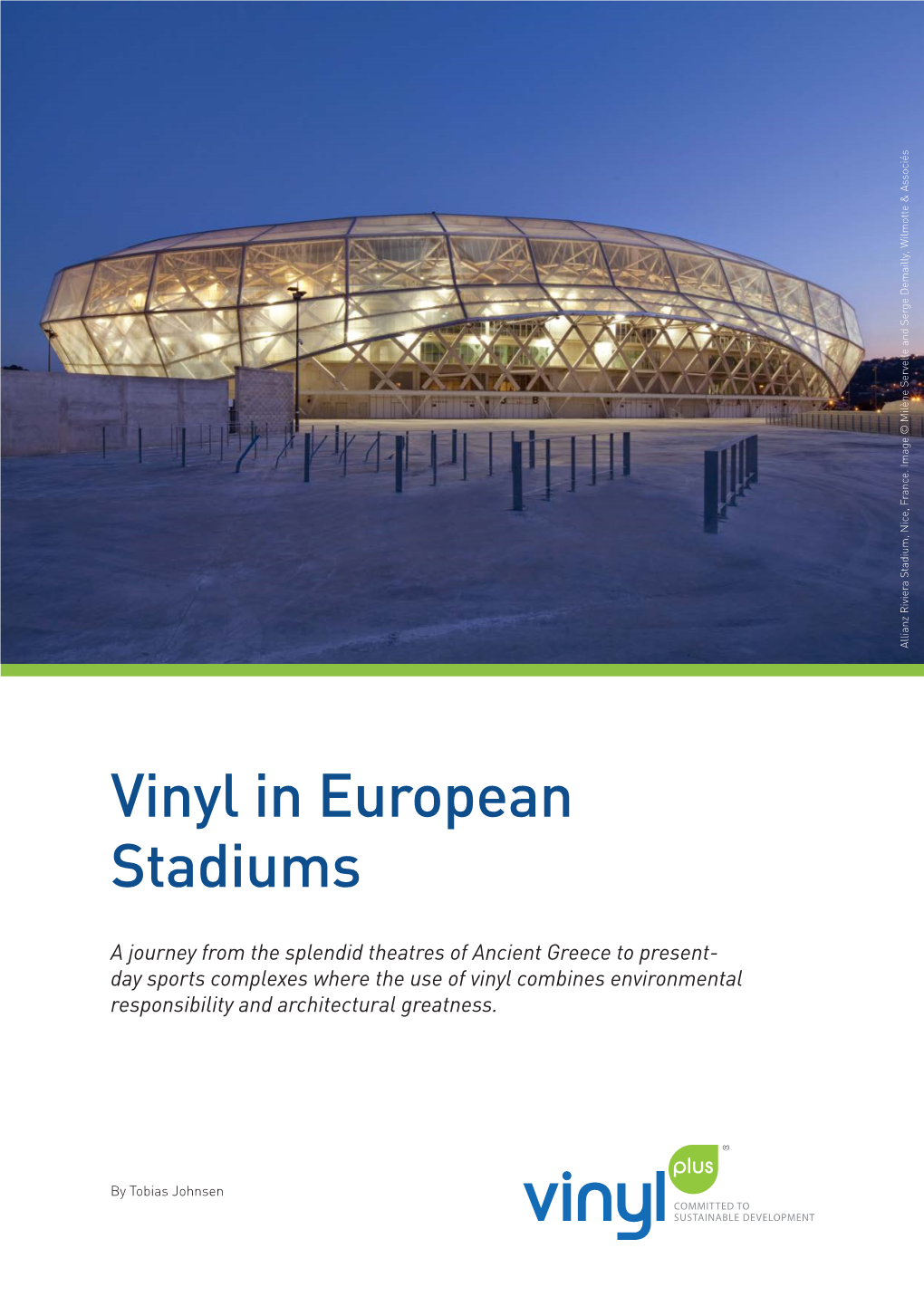

Vinyl in European Stadiums

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Making of the Sainsbury Centre the Making of the Sainsbury Centre

The Making of the Sainsbury Centre The Making of the Sainsbury Centre Edited by Jane Pavitt and Abraham Thomas 2 This publication accompanies the exhibition: Unless otherwise stated, all dates of built projects SUPERSTRUCTURES: The New Architecture refer to their date of completion. 1960–1990 Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts Building credits run in the order of architect followed 24 March–2 September 2018 by structural engineer. First published in Great Britain by Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts Norwich Research Park University of East Anglia Norwich, NR4 7TJ scva.ac.uk © Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, University of East Anglia, 2018 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. A catalogue record is available from the British Library. ISBN 978 0946 009732 Exhibition Curators: Jane Pavitt and Abraham Thomas Book Design: Johnson Design Book Project Editor: Rachel Giles Project Curator: Monserrat Pis Marcos Printed and bound in the UK by Pureprint Group First edition 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Superstructure The Making of the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts Contents Foreword David Sainsbury 9 Superstructures: The New Architecture 1960–1990 12 Jane Pavitt and Abraham Thomas Introduction 13 The making of the Sainsbury Centre 16 The idea of High Tech 20 Three early projects 21 The engineering tradition 24 Technology transfer and the ‘Kit of Parts’ 32 Utopias and megastructures 39 The corporate ideal 46 Conclusion 50 Side-slipping the Seventies Jonathan Glancey 57 Under Construction: Building the Sainsbury Centre 72 Bibliography 110 Acknowledgements 111 Photographic credits 112 6 Fo reword David Sainsbury Opposite. -

On Error at the Buffalo School of Architecture An

Assistant Professor Adjunct James Lowder participated Assistant Professor Adjunct Michael Samuelian discussed Professor Adjunct Michael Webb was a juror for The in The Banham Symposium: On Error at the Buffalo School the volunteer work in the wake of Hurricane Sandy by the Moleskine Grand Central Terminal Sketchbook held in of Architecture and Planning. New Yorkers for Parks, of which he is a group leader, in the partnership with the Architectural League of New York and article “Coney Island Is Still Devastated, From the Boardwalk the New York Transit Museum. He gave a lecture and Visiting Professor Daniel Meridor , as lead creative for to the Neighborhood Parks,” in the New York Observer . In exhibited his drawings in the Stuckeman School of Studio D Meridor +, has continued working on architectural addition to his volunteer work, Samuelian continues his work Architecture and Landscape Architecture at Penn State designs and recently completed several projects including on the urban planning, design and marketing of the Hudson University as part of the 3W seminar. The participants were a presentation for a new awareness-generating infrastructure Yards project in Midtown Manhattan. Hudson Yards broke Michael Webb, Mark West and James Wines and a that links man-made and natural environments, an innovated ground on its first 50 story, $1.5 billion office tower in symposium at the Drawing Center in New York will feature product design for an audio company, and published the December of 2012. He also worked on the development of an them. He gave a lecture at the School of Architecture at essay “Medianeras/Sidewalls: A Film by Gustavo Taretto” exhibition at the AIA Center for Architecture celebrating the the University of Illinois-Chicago and at The Cooper Union in Framework . -

Aqua-Tektur 2

Aqua-Tektur 2 Architecture and Water – Havana 2003 19 architects´ offices and Hansgrohe think ahead . Auer + Weber + Architekten, Munich . Dietz Joppien Architekten, Frankfurt/Main . gmp Architekten von Gerkan, Marg und Partner, Hamburg . Hascher Jehle Architektur, Berlin . RKW Rhode Kellermann Wawrowsky, Düsseldorf . Gewers Kühn und Kühn Architekten, Berlin . Ramseier & Associates Ltd., Zurich . Atelier Werner Schmidt, Trun . UdA Ufficio di Architettura, Turin . Studio Novembre, Milan. ADD+ Arquitectura, Barcelona . Torres & Torres, Barcelona . Alison Brooks Architects, London . Hopkins Architects, London . Jestico + Whiles, London . Hellmuth, Obata + Kassabaum, New York . HLW International, New York . Polshek Partnership Architects, New York . Denton Corker Marshall PTY Ltd., Hongkong Aqua-Tektur Architecture and Water – Havana 2003 19 architects offices and Hansgrohe think ahead . Auer + Weber + Architekten, Munich . Dietz Joppien Architekten, Frankfurt/Main . gmp Architekten von Gerkan, Marg und Partner, Hamburg . Hascher Jehle Architektur, Berlin . RKW Rhode Kellermann Wawrowsky, Düsseldorf .Gewers Kühn und Kühn Architekten, Berlin .Ramseier & Associates Ltd., Zurich .Atelier Werner Schmidt, Trun .UdA ufficio di Architettura, Turin .Studio Novembre, Milan . ADD+ Arquitectura, Barcelona . Torres & Torres, Barcelona . Alison Brooks Architects, London . Hopkins Architects, London . Jestico + Whiles, London . Hellmuth, Obata + Kassabaum, New York . HLW International, New York . Polshek Partnership Architects, New York . Denton Corker -

Portfolio Id

SOM PRIZE AND TRAVEL FELLOWSHIP 2011 PORTFOLIO ID #11 Abstract and Itinerary: SOM 1 Temporary and Transitional Spaces, Architecture and Mobility Itinerary: Background: USA: - Pier Six Concert Pavilion (1991), Baltimore, Maryland, FTL, International Fabric Associated Industries Expo Oct 25-27, 2011 Historically nomadic cultures used lightweight, flexible, and portable materials such as tapestries, animal hides, and thin-wood components to quickly assemble and disassemble communal and - The Smithsonian Institution (2007), Washington, DC, Foster and Partners, Smith Group Inc. private, temporary and transitional spaces. Advancements in technology since 1950 have enhanced the durability and strength of these spaces using plastic and membrane construction methods. - UN Interim Canopy (2009), New York, New York, HLW International, FTL Global events such as the World Cup, The World Expo and The Olympics all require multiple transitional and temporary spaces that support human activities in a safe, sustainable way. Global disasters - The Central Park (2011), San Clemente, California, Michael Maltzan Architects mandate that transitional spaces be quickly assembled with consideration of local, cultural, and economic needs. From airports to temporary event structures, plastic and membrane construction - San Diego Convention Center (1989), San Diego, California, (1989) Arthur Erickson, Horst Berger, Birdair methods continue to set precedents for how architecture can inspire, shelter, and support humanity. By studying precedents and collaborating with -

23.05.06 PE Re Appointment of an Architectural Supremo with Questions

STATEMENT ON A MATTER OF OFFICIAL RESPONSIBILITY The Bailiff: Now we come to a second statement by the Minister for Planning and Environment regarding the appointment of an Architectural Supremo. 8. Senator F.E. Cohen (The Minister for Planning and Environment): It gives me great pleasure to report that I have appointed an Architectural Supremo to advise me on design issues for the Waterfront. I have appointed Hopkins Architects of London, recently voted one of the world’s top 5 most admired architects by his peers. The practice is run by Sir Michael Hopkins. Hopkins Architects have a reputation for creating buildings that combine innovation and popular public appeal often in a sensitive setting. They consistently win major international awards and most notably were awarded the RIBA’s (Royal Institute of British Architects) Royal Gold Medal. Hopkins work across all architectural sectors including master planning in urban regeneration but have become best known for landmark buildings such as Glyndebourne Opera House in Sussex, Portcullis House at Westminster, the Mound stand at Lord’s cricket ground, the Welcome Trust Headquarters and the Aviemore Children’s Hospital. They are also working on several major international projects including a business village in Dubai, campuses at Yale and Princeton Universities and an office, retail and restaurant tower in Tokyo. Sir Michael Hopkins is a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects, the Royal Institute of Architects in Scotland, the Royal College of Art, Nottingham University, London Guild Hall University, University of East Anglia and he is a Royal Academician. He has served as President of the Architectural Association, as a Royal Fine Art Commissioner and as a Member of the London Advisory Committee to English Heritage. -

A R C H I V E

2008A R C H I V E 40under40 Design/Architecture Awards 2008A R C H I V E 28 Butlers Court Sir John Rogersons Quay THE EUROPEAN CENTER Dublin 2 , Ireland FOR ARCHITECTURE ART Phone/Fax: +353 (0)1 670 8781 DESIGN AND URBAN STUDIES E-mail: [email protected] 40under40 Design/Architecture Awards 2008A R C H I V E NIKITA BARINOV RUSSIA Nikita Barinov was born in Kostroma city, Russia and studied at The Academy of architecture in Ivanovo (2006). He lives in Moscow & Kostroma. A R01 C H I V E 01 Dom-Avtonom. Architecture Museum of Yakov Chernikhov. 28 Butlers Court Sir John Rogersons Quay THE EUROPEAN CENTER Dublin 2 , Ireland FOR ARCHITECTURE ART Phone/Fax: +353 (0)1 670 8781 DESIGN AND URBAN STUDIES E-mail: [email protected] www.chi-athenaeum.org 40under40 Design/Architecture Awards 2008A R C H I V E SASA BEGOVIC CROATIA A R C H I V E 02 Riva, Split, Croatia. 02 Sports Hall, Bale, Croatia. 28 Butlers Court Sir John Rogersons Quay THE EUROPEAN CENTER Dublin 2 , Ireland FOR ARCHITECTURE ART Phone/Fax: +353 (0)1 670 8781 DESIGN AND URBAN STUDIES E-mail: [email protected] www.chi-athenaeum.org 40under40 Design/Architecture Awards 2008A R C H I V E MARC BOTINEAU FRANCE A R C H I V E 03 03 Lodgings in Eze South of France 28 Butlers Court Sir John Rogersons Quay THE EUROPEAN CENTER Dublin 2 , Ireland FOR ARCHITECTURE ART Phone/Fax: +353 (0)1 670 8781 DESIGN AND URBAN STUDIES E-mail: [email protected] www.chi-athenaeum.org 40under40 Design/Architecture Awards 2008A R C H I V E CÉCILE BRISAC GREAT BRITAIN Cécile Brisac was born in Firminy, France. -

Sustainable by Design Hopkins Architects Hopkins Hopkins’ “Quest for Architectural Sophistication Dovetails Seamlessly with Superior Environmental Performance”

Sustainable by Design Hopkins Architects Hopkins Hopkins’ “quest for architectural sophistication dovetails seamlessly with superior environmental performance” Hopkins Architects’ commitment to environmentally-advanced design is remarkable and deeply rooted in strategic commitments made more than a decade ago. They are unquestionably pioneers in this increasingly crucial aspect of architecture. In the United States, the practice recently completed the LEED™ ‘Platinum’ rated, Carbon- Neutral Kroon Hall for Yale’s School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. That followed completion of Northern Arizona University’s Advanced Research and Development building, one of the highest-scoring LEED™ ‘Platinum’ buildings in the country. In the United Kingdom in 1996, Hopkins was the first practice to achieve the BREEAM ‘Excellent’ rating for their Inland Revenue Centre. Since then they have designed buildings that already achieve the Government’s 2050 target of 80% cuts in CO2 emissions and are designing to the new highest level of BREEAM, ‘Outstanding.’ Crucially, Hopkins’ approach does not produce repetitive, off-the-shelf environmental design: each building is a specific expression of architectural composition, innovation, function, refined detail, materiality and presence. In every case, and in challenging settings, the quest for architectural sophistication dovetails seamlessly with superior environmental performance - and this ambitious fusion of design and performance has set Hopkins Architects apart. Jay Merrick Architecture Correspondent -

Architecture Prizes, Dec 2020

36 Global Awards 40 National Awards 12 International Regional Awards .. … Prize established RIBA Gold Medal 1848 AIA GoldMedal 1907 The Pritzker Prize 1979 Stirling Prize 1996 Outstanding Structure Award 1998 Carbuncle Cup 2006 ? RIBA Gold Medal Awarded By The Royal Institute of British Architects on behalf of the Queen For Individual's or group's substantial contribution to international architecture Big Name Winners Frank Lloyd Wright 1941 Frank Geary 2000 Zaha Hadid 2016 Latest Winner David Adjaye (Ghana/UK) 2021 Fallingwater: 1935 Frank Lloyd Wright The Dancing House in Prague: 1996 Frank Gehry Heydar Aliyev Centre Baku Architects: Zaha Hadid 2012 Designed for Azerbaijan’s cultural programmes “Breaks from the rigid monumental Soviet architecture and aspires to express the sensibilities of Azeri culture” Moscow School of Management Skolkovo, Moscow, 2010 David Adjaye AIA Gold Medal Awarded By American Institute of Architects For Individuals whose work has had a lasting influence on the theory and practice of Architecture Big Name Winners Edwin Lutyens 1925 Walter Gropius 1959 Le Corbusier 1961 Richard Buckminster Fuller 1970 Latest Winner Marlon Blackwell 2020 Note: Norman Foster sits on the awards jury The Biosphere Environment Museum Montreal Castle Drogo Bauhaus New School Building Dessau UN Building New York St Nicholas Eastern Orthodox Church Architect: Marlon Blackwell 2012 The Pritzker Prize The Pritzker family of Chicago established the Awarded By prize in 1979. It is sponsored by Hyatt Hotels. Reckoned to be the Nobel Prize -

York Academic Village and Conference Center RFQ Project No

York Academic Village and Conference Center RFQ Project No. YC-CUCF-04-09 List of Firms that Downloaded this RFQ Firm Name Address: City: State: Zip Code: First Name: Last Name: Phone: Email: AB Consulting 34 ScandiaRoad Congers NY 10920 Bharat Patel (845) 268-0170 [email protected] Accra Sheetmetal, llc 1359 straight Path wyandanch NY 11798 ORLANDO STOKES 631-643-2100 [email protected] Ahuja Partnership Architects 200 Varick Street Suite 503 New York NY 10014 Hugh Isleib 212-675-5560 [email protected] Albanese Development Corporation 1050 Franklin Avenue Garden City NY 11530 Robert Hanski 516-746-6000 [email protected] Alexander Wolf & Son 211 E 43rd Street New York NY 10017 Peter Bernstein 212-972-1740 [email protected] Allied Works Architecture 12 W 27th Street, 18th Floor New York New York 10001 John Patrick 212.431.9476 [email protected] ANALIESE HOME CORP. 142-15 NEWPORT AVE. ROCKAWAY PARK NEW YORK 11694 JONATHAN OLEARY 212-971-9181 [email protected] Ann Marie Baranowski Architect PLLC (AMBA) 315 West 39th Street #809 New York New York 10018 Ann Marie Baranowski 212 675 7265 [email protected] ARC Networks 221 Central Avenue Farmingdale NY 11735 Michael Connolly 631-227-3106 [email protected] Archi-Tectonics 11 Hubert Street New York NY 10013 Thomas Barry 212-226-0303 [email protected] at architects 50 w. 29th st., 10W new york ny 10001 Ana Maria Torres 212-219-0362 [email protected] Atelier Consulting, LLC 853 Broadway, Suite 800 New Yrk NY 10003 George Villar 888-239-7778 [email protected] Axis Construction Corporation 125 Laser Court Hauppauge New York 11755 Peter Cannuscio 631-243-5970 [email protected] Ayers Saint Gross 1040 Hull Street, Suite 100 Baltimore MD 21230 Jim Wheeler 410-347-8500 [email protected] B. -

Design Competitions Guidance for Clients

Design Competitions Guidance for Clients Royal Institute of British Architects Foreword Design competitions deliver exciting buildings and projects. They drive up quality, stimulate creativity and innovation and generate a range of ideas improving choice. They are a highly successful procurement model that brings out the best in a project – often providing a platform to showcase new and emerging talent. This Guide seeks to give individuals and organisations interested in using a competition essential background information and practical Angela Brady advice on how to plan and run a successful competitive process. RIBA President 2011 - 2013 It aims to cut through the jargon, explain the different competition formats, how they work and the key points to consider. The RIBA has supported the principle of architectural competitions since 1871. As part of its work to improve the quality and sustainability of procurement in the UK, the RIBA is committed to supporting the increased use of well run design competitions. Today, the Institute is the UK’s most widely recognised organisation with the expertise and experience to support the process from initial client idea through to project commission and completion. The work of the RIBA’s dedicated competitions team highlights that the integrity and accountability of a well-run competition, tailored to each individual project, is increasingly important both to clients and competing design teams. If you would like to know more about the RIBA’s services, and how we can help you meet your project aims and aspirations, please get in touch. This guide sets out the RIBA’s best practice standards and I hope you find this guide informative and useful and it helps your project to achieve its full potential. -

Hopkins 3 2 Hopkins 3

Hopkins 3 2 Hopkins 3 Rob Gregory Paul Finch Prestel Munich · London · New York Front cover: Shin-Marunouchi Building Editorial direction: Ali Gitlow Hopkins Architects would like to ©Ken’ichi Suzuki cover, p70, p74, p77, © Ken’ichi Suzuki Editorial assistance: Eve Dawoud acknowledge particularly the p78, p79 Frontispiece: Kroon Hall, Yale University Copyedited by: Matthew Taylor contribution of Senior Partner, Finance, ©Mike Taylor p214 © Morley von Sternberg Production: Friederike Schirge Henry Buxton to all the projects. ©Paul Tyagi p7(tl,tr), p8(tl), p19(b), 21(b), Design and layout: p33, p35, p38, p39, p54, p55, p57(b), © For the text by Rob Gregory Esterson Associates Thanks are extended to Robert Gregory p58/59, p60(t), p61(b), p83(t), p85, p87, and Paul Finch and Paul Finch for their texts, and to p93, p94(t,b), p95, p106, p107, p110(t), Origination: Simon Esterson and Mark Leeds for the p111, p155, p157(t), p158(t), p159(t), p162, © Prestel Verlag, Reproline Mediateam, Munich design and John Hewitt for his drawings p164/165, p168, p169, p171(r), p174, p175, Munich · London · New York 2012 Printing and binding: contribution to this book. p176, p177(t), p178, p180/181 Appl, Wemding ©Morley Von Sternberg p2, p9(tr), p97, The rights of Rob Gregory and Paul Printed in Germany Also to Alet Mans and Nathaniel Moore p99, p101, p102(b), p103(b), p104, p215, Finch to be identifi ed as authors of this for book co-ordination. p218/219, p220(b), p270(t), p271(t), work has been asserted in accordance p208, p209, p211(t), p212(b), p213(t), with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Photography credits p295, p299(t,b), p300/301 Act 1988. -

Continuity and Development in Architecture Transcript

Continuity and Development in Architecture Transcript Date: Thursday, 5 June 2014 - 6:00PM Location: Guildhall 05 June 2014 The Gresham Special Lecture Continuity and Development in Architecture Stephen Hodder MBE President of the Royal Institute of British Architects I am deeply honoured to have been invited to give this year’s Gresham Special lecture. For this I have chosen the subject ‘Continuity and tradition, an exploration of the value and impact of architecture’, using the Stirling Prize as a vehicle for this exploration. But I would like to start with a quotation; ‘Good design builds communities, creates quality of life, and makes places better for people to live, work and play in. I want to make sure we’re doing all we can to recognise the importance of architecture and reap the benefits of good design.’ Ed Vaizey MP, in his foreword to the Farrell review Established in 1996 the RIBA Stirling Prize is awarded to a building that has made the most significant contribution to the advancement of architecture and the built environment in the European Union in a given year. But first a little background. The RIBA Awards have been running annually since 1966, and the Building of the Year since 1993, initially the gift of the President. Buildings are initially entered and assessed regional. Regional award-winning buildings are then considered nationally, from which a shortlist of six national award-winning buildings go on to be considered for the premier prize. It is a most rigorous process with each building being visited by a panel comprising of both architect and lay judges.