Dissidence and Conformism in Religious Movements: What Difference – If Any - Separates the Catholic Charismatic Renewal and Pentecostal Churches?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Summer Issue

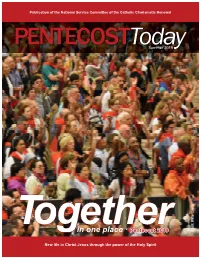

Publication of the National Service Committee of the Catholic Charismatic Renewal PENTECOSTToday Summer 2019 in one place · Pentecost 2019 fromPhoto CHARIS New life in Christ Jesus through the power of the Holy Spirit Chairman’s Editor’s Corner Desk . by Ron Riggins by Sr. Mary Anne Schaenzer, SSND in the unity of those who believe in Christ (Eph 4:11-16). hen I read the word “sandals” in In Pursuit of Unity Ron Riggins’ article concerning the CHARIS captures the unity preached Winauguration of CHARIS, and sandals esus prayed for our unity: “that they by Jesus and later by St. Paul, as Pope spiritually symbolizing readiness to serve, I may all be one” (Jn 17:20-21). And Francis sees baptism in the Holy Spirit recalled a quote regarding sandals: “Put Jin the Nicene Creed we profess as an opportunity for the whole Church. them on and wear them like they fi t.” Or as our belief that the Church is one. He expects those of us who have ex- Ron calls the NSC, Boots on the Ground. The motto in Alexandre Dumas’ novel perienced this current of grace to work CHARIS (Catholic Charismatic Renewal The Three Musketeers reflected a commit- together, using our diverse gifts, for International Service) inaugurated by Pope ment to unity: un pour tous, tous pour un unity in the Renewal and ecumenically Francis, is “marked by communion between (“one for all, all for one”). But then in the Body of Christ for the benefit of all the members of the charismatic family, in Frank Sinatra sang what seems to be the whole Church. -

Living Bulwark

Living Bulwark October / November 2017 - Vol. 94 Love, Unity, and Mission Together “All will know that you are my disciples if you have love for one another”–John13:35 . • Intro to This Issue: Christ Sets Us Free to Love and Serve • Mission, Life Together, and the Second Commandment, by Bob Tedesco • Cooperative Ecumenism: Being Different Without Being Distant, by Mark Kinzer • Love of the Brethren: Among Christians of Different Traditions, by Steve Clark • Through Love Be Servants of One Another, by Don Schwager • 500th Reformation Anniversary, and Five Ecumenical Imperatives • Grace Abounding – Rediscovering the Graciousness of God, by Alister McGrath • Luther, Grace, and Ecumenical Cooperation Today, by Benedict XVI • Christian Disunity, by Christopher Dawson, & Steps to Renewal, by J.I. Packer • Kairos Mission Year in Belfast, and Kairos Gap Year, Video Presentations . • The Lois Project for Christian Moms & Mentors, by Amy Hughes • A Secret Treasure, by Stephanie Smith • Enemy of Full Life in God, and Living Your Hidden Life Well, by Tom Caballes • A God-Centered Approach to Time Management, by Elizabeth Grace Saunders • Gaining God's Perspective on Work& Discerning Work Life Direction, by Joe Firn • On Holiday – The Place to Be with Brothers and Sisters, by Bob Bell • Bethany Association Report, by Marcela Pérez • Interview with Bruce Yocum on 50th Charismatic Renewal Celebration • Bringing God Our Emptiness, by Sam Williamson • A Mighty fortress Is Our God and Thy Mercy Free, hymns by Martin Luther • The Life of Christ Illustrated by James Tissot Living Bulwark is committed to fostering renewal of the whole Christian people: Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox. -

Living Bulwark

Living Bulwark April / May 2019 - Vol. 103 A Living Bulwark of Disciples on Mission “I am writing so that you may know how to conduct yourself in the household of God, which is the church of the living God, the pillar and bulwark of the truth” – 1 Timothy 3:15 • In This Issue: Being a Bulwark that Serves God's Purposes • On Mission: Being a Bulwark, and Part 2: A Life that Wants to Share Itself, by Steve Clark • “Reading the Signs of the Times,” by Bruce Yocum and Bernard Stock • Living Stones, by Dan Keating, and Taking Our Place in the Bulwark, by Bob Tedesco • Unity and Growth: Study on Ephesians 4, by Derek Prince • Born into a Battle: Living a Christian Way of Life in a Secular Society, by Jerry Munk • The Attack on God's Word – And the Response, by Ralph Martin • The Gospel of the Kingdom and Liberating the Captives, by Michael Harper • Love Stronger Than Death:21 Coptic Martyrs & A Mighty Fortress Is Our God,by Martin Luther • Young Professionals on Mission, by Mike Shaughnessy • The Eternal Weight of Glory Awaits, by Tom Caballes • Rewiring My Fears, and Meeting Jesus in Mystery, by Sam Williamson • Can Beauty Change the World? A reflection by Maria from The Lovely Commission • A Spiritual Journey of Poems for Passiontide and Easter, | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | by Jeanne Kun • The Son of God Goes forth to War, sung by Will Cannon • The Incarnate, Crucified, and Risen Lord: Reflections on Christ's Victory Over Sin and Death • Let There Be Light: Part 3 – Orange, Yellow, Green, On Art, Nature, & Christ, by Ros Yates Living Bulwark is committed to fostering renewal of the whole Christian people: Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox. -

Living Bulwark

Living Bulwark December 2015 - January 2016 - Vol. 83 The Day Draws Near “Let us encourage one another to love and good deeds” – Heb. 10:24-25 . • In This Issue: The Day Draws Near • Homeward Bound - But Where Are We Headed? by James Munk • Missing the Point, by Bob Tedesco • Living in the Last Days: A Commentary on 1 Peter 4:7-11, by Dr. Daniel Keating • The True God Whom We Serve, by Carlos Mantica • Living Together as an Ecumenical People in the Sword of the Spirit • The Work of Christ – A Long-standing Ecumenical Community, by Jerry Munk • Observing the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity, by Dave Hughes • Called to Proclaim the Mighty Works of the Lord – Prayers for Christian Unity . • “I Can Start Anew Through the Love of Jesus,” by Rebecca Hanssen • Fresh Beginnings – Amazing Grace, and Looking for Daniel, by Rob Clarke • Kingdom Builders on the Move – Youth Mission Trip • Empty Empathy, by Michael Shaughnessy • “I Came to Cast Fire On the Earth,” European CCR Conference, by D.Schwager • When God Does Not Seem to Answer Your Prayers, by Tom Caballas • Squeezing Bad News from Good News, and Hearing God, by Sam Williamson • Home – Our Abiding Place, and Anna’s Heir, by Jeanne Kun • "The Day Draws Near" – Reflections for the Advent and Christmas Season • From the Manger to the Cross,by Bonhoeffer, & Showing Forth of Christ,byDonne • What the Incarnation Means for Us, by Steve Clark • The River Flows, song and reflection by Ed Conlin Living Bulwark is committed to fostering renewal of the whole Christian people: Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox. -

THE SWORD of the SPIRIT May Yourjoy Be Complete

The Sword of The Spirit February 2013 Saint Paul’s Church www.saintpaulsbrookfield.com (203) 775-9587 May YourJoy Be Complete Transforming Lives Through Jesus Why Are They Always Smiling? I have told you this so that my joy may be in you and that your joy may be complete (John 15:11) hile I was just beginning my freshman year in college, a fraternity brother of mine Vol. LIX-No. 2 shared that he had just joined “Campus Crusade for Christ.” As a nominal W The Sword of the Episcopalian, I was, well, not sure what to think. Perhaps I should have showed open disdain Spirit was started to guarantee that I would be left alone by this group, for my fair-mindedness and nods of polite in 1954 by the Rev. A. Pierce Middleton affirmation (translated, “that’s great for you, but for me, no thanks”) soon gave way to a group of “Crusaders” periodically showing up at my door, waving to me from across the quad and endlessly inviting me to their prayer gatherings. I never showed up to these gatherings, but the one thing I kept wondering, in addition to why they wouldn’t leave me alone, was why they were always smiling? Two years into college, I had a conversion experience directly from God as I was walking down the street. I had no idea what to do, as I knew next to nothing about Christianity. I proceeded to go through my book collection (yes, this was before the Internet, kids) in search of something that might make sense of what had just happened to me. -

Living Bulwark

Living Bulwark June / Julyy 2015 - Vol. 80 Baptized in the Holy Spirit “He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and with fire” – Luke 3:16 • In This Issue: Why God Wants Every Christian to Be Filled with the Holy Spirit • The Century of the Holy Spirit, by Dr. Vinson Synan • The Magnificent Stranger, by Carlos Mantica • Baptized in the Holy Spirit, by Steve Clark • The Baptism in the Spirit - A Grace for the Whole Church, by R. Cantalamessa • The Role of the Holy Spirit in Proclaiming the Gospel Message, by Sue Cummins • Amazing Grace At Work, by Jean Barbara, and Sword of the Spirit Communities • Community Growth: updates from Spirit of Christ, Triumph of the Cross & Seattle . • Empowering a Generation in Mission,& YouthWorks-Detroit Celebrates 20 Years • Transition Fail, & Is Christian Youth Culture Possible? by Michael Shaughnessy • Carpe Diem: Seizing the Moments in Your Life, by Tom Caballes • Hearing God in Reflection & Hearing God in Our Inner Being, by Sam Williamson • The Fire of the Holy Spirit, and The Gift of Tongues, by Don Schwager • Exercising the Prophetic Gifts: Forms of Prophecy, by Bruce Yocum • The Spirit Keeps Us in Perfect Peaceby John Henry Newman & Come, Holy Spirit • Have the Gifts Ceased? & Preparing Children for a Spirit-filled Life, by Jerry Munk • Sweet Manna from the Son’s Heart, verse by Edith Stein • Godly Hobbits: The Pentecostalism of Tolkien’s Inspired Heroes, by Lance Nixon Living Bulwark is committed to fostering renewal of the whole Christian people: Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox. We especially want to give witness to the charismatic, ecumenical, evangelistic, and community dimensions of that renewal. -

An Overview of Pentecostalism a Study of Religions Beliefs

Lesson 5 –An Overview of Pentecostalism A Study of Religions Beliefs www.aubeacon.com Introduction: The growth of the Pentecostal movement in this country has been extraordinary. A. What do we mean by the “Pentecostal Movement?” Pentecostalism is a movement within Christianity that places special emphasis on a direct personal experience of God through the baptism in the Holy Spirit. The term Pentecostal is derived from Pentecost, a Greek term describing the Jewish Feast of Weeks. For Christians, this event commemorates the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the followers of Jesus Christ, as described in the second chapter of the Book of Acts. Pentecostals tend to see their movement as reflecting the same kind of spiritual power, worship styles and teachings that were found in the early church. For this reason, some Pentecostals also use the term Apostolic or full gospel to describe their movement. – Wikipedia B. This movement gives great emphasis to speaking in tongues, healing through miracles, the direct leading of the Holy Spirit and Holy Spirit baptism. 1. While these are Bible subjects and can be examined through Bible study, the Pentecostal Movement mirrows Mormonism in giving priority to personal feelings and experience over anything found through a reasoned study of scripture. 2. There are numerous divisions within this movement. 3. As with any broad movements like this it is important to let the individual you are working with explain their own beliefs. The real challenge is in finding a common ground upon which to study! I. What is the work of theHoly Spirit? A. Jesus plainly stated the work of the Spirit. -

The Spirit-Filled Christian Life

LIBERTY BAPTIST THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY THE SPIRIT-FILLED CHRISTIAN LIFE A Thesis Project Submitted to Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree OOCTOR OF MINISlRY By Curtis Wayne Brown North Uxbridge, Massachusetts May, 2003 LIBERTY BAPTIST THEOLCX;]CAL SEMINARY THESIS PROjECf APP~~OVAL SHEET GRADE :MENTOR READER i ABSTRACT TIlE SPIRIT-FILLED LIFE Curtis W. Brown Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary ~entor:l)r. Ine~er The Scriptures teach that Christians are to be "filled or controlled" by God, the Holy Spirit. This thesis will define what the Bible teaches regarding how the Holy Spirit co~es to dwell within a person, what is involved in continually sub~tting the heart to the Holy Spirit's filling or control, and what are the behavioral and attitude ~anifestations in a Christian when controlled by the Holy Spirit. The filling of the Holy Spirit will be discussed in the life of the individual Christian, his family and the local church as seen in Ephesians 5:18- 6:17, Galatians 5:22-23, Ro~ans, I Corinthians and Acts. Abstract length: 106 words ',. 11 CONTENTS Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION.............................................. 1 Statement of the Problem........................................ 3 Definition of Terms............................................. 3 Statement of Limitations........................................ .4 Review of the Literature......................................... 4 The Biblical and Theological Bases of the Thesis•................... 45 The Design and Methodology -

Thinking in the Spirit: the Emergence of Latin American

THINKING IN THE SPIRIT: THE EMERGENCE OF LATIN AMERICAN PENTECOSTAL SCHOLARS AND THEIR PNEUMATOLOGY OF SOCIAL CONCERN A thesis presented to the faculty of the Center for International Studies of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Sean S. O’Neil August 2003 This thesis entitled THINKING IN THE SPIRIT: THE EMERGENCE OF LATIN AMERICAN PENTECOSTAL SCHOLARS AND THEIR PNEUMATOLOGY OF SOCIAL CONCERN By Sean S. O’Neil has been approved for the Department of Latin American Studies and the Center for International Studies Thomas W. Walker Professor of Political Science Josep Rota Director, Center for International Studies O’NEIL, SEAN S. M.A. August 2003. Latin American Studies Thinking in the Spirit: The Emergence of Latin American Pentecostal Scholars and Their Theology of Social Concern (153 pp.) Director of Thesis: Thomas Walker Latin American Pentecostalism is often characterized as being either socially and politically conservative or apolitical. Nevertheless, Latin American Pentecostal scholars have expressed progressive political and social concerns. In this thesis, I synthesize Latin American progressive Pentecostal theology and explore the prominence given to the Holy Spirit in such doctrine. I also examine the influences of liberation theology on the movement. I argue that the emergence of progressive Latin American Pentecostal scholars has thus far been an ambiguous phenomenon. These scholars have played an important role in bringing Latin American Pentecostals into the ecumenical sphere. Also, their social doctrine seems to be both spurring and reinforcing social and political concern in some segments of grassroots Latin American Pentecostalism. On the other hand, progressive Pentecostalism has not resonated at the grassroots level to the degree that one might expect, given the marginalized social class base of Latin American Pentecostalism. -

Overcoming Holy Spirit Shyness in the Life of the Church

Overcoming Holy Spirit shyness in the life of the church Cheryl Bridges Johns T he contemporary church suffers from what James Forbes calls “Holy Spirit shyness.”1 Most Christians know that the Holy Spirit exists, but in their day-to-day existence and in the life and wor- ship of the churches they display hesitation about and even fear of the third person of the Trinity. In his popular book The Forgotten God, Francis Chan com- ments: “From my perspective, the Holy Spirit is tragically ne- glected and, for all practical purposes, forgotten. While no evangelical would deny His existence, I’m willing to bet there are millions of churchgoers across America who Most Christians cannot confidently say they have experienced know that the Holy His presence or action in their lives over the Spirit exists, but in past year. And many of them do not believe their day-to-day they can.”2 existence and in the The absence of the Holy Spirit in the lives life and worship of of Christians has made our churches places the churches they where the liturgy is void of what may be display hesitation called “real presence.” Christians profess that about and even fear Jesus is in the midst of two or three who are of the third person of gathered together in his name, but in practice the Trinity. that presence seems more like the absence. Contemporary Christians have grown accustomed to living with the absence and fearing the presence. We suffer from a bad case of what may be called Holy Spirit Deficit Disorder. -

Living Bulwark

Living Bulwark | Subscribe | Archives | PDF Back Issues | Author Index | Topic Index | Contact Us |. June / July 2018 - Vol. 98. Worship in Spirit and Truth "The hour is coming, and now is, when the true worshipers will worship the Father in Spirit and Truth, for such the Father seeks to worship him." – John 4:23 • Intro to This Issue: "In Spirit and Truth" • Worship in Spirit and Truth, by Steve Clark • What Makes for Good Worship? by Mark Kinzer • Worshiping Together in the Spirit, by Jim Cavnar • Worshiping God with Reverence and Awe, by Carlos Mantica • Truth Versus Cultural Labels, by Charles Simpson • Rediscovering the Truth and Living by It, by Servais Pincaers • A Hole-y and Leaky Christian, and Be Men and Women of Grace, by Tom Caballes • What a Fool I Was, and I Was Ashamed of Myself, by Sam Williamson • Rising From the Ashes We Proclaim "God Is Our Only Hope", Emmanuel, Aleppo, Syria • For the World: A Kairos Conference, by Jack Noun • Legacy Europe Conference: This Is My Tribe, Laura Whinnery, Ellen Mahony, Kevin Coyle • The Summer in Mission's Imprint, by Irene Campos • Whatever Is Lovely, by Clara Schwartz • Eternity's Bright Vision, Poem and Reflection on the Transfiguration of Christ, by Jeanne Kun • We Worship Him – Behold Such Beauty, Song and Lyrics by Ed Conlin • Pray by Day: Meeting the Challenge of Personal Prayer: A New Prayer App Living Bulwark is committed to fostering renewal of the whole Christian people: Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox. We especially want to give witness to the charismatic, ecumenical, evangelistic, and community dimensions of that renewal. -

![Click Link to Read]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1794/click-link-to-read-7781794.webp)

Click Link to Read]

Living Bulwark February / March 2017 - Vol. 90 Streams of Renewal – Like a Mighty River “If any one thirst, let him come to me and drink... out of his heart shall flow rivers of living water.’” – John 7:37-38 . • Intro to This Issue: Renewed by Streams of Living Waters • First Ecumenical Charismatic Renewal Conference - Kansas City 1977 • Unity in the Spirit, by Cardinal Suenens, & “The Body of My Son Is Broken" • Charismatic Bridges, by Vincent Synan, and David du Plessis the bridge builder • Growth of Pentecostal and Charismatic Renewal Streams, by Dr. Vinson Synan • 50th Anniversary of Catholic Charismatic Renewal: Beginnings, by Fr. Pat Egan • Early Cursillo Pioneers & Charismatic Renewal, Steve Clark, Ralph Martin, et al. • The Duquesne Weekend, by Patti Gallagher Mansfield and Dave Mangan • Ecumenism and Charismatic Renewal, by Steve Clark • 500th Anniversary of the Reformation and its Streams of Renewal • Roots that Refresh: The Vitality of Reformation Spirituality, by Alister McGrath • Reading Scripture with the Early Reformers • Your Word is Truth: Statement of Evangelicals and Catholics Together • Burning Your Boats, by Tom Caballes • Kairos Youth Conference in Central America & The River Flows, Ed Conlin song • Gazing on Beauty by Sam Williamson, New Springs Rise, poem by Ana Perrem • Spiritual Food for Lent: Hunger for More of God’s Nourishing Word Living Bulwark is committed to fostering renewal of the whole Christian people: Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox. We especially want to give witness to the charismatic, ecumenical, evangelistic, and community dimensions of that renewal. Living Bulwark seeks to equip Christians to grow in holiness, to apply Christian teaching to their lives, and to respond with faith and generosity to the working of the Holy Spirit in our day.