The Problem of Articulation in Stravinsky's Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stravinsky, the Fire-Bird, "The Fire-Bird's Dance,"

/N81 AI2319 Ti VILSKY' USE OF IEhPIAN IN HIS ORCHESTRAL WORKS THE IS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of M1- JiROF JU.SIC by Wayne Griffith, B. Mus. Conway, Arkansas January, 1955 TABLE OF CONTENT4 Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . ,.. , , * . Chap ter I. THE USE OF PIANO1E A' Al ORCTHE TL I:ThUERIMT BEFOR 1910 . , , . , , l STRAICY II. S U6 OF 2E PIANO S E114ORCHES L ORK HIS OF "RUSIA PERIOD . 15 The Fire-Bird Pe~trouchka Le han u hossignol III. STAVIL C ' 0 USE OF TE PI 40IN 9M ORCHESTRAL .RKS OF HIS "NEO-CLASSIO" PERIOD . 56 Symphonyof Psalms Scherzo a la Russe Scenes IBfallet Symphony~in Three Movements BIIORPHYy * - . 100 iii 1I3T OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Berlioz, Leio, Finale, (from Berlioz' Treatise on Instrumentation, p . 157) . 4 2. Saint-Saena, ym phony in 0-minor, (from Prof. H. Kling's Modern Orchestration and Instrumentation, a a.~~~~*f0" 0. 7 p. 74) . 0 0 * * * 3. Moussorgsky, Boris Godunov, "Coronation Scene,'" 36-40 mm.f . -a - - --. " " . 10 4. oussorgsky, Boris Godunov, "Coronation :scene," mm. 241-247 . f . * . 11 5. imsky-Korsakoff, Sadko , (from rimkir -Korsakoff' s Principles of 0rchtiration, Lart II, p. 135) . 12 6. ximsky-Korsakoff, The Snow aiden, (from Zimsky torsatoff'c tTTrin~lecs ofhOrchestration, Part II, . 01) . - - . - . * - - . 12 7 . i s akosy-. o Rf, TVe <now %aiN , (f 0r 1;i s^ky Korsaoif ' s Prciniles of Orchestration, Part II, 'p. 58) . aa. .a. .a- -.-"- -a-a -r . .". 13 8. Stravinsky, The Fire-Bird, "The Fire-Bird's Dance," 9. -

Comparison and Contrast of Performance Practice for the Tuba

COMPARISON AND CONTRAST OF PERFORMANCE PRACTICE OF THE TUBA IN IGOR STRAVINSKY’S THE RITE OF SPRING, DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH’S SYMPHONY NO. 5 IN D MAJOR, OP. 47, AND SERGEI PROKOFIEV’S SYMPHONY NO. 5 IN B FLAT MAJOR, OP. 100 Roy L. Couch, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2006 APPROVED: Donald C. Little, Major Professor Eugene Migliaro Corporon, Minor Professor Keith Johnson, Committee Member Brian Bowman, Coordinator of Brass Instrument Studies Graham Phipps, Program Coordinator of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Couch, Roy L., Comparison and Contrast of Performance Practice for the Tuba in Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 5 in D major, Op. 47, and Sergei Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 5 in B flat major, Op. 100, Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2006, 46 pp.,references, 63 titles. Performance practice is a term familiar to serious musicians. For the performer, this means assimilating and applying all the education and training that has been pursued in a course of study. Performance practice entails many aspects such as development of the craft of performing on the instrument, comprehensive knowledge of pertinent literature, score study and listening to recordings, study of instruments of the period, notation and articulation practices of the time, and issues of tempo and dynamics. The orchestral literature of Eastern Europe, especially Germany and Russia, from the mid-nineteenth century through the mid-twentieth century provides some of the most significant and musically challenging parts for the tuba. -

Igor Stravinsky

Igor Stravinsky Source: http://www.8notes.com/biographies/stravinsky.asp ‘Even during his lifetime, Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) was a legendary figure. His once revolutionary work were modern classics, and he influenced three generations of composers and other artists. Cultural giants like Picasso and T. S. Eliot were his friends. President John F. Kennedy honored him at a White House dinner in his eightieth year. 'Stavinsky was born in Oranienbaum, Russia, near St. Petersburg (Leningrad), grew up in a musical atmosphere, and studied with Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. He had his first important opportunity in 1909, when the impresario Sergei Diaghilev heard his music. Diaghilev was the director of the Russian Ballet, an extremely influential troupe which employed great painters as well as important dances, choreographers, and composers. Diaghilev first asked Stravinsky to orchestrate some piano pieces by Chopin as ballet music and then, in 1910, commissioned an original ballet, The Firebird, which was immensely successful. A year later (1911), Stravinsky's second ballet, Petrushka, was performed, and Stravinsky was hailed as a modern master. When his third ballet, The Rite of Spring (a savage, brutal portrayal of a prehistoric ritual in which a young girl is sacrificed to the god of Spring.), had its premiere in Paris in 1913, a riot erupted in the audience--spectators were shocked and outraged by its pagan primitivism, harsh dissonance, percussiveness, and pounding rhythms--but it too was recognized as a masterpiece and influenced composers all over the world. 'During World War I, Stravinsky sought refuge in Switzerland; after the armistice, he moved to France, his home until the onset of World War II, when he came to the United States. -

DANSES CQNCERTANTES by IGOR STRAVINSKY: an ARRANGEMENT for TWO PIANOS, FOUR HANDS by KEVIN PURRONE, B.M., M.M

DANSES CQNCERTANTES BY IGOR STRAVINSKY: AN ARRANGEMENT FOR TWO PIANOS, FOUR HANDS by KEVIN PURRONE, B.M., M.M. A DISSERTATION IN FINE ARTS Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Accepted August, 1994 t ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to extend my appreciation to Dr. William Westney, not only for the excellent advice he offered during the course of this project, but also for the fine example he set as an artist, scholar and teacher during my years at Texas Tech University. The others on my dissertation committee-Dr. Wayne Hobbs, director of the School of Music, Dr. Kenneth Davis, Dr. Richard Weaver and Dr. Daniel Nathan-were all very helpful in inspiring me to complete this work. Ms. Barbi Dickensheet at the graduate school gave me much positive assistance in the final preparation and layout of the text. My father, Mr. Savino Purrone, as well as my family, were always very supportive. European American Music granted me permission to reprint my arrangement—this was essential, and I am thankful for their help and especially for Ms. Caroline Kane's assistance in this matter. Many other individuals assisted me, sometimes without knowing it. To all I express my heartfelt thanks and appreciation. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii CHAPTER L INTRODUCTION 1 n. GENERAL PRINCIPLES 3 Doubled Notes 3 Articulations 4 Melodic Material 4 Equal Roles 4 Free Redistribution of Parts 5 Practical Considerations 5 Homogeneity of Rhythm 5 Dynamics 6 Tutti GesUires 6 Homogeneity of Texmre 6 Forte-Piano Chords 7 Movement EI: Variation I 7 Conclusion 8 BIBLIOGRAPHY 9 m APPENDIX A. -

Nationalism, Primitivism, & Neoclassicism

Nationalism, Primitivism, & Neoclassicism" Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971)! Biographical sketch:! §" Born in St. Petersburg, Russia.! §" Studied composition with “Mighty Russian Five” composer Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov.! §" Emigrated to Switzerland (1910) and France (1920) before settling in the United States during WW II (1939). ! §" Along with Arnold Schönberg, generally considered the most important composer of the first half or the 20th century.! §" Works generally divided into three style periods:! •" “Russian” Period (c.1907-1918), including “primitivist” works! •" Neoclassical Period (c.1922-1952)! •" Serialist Period (c.1952-1971)! §" Died in New York City in 1971.! Pablo Picasso: Portrait of Igor Stravinsky (1920)! Ballets Russes" History:! §" Founded in 1909 by impresario Serge Diaghilev.! §" The original company was active until Diaghilev’s death in 1929.! §" In addition to choreographing works by established composers (Tschaikowsky, Rimsky- Korsakov, Borodin, Schumann), commissioned important new works by Debussy, Satie, Ravel, Prokofiev, Poulenc, and Stravinsky.! §" Stravinsky composed three of his most famous and important works for the Ballets Russes: L’Oiseau de Feu (Firebird, 1910), Petrouchka (1911), and Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring, 1913).! §" Flamboyant dancer/choreographer Vaclav Nijinsky was an important collaborator during the early years of the troupe.! ! Serge Diaghilev (1872-1929) ! Ballets Russes" Serge Diaghilev and Igor Stravinsky.! Stravinsky with Vaclav Nijinsky as Petrouchka (Paris, 1911).! Ballets -

The Rake's Progress by Igor Stravinsky the Role of Baba

THE RAKE'S PROGRESS BY IGOR STRAVINSKY THE ROLE OF BABA THE TURK By WENDY LOUISE NIELSEN B.Music, The University of Lethbridge, 1984 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF MUSIC in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES SCHOOL OF MUSIC We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 1987 Wendy Louise Nielsen, 1987 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date April II. 11*7 DE-6G/81) UBC School of Music Presents The UBC OPERA THEATRE in IGOR STRAVINSKY'S 3 Act Opera in its WEST COAST PREMIERE Conducted and Directed by French Tickner with the UBC Symphony and Opera Chorus March 24, 25, 27 and 28-UBC Auditorium ^>ii?S 8:00 pm Curtain 1 CAST ANNE TRULOVE ... ... Sharon Acton Joanne Hounsell* TOM RAKEWELl ... Blaine Hendsbee David Shefsiek* FATHER TRULOVE . Paul Nash NICK SHADOW .... James Schiebler BABA THE TURK .. .. Wendy Nielsen MOTHER GOOSE ... Marilyn Gronsdal SELLEM ... Allan Marter KEEPER OF BEDLAM Sean Balderstone The action takes place in Eighteenth Century England - SCENES - Act I. -

Edinburgh International Festival 1962

WRITING ABOUT SHOSTAKOVICH Edinburgh International Festival 1962 Edinburgh Festival 1962 working cover design ay after day, the small, drab figure in the dark suit hunched forward in the front row of the gallery listening tensely. Sometimes he tapped his fingers nervously against his cheek; occasionally he nodded Dhis head rhythmically in time with the music. In the whole of his productive career, remarked Soviet Composer Dmitry Shostakovich, he had “never heard so many of my works performed in so short a period.” Time Music: The Two Dmitrys; September 14, 1962 In 1962 Shostakovich was invited to attend the Edinburgh Festival, Scotland’s annual arts festival and Europe’s largest and most prestigious. An important precursor to this invitation had been the outstanding British premiere in 1960 of the First Cello Concerto – which to an extent had helped focus the British public’s attention on Shostakovich’s evolving repertoire. Week one of the Festival saw performances of the First, Third and Fifth String Quartets; the Cello Concerto and the song-cycle Satires with Galina Vishnevskaya and Rostropovich. 31 DSCH JOURNAL No. 37 – July 2012 Edinburgh International Festival 1962 Rostropovich and Vishnevskaya in Edinburgh Week two heralded performances of the Preludes & Fugues for Piano, arias from Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Sixth, Eighth and Ninth Symphonies, the Third, Fourth, Seventh and Eighth String Quartets and Shostakovich’s orches- tration of Musorgsky’s Khovanschina. Finally in week three the Fourth, Tenth and Twelfth Symphonies were per- formed along with the Violin Concerto (No. 1), the Suite from Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Three Fantastic Dances, the Cello Sonata and From Jewish Folk Poetry. -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No. -

JUNE 27–29, 2013 Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 P.M. 15579Th

06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 23 JUNE 2 7–29, 2013 Two Works by Stravinsky Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 p.m. 15, 579th Concert Friday, June 28, 2013, 8 :00 p.m. 15,580th Concert Saturday, June 29, 2013, 8:00 p.m. 15,58 1st Concert Alan Gilbert , Conductor/Magician Global Sponsor Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director These concerts are sponsored by Yoko Nagae Ceschina. A production created by Giants Are Small Generous support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer The Susan and Elihu Rose Foun - Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer dation, Donna and Marvin Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Schwartz, the Mary and James G. Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Wallach Family Foundation, and an anonymous donor. Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Filming and Digital Media distribution of this Amar Ramasar , Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* production are made possible by the generos ity of The Mary and James G. Wallach Family This concert will last approximately one and Foundation and The Rita E. and Gustave M. three-quarter hours, which includes one intermission. Hauser Recording Fund . Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center Home of the New York Philharmonic June 2013 23 06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 24 New York Philharmonic Two Works by Stravinsky Alan Gilbert, Conductor/Magician Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director A production created by Giants Are Small Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Amar Ramasar, Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* STRAVINSKY Le Baiser de la fée (The Fairy’s Kiss ) (1882–1971) (1928, rev. -

Stravinsky Oedipus

London Symphony Orchestra LSO Live LSO Live captures exceptional performances from the finest musicians using the latest high-density recording technology. The result? Sensational sound quality and definitive interpretations combined with the energy and emotion that you can only experience live in the concert hall. LSO Live lets everyone, everywhere, feel the excitement in the world’s greatest music. For more information visit lso.co.uk LSO Live témoigne de concerts d’exception, donnés par les musiciens les plus remarquables et restitués grâce aux techniques les plus modernes de Stravinsky l’enregistrement haute-définition. La qualité sonore impressionnante entourant ces interprétations d’anthologie se double de l’énergie et de l’émotion que seuls les concerts en direct peuvent offrit. LSO Live permet à chacun, en toute Oedipus Rex circonstance, de vivre cette passion intense au travers des plus grandes oeuvres du répertoire. Pour plus d’informations, rendez vous sur le site lso.co.uk Apollon musagète LSO Live fängt unter Einsatz der neuesten High-Density Aufnahmetechnik außerordentliche Darbietungen der besten Musiker ein. Das Ergebnis? Sir John Eliot Gardiner Sensationelle Klangqualität und maßgebliche Interpretationen, gepaart mit der Energie und Gefühlstiefe, die man nur live im Konzertsaal erleben kann. LSO Live lässt jedermann an der aufregendsten, herrlichsten Musik dieser Welt teilhaben. Wenn Sie mehr erfahren möchten, schauen Sie bei uns Jennifer Johnston herein: lso.co.uk Stuart Skelton Gidon Saks Fanny Ardant LSO0751 Monteverdi Choir London Symphony Orchestra Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) The music is linked by a Speaker, who pretends to explain Oedipus Rex: an opera-oratorio in two acts the plot in the language of the audience, though in fact Oedipus Rex (1927, rev 1948) (1927, rev 1948) Cocteau’s text obscures nearly as much as it clarifies. -

January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM

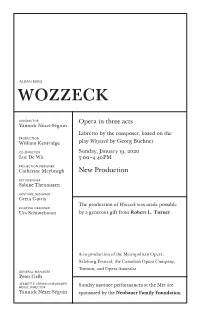

ALBAN BERG wozzeck conductor Opera in three acts Yannick Nézet-Séguin Libretto by the composer, based on the production William Kentridge play Woyzeck by Georg Büchner co-director Sunday, January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM projection designer Catherine Meyburgh New Production set designer Sabine Theunissen costume designer Greta Goiris The production of Wozzeck was made possible lighting designer Urs Schönebaum by a generous gift from Robert L. Turner A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; Salzburg Festival; the Canadian Opera Company, Toronto; and Opera Australia general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Sunday matinee performances at the Met are Yannick Nézet-Séguin sponsored by the Neubauer Family Foundation 2019–20 SEASON The 75th Metropolitan Opera performance of ALBAN BERG’S wozzeck conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin in order of vocal appearance the captain the fool Gerhard Siegel Brenton Ryan wozzeck a soldier Peter Mattei Daniel Clark Smith andres a townsman Andrew Staples Gregory Warren marie marie’s child Elza van den Heever Eliot Flowers margret Tamara Mumford* puppeteers Andrea Fabi the doctor Gwyneth E. Larsen Christian Van Horn ac tors the drum- major Frank Colardo Christopher Ventris Tina Mitchell apprentices Wozzeck is stage piano solo Richard Bernstein presented without Jonathan C. Kelly Miles Mykkanen intermission. Sunday, January 19, 2020, 3:00–4:40PM KEN HOWARD / MET OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Berg’s Wozzeck Video Control Kim Gunning Assistant Video Editor Snezana Marovic Musical Preparation Caren Levine*, Jonathan C. Kelly, Patrick Furrer, Bryan Wagorn*, and Zalman Kelber* Assistant Stage Directors Gregory Keller, Sarah Ina Meyers, and J. -

Summergarden

For Immediate Release July 1990 Summergarden JAZZ-INFLUENCED STRAVINSKY WORKS PERFORMED AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART Friday and Saturday, July 20 and 21, 7:30 p.m. Sculpture Garden open from 6:00 to 10:00 p.m. Seven jazz-influenced works by the Russian composer Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) are presented in the third week of SUMMERGARDEN at The Museum of Modern Art. Made possible by PaineWebber Group Inc., SUMMERGARDEN offers free weekend evenings in the Museum's Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden. The 1990 concert series marks the fourth collaboration between the Museum and The Juilliard School. Paul Zukofsky, artistic director of SUMMERGARDEN, conducts artists of The Juilliard School performing: La Marseillaise (Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle) (1919) Three Pieces (1918) Histoire du soldat (1918) Souvenir d'un marche Boche (1915) Valse pour les enfants (1916-17) Piano-Rag-Music (1919) Septet (1953) Four concerts in the SUMMERGARDEN series are being specially recorded at the Museum for PaineWebber's Traditions, a weekly radio program that is broadcast on Concert Music Network in over thirty major cities across the country. The first New York broadcast is scheduled for July 22 at 9:00 p.m. on WNCN-FM. more - Friday and Saturday evenings in the Sculpture Garden of The Museum of Modern Art are made possible by PaineWebber Group Inc. 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y 10019-5498 Tel: 212-708-9850 Cable: MODERNART Telex: 62370 MODART Telefax: 212-708-9889 2 During SUMMERGARDEN, the Summer Cafe serves light fare and beverages. The Garden is open from 6:00 to 10:00 p.m., and concerts begin at 7:30 p.m.