Abraham 150 Sophic and Kabbalistic Ideas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life and Contexts Ļ

Chapter 1 Ļ Life and Contexts ļ n a letter that he sent to the Cretan scholar Saul Hako- I hen Ashkenazi a few years prior to his death, Isaac Abar- banel observed that he had written all of his “commen- taries and compilations” after I left my homeland (’eresខ moladeti); for all of the days that I was in the courts and palaces of kings occupied in their service I had no time to study and looked at no book but squandered my days in vanity and years in futile pursuit so that wealth and honor would be mine; yet the wealth was lost by evil adventure and “honor is departed from Israel” [1 Sam. 4:21]. Only after wandering to and fro over the earth from one kingdom to another . did I “seek out the book of the Lord” [Isa. 34:16].1 This personal retrospective, stark even after allowances are made for its imprecision and an autobiographical topos that it reflects,2 alludes to major foci of Abarbanel’s life. He engaged in large-scale commercial and financial en- deavors. He held positions at three leading European courts. He was a broad scholar who authored a multifaceted literary corpus comprising a variety of full- bodied exegetical tomes and theological tracts. And during roughly the last third of his life, in consequence of Spain’s expulsion of its Jews in 1492, his existence was characterized by itinerancy, often in isolation from family and scholarly peers. Situate these themes and their cognates on a wider historical, cultural, and intellectual canvas, and the result is a rich tableau at the center of which stands an ambitious seeker of power, prestige, and wealth who ar- dently cultivated the intellectual life and its vocations as exegete, theologian, and writer. -

2 the Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah 37 I

ISRAEL AND EMPIRE ii ISRAEL AND EMPIRE A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism Leo G. Perdue and Warren Carter Edited by Coleman A. Baker LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY 1 Bloomsbury T&T Clark An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Imprint previously known as T&T Clark 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury, T&T Clark and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the authors. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-0-56705-409-8 PB: 978-0-56724-328-7 ePDF: 978-0-56728-051-0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset by Forthcoming Publications (www.forthpub.com) 1 Contents Abbreviations vii Preface ix Introduction: Empires, Colonies, and Postcolonial Interpretation 1 I. -

The Genealogy of Christ

The Genealogy Of Christ “The book of the genealogy of Jesus Christ, the Son of David, the Son of Abraham…” (Matthew 1:1) © 2020 David Padfield www.padfield.com Scripture taken from the New King James Version. Copyright ©1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. The Genealogy Of Christ Introduction I. The opening words of the New Testament give us the “genealogy of Jesus Christ, the Son of David, the Son of Abraham” (Matt 1:1). A. These words do not stand in isolation—they are the culmination of the entire Old Testament story. B. Matthew claims that Jesus is the descendant of two of the most significant characters in Bible history: Abraham and David. C. While most Bible readers today skip over the genealogy of Christ, Jewish readers in the first century A.D. would find this list to be of great importance. D. The Bible places great emphasis upon the ancestry and genealogy of Jesus Christ (Rom 1:3–4; Heb 7:14). II. The genealogy of Jesus Christ of Nazareth is often neglected, and yet it is of vital importance to those concerned about salvation. A. “Most contemporary Americans cannot give the maiden names of their great grandmothers or the vocations of their great grandfathers. They seemingly pay little interest to their family ancestry. However, it was not so with the Jew. To him, genealogies were most important. Among other things, the birthright, given to the firstborn son, involved a double inheritance, family leadership, vocational opportunities, and land ownership. That is why genealogies were found throughout the Old Testament. -

Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5776 – 5778 2015 – 2018

Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5776 – 5778 2015 – 2018 Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5776-5778 CONTENTS NOTES ....................................................................................................1 DATES OF FESTIVALS .............................................................................2 CALENDAR OF TORAH AND HAFTARAH READINGS 5776-5778 ............3 GLOSSARY ........................................................................................... 29 PERSONAL NOTES ............................................................................... 31 Published by: The Movement for Reform Judaism Sternberg Centre for Judaism 80 East End Road London N3 2SY [email protected] www.reformjudaism.org.uk Copyright © 2015 Movement for Reform Judaism (Version 2) Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5776-5778 Notes: The Calendar of Torah readings follows a triennial cycle whereby in the first year of the cycle the reading is selected from the first part of the parashah, in the second year from the middle, and in the third year from the last part. Alternative selections are offered each shabbat: a shorter reading (around twenty verses) and a longer one (around thirty verses). The readings are a guide and congregations may choose to read more or less from within that part of the parashah. On certain special shabbatot, a special second (or exceptionally, third) scroll reading is read in addition to the week’s portion. Haftarah readings are chosen to parallel key elements in the section of the Torah being read and therefore vary from one year in the triennial cycle to the next. Some of the suggested haftarot are from taken from k’tuvim (Writings) rather than n’vi’ivm (Prophets). When this is the case the appropriate, adapted blessings can be found on page 245 of the MRJ siddur, Seder Ha-t’fillot. This calendar follows the Biblical definition of the length of festivals. -

A Christian Physicist Examines Noah's Flood and Plate Tectonics

A Christian Physicist Examines Noah’s Flood and Plate Tectonics by Steven Ball, Ph.D. September 2003 Dedication I dedicate this work to my friend and colleague Rodric White-Stevens, who delighted in discussing with me the geologic wonders of the Earth and their relevance to Biblical faith. Cover picture courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, copyright free 1 Introduction It seems that no subject stirs the passions of those intending to defend biblical truth more than Noah’s Flood. It is perhaps the one biblical account that appears to conflict with modern science more than any other. Many aspiring Christian apologists have chosen to use this account as a litmus test of whether one accepts the Bible or modern science as true. Before we examine this together, let me clarify that I accept the account of Noah’s Flood as completely true, just as I do the entirety of the Bible. The Bible demonstrates itself to be reliable and remarkably consistent, having numerous interesting participants in various stories through which is interwoven a continuous theme of God’s plan for man’s redemption. Noah’s Flood is one of those stories, revealing to us both God’s judgment of sin and God’s over-riding grace and mercy. It remains a timeless account, for it has much to teach us about a God who never changes. It is one of the most popular Bible stories for children, and the truth be known, for us adults as well. It is rather unfortunate that many dismiss the account as mythical, simply because it seems to be at odds with a scientific view of the earth. -

The Biography of Isaac Leeser

Biographical Sketch of Isaac Leeser University of Pennsylvania Libraries Biographical Sketch of Isaac Leeser by Arthur Kiron, Schottenstein-Jesselson Curator of Judaica Collections Isaac Leeser was born in the village of Neuenkirchen, which at that time was part of the Prussian province of Westphalia, on December 12, 1806. Leeser's father, Uri Lippman (Uri ben Eliezer) was a merchant of limited financial means and educational background. The name "Leeser" is reputed to have been selected for Isaac by his paternal grandfather, Eliezer (i.e., Liezer). Little is known of Leeser's mother, Sara Isaac Cohen, who died when Leeser was eight. Her name only recently came to light when a Dutch descendant, Ms. Helga Becker Leeser, discovered it while doing genealogical research in the Dulmen Stadtarchiv name-taking act of September 22, 1813. Isaac was the second of three children; his one older sister was named Leah Lippman and his younger brother was named Jacob Lippman. Leah married a butcher named Hirsch Elkus who moved the family to the small town of Denekamp, Holland located near the Dutch-German border. Leeser's younger brother Jacob died of smallpox at the age of twenty-five in 1834, one year after emigrating to America. Jacob contracted the disease from his brother Isaac after coming to Philadelphia to care for him. While surviving the disease and the trauma of his brother's death, Leeser' face remained deeply pock-marked, a disfigurement that would cause him great embarrassment throughout his life. Both Jacob and Isaac died bachelors. Leeser received his early education in Dulmen (in Germany), where his family had moved no later than 1812. -

The Book of Genesis in the Qur'an

Word & World 14/2 (1994) Copyright © 1994 by Word & World, Luther Seminary, St. Paul, MN. All rights reserved. page 195 The Book of Genesis in the Qur’an MARK HILLMER Luther Northwestern Theological Seminary, St. Paul, Minnesota The intent of this article is to show the impact of the book of Genesis on the Qur’an and how it used the Genesis material. I write as an outsider to the Islamic religion, as one not committed to the Islamic theologoumenon that the Qur’an is the uncreated speech of God. I share the conclusion that Muhammad heard the biblical material appearing in the Qur’an from Jews and Christians. This is the view of non-Islamic scholars, who differ only as to whether Muhammad is indebted more to Jews or to Christians or to a Jewish-Christian-gnostic pastiche. I find the last view likely.1 Muhammad imbibed, as prophets do, the cultural and religious ideas of his day; he had no direct access to the literary traditions behind these ideas. Three of the suras (chapters) of the Qur’an are named after persons from Genesis: Joseph, Noah, and Abraham. These are representative of how the Genesis material is handled in the Qur’an. The Joseph sura2 presents the Qur’an’s most direct use of the Old Testament, exhibiting by qur’anic standards a remarkable fidelity to the biblical text. The 1Abraham Geiger, Judaism and Islam (1898; reprint, New York, KTAV, 1970); Heinrich Speyer, Die biblischen Erzählungen im Qoran (1930; reprint, Hildesheim: Ohms, 1961); Jacques Jomier, The Bible and the Koran (New York: Desclee, 1964). -

Chart of the Kings of Israel and Judah

The Kings of Israel & Judah Why Study the Kings? Chart of the Kings Questions for Discussion The Heritage of Jesus Host: Alan's Gleanings Alphabetical List of the Kings A Comment about Names God's Message of Salvation Kings of the United Kingdom (c 1025-925 BC) Relationship to God's King Previous King Judgment Saul none did evil Ishbosheth* son (unknown) David none did right Solomon did right in youth, son (AKA Jedidiah) evil in old age * The kingdom was divided during Ishbosheth's reign; David was king over the tribe of Judah. Kings of Judah (c 925-586 BC) Kings of Israel (c 925-721 BC) Relationship to God's Relationship to God's King King Previous King Judgment Previous King Judgment Rehoboam son did evil Abijam Jeroboam servant did evil son did evil (AKA Abijah) Nadab son did evil Baasha none did evil Asa son did right Elah son did evil Zimri captain did evil Omri captain did evil Ahab son did evil Jehoshaphat son did right Ahaziah son did evil Jehoram son did evil (AKA Joram) Jehoram son of Ahab did evil Ahaziah (AKA Joram) (AKA Azariah son did evil or Jehoahaz) Athaliah mother did evil Jehu captain mixed Joash did right in youth, son of Ahaziah Jehoahaz son did evil (AKA Jehoash) evil in old age Joash did right in youth, son did evil Amaziah son (AKA Jehoash) evil in old age Jeroboam II son did evil Zachariah son did evil did evil Uzziah Shallum none son did right (surmised) (AKA Azariah) Menahem none did evil Pekahiah son did evil Jotham son did right Pekah captain did evil Ahaz son did evil Hoshea none did evil Hezekiah son did right Manasseh son did evil Amon son did evil Josiah son did right Jehoahaz son did evil (AKA Shallum) Jehoiakim Assyrian captivity son of Josiah did evil (AKA Eliakim) Jehoiachin (AKA Coniah son did evil or Jeconiah) Zedekiah son of Josiah did evil (AKA Mattaniah) Babylonian captivity Color Code Legend: King did right King did evil Other. -

Community Shiurim/Learning

בס"ד ותלמוד תורה כנגד כולם ..And the study of TORAH is greater than all (Shabbat 127A) SHIUR HERE Listing of SHIURIM for TORAH enrichment in Highland Park / Edison, NJ community (Updated 11-5-2019) WHEN? WHAT? WHO? WHERE? Shabbat (after early Minyan) Parsha of the week Rabbi Weiss Cong. Ohav Emeth Shabbat (after early Minyan) Minchas Chinuch Rabbi Hoffman Cong. Ohr Torah Shabbat (after early Minyan) Megilas Esther Rabbi Silber Cong. Ahavas Achim Shabbat 8:00 AM Parsha/Halacha of the week Rabbi Hakakian Cong. Etz Ahaim Shabbat 8:05 AM Torah Fundamentals Rabbi Feldman Cong. Agudath Israel Shabbat 8:30 AM Mishnah Danny Ravitz memorial Cong. Ohav Emeth Shabbat 8:35 AM Tanya Shiur Rabbi Feldman Cong. Agudath Israel Shabbat 8:35 AM Chumash Rabbi Yehuda Eichenstein Ateres Shlomo Shabbat 2:30 (1 hour later in summer) Mussar Shaar Habitachon Dr. Presby 467 Lincoln Avenue, HP Shabbat 3:00 (1 hour later in summer) Prophets Trei Asar Dr. Presby 467 Lincoln Avenue, HP Shabbat 60 mins before Mincha Nach Rabbi Bassous Cong. Etz Ahaim Shabbat 60 mins before Mincha Talmud Daf Yomi Rabbi Ziegler Crossways @ 5 Price Dr, Ed Shabbat 50 mins before Mincha Talmud Chaggigah Rabbi Luban Cong. Ohr Torah Shabbat 50 mins before Mincha Talmud Daf Yomi Judah Abraham Cong. Ahavas Achim Shabbat 45 mins before Mincha Daf Hashavua Rabbi Jaffe Cong. Ahavas Yisrael Saturday 7:30 Navi Shiur Rabbi Reisman - Simulcast Cong. Ahavas Achim Sunday 7:30 AM Chaburah Shabbat Rabbi Komet Cong. Agudath Israel Sunday 7:50 AM Daf Yomi B’Iyun Topic Rabbi Sauer Cong. -

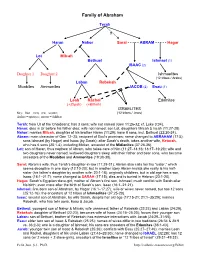

Family of Abraham

Family of Abraham Terah ? Haran Nahor Sarai - - - - - ABRAM - - - - - Hagar Lot Milcah Bethuel Ishmael (1) ISAAC (2) Daughter 1 Daughter 2 Ishmaelites (12 tribes / Arabs) Laban Rebekah Moabites Ammonites JACOB (2) Esau (1) Leah Rachel Edomites (+Zilpah) (+Bilhah) ISRAELITES Key: blue = men; red = women; (12 tribes / Jews) dashes = spouses; arrows = children Terah: from Ur of the Chaldeans; has 3 sons; wife not named (Gen 11:26-32; cf. Luke 3:34). Haran: dies in Ur before his father dies; wife not named; son Lot, daughters Milcah & Iscah (11:27-28). Nahor: marries Milcah, daughter of his brother Haran (11:29); have 8 sons, incl. Bethuel (22:20-24). Abram: main character of Gen 12–25; recipient of God’s promises; name changed to ABRAHAM (17:5); sons Ishmael (by Hagar) and Isaac (by Sarah); after Sarah’s death, takes another wife, Keturah, who has 6 sons (25:1-4), including Midian, ancestor of the Midianites (37:28-36). Lot: son of Haran, thus nephew of Abram, who takes care of him (11:27–14:16; 18:17–19:29); wife and two daughters never named; widowed daughters sleep with their father and bear sons, who become ancestors of the Moabites and Ammonites (19:30-38). Sarai: Abram’s wife, thus Terah’s daughter-in-law (11:29-31); Abram also calls her his “sister,” which seems deceptive in one story (12:10-20); but in another story Abram insists she really is his half- sister (his father’s daughter by another wife; 20:1-18); originally childless, but in old age has a son, Isaac (16:1–21:7); name changed to SARAH (17:15); dies and is buried in Hebron (23:1-20). -

Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5782 – 5784

Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5782 – 5784 2021 – 2024 Notes: The Calendar of Torah readings follows a triennial cycle whereby in the first year of the cycle the reading is selected from the first part of the parashah, in the second year from the middle, and in the third year from the last part. Alternative selections are offered each Shabbat: a shorter reading (around twenty verses) and a longer one (around thirty verses). The readings are a guide and congregations may choose to read more or less from within that part of the parashah. On certain special Shabbatot, a special second (or exceptionally, third) scroll reading is read in addition to the week’s portion. Haftarah readings are chosen to parallel key elements in the section of the Torah being read and therefore vary from one year in the triennial cycle to the next. Some of the suggested haftarot are from taken from k’tuvim (Writings) rather than n’vi’ivm (Prophets). When this is the case the appropriate, adapted blessings can be found on page 245 of the RJ siddur, Seder Ha-t’fillot. This calendar follows the Biblical definition of the length of festivals. Outside Israel, Orthodox communities add a second day to some festivals and this means that for a few weeks their readings may be out of step with Reform/Liberal communities and all those in Israel. The anticipatory blessing for the new month and observance of Rosh Chodesh (with hallel and a second scroll reading) are given for the first day of the Hebrew month. -

Legal Perspectives on the Slaying of Laban

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 1 Number 1 Article 7 7-31-1992 Legal Perspectives on the Slaying of Laban John W. Welch Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Welch, John W. (1992) "Legal Perspectives on the Slaying of Laban," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 1 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol1/iss1/7 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Legal Perspectives on the Slaying of Laban Author(s) John W. Welch Reference Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 1/1 (1992): 119–41. ISSN 1065-9366 (print), 2168-3158 (online) Abstract This article marshals ancient legal evidence to show that Nephi’s slaying of Laban should be understood as a protected manslaughter rather than a criminal homi- cide. The biblical law of murder demanded a higher level of premeditation and hostility than Nephi exhib- ited or modern law requires. The terms of Exodus 21:13, it is argued, protected more than accidental slay- ings or unconscious acts, particularly where God was seen as having delivered the victim into the slayer’s hand. Various rationales for Nephi’s killing of Laban include ancient views on surrendering one person for the benefit of a whole community. Other factors within the Book of Mormon as well as in Moses’ kill- ing of the Egyptian in Exodus 2 corroborate the con- clusion that Nephi did not commit the equivalent of a first-degree murder under the laws of his day.