosk can be uniformly accessed using conjunctive queries and where users can specify user-defined constraints over the data. NYAYA is easily extensible and robust to updates of both data and meta-data in the kiosk. In particular, a new kiosk of the semantic data market can be easily built from a fresh Semantic- Web source expressed in whatsoever format by extracting its constraints and importing its data. In this way, the new content is promptly available to the users of the system. The approach has been experimented using well known benchmarks with very promising results. 2 1 Introduction Ever since Tim Berners Lee presented, in 2006, the design principles for Linked Open Data1, the public availability of Semantic-Web data has grown rapidly. -

CSC 443 – Database Management Systems Data and Its Structure

CSC 443 – Database Management Systems Lecture 3 –The Relational Data Model Data and Its Structure • Data is actually stored as bits, but it is difficult to work with data at this level. • It is convenient to view data at different levels of abstraction . • Schema : Description of data at some abstraction level. Each level has its own schema. • We will be concerned with three schemas: physical , conceptual , and external . 1 Physical Data Level • Physical schema describes details of how data is stored: tracks, cylinders, indices etc. • Early applications worked at this level – explicitly dealt with details. • Problem: Routines were hard-coded to deal with physical representation. – Changes to data structure difficult to make. – Application code becomes complex since it must deal with details. – Rapid implementation of new features impossible. Conceptual Data Level • Hides details. – In the relational model, the conceptual schema presents data as a set of tables. • DBMS maps from conceptual to physical schema automatically. • Physical schema can be changed without changing application: – DBMS would change mapping from conceptual to physical transparently – This property is referred to as physical data independence 2 Conceptual Data Level (con’t) External Data Level • In the relational model, the external schema also presents data as a set of relations. • An external schema specifies a view of the data in terms of the conceptual level. It is tailored to the needs of a particular category of users. – Portions of stored data should not be seen by some users. • Students should not see their files in full. • Faculty should not see billing data. – Information that can be derived from stored data might be viewed as if it were stored. -

Data Base Lab the Microsoft SQL Server Management Studio Part-3

Data Base Lab Islamic University – Gaza Engineering Faculty Computer Department Lab -5- The Microsoft SQL Server Management Studio Part-3- By :Eng.Alaa I.Haniy. SQL Constraints Constraints are used to limit the type of data that can go into a table. Constraints can be specified when a table is created (with the CREATE TABLE statement) or after the table is created (with the ALTER TABLE statement). We will focus on the following constraints: NOT NULL UNIQUE PRIMARY KEY FOREIGN KEY CHECK DEFAULT Now we will describe each constraint in details. SQL NOT NULL Constraint By default, a table column can hold NULL values. The NOT NULL constraint enforces a column to NOT accept NULL values. The NOT NULL constraint enforces a field to always contain a value. This means that you cannot insert a new record, or update a record without adding a value to this field. The following SQL enforces the "PI_Id" column and the "LName" column to not accept NULL values CREATE TABLE Person ( PI_Id int NOT NULL, LName varchar(50) NOT NULL, FName varchar(50), Address varchar(50), City varchar(50) ) 2 SQL UNIQUE Constraint The UNIQUE constraint uniquely identifies each record in a database table. The UNIQUE and PRIMARY KEY constraints both provide a guarantee for uniqueness or a column or set of columns. A PRIMARY KEY constraint automatically has a UNIQUE constraint defined on it. Note that you can have many UNIQUE constraints per table, but only one PRIMARY KEY constraint per table. SQL UNIQUE Constraint on CREATE TABLE The following SQL creates a UNIQUE -

Declarative Constraints

THREE Declarative Constraints 3.1 PRIMARY KEY 3.1.1 Creating the Constraint 3.1.2 Naming the Constraint 3.1.3 The Primary Key Index 3.1.4 Sequences 3.1.5 Sequences in Code 3.1.6 Concatenated Primary Key 3.1.7 Extra Indexes with Pseudo Keys 3.1.8 Enable, Disable, and Drop 3.1.9 Deferrable Option 3.1.10 NOVALIDATE 3.1.11 Error Handling in PL/SQL 3.2 UNIQUE 3.2.1 Combining NOT NULL, CHECK with UNIQUE Constraints 3.2.2 Students Table Example 3.2.3 Deferrable and NOVALIDATE Options 3.2.4 Error Handling in PL/SQL 3.3 FOREIGN KEY 3.3.1 Four Types of Errors 3.3.2 Delete Cascade 3.3.3 Mandatory Foreign Key Columns 3.3.4 Referencing the Parent Syntax 3.3.5 Referential Integrity across Schemas and Databases 3.3.6 Multiple Parents and DDL Migration 3.3.7 Many-to-Many Relationships 3.3.8 Self-Referential Integrity 3.3.9 PL/SQL Error Handling with Parent/Child Tables 3.3.10 The Deferrable Option 69 70 Chapter 3 • Declarative Constraints 3.4 CHECK 3.4.1 Multicolumn Constraint 3.4.2 Supplementing Unique Constraints 3.4.3 Students Table Example 3.4.4 Lookup Tables versus Check Constraints 3.4.5 Cardinality 3.4.6 Designing for Check Constraints 3.5 NOT NULL CONSTRAINTS 3.6 DEFAULT VALUES 3.7 MODIFYING CONSTRAINTS 3.8 EXCEPTION HANDLING 3.9 DATA LOADS This is the first of several chapters that cover enforcing business rules with con- straints. -

On Enforcing Relational Constraints in Matbase

Scan to know paper details and author's profile On enforcing relational constraints in MatBase Christian Mancas,Valentina Dorobantu ABSTRACT MatBase is a very powerful database management system based not only on the relational data model, but also on the elementary mathematical, entity-relationship, and Datalog logic ones. This paper briefly introduces MatBase and the elementary mathematical data model, after which is focused on the five relational constraint types and their enforcement in relational database management systems, as well as in MatBase. Keywords: relational data model, domain constraint, not null constraint, unique key constraint, referential integrity constraint, tuple constraint, elementary mathematical data model, MatBase. Classification: H.2.6 H.2 Language: English LJP Copyright ID: 206059 ISBN 10: 1537631683 London ISBN 13: 978-1537631684 LJP Journals Press London Journal of Research in Computer Science and Technology 16UK Volume 17 | Issue 1 | Compilation 1.0 © 2017. Christian Mancas,Valentina Dorobantu. This is a research/review paper, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 Unported License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), permitting all non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) On Enforcing Relational Constraints in MatBase α σ Valentina Dorobantu & Christian Mancas ______________________________________________ I. ABSTRACT 2.1 MatBase MatBase is a very powerful database manage- MatBase [1-5] is a powerful prototype multi- ment system based not only on the relational model, multi-user, and multi-language knowledge data model, but also on the elementary and data (KD) base management system mathematical, entity-relationship, and Datalog (KDBMS) that currently has two versions: one in MS Access 2015 and the other in MS SQL Server logic ones. -

8 the Effectiveness of Test Coverage Criteria for Relational Database Schema Integrity Constraints

The Effectiveness of Test Coverage Criteria for Relational Database Schema Integrity Constraints PHIL MCMINN and CHRIS J. WRIGHT, University of Sheffield GREGORY M. KAPFHAMMER, Allegheny College Despite industry advice to the contrary, there has been little work that has sought to test that a relational database’s schema has correctly specified integrity constraints. These critically important constraints ensure the coherence of data in a database, defending it from manipulations that could violate requirements such as “usernames must be unique” or “the host name cannot be missing or unknown.” This article is the first to propose coverage criteria, derived from logic coverage criteria, that establish different levels of testing for the formulation of integrity constraints in a database schema. These range from simple criteria that mandate the testing of successful and unsuccessful INSERT statements into tables to more advanced criteria that test the formulation of complex integrity constraints such as multi-column PRIMARY KEYs and arbitrary CHECK constraints. Due to different vendor interpretations of the structured query language (SQL) specification with regard to how integrity constraints should actually function in practice, our criteria crucially account for the underlying semantics of the database management system (DBMS). After formally defining these coverage criteria and relating them in a subsumption hierarchy, we present two approaches for automatically generating tests that satisfy the criteria. We then describe the results of an empirical study that uses mutation analysis to investigate the fault-finding capability of data generated when our coverage criteria are applied to a wide variety of relational schemas hosted by three well-known and representative DBMSs— HyperSQL, PostgreSQL, and SQLite. -

Declarative Constraints

5685ch03.qxd_kp 11/6/03 1:36 PM Page 69 THREE Declarative Constraints 3.1 PRIMARY KEY 3.1.1 Creating the Constraint 3.1.2 Naming the Constraint 3.1.3 The Primary Key Index 3.1.4 Sequences 3.1.5 Sequences in Code 3.1.6 Concatenated Primary Key 3.1.7 Extra Indexes with Pseudo Keys 3.1.8 Enable, Disable, and Drop 3.1.9 Deferrable Option 3.1.10 NOVALIDATE 3.1.11 Error Handling in PL/SQL 3.2 UNIQUE 3.2.1 Combining NOT NULL, CHECK with UNIQUE Constraints 3.2.2 Students Table Example 3.2.3 Deferrable and NOVALIDATE Options 3.2.4 Error Handling in PL/SQL 3.3 FOREIGN KEY 3.3.1 Four Types of Errors 3.3.2 Delete Cascade 3.3.3 Mandatory Foreign Key Columns 3.3.4 Referencing the Parent Syntax 3.3.5 Referential Integrity across Schemas and Databases 3.3.6 Multiple Parents and DDL Migration 3.3.7 Many-to-Many Relationships 3.3.8 Self-Referential Integrity 3.3.9 PL/SQL Error Handling with Parent/Child Tables 3.3.10 The Deferrable Option 69 5685ch03.qxd_kp 11/6/03 1:36 PM Page 70 70 Chapter 3 • Declarative Constraints 3.4 CHECK 3.4.1 Multicolumn Constraint 3.4.2 Supplementing Unique Constraints 3.4.3 Students Table Example 3.4.4 Lookup Tables versus Check Constraints 3.4.5 Cardinality 3.4.6 Designing for Check Constraints 3.5 NOT NULL CONSTRAINTS 3.6 DEFAULT VALUES 3.7 MODIFYING CONSTRAINTS 3.8 EXCEPTION HANDLING 3.9 DATA LOADS This is the first of several chapters that cover enforcing business rules with con- straints. -

Relational Data Model and SQL Data Definition Language

The Relational Data Model and SQL Data Definition Language Paul Fodor CSE316: Fundamentals of Software Development Stony Brook University http://www.cs.stonybrook.edu/~cse316 1 The Relational Data Model A particular way of structuring data (using relations) proposed in 1970 by E. F. Codd Mathematically based Expressions ( queries) can be analyzed by DBMS and transformed to equivalent expressions automatically (query optimization) Optimizers have limits (=> the programmer still needs to know how queries are evaluated and optimized) 2 (c) Pearson Education Inc. and Paul Fodor (CS Stony Brook) Relational Databases In Relational DBs, the data is stored in tables Attributes (column Relation name: Student headers) Id Name Address Status 1111 John 123 Main fresh Tuples 2222 Mary 321 Oak (rows) 1234 Bob 444 Pine 9999 Joan 777 Grand senior 3 (c) Pearson Education Inc. and Paul Fodor (CS Stony Brook) Table Set of rows (no duplicates) Each row/tuple describes a different entity Each column/attribute states a particular fact about each entity Each column has an associated domain Id Name Address Status 1111 John 123 Main fresh 2222 Mary 321 Oak 1234 Bob 444 Pine 9999 Joan 777 Grand senior Domain of Id: integers Domain of Name: strings 4 Domain of(c) PearsonStatus Education= Inc.{fresh, and Paul Fodor soph, (CS Stony junior,Brook) senior} Relation A relation is the mathematical entity corresponding to a table: A relation R can be thought of as predicate R A tuple (x,y,z) is in the relation R iff R(x,y,z) is true Why Relations/Tables? Very simple model. -

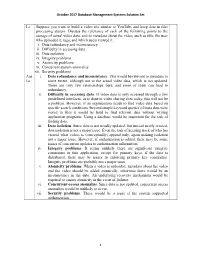

I a Suppose You Want to Build a Video Site Similar to Youtube and Keep Data in File- Processing System. Discuss the Relevance Of

October 2017 Database Management Systems Solution Set I a Suppose you want to build a video site similar to YouTube and keep data in file- processing system. Discuss the relevance of each of the following points to the storage of actual video data, and to metadata about the video, such as title, the user who uploaded it, tags, and which users viewed it. i. Data redundancy and inconsistency ii. Difficulty in accessing data iii. Data isolation iv. Integrity problems v. Atomicity problems vi. Concurrent system anomalies vii. Security problems Ans i. Data redundancy and inconsistency. This would be relevant to metadata to 1a some extent, although not to the actual video data, which is not updated. There are very few relationships here, and none of them can lead to redundancy. ii. Difficulty in accessing data. If video data is only accessed through a few predefined interfaces, as is done in video sharing sites today, this will not be a problem. However, if an organization needs to find video data based on specific search conditions (beyond simple keyword queries) if meta data were stored in files it would be hard to find relevant data without writing application programs. Using a database would be important for the task of finding data. iii. Data isolation. Since data is not usually updated, but instead newly created, data isolation is not a major issue. Even the task of keeping track of who has viewed what videos is (conceptually) append only, again making isolation not a major issue. However, if authorization is added, there may be some issues of concurrent updates to authorization information.