Update on Addison's Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Endocrine Drugs

PharmacologyPharmacologyPharmacology DrugsDrugs thatthat AffectAffect thethe EndocrineEndocrine SystemSystem TopicsTopicsTopics •• Pituitary Pituitary DrugsDrugs •• Parathyroid/Thyroid Parathyroid/Thyroid DrugsDrugs •• Adrenal Adrenal DrugsDrugs •• Pancreatic Pancreatic DrugsDrugs •• Reproductive Reproductive DrugsDrugs •• Sexual Sexual BehaviorBehavior DrugsDrugs FunctionsFunctionsFunctions •• Regulation Regulation •• Control Control GlandsGlandsGlands ExocrineExocrine EndocrineEndocrine •• Secrete Secrete enzymesenzymes •• Secrete Secrete hormoneshormones •• Close Close toto organsorgans •• Transport Transport viavia bloodstreambloodstream •• Require Require receptorsreceptors NervousNervous EndocrineEndocrine WiredWired WirelessWireless NeurotransmittersNeurotransmitters HormonesHormones ShortShort DistanceDistance LongLong Distance Distance ClosenessCloseness ReceptorReceptor Specificity Specificity RapidRapid OnsetOnset DelayedDelayed Onset Onset ShortShort DurationDuration ProlongedProlonged Duration Duration RapidRapid ResponseResponse RegulationRegulation MechanismMechanismMechanism ofofof ActionActionAction HypothalamusHypothalamusHypothalamus HypothalamicHypothalamicHypothalamic ControlControlControl PituitaryPituitaryPituitary PosteriorPosteriorPosterior PituitaryPituitaryPituitary Target Actions Oxytocin Uterus ↑ Contraction Mammary ↑ Milk let-down ADH Kidneys ↑ Water reabsorption AnteriorAnteriorAnterior PituitaryPituitaryPituitary Target Action GH Most tissue ↑ Growth TSH Thyroid ↑ TH secretion ACTH Adrenal ↑ Cortisol Cortex -

Frequently Asked Questions for Addison Patients

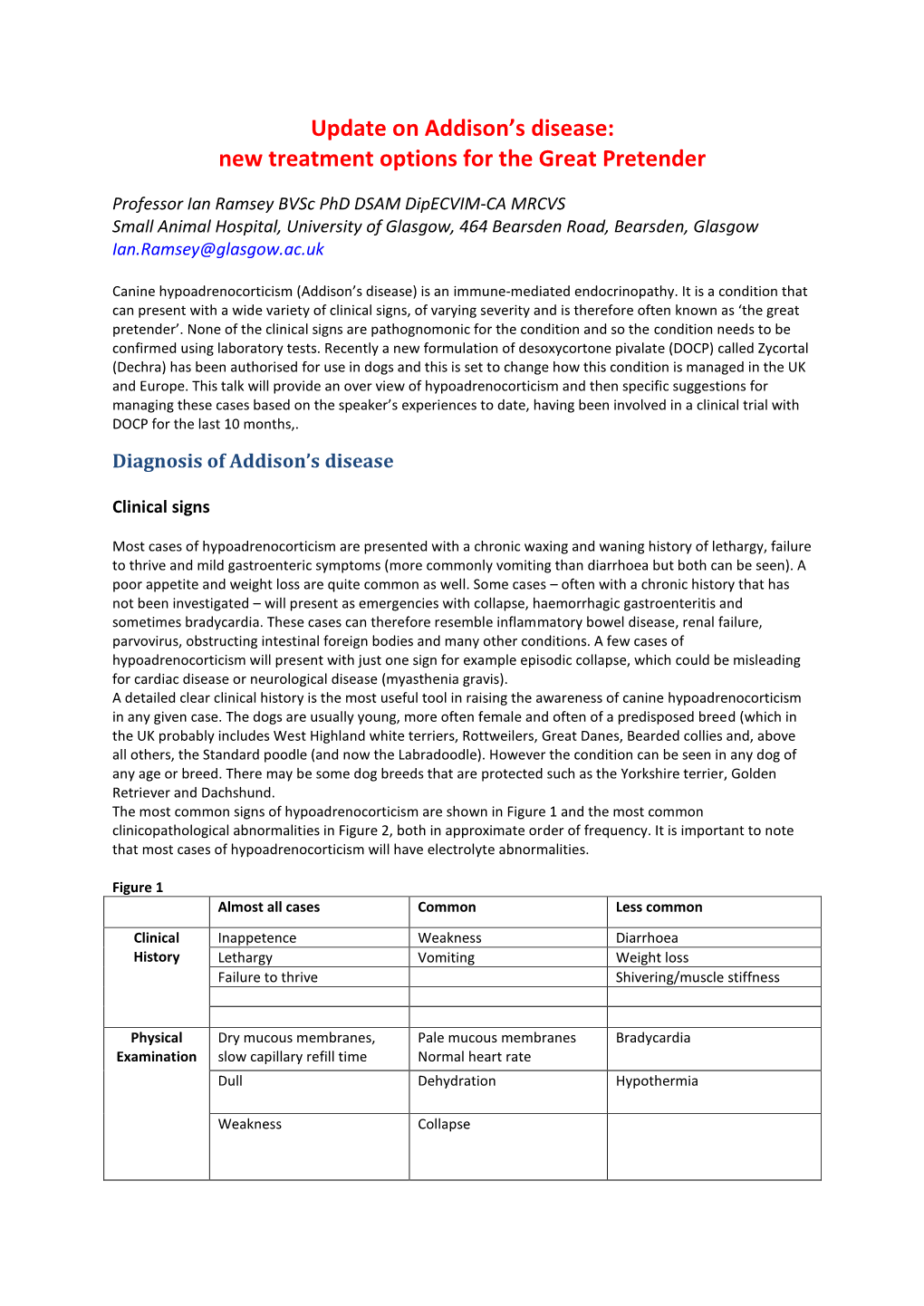

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS FOR ADDISON PATIENTS TABLE OF CONTENT (Place your cursor over the subject line, hold down the Control Button and Click your mouse. To get back to the Table of Content, hold down the Control Button and press the Home key) ADDISONIAN CRISIS / EMERGENCY ADDISONS AND OTHER DISORDERS ADDISONS AND OTHER MEDICATIONS ADRENALINE BLOOD PRESSURE COMMON COLD/FLU/OTHER ILLNESS CORTISOL DAY CURVE CORTISOL MEDICATION CRAMPS DIABETES DIAGNOSING ADDISONS EXERCISE / SPORTS FATIGUE FLORINEF / SALT / SODIUM HERBAL / VITAMIN SUPPLEMENTS HYPERPIGMENTATION IMMUNIZATION MENOPAUSE, PREGNANCY, HORMONE REPLACEMENT, BIRTH CONTROL, HYSTERECTOMY MISCELLANEOUS OSTEOPOROSIS SECONDARY ADDISON’S SHIFT WORK SLEEP 1 STRESS DOSING SURGICAL, MEDICAL, DENTAL PROCEDURES THYROID TRAVEL WEIGHT GAIN 2 ADDISONIAN CRISIS / EMERGENCY How do you know when to call an ambulance? If you are careful, you should not have to call an ambulance. If someone with adrenal insufficiency has gastrointestinal problems and is unable to keep down their cortisol or other glucocorticoid for more than 24 hrs, they should be taken to an emergency department so they can be given intravenous solucortef and saline. It is not appropriate to wait until they are so ill that they cannot be taken to the hospital by a family member. If the individual is unable to retain anything by mouth and is very ill, or if they have had a sudden stress such as a fall or an infection, then it would be necessary for them to go by ambulance as soon as possible. It is important that you should have an emergency kit at home and that someone in the household knows how to use it. -

6. Endocrine System 6.1 - Drugs Used in Diabetes Also See SIGN 116: Management of Diabetes, 2010

1 6. Endocrine System 6.1 - Drugs used in Diabetes Also see SIGN 116: Management of Diabetes, 2010 http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/116 Insulin Prescribing Guidance in Type 2 Diabetes http://www.fifeadtc.scot.nhs.uk/media/6978/insulin-prescribing-in-type-2-diabetes.pdf 6.1.1 Insulins (Type 2 Diabetes) 6.1.1.1 Short Acting Insulins 1st Choice S – Insuman ® Rapid (Human Insulin) S – Humulin S ® S – Actrapid ® 2nd Choice S – Insulin Aspart (NovoRapid ®) (Insulin Analogues) S – Insulin Lispro (Humalog ®) 6.1.1.2 Intermediate and Long Acting Insulins 1st Choice S – Isophane Insulin (Insuman Basal ®) (Human Insulin) S – Isophane Insulin (Humulin I ®) S – Isophane Insulin (Insulatard ®) 2nd Choice S – Insulin Detemir (Levemir ®) (Insulin Analogues) S – Insulin Glargine (Lantus ®) Biphasic Insulins 1st Choice S – Biphasic Isophane (Human Insulin) (Insuman Comb ® ‘15’, ‘25’,’50’) S – Biphasic Isophane (Humulin M3 ®) 2nd Choice S – Biphasic Aspart (Novomix ® 30) (Insulin Analogues) S – Biphasic Lispro (Humalog ® Mix ‘25’ or ‘50’) Prescribing Points For patients with Type 1 diabetes, insulin will be initiated by a diabetes specialist with continuation of prescribing in primary care. Insulin analogues are the preferred insulins for use in Type 1 diabetes. Cartridge formulations of insulin are preferred to alternative formulations Type 2 patients who are newly prescribed insulin should usually be started on NPH isophane insulin, (e.g. Insuman Basal ®, Humulin I ®, Insulatard ®). Long-acting recombinant human insulin analogues (e.g. Levemir ®, Lantus ®) offer no significant clinical advantage for most type 2 patients and are much more expensive. In terms of human insulin. The Insuman ® range is currently the most cost-effective and preferred in new patients. -

Systolic Blood Pressure

Iatrogenic Cushing’s Syndrome secondary to the Combined Oral Contraceptive Pill in a patient with Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia Satish Artham, Yaasir Mamoojee, Simon Ashwell. Department of Diabetes and Endocrinology, The James cook University Hospital, Middlesbrough, UK Introduction: Systolic blood pressure: Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH) is a rare genetic disorder characterised by deficiency of cortisol and/or mineralocorticoid hormones with over production of sex steroids. 21-hydroxylase deficiency is the commonest cause of CAH accounting for 95% of cases1,2. Severe form of classic CAH occurs in 1 in 15,000 livebirths worldwide3,4. The goals of treating 21-hydroxylase deficiency in women is to replace the deficient steroid hormones, to lower the adrenal precursors and sex steroids. Most commonly used regimens are prednisolone once a day or hydrocortisone split into two or three doses. Case: Discussion: A 30 year old women with CAH diagnosed at birth was on replacement with hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone. She was investigated for ongoing diarrhoea Cortisol is the main glucocorticoid hormone, the majority of by the gastroenterologist and was subsequently diagnosed with Irritable Bowel which is circulated bound to Cortisol Binding Globulin (CBG). Syndrome (IBS). She was then started on buscopan and codeine phosphate for Only about 5% of the circulating cortisol is free. Cortisol action symptom relief. However during her menstrual cycle her abdominal symptoms is terminated by conversion into inactive forms by various were not sufficiently controlled. She was thus commenced on Microgynon, enzymes. It is mainly metabolised in the liver. It is reduced, a Combined Oral Contraceptive Pill (COCP). Within a year of initiation she oxidised and hydroxylated, the products of which are made developed cushingoid features, became hypertensive and started gaining weight. -

Us Anti-Doping Agency

2019U.S. ANTI-DOPING AGENCY WALLET CARDEXAMPLES OF PROHIBITED AND PERMITTED SUBSTANCES AND METHODS Effective Jan. 1 – Dec. 31, 2019 CATEGORIES OF SUBSTANCES PROHIBITED AT ALL TIMES (IN AND OUT-OF-COMPETITION) • Non-Approved Substances: investigational drugs and pharmaceuticals with no approval by a governmental regulatory health authority for human therapeutic use. • Anabolic Agents: androstenediol, androstenedione, bolasterone, boldenone, clenbuterol, danazol, desoxymethyltestosterone (madol), dehydrochlormethyltestosterone (DHCMT), Prasterone (dehydroepiandrosterone, DHEA , Intrarosa) and its prohormones, drostanolone, epitestosterone, methasterone, methyl-1-testosterone, methyltestosterone (Covaryx, EEMT, Est Estrogens-methyltest DS, Methitest), nandrolone, oxandrolone, prostanozol, Selective Androgen Receptor Modulators (enobosarm, (ostarine, MK-2866), andarine, LGD-4033, RAD-140). stanozolol, testosterone and its metabolites or isomers (Androgel), THG, tibolone, trenbolone, zeranol, zilpaterol, and similar substances. • Beta-2 Agonists: All selective and non-selective beta-2 agonists, including all optical isomers, are prohibited. Most inhaled beta-2 agonists are prohibited, including arformoterol (Brovana), fenoterol, higenamine (norcoclaurine, Tinospora crispa), indacaterol (Arcapta), levalbuterol (Xopenex), metaproternol (Alupent), orciprenaline, olodaterol (Striverdi), pirbuterol (Maxair), terbutaline (Brethaire), vilanterol (Breo). The only exceptions are albuterol, formoterol, and salmeterol by a metered-dose inhaler when used -

Steroid Use in Prednisone Allergy Abby Shuck, Pharmd Candidate

Steroid Use in Prednisone Allergy Abby Shuck, PharmD candidate 2015 University of Findlay If a patient has an allergy to prednisone and methylprednisolone, what (if any) other corticosteroid can the patient use to avoid an allergic reaction? Corticosteroids very rarely cause allergic reactions in patients that receive them. Since corticosteroids are typically used to treat severe allergic reactions and anaphylaxis, it seems unlikely that these drugs could actually induce an allergic reaction of their own. However, between 0.5-5% of people have reported any sort of reaction to a corticosteroid that they have received.1 Corticosteroids can cause anything from minor skin irritations to full blown anaphylactic shock. Worsening of allergic symptoms during corticosteroid treatment may not always mean that the patient has failed treatment, although it may appear to be so.2,3 There are essentially four classes of corticosteroids: Class A, hydrocortisone-type, Class B, triamcinolone acetonide type, Class C, betamethasone type, and Class D, hydrocortisone-17-butyrate and clobetasone-17-butyrate type. Major* corticosteroids in Class A include cortisone, hydrocortisone, methylprednisolone, prednisolone, and prednisone. Major* corticosteroids in Class B include budesonide, fluocinolone, and triamcinolone. Major* corticosteroids in Class C include beclomethasone and dexamethasone. Finally, major* corticosteroids in Class D include betamethasone, fluticasone, and mometasone.4,5 Class D was later subdivided into Class D1 and D2 depending on the presence or 5,6 absence of a C16 methyl substitution and/or halogenation on C9 of the steroid B-ring. It is often hard to determine what exactly a patient is allergic to if they experience a reaction to a corticosteroid. -

Advice for Patients Who Take Replacement Steroids (Hydrocortisone, Prednisolone, Dexamethasone Or Plenadren) for Pituitary/Adrenal Insufficiency

Advice for patients who take replacement steroids (hydrocortisone, prednisolone, dexamethasone or plenadren) for pituitary/adrenal insufficiency A number of you have been in touch looking for advice relating to the global coronavirus (also known as COVID-19) outbreak. If you are on steroid replacement therapy for pituitary or adrenal disease, or care for someone who is, and you’re worried about coronavirus, we’ve brought together a number of resources that we hope you will find useful. Coronavirus Adrenal Insufficiency Advice for Patients Primary adrenal insufficiency refers to all patients with loss of function of the adrenal itself, mostly either due to autoimmune Addison’s disease, or other causes such as congenital adrenal hyperplasia, bilateral adrenalectomy and adrenoleukodystrophy. The overwhelming majority of primary adrenal insufficiency patients suffer from both glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid deficiency and usually take hydrocortisone (or prednisolone) and fludrocortisone. Our guidance similarly applies to patients with secondary adrenal insufficiency mostly due to pituitary tumours or previous high-dose glucocorticoid treatment. These patients take hydrocortisone for glucocorticoid deficiency As you will be aware it is important for patients with adrenal insufficiency to increase their steroids if unwell as per the usual sick day rules. Please ensure you have sufficient supplies to cover increased doses if you become unwell and an up to date emergency injection of hydrocortisone 100mg. Patients who suffer from a suspected or confirmed infection with coronavirus usually have high fever for many hours of the day, which results in the need for larger than usual steroid doses, so we advise slightly different sick day rules, which are listed below. -

Pharmacology/Therapeutics II Block III Lectures 2013-14

Pharmacology/Therapeutics II Block III Lectures 2013‐14 66. Hypothalamic/pituitary Hormones ‐ Rana 67. Estrogens and Progesterone I ‐ Rana 68. Estrogens and Progesterone II ‐ Rana 69. Androgens ‐ Rana 70. Thyroid/Anti‐Thyroid Drugs – Patel 71. Calcium Metabolism – Patel 72. Adrenocorticosterioids and Antagonists – Clipstone 73. Diabetes Drugs I – Clipstone 74. Diabetes Drugs II ‐ Clipstone Pharmacology & Therapeutics Neuroendocrine Pharmacology: Hypothalamic and Pituitary Hormones, March 20, 2014 Lecture Ajay Rana, Ph.D. Neuroendocrine Pharmacology: Hypothalamic and Pituitary Hormones Date: Thursday, March 20, 2014-8:30 AM Reading Assignment: Katzung, Chapter 37 Key Concepts and Learning Objectives To review the physiology of neuroendocrine regulation To discuss the use neuroendocrine agents for the treatment of representative neuroendocrine disorders: growth hormone deficiency/excess, infertility, hyperprolactinemia Drugs discussed Growth Hormone Deficiency: . Recombinant hGH . Synthetic GHRH, Recombinant IGF-1 Growth Hormone Excess: . Somatostatin analogue . GH receptor antagonist . Dopamine receptor agonist Infertility and other endocrine related disorders: . Human menopausal and recombinant gonadotropins . GnRH agonists as activators . GnRH agonists as inhibitors . GnRH receptor antagonists Hyperprolactinemia: . Dopamine receptor agonists 1 Pharmacology & Therapeutics Neuroendocrine Pharmacology: Hypothalamic and Pituitary Hormones, March 20, 2014 Lecture Ajay Rana, Ph.D. 1. Overview of Neuroendocrine Systems The neuroendocrine -

Application of Prioritization Approaches to Optimize Environmental Monitoring and Testing of Pharmaceuticals

This is a repository copy of Application of prioritization approaches to optimize environmental monitoring and testing of pharmaceuticals. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/130449/ Article: Burns, Emily E orcid.org/0000-0003-4236-6409, Carter, Laura J, Snape, Jason R. et al. (2 more authors) (2018) Application of prioritization approaches to optimize environmental monitoring and testing of pharmaceuticals. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part B: Critical Reviews. pp. 115-141. ISSN 1521-6950 https://doi.org/10.1080/10937404.2018.1465873 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Application of prioritization approaches to optimize environmental monitoring and testing of pharmaceuticals Emily E. Burns,† Laura J. Cater,‡ Jason Snape,§ Jane Thomas-Oates,† Alistair B.A. Boxall*‡ †Chemistry Department, University of York, Heslington, YO10 5DD, United Kingdom ‡Environment Department, University of York, Heslington, YO10 5DD, United Kingdom §AstraZeneca UK, Global Safety, Health and Environment, Macclesfield, SK10 4TG, United Kingdom *Address correspondence to [email protected] Emily E. -

Replacement Therapy for Adrenal Insufficiency

Group 4: Replacement therapy for adrenal insufficiency Frederic Castinetti, Laurence Guignat, Claire Bouvattier, Dinane Samara-Boustani, Yves Reznik To cite this version: Frederic Castinetti, Laurence Guignat, Claire Bouvattier, Dinane Samara-Boustani, Yves Reznik. Group 4: Replacement therapy for adrenal insufficiency . Annales d’Endocrinologie, Elsevier Masson, 2017, 78 (6), pp.525-534. 10.1016/j.ando.2017.10.007. hal-01724179 HAL Id: hal-01724179 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01724179 Submitted on 10 Apr 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Consensus Group 4: Replacement therapy for adrenal insufficiencyଝ Groupe 4 : traitement substitutif de l’insuffisance surrénale Frédéric Castinettia,∗, Laurence Guignatb, Claire Bouvattierc, Dinane Samara-Boustanid, Yves Reznike,f a UMR7286, CNRS, CRN2M, service d’endocrinologie, hôpital La Conception, Aix Marseille université, AP–HM, 13005 Marseille, France b Service d’endocrinologie et maladies métaboliques, hôpital Cochin, CHU Paris Centre, 75014 Paris, France c Service d’endocrinologie -

Interactions with HBV Treatment

www.hep-druginteractions.org Interactions with HBV Treatment Charts revised September 2021. Full information available at www.hep-druginteractions.org Page 1 of 6 Please note that if a drug is not listed it cannot automatically be assumed it is safe to coadminister. ADV, Adefovir; ETV, Entecavir; LAM, Lamivudine; PEG IFN, Peginterferon; RBV, Ribavirin; TBV, Telbivudine; TAF, Tenofovir alafenamide; TDF, Tenofovir-DF. ADV ETV LAM PEG PEG RBV TBV TAF TDF ADV ETV LAM PEG PEG RBV TBV TAF TDF IFN IFN IFN IFN alfa-2a alfa-2b alfa-2a alfa-2b Anaesthetics & Muscle Relaxants Antibacterials (continued) Bupivacaine ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Cloxacillin ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Cisatracurium ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Dapsone ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Isoflurane ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Delamanid ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Ketamine ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Ertapenem ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Nitrous oxide ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Erythromycin ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Propofol ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Ethambutol ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Thiopental ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Flucloxacillin ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Tizanidine ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Gentamicin ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Analgesics Imipenem ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Aceclofenac ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Isoniazid ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Alfentanil ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Levofloxacin ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Aspirin ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Linezolid ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Buprenorphine ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Lymecycline ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Celecoxib ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Meropenem ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Codeine ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ for distribution. for Methenamine ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Dexketoprofen ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Metronidazole ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Dextropropoxyphene ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Moxifloxacin ◆ ◆ ◆ -

X FACT SHEET

Fludrocortisone For the Patient: Fludrocortisone acetate tablets Other names: FLORINEF® • Fludrocortisone (floo droe kor’ ti sone) is a medication that is used to replace steroids that are normally produced by your body. It is often used with other steroids to prevent side effects from certain cancer treatments and to keep your fluid and mineral balance. Fludrocortisone is not the kind of steroid commonly associated with muscle building effects. It is a tablet that you take by mouth. • Tell your doctor if you have ever had an unusual or allergic reaction to fludrocortisone or other steroid before taking fludrocortisone. • It is important to take fludrocortisone exactly as directed by your doctor. Make sure you understand the directions. • You may take fludrocortisone with food or on an empty stomach. Take your fludrocortisone in the morning. This mimics your body’s natural rhythm of steroid production. • If you miss a dose of fludrocortisone, take it as soon as you can if it is within 12 hours of the missed dose. If it is more than 12 hours since your missed dose, skip the missed dose and go back to your usual dosing times. • Do not stop taking fludrocortisone without telling your doctor. Make sure that you always have a supply on hand before you run out. It is likely that your doctor will tell you to continue taking fludrocortisone even after your cancer treatment has stopped. • Other drugs such as phenytoin (DILANTIN®), warfarin (COUMADIN®), rifampin (RIFADIN®), and neostigmine (PROSTIGMIN®) may interact with fludrocortisone. Tell your doctor if you are taking these or any other drugs as you may need extra blood tests or your dose may need to be changed.