Codes of Conduct Today Most Free/Libre and Open Source Projects Have Adopted a Code of Conduct1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The GNOME Desktop Environment

The GNOME desktop environment Miguel de Icaza ([email protected]) Instituto de Ciencias Nucleares, UNAM Elliot Lee ([email protected]) Federico Mena ([email protected]) Instituto de Ciencias Nucleares, UNAM Tom Tromey ([email protected]) April 27, 1998 Abstract We present an overview of the free GNU Network Object Model Environment (GNOME). GNOME is a suite of X11 GUI applications that provides joy to users and hackers alike. It has been designed for extensibility and automation by using CORBA and scripting languages throughout the code. GNOME is licensed under the terms of the GNU GPL and the GNU LGPL and has been developed on the Internet by a loosely-coupled team of programmers. 1 Motivation Free operating systems1 are excellent at providing server-class services, and so are often the ideal choice for a server machine. However, the lack of a consistent user interface and of consumer-targeted applications has prevented free operating systems from reaching the vast majority of users — the desktop users. As such, the benefits of free software have only been enjoyed by the technically savvy computer user community. Most users are still locked into proprietary solutions for their desktop environments. By using GNOME, free operating systems will have a complete, user-friendly desktop which will provide users with powerful and easy-to-use graphical applications. Many people have suggested that the cause for the lack of free user-oriented appli- cations is that these do not provide enough excitement to hackers, as opposed to system- level programming. Since most of the GNOME code had to be written by hackers, we kept them happy: the magic recipe here is to design GNOME around an adrenaline response by trying to use exciting models and ideas in the applications. -

Customizing Debian Benjamin Mako Hill

Customizing Debian “Fork Yours with Debian GNU/Linux” Benjamin Mako Hill [email protected] http://mako.yukidoke.org Ubuntu Debian Project Software in the Public Interest Benjamin Mako Hill LCA - Debian MiniConf4 http://mako.yukidoke.org The World of Debian Customizers There are 115 distributions derived from Debian. AbulÉdu • Adamantix • AGNULA GNU/Linux Audio Distribution • ANTEMIUM Linux • Arabbix • ARMA aka Omoikane GNU/Linux • ASLinux • Auditor Security Linux • Augustux • B2D Linux • BEERnix • Biadix • BIG LINUX • Bioknoppix • BlackRhino • Bluewall GNU/Linux • Bonzai Linux • BrlSpeak • Càtix • CensorNet • Clusterix • ClusterKNOPPIX • Condorux • Damn Small Linux • Danix • DebXPde • eduKnoppix • ERPOSS • ESware • Euronode • FAMELIX • Feather Linux • Flonix • Vital Data Forensic or Rescue Kit (FoRK) • Freeduc-cd • GEOLivre Linux • Gibraltar Firewall • GNIX-Vivo • Gnoppix Linux • gnuLinEx • GNU/Linux Kinneret • GNUstep Live CD • grml • Guadalinex • Helix • Hiweed Linux • Impi Linux • Julex • K-DEMar • Kaella • Knoppix Linux Azur • Kalango Linux • KANOTIX • KlusTriX • knopILS • Knoppel • Knoppix • Knoppix 64 • Knoppix STD • KnoppiXMAME • KnoppMyth • Kurumin Linux • LAMPPIX • Libranet GNU/Linux • LIIS Linux • LinEspa • Linspire • Linux Live Game Project • Linux Loco • LinuxDefender Live! CD • Linuxin • LiVux • Local Area Security Linux (L.A.S.) • Luinux • Luit Linux • MAX: Madrid_Linux • Mediainlinux • MEPIS Linux • Metadistro-Pequelin • MIKO GNYO/Linux • Morphix • Munjoy Linux • Nature's Linux • NordisKnoppix • OGo Knoppix • Oralux • Overclockix -

Php Editor Mac Freeware Download

Php editor mac freeware download Davor's PHP Editor (DPHPEdit) is a free PHP IDE (Integrated Development Environment) which allows Project Creation and Management, Editing with. Notepad++ is a free and open source code editor for Windows. It comes with syntax highlighting for many languages including PHP, JavaScript, HTML, and BBEdit costs $, you can also download a free trial version. PHP editor for Mac OS X, Windows, macOS, and Linux features such as the PHP code builder, the PHP code assistant, and the PHP function list tool. Browse, upload, download, rename, and delete files and directories and much more. PHP Editor free download. Get the latest version now. PHP Editor. CodeLite is an open source, free, cross platform IDE specialized in C, C++, PHP and ) programming languages which runs best on all major Platforms (OSX, Windows and Linux). You can Download CodeLite for the following OSs. Aptana Studio (Windows, Linux, Mac OS X) (FREE) Built-in macro language; Plugins can be downloaded and installed from within jEdit using . EditPlus is a text editor, HTML editor, PHP editor and Java editor for Windows. Download For Mac For macOS or later Release notes - Other platforms Atom is a text editor that's modern, approachable, yet hackable to the core—a tool. Komodo Edit is a simple, polyglot editor that provides the basic functionality you need for programming. unit testing, collaboration, or integration with build systems, download Komodo IDE and start your day trial. (x86), Mac OS X. Download your free trial of Zend Studio - the leading PHP Editor for Zend Studio - Mac OS bit fdbbdea, Download. -

Annual Report

[Credits] Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution license (CC BY 4.0). All text by John Hsieh and Georgia Young, except the Letter from the Executive Director, which is by John Sullivan. Images (name, license, and page location): Wouter Velhelst: cover image; Kori Feener, CC BY-SA 4.0: inside front cover, 2-4, 8, 14-15, 20-21, 23-25, 27-29, 32-33, 36, 40-41; Michele Kowal: 5; Anonymous, CC BY 3.0: 7, 16, 17; Ruben Rodriguez, CC BY-SA 4.0: 10, 13, 34-35; Anonymous, All rights reserved: 16 (top left); Pablo Marinero & Cecilia e. Camero, CC BY 3.0: 17; Free This report highlights activities Software Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0: 18-19; Tracey Hughes, CC BY-SA 4.0: 30; Jose Cleto Hernandez Munoz, CC BY-SA 3.0: 31, Pixabay/stevepb, CC0: 37. and detailed financials for Fiscal Year 2016 Fonts: Letter Gothic by Roger Roberson; Orator by John Scheppler; Oswald by (October 1, 2015 - September 30, 2016) Vernon Adams, under the OFL; Seravek by Eric Olson; Jura by Daniel Johnson. Created using Inkscape, GIMP, and PDFsam. Designer: Tammy from Creative Joe. 1] LETTER FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR 2] OUR MISSION 3] TECH 4] CAMPAIGNS 5] LIBREPLANET 2016 6] LICENSING & COMPLIANCE 7] CONFERENCES & EVENTS 7 8] LEADERSHIP & STAFF [CONTENTS] 9] FINANCIALS 9 10] OUR DONORS CONTENTS our most important [1] measure of success is support for the ideals of LETTER FROM free software... THE EXECUTIVE we have momentum DIRECTOR on our side. LETTER FROM THE 2016 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR DEAR SUPPORTERS For almost 32 years, the FSF has inspired people around the Charity Navigator gave the FSF its highest rating — four stars — world to be passionate about computer user freedom as an ethical with an overall score of 99.57/100 and a perfect 100 in the issue, and provided vital tools to make the world a better place. -

Praise for the Official Ubuntu Book

Praise for The Official Ubuntu Book “The Official Ubuntu Book is a great way to get you started with Ubuntu, giving you enough information to be productive without overloading you.” —John Stevenson, DZone Book Reviewer “OUB is one of the best books I’ve seen for beginners.” —Bill Blinn, TechByter Worldwide “This book is the perfect companion for users new to Linux and Ubuntu. It covers the basics in a concise and well-organized manner. General use is covered separately from troubleshooting and error-handling, making the book well-suited both for the beginner as well as the user that needs extended help.” —Thomas Petrucha, Austria Ubuntu User Group “I have recommended this book to several users who I instruct regularly on the use of Ubuntu. All of them have been satisfied with their purchase and have even been able to use it to help them in their journey along the way.” —Chris Crisafulli, Ubuntu LoCo Council, Florida Local Community Team “This text demystifies a very powerful Linux operating system . in just a few weeks of having it, I’ve used it as a quick reference a half dozen times, which saved me the time I would have spent scouring the Ubuntu forums online.” —Darren Frey, Member, Houston Local User Group This page intentionally left blank The Official Ubuntu Book Sixth Edition This page intentionally left blank The Official Ubuntu Book Sixth Edition Benjamin Mako Hill Matthew Helmke Amber Graner Corey Burger With Jonathan Jesse, Kyle Rankin, and Jono Bacon Upper Saddle River, NJ • Boston • Indianapolis • San Francisco New York • Toronto • Montreal • London • Munich • Paris • Madrid Capetown • Sydney • Tokyo • Singapore • Mexico City Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. -

A Brief History of GNOME

A Brief History of GNOME Jonathan Blandford <[email protected]> July 29, 2017 MANCHESTER, UK 2 A Brief History of GNOME 2 Setting the Stage 1984 - 1997 A Brief History of GNOME 3 Setting the stage ● 1984 — X Windows created at MIT ● ● 1985 — GNU Manifesto Early graphics system for ● 1991 — GNU General Public License v2.0 Unix systems ● 1991 — Initial Linux release ● Created by MIT ● 1991 — Era of big projects ● Focused on mechanism, ● 1993 — Distributions appear not policy ● 1995 — Windows 95 released ● Holy Moly! X11 is almost ● 1995 — The GIMP released 35 years old ● 1996 — KDE Announced A Brief History of GNOME 4 twm circa 1995 ● Network Transparency ● Window Managers ● Netscape Navigator ● Toolkits (aw, motif) ● Simple apps ● Virtual Desktops / Workspaces A Brief History of GNOME 5 Setting the stage ● 1984 — X Windows created at MIT ● 1985 — GNU Manifesto ● Founded by Richard Stallman ● ● 1991 — GNU General Public License v2.0 Our fundamental Freedoms: ○ Freedom to run ● 1991 — Initial Linux release ○ Freedom to study ● 1991 — Era of big projects ○ Freedom to redistribute ○ Freedom to modify and ● 1993 — Distributions appear improve ● 1995 — Windows 95 released ● Also, a set of compilers, ● 1995 — The GIMP released userspace tools, editors, etc. ● 1996 — KDE Announced This was an overtly political movement and act A Brief History of GNOME 6 Setting the stage ● 1984 — X Windows created at MIT “The licenses for most software are ● 1985 — GNU Manifesto designed to take away your freedom to ● 1991 — GNU General Public License share and change it. By contrast, the v2.0 GNU General Public License is intended to guarantee your freedom to share and ● 1991 — Initial Linux release change free software--to make sure the ● 1991 — Era of big projects software is free for all its users. -

This Is a Free, User-Editable, Open Source Software Manual. Table of Contents About Inkscape

This is a free, user-editable, open source software manual. Table of Contents About Inkscape....................................................................................................................................................1 About SVG...........................................................................................................................................................2 Objectives of the SVG Format.................................................................................................................2 The Current State of SVG Software........................................................................................................2 Inkscape Interface...............................................................................................................................................3 The Menu.................................................................................................................................................3 The Commands Bar.................................................................................................................................3 The Toolbox and Tool Controls Bar........................................................................................................4 The Canvas...............................................................................................................................................4 Rulers......................................................................................................................................................5 -

(Part B): Feminism As Jurisgenerative Transformation, Or Resistance Through Partial Incorporation? Part I

Schulich School of Law, Dalhousie University Schulich Law Scholars Articles, Book Chapters, & Blogs Faculty Scholarship 1990 Nomos and Thanatos (Part B): Feminism as Jurisgenerative Transformation, or Resistance Through Partial Incorporation? Part I Richard F. Devlin FRSC Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.schulichlaw.dal.ca/scholarly_works Part of the Law and Gender Commons, and the Law and Philosophy Commons Richard F. Devlin* Nomos and Thanatos (Part B). Feminism as Jurisgenerative Transformation, or Resistance Through Partial Incorporation? OUTLINE I) Introduction II) Feminism 1) The Significance of Feminism 2) Themes of Feminism a) The Equality Approach b) The Gynocentric Approach i) Differenceand Literary Criticism a) Trespassers on the Lawns of Patriarchy b) The Cartographiesof Silence i) The New French Feminisms ii) Helene Cixous iii) Julia Kristeva iv) The Significanceof the N.F.F. ii) A DifferentJurisprudence a) Making it Otherwise b) Transcending Bipolarism iii) The Ethic of Care c) Equality Revisited i) MacKinnon's Response to Difference ii) Reflections on MacKinnon a) MacKinnon on Power b) MacKinnon's Positive Vision Equality c) Reconciling MacKinnon and Gilligan d) AlternativeLocations forthe Ethic of Care e) Beyond Either/Or III) Pornography 1) Introduction 2) A Feminist Critique of Pornography ' ' 3) Feminist Responses to Pornography IV) Feminism and the Tum to Law: Part of the Problem, Part of the Solution V) Conclusion I *Richard F. Devlin, Assistant Professor of Law, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta. 124 The Dalhousie Law Journal I. Introduction 1 In Part A of this essay, "The Killing Fields" , I developed a critique of the disciplinary impulses that underlie modern law and legal theory. -

THE BEAUTIFUL WARRIORS Technofeminist Praxis in the Twenty-First Century

Minor Compositions Open Access Statement – Please Read This book is open access. This work is not simply an electronic book; it is the open access version of a work that exists in a number of forms, the traditional printed form being one of them. All Minor Compositions publications are placed for free, in their entirety, on the web. This is because the free and autonomous sharing of knowledges and experiences is important, especially at a time when the restructuring and increased centralization of book distribution makes it difficult (and expensive) to distribute radical texts effectively. The free posting of these texts does not mean that the necessary energy and labor to produce them is no longer there. One can think of buying physical copies not as the purchase of commodities, but as a form of support or solidarity for an approach to knowledge production and engaged research (particularly when purchasing directly from the publisher). The open access nature of this publication means that you can: • read and store this document free of charge • distribute it for personal use free of charge • print sections of the work for personal use • read or perform parts of the work in a context where no financial transactions take place However, it is against the purposes of Minor Compositions open access approach to: • gain financially from the work • sell the work or seek monies in relation to the distribution of the work • use the work in any commercial activity of any kind • profit a third party indirectly via use or distribution of the work • distribute in or through a commercial body (with the exception of academic usage within educational institutions) The intent of Minor Compositions as a project is that any surpluses generated from the use of collectively produced literature are intended to return to further the development and production of further publications and writing: that which comes from the commons will be used to keep cultivating those commons. -

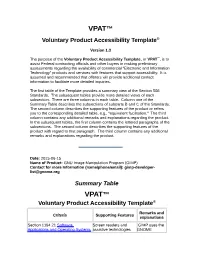

ITI: Voluntary Product Accessibility Template

VPAT™ Voluntary Product Accessibility Template® Version 1.3 The purpose of the Voluntary Product Accessibility Template, or VPAT™, is to assist Federal contracting officials and other buyers in making preliminary assessments regarding the availability of commercial “Electronic and Information Technology” products and services with features that support accessibility. It is assumed and recommended that offerers will provide additional contact information to facilitate more detailed inquiries. The first table of the Template provides a summary view of the Section 508 Standards. The subsequent tables provide more detailed views of each subsection. There are three columns in each table. Column one of the Summary Table describes the subsections of subparts B and C of the Standards. The second column describes the supporting features of the product or refers you to the corresponding detailed table, e.g., “equivalent facilitation." The third column contains any additional remarks and explanations regarding the product. In the subsequent tables, the first column contains the lettered paragraphs of the subsections. The second column describes the supporting features of the product with regard to that paragraph. The third column contains any additional remarks and explanations regarding the product. Date: 2015-06-15 Name of Product: GNU Image Manipulation Program (GIMP) Contact for more Information (name/phone/email): gimp-developer- [email protected] Summary Table VPAT™ Voluntary Product Accessibility Template® Remarks and Criteria Supporting Features explanations Section 1194.21 Software Screen readers and GIMP uses the Applications and Operating Systems assistive technologies GNOME such as on-screen Accessibility keyboards and alternate Toolkit API to pointing devices are provide access supported and to screen configurable e.g. -

ESIG Labs GIMP Smartscissors Tutorial • This Tutorial Will Guide You

ESIG Labs GIMP SmartScissors Tutorial pg. 1 • This tutorial will guide you through the process of “cutting” an object out of a picture, for the purpose of using it on another background or image. -- To begin, we will use the image to the left. -- Our goal will be to “cut” the foreground watermelon out of the photograph, and paste it into another image. • To begin, select the image to the left and press CTRL+C on your keyboard. • Launch GIMP. • Click File New -- The image size does not matter much here; the only goal is to keep the canvas from getting too small for the image. Thus, we will use the generic size of 1000x1000 pixels. Enter “1000” in the “Width” field as well as the “Height” field, and click “OK”. -- Click anywhere in the white space you have just created, and press CTRL+V on your keyboard. –Activate the “Move” tool by pressing “M” on your keyboard. -- Click anywhere in the white space to “Anchor” the image. • Now, click Tools Selection Tools Intelligent Scissors. -- As shown in the graphic (below), work your way around the object by clicking along the object boundary- smart scissors should follow the outline. If it does not simply click and drag boundary line to modify. NOTE: If you need to modify your zoom level at any point, simply press the “Z” button on your keyboard, and click the image to zoom in. To zoom out, CTRL+Click. -- When you are done, click on the first point you have made to “finalize” the boundary, and then click anywhere within the boundary. -

WOMEN SUPERINTENDENTS, the FEMINIST ETHIC, and ORGANIZATIONAL LEADERSHIP a Dissertation Submitted to the Kent State University

WOMEN SUPERINTENDENTS, THE FEMINIST ETHIC, AND ORGANIZATIONAL LEADERSHIP A dissertation submitted to the Kent State University College of Education, Health, and Human Services in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Carol L. Winter December 2016 © 2016, Copyright by Carol L. Winter All Rights Reserved ii A dissertation written by Carol L. Winter B.S., Central Michigan University, 1984 M.A., Eastern Michigan University, 1991 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by _____________________________, Director, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Catherine Hackney _____________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Rosemary Gornik _____________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Jennifer Kulics Accepted by _____________________________, Director, School of Foundations, Leadership and Kimberly S. Schimmel Administration _____________________________, Interim Dean, College of Education, Health and Mark A. Kretovics Human Services iii WINTER, CAROL L., Ph.D., December 2016 EDUCATION ADMINISTRATION WOMEN SUPERINTENDENTS, THE FEMINIST ETHIC, AND ORGANIZATIONAL LEADERSHIP (270 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Catherine Hackney, Ph.D. This qualitative study investigated the research question: How does the feminist ethic interact with the leadership of women superintendents as they address the demands of leading in the current educational climate? Data generated from six participants’ interviews, journal entries, and writing samples were used to formulate a leadership