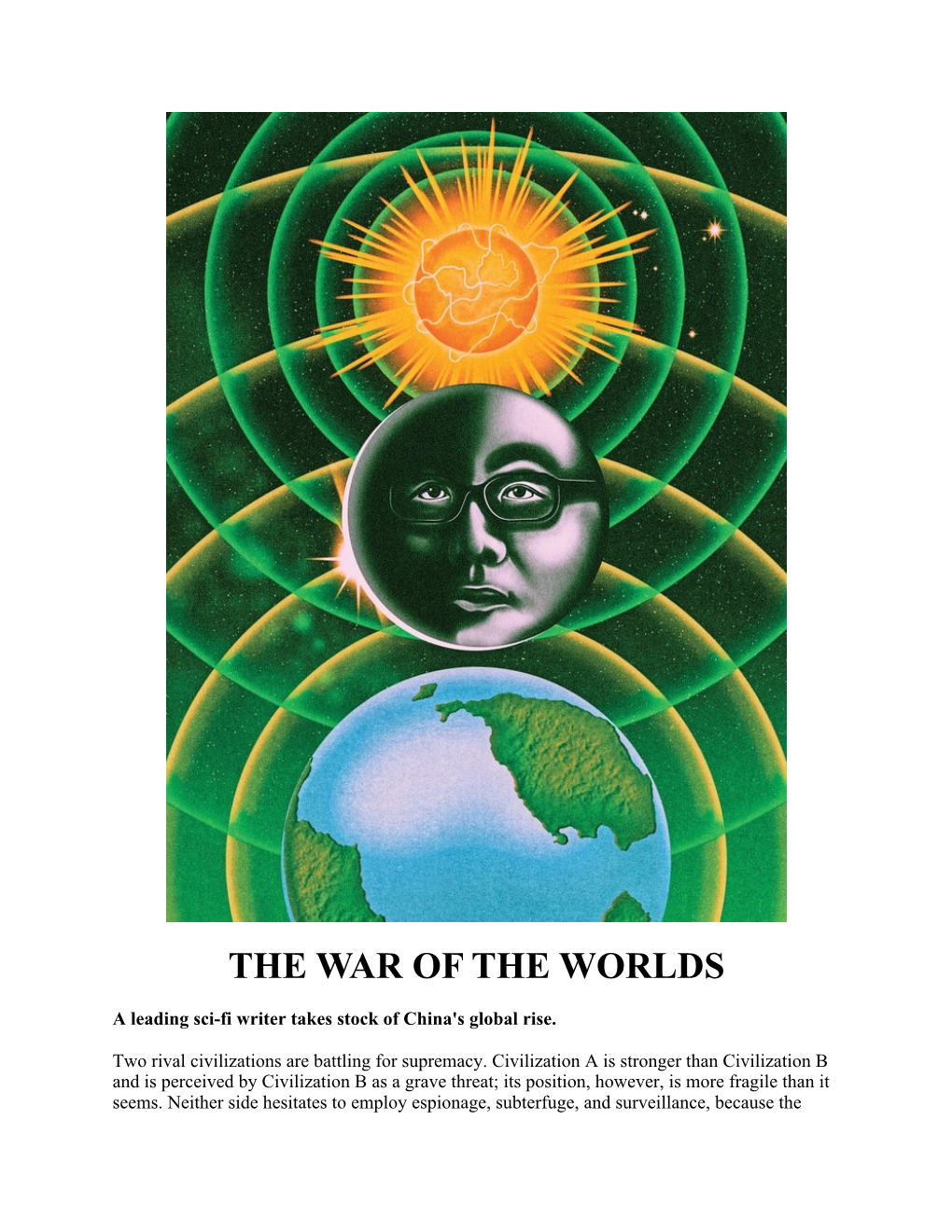

Liu Cixin the War of the Worlds.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dinosaurs and B.-E

THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE FICTION: “Dinosaurs and B.-E. M.” Page One The Age of Enlightenment brought decisive steps toward modern science, giving birth to the Scientific Revolution. During the 19th Century, the practice of science became professionalized and institutionalized, which continues to today. So, upon this stage in the 19th Century strode the “Mother of Science Fiction,” Mary Shelley (1797- 1851), whose Frankenstein of 1818 electrified the world! The promotion of the 1931 film featured a supply of smelling salts in theatre lobbies for those who might swoon! The “Co-Father of Science Fiction” was H. G. Welles (1866-1946), whose War of the Worlds of 1898, as adapted on radio by Orson Wells on Halloween, 1938, sparked a mini-panic of alien invasion terror! His The Time Machine of 1895 and The Invisible Man of 1897 became best sellers. Hints of our future were depicted by aircraft, tanks, space and time travel, nuclear weapons, satellite television, and the World-Wide Web. Page Two The other “Co-Father of Science Fiction” was the commercially-successful French author Jules Verne (1828-1905). I remember watching, with wonder, the 1954 Disney film of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea, of 1870. And I remember riding on the ride in Disneyland in California in the 1950’s. The 1959 film of Journey To The Center Of The Earth, starring James Mason and an unknown Pat Boone, featured an epic battle of dinosaurs, joining Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World, of 1912, and the 1993 film Jurassic Park with dinosaur themes in science fiction. -

The Development History of Chinese Science Fiction from Liu Cixin's Science Fiction

International Journal of Languages, Literature and Linguistics, Vol. 6, No. 3, September 2020 The Development History of Chinese Science Fiction from Liu Cixin's Science Fiction Xia Tianyi nature? At present, China's science fiction is facing many Abstract—In the history of Western literature, science fiction, problems, such as the writer's fault, the decreasing number of as an essential branch of it, has been widely loved by the masses, publications, uneven works, the stagnation of theoretical and and a crowd of outstanding science fiction novelists has been critical research work, etc. How can we stimulate the produced. With a large number of science fiction books adapted enthusiasm of the people for science fiction so that Chinese into films, the novels are also familiar to more audiences. Science fiction has been sprouting since 1902 in China, with the science fiction can develop continuously and healthily? It is a efforts of the pioneers and the relay of the latecomers, there question worthy of further discussion. have been many excellent works. But compared with the situation of western science fiction, it is not supportive of the healthy growth of science fiction in our country, and the public II. A BASIC EXPLANATION OF SCIENCE FICTION has not accepted science fiction novels. This paper will focus on the development history and current situation of science fiction Science fiction is a literal translation of western terms. It in China, and explore the differences between the creative originally meant science, which is a type of popular literature environment of Chinese and western science fiction and the with scientific imagination and innovation. -

An Ecological Alarm Bell: Liu Cixin's Science Fiction the Wandering Earth

ISSN 1923-1555[Print] Studies in Literature and Language ISSN 1923-1563[Online] Vol. 19, No. 3, 2019, pp. 60-63 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/11366 www.cscanada.org An Ecological Alarm Bell: Liu Cixin’s Science Fiction The Wandering Earth LI Jiya[a],* [a] Instructor, PhD candidate, School of Foreign Languages, Southwest fiction literature. His short and medium-length novel Jiaotong University, Chengdu, China. The Wandering Earth was published in 2008, and has * Corresponding author. been reprinted by different publishing houses many Received 6 September 2019; accepted 21 November 2019 times. The box office of the adapted film of the same Published online 26 December 2019 name surpassed 1.6 billion in 2019, and the response at home and abroad was enthusiastic, which could be Abstract regarded as a milestone of Chinese science fiction film. The Wandering Earth is another masterpiece of Liu Cixin This work surpasses ordinary sci-fi literary works in after The Three, and later adapted into a film. After its both grand imagination and meticulous details of science release, the film has won high reputation at home and and technology, and can be regarded as a literary classic. abroad. It can be regarded as a milestone of Chinese In addition to the grand narrative, we should also pay science fiction movies. From the perspective of Western attention to the realistic problems, the development of eco-criticism, the future ecological environment described natural ecology and the ideological dilemma of human in the work is fragmented; the earth disaster which has beings. The story is full of humanistic care. -

Renowned Sci-Fi Writer with a Spy Personality 刘慈欣:“间谍性格”的科幻作家

法兰克福专刊 Editor:Qu Jingfan Email:[email protected] WRITER Typesetter:Yao Zhiying F10 e interviewed two of the best and most prominent writers in China, who have a great number of passionate readers in China and around the Wworld. We hope to depict the process of their growth on the road of writing and what they are thinking about literature now. Liu Cixin: Renowned sci-fi writer with a spy personality 刘慈欣:“间谍性格”的科幻作家 By Lu Yun ver since Liu Cixin’s The Three Body Problem China’s growth of technological strength. This, too, won the world science fiction laureate Hugo is one of the characteristics of science fiction. EAward, it has turned out to be a phenomenal bestseller in Western book markets, with its audience Sci-fi authors write about worst shifting to include not just science fiction readers, but case scenarios for the universe people from all walks of life. By the end of 2019, its worldwide sales have exceeded 21 million copies, of As a science fiction author but professionally which nearly 2.3 million copies were sold overseas; trained as an engineer, he is acutely aware of the in Germany alone, close to 300,000 copies have been fact that science fiction could possibly vanish before sold. long; done for, by science and technology. As we’ve This does not just constitute a commercial almost been living in a world described by science success; Liu Cixin has become an important symbol fiction. “I believe I could turn into the last science for Chinese authors garnering international fame. -

Worldcon 75 Souvenir Book

souvenir book A Worldcon for All of Us Ireland has a rich tradition of storytelling. A BID TO BRING THE It is a land famous for its ancient myths WORLD SCIENCE FICTION and legends, great playwrights, award- winning novelists, innovative comics artists, CONVENTION TO DUBLIN and groundbreaking illustrators. Our well- FOR THE FIRST TIME established science fiction and fantasy community and all of the Dublin 2019 team AUGUST 15TH — AUGUST 19TH 2019 would consider it an honour to celebrate Ireland’s rich cultural heritage, contemporary www.dublin2019.com creators and fandoms everywhere. [email protected] We love our venue, the Convention Centre twitter.com/Dublin2019 Dublin, and we believe that its spell-binding facebook.com/dublin2019 allure will take your breath away as you watch the sun set over the city before the Kraken rises from the River Liffey! © Iain Clark 2015 A Worldcon for All of Us Ireland has a rich tradition of storytelling. A BID TO BRING THE It is a land famous for its ancient myths WORLD SCIENCE FICTION and legends, great playwrights, award- winning novelists, innovative comics artists, CONVENTION TO DUBLIN and groundbreaking illustrators. Our well- FOR THE FIRST TIME established science fiction and fantasy community and all of the Dublin 2019 team AUGUST 15TH — AUGUST 19TH 2019 would consider it an honour to celebrate Ireland’s rich cultural heritage, contemporary www.dublin2019.com creators and fandoms everywhere. THE 75TH WORLD SCIENCE FICTION CONVENTION [email protected] We love our venue, the Convention Centre twitter.com/Dublin2019 -

January 1999 to December 2008

ROBERT J. SAWYER Science Fiction Writer ᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭ PROFESSIONAL ACHIEVEMENTS A Decade in Review January 1999 to December 2008 ᔢ Novels Published * Flashforward (1999) * Calculating God (2000) * Hominids (2002, also serialized in Analog) * Humans (2003) * Hybrids (2003) * Mindscan (2005) * Rollback (2007, also serialized in Analog) ᔢ Novels Sold * Five to Tor: • Hominids (contracted 1999) • Humans (contracted 1999) • Hybrids (contracted 1999) • Mindscan (contracted 2002) • Rollback (contracted 2002) * Three to Ace: • Wake (contracted 2007, serial rights sold to Analog) • Watch (contracted 2007) • Wonder (contracted 2007) ᔢ Short Fiction * Appeared in Year’s Best SF 5 * Commissioned story for The Globe and Mail * Commissioned story for The Toronto Star * Commissioned story for Nature: International Weekly Journal of Science * Two stories in Analog (one short story, one novelette) * Commissioned stories for anthologies: • Be VERY Afraid! • Down These Dark Spaceways • Far Frontiers • Future Wars • FutureShocks • Guardsmen of Tomorrow • I, Alien • In the Shadow of the Wall • Janis Ian’s Stars • Men Writing Science Fiction as Women • Microcosms • Slipstreams • Space Inc. • Space Stations ᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭ SAWYER • Page 2 ᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭᔭ • Star Colonies • TransVersions • Visions of Liberty ᔢ Short Story Collections * Iterations and Other Stories * Identity Theft and Other Stories * Relativity: -

Liu Cixin's Wandering Path to Apocalyptic Transcendence

Liu Cixin‘s Wandering Path to Apocalyptic Transcendence: Chinese SF and the Three Poles of Modern Chinese Cultural Production An honors thesis for the Department of German, Russian, and Asian Languages & Literatures Philip A. Ballentine Tufts University, 2014 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 1 WHAT IS SCIENCE FICTION (SF)? .............................................................................................................. 4 SF AND CHINA‘S REVOLUTIONARY MODERNIZATION MOVEMENTS ..................................................... 11 THE THREE POLES OF MODERN CHINESE CULTURAL PRODUCTION ...................................................... 15 THE DIDACTIC POLE .............................................................................................................................. 18 DIDACTIC CHINESE SF IN THE LATE QING AND MAY FOURTH ERAS ..................................................... 20 DIDACTIC SF IN THE SOCIALIST PERIOD ................................................................................................. 24 DIDACTIC ―REFORM LITERATURE‖ ......................................................................................................... 27 CHINESE SF‘S MOVE TOWARDS THE ANTI-DIDACTIC POLE ....................................................... 30 ―DEATH RAY ON A CORAL ISLAND:‖ A STUDY IN DIDACTIC ‗REFORM‘ SF .......................................... 33 CHINESE SF‘S -

On the Co-Creation of Science and Science Fiction in the Social Imaginary Brad Tabas

Making Science, Making Scientists, Making Science Fiction: On the Co-Creation of Science and Science Fiction in the Social Imaginary Brad Tabas To cite this version: Brad Tabas. Making Science, Making Scientists, Making Science Fiction: On the Co-Creation of Science and Science Fiction in the Social Imaginary. Socio - La nouvelle revue des sciences sociales, Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme, 2019, pp. 71-101. 10.4000/socio.7735. hal-03000978 HAL Id: hal-03000978 https://hal-ensta-bretagne.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03000978 Submitted on 3 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License Socio La nouvelle revue des sciences sociales 13 | 2019 Science et science-fiction Making Science, Making Scientists, Making Science Fiction: On the Co-Creation of Science and Science Fiction in the Social Imaginary Faire de la science, faire des scientifiques, faire de la science-fiction : sur la cocréation de la science et de la science-fiction -

Hugo Awards Presentation Chicenv

Hugo Awards Presentation ChicenV The 49th World Science Fiction Convention 29 August through 2 September 1991 Chicon V, Inc "World Science Fiction Society", "WSFS", "World Science Fiction Convention", "NASFiC", "Science Fiction Achievement Award, and "Hugo Award" are Service Marks of the World Science Fiction Society, an unincorporated literary society. Hugo Program Book produced and edited by Jane G. Haldeman and Tina L. Jens Cover Art by Donna E. Slager Special Thanks to XPRESS GRAPHICS LINOTYPE IMAGESETTING 137 North Oak Park Ave Suite 200 Oak Park, IL 60301 708-848-8651 The Hugo Award The Hugo is Science Fiction’s Achievement Award. The name “Hugo" is for Hugo Gernsback. Nominees are chosen for publication or activities in the previous calendar year. Hugos have been awarded annually at the World Science Fiction Convention since 1953. The only exception was 1954 when the idea was dropped for a year. The award is in the shape of a rocket ship based on an Oldsmobile hood ornament. The original designs were created by Ben Jason (in 1955) and Jack McKnight. If you would like to know more there is an article in the Chicon V Program book. This Year’s Presenters Master of Ceremonies Marta Randall Hugo Balloting Committee Darrell Martin Ross Pavlac Chicon V Special Award Kathleen Meyer First Fandom’s Award Frederik Pohl Japan’s Seiun-Sho Takumi Shibano John W Campbell Award Stanley Schmidt The Hugo Ceremony Staff Department Head Jane G. Haldeman Assistant Department Head Tina L. Jens Secret Advisor Douglas H. Price D.l. House Manager George Krause Hugo Envoy Crew Martin Costello Nancy Mildebrand Martha Fabish John Mitchell Winifred Halsey Eve Schwingel William Henry Hay, M.D. -

Science Fiction Booklist

MOUNT VERNON CITY LIBRARY BOOKLISTS Science Fiction Adams, Douglas The Hitchhiker’s Guide trilogy The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy Sci-Fi often takes us to a possible future or even an Asimov, Isaac alternate history and frequently has a technological I, Robot theme. Unlike Fantasy Fiction, Sci-Fi is driven by science rather than magic. Find these books or series in Fiction Bacigalupi, Paolo The Windup Girl under the author's last name or browse for the Sci-Fi sticker on the book spine. Bear, Greg Darwin’s Children Moving Mars Bradbury, Ray The Martian Chronicles Jemisin, N.K. Robinson, Kim Stanley Bradley, Marion Zimmer Broken Earth series Shaman Rediscovery The Fifth Season Aurora New York 2140 Bujold, Lois McMaster The Vorkosigan Saga Kenyon, S herrilyn Cryoburn Cloak & Silence Russell, Mary Doria The Sparrow Card, Orson Scott Le Guin, Ursula K. Ender Saga The Left Hand of Darkness Scalzi, John Ender’s Game A Fisherman of the Inland Sea : Old Man’s War Universe Fleet School Science Fiction Stories Old Man’s War Children of the Fleet Leckie, Ann Stephenson, Neal Imperial Radch series Anathem Clarke, A rthur C. 2001: A Space Odyssey The Raven Tower Seveneves Liu, Cixin Wells, H.G. Corey, James Three Body series Expanse Series The War of the Worlds The Three-Body Problem The Invisible Man Leviathan Wakes Martin, George R.R. VanderMeer, Jeff Dick, Philip K. Hunter’s Run The Man in the High Castle Southern Reach trilogy Dangerous Women Annihilation A Scanner Darkly McCaffrey, Anne Vinge, Vernor Gibson, William Freedom Series Zones of Thought series Neuromancer Freedom’s Landing A Deepness in the Sky Heinlein , Robert McCammon, Robert Walton, Jo Stranger in a Strange Land The Border Among Others Starship Troopers Variable Star Miller, Walter Willis, Connie A Canticle for Leibowitz Crosstalk Herbert, Frank Beyond Armageddon All Clear Dune Niven, Larry Yu, Charles Huxley, Aldous The Draco Tavern How to Live Safely in a Science Brave New World Saturn's Race Fictional Universe Parrish, Robin Offworld. -

China's Links with Europe Strengthened

Demand grows Business downturn Transformative art for individual Australia sees worst economic Remote village workshop provides cultural food servings slump on record in 2nd quarter CHINA, PAGE 6 opportunities to left-behind kids BUSINESS, PAGE 15 WORLD, PAGE 12 CHINADAILY THURSDAY, September 3, 2020 www.chinadailyhk.com HK $10 China’s links Learning about courage with Europe strengthened Wang says 5 nations he visited agreed to reinforce unity, oppose ‘decoupling’ By WANG QINGYUN in Beijing by the pandemic, rising unilateral- and CHEN WEIHUA in Brussels ism, attempts to “decouple” and heightened international rivalry, China and five European coun- he said. tries have agreed to strengthen Wang called for China and joint efforts to bolster unity and Europe to carefully plan high-level oppose “decoupling” to prevent the exchanges and urged they finish world from slipping back into the negotiations over a bilateral invest- grip of “the law of the jungle”. ment treaty this year and sign a The countries voiced a strong strategic plan for bilateral coopera- appeal to safeguard multilateral- tion for the next five years as soon ism, State Councilor and Foreign as possible. Minister Wang Yi said on Tuesday Both sides should also work at a joint news conference with together firmly to promote interna- German Foreign Minister Heiko tional cooperation to tackle climate Maas in Berlin. change and enhance digital cooper- A retired teacher tells students about the role of China’s New Fourth Army in the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931- Calling for China and Europe to ation, Wang said. 45) at a memorial hall in Deqing county, Zhejiang province, on Wednesday. -

Adult Author's New Gig Adult Authors Writing Children/Young Adult

Adult Author's New Gig Adult Authors Writing Children/Young Adult PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 31 Jan 2011 16:39:03 UTC Contents Articles Alice Hoffman 1 Andre Norton 3 Andrea Seigel 7 Ann Brashares 8 Brandon Sanderson 10 Carl Hiaasen 13 Charles de Lint 16 Clive Barker 21 Cory Doctorow 29 Danielle Steel 35 Debbie Macomber 44 Francine Prose 53 Gabrielle Zevin 56 Gena Showalter 58 Heinlein juveniles 61 Isabel Allende 63 Jacquelyn Mitchard 70 James Frey 73 James Haskins 78 Jewell Parker Rhodes 80 John Grisham 82 Joyce Carol Oates 88 Julia Alvarez 97 Juliet Marillier 103 Kathy Reichs 106 Kim Harrison 110 Meg Cabot 114 Michael Chabon 122 Mike Lupica 132 Milton Meltzer 134 Nat Hentoff 136 Neil Gaiman 140 Neil Gaiman bibliography 153 Nick Hornby 159 Nina Kiriki Hoffman 164 Orson Scott Card 167 P. C. Cast 174 Paolo Bacigalupi 177 Peter Cameron (writer) 180 Rachel Vincent 182 Rebecca Moesta 185 Richelle Mead 187 Rick Riordan 191 Ridley Pearson 194 Roald Dahl 197 Robert A. Heinlein 210 Robert B. Parker 225 Sherman Alexie 232 Sherrilyn Kenyon 236 Stephen Hawking 243 Terry Pratchett 256 Tim Green 273 Timothy Zahn 275 References Article Sources and Contributors 280 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 288 Article Licenses License 290 Alice Hoffman 1 Alice Hoffman Alice Hoffman Born March 16, 1952New York City, New York, United States Occupation Novelist, young-adult writer, children's writer Nationality American Period 1977–present Genres Magic realism, fantasy, historical fiction [1] Alice Hoffman (born March 16, 1952) is an American novelist and young-adult and children's writer, best known for her 1996 novel Practical Magic, which was adapted for a 1998 film of the same name.