The Empire Strikes Back Syllabus Fall-17 Sep-6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia

10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia Hugo Award Hugo Award, any of several annual awards presented by the World Science Fiction Society (WSFS). The awards are granted for notable achievement in science �ction or science fantasy. Established in 1953, the Hugo Awards were named in honour of Hugo Gernsback, founder of Amazing Stories, the �rst magazine exclusively for science �ction. Hugo Award. This particular award was given at MidAmeriCon II, in Kansas City, Missouri, on August … Michi Trota Pin, in the form of the rocket on the Hugo Award, that is given to the finalists. Michi Trota Hugo Awards https://www.britannica.com/print/article/1055018 1/10 10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia year category* title author 1946 novel The Mule Isaac Asimov (awarded in 1996) novella "Animal Farm" George Orwell novelette "First Contact" Murray Leinster short story "Uncommon Sense" Hal Clement 1951 novel Farmer in the Sky Robert A. Heinlein (awarded in 2001) novella "The Man Who Sold the Moon" Robert A. Heinlein novelette "The Little Black Bag" C.M. Kornbluth short story "To Serve Man" Damon Knight 1953 novel The Demolished Man Alfred Bester 1954 novel Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury (awarded in 2004) novella "A Case of Conscience" James Blish novelette "Earthman, Come Home" James Blish short story "The Nine Billion Names of God" Arthur C. Clarke 1955 novel They’d Rather Be Right Mark Clifton and Frank Riley novelette "The Darfsteller" Walter M. Miller, Jr. short story "Allamagoosa" Eric Frank Russell 1956 novel Double Star Robert A. Heinlein novelette "Exploration Team" Murray Leinster short story "The Star" Arthur C. -

Read 2021 Book Lists

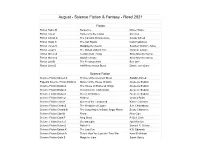

August - Science Fiction & Fantasy - Read 2021 Fiction Fiction Baker.M Borderline Mishell Baker Fiction Cho.Z Sorcerer to the Crown Zen Cho Fiction Ghosh.A The Calcutta Chromosome Amitav Ghosh Fiction Hopki.N The Salt Roads Nalo Hopkinson Fiction Jones.S Mapping the Interior Stephen Graham Jones Fiction Laval.V The Ballad of Black Tom Victor D. LaValle Fiction Moren.S Certain Dark Things Silvia Moreno-Garcia Fiction Moren.S Signal to Noise Silvia Moreno-Garcia Fiction Okri.B The Freedom Artist Ben Okri Fiction Older.D Half-Resurrection Blues Daniel Jose Older Science Fiction Science Fiction Ahmed.S Throne of the Crescent Moon Saladin Ahmed Paperbk Science Fiction Bodar.A Master of the House of Darts Aliette de Bodard Science Fiction Bodar.A The House of Shattered Wings Aliette de Bodard Science Fiction Bodar.A Servant of the Underworld Aliette de Bodard Science Fiction Bodar.A Seven of Infinities Aliette de Bodard Science Fiction Butle.O Kindred Octavia Butler Science Fiction Calle.K Queen of the Conquered Kacen Callender Science Fiction Chakr.S The Kingdom of Copper S.A. Chakraborty Science Fiction Chamb.B The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet Becky Chambers Science Fiction Cipri.N Finna Nino Cipri Science Fiction Clark.P Ring Shout P. Djeli Clark Science Fiction Danie.A Dreadnought April Daniels Science Fiction Delan.S Babel-17 Samuel R. Delany Science Fiction Edwar.K The Last Sun K.D. Edwards Science Fiction Elmoh.A This is How You Lose the Time War Amal El-Mohtar Science Fiction Gaile.S Magic for Liars Sarah Gailey Science Fiction Gaile.S River of Teeth Sarah Gailey Science Fiction Gratt.T The Queens of Innis Lear Tessa Gratton Science Fiction Hende.A The Year of the Witching Alexis Henderson Science Fiction Hopki.N Midnight Robber Nalo Hopkinson Science Fiction Hossa.S The Gurkha and the Lord of Tuesday Saad Hossain Science Fiction Huang.S Burning Roses S.L. -

Dinosaurs and B.-E

THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE FICTION: “Dinosaurs and B.-E. M.” Page One The Age of Enlightenment brought decisive steps toward modern science, giving birth to the Scientific Revolution. During the 19th Century, the practice of science became professionalized and institutionalized, which continues to today. So, upon this stage in the 19th Century strode the “Mother of Science Fiction,” Mary Shelley (1797- 1851), whose Frankenstein of 1818 electrified the world! The promotion of the 1931 film featured a supply of smelling salts in theatre lobbies for those who might swoon! The “Co-Father of Science Fiction” was H. G. Welles (1866-1946), whose War of the Worlds of 1898, as adapted on radio by Orson Wells on Halloween, 1938, sparked a mini-panic of alien invasion terror! His The Time Machine of 1895 and The Invisible Man of 1897 became best sellers. Hints of our future were depicted by aircraft, tanks, space and time travel, nuclear weapons, satellite television, and the World-Wide Web. Page Two The other “Co-Father of Science Fiction” was the commercially-successful French author Jules Verne (1828-1905). I remember watching, with wonder, the 1954 Disney film of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea, of 1870. And I remember riding on the ride in Disneyland in California in the 1950’s. The 1959 film of Journey To The Center Of The Earth, starring James Mason and an unknown Pat Boone, featured an epic battle of dinosaurs, joining Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World, of 1912, and the 1993 film Jurassic Park with dinosaur themes in science fiction. -

The Development History of Chinese Science Fiction from Liu Cixin's Science Fiction

International Journal of Languages, Literature and Linguistics, Vol. 6, No. 3, September 2020 The Development History of Chinese Science Fiction from Liu Cixin's Science Fiction Xia Tianyi nature? At present, China's science fiction is facing many Abstract—In the history of Western literature, science fiction, problems, such as the writer's fault, the decreasing number of as an essential branch of it, has been widely loved by the masses, publications, uneven works, the stagnation of theoretical and and a crowd of outstanding science fiction novelists has been critical research work, etc. How can we stimulate the produced. With a large number of science fiction books adapted enthusiasm of the people for science fiction so that Chinese into films, the novels are also familiar to more audiences. Science fiction has been sprouting since 1902 in China, with the science fiction can develop continuously and healthily? It is a efforts of the pioneers and the relay of the latecomers, there question worthy of further discussion. have been many excellent works. But compared with the situation of western science fiction, it is not supportive of the healthy growth of science fiction in our country, and the public II. A BASIC EXPLANATION OF SCIENCE FICTION has not accepted science fiction novels. This paper will focus on the development history and current situation of science fiction Science fiction is a literal translation of western terms. It in China, and explore the differences between the creative originally meant science, which is a type of popular literature environment of Chinese and western science fiction and the with scientific imagination and innovation. -

An Ecological Alarm Bell: Liu Cixin's Science Fiction the Wandering Earth

ISSN 1923-1555[Print] Studies in Literature and Language ISSN 1923-1563[Online] Vol. 19, No. 3, 2019, pp. 60-63 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/11366 www.cscanada.org An Ecological Alarm Bell: Liu Cixin’s Science Fiction The Wandering Earth LI Jiya[a],* [a] Instructor, PhD candidate, School of Foreign Languages, Southwest fiction literature. His short and medium-length novel Jiaotong University, Chengdu, China. The Wandering Earth was published in 2008, and has * Corresponding author. been reprinted by different publishing houses many Received 6 September 2019; accepted 21 November 2019 times. The box office of the adapted film of the same Published online 26 December 2019 name surpassed 1.6 billion in 2019, and the response at home and abroad was enthusiastic, which could be Abstract regarded as a milestone of Chinese science fiction film. The Wandering Earth is another masterpiece of Liu Cixin This work surpasses ordinary sci-fi literary works in after The Three, and later adapted into a film. After its both grand imagination and meticulous details of science release, the film has won high reputation at home and and technology, and can be regarded as a literary classic. abroad. It can be regarded as a milestone of Chinese In addition to the grand narrative, we should also pay science fiction movies. From the perspective of Western attention to the realistic problems, the development of eco-criticism, the future ecological environment described natural ecology and the ideological dilemma of human in the work is fragmented; the earth disaster which has beings. The story is full of humanistic care. -

Ray Bradbury Has Inspired Generations of Readers to Dream, BUBONICON FRIEND AMONG Think and Create," the Statement Said

ASFACTS 2012 JULY “S UMMER RAINS , S TUPID DRAINS ” I SSUE ROGERS & D ENNING HOSTING PRE -CON PARTY Patricia Rogers and Scott Denning will uphold a local fannish tradition when they host the Bubonicon 44 Pre-Con Party 7:30-10:30 pm Thursday, August 23, at their home in Bernalillo – located at 909 Highway 313. The easiest way to reach the house is north on I-25 to exit 242 east (Rio Rancho’s backdoor and the road to Cuba). At Highway 313, turn right to head north. Look Martian Chronicles and Something Wicked This Way for the Country Store, the John Deere sign and Mile Comes , died June 5 after a lengthy illness. He was 91 Marker 9. Their house is on the west side of the road, with years old. plenty of parking on the shoulder. Bradbury "died peacefully [in the] night, in Los An- In addition to socializing, attendees can help assem- geles, after a lengthy illness," his publisher, Harper- ble the membership packets, and check out the 2012 con t Collins, said in a written statement. -shirt with artwork by Ursula Vernon. Bradbury's books and 600 short stories predicted a Please bring snacks and drinks to share, plus plates, variety of things, including the emergence of ATMs and napkins, cups and some ice. As with any hosted party, live broadcasts of fugitive car chases. please help keep the house clean and in good shape! "In a career spanning more than 70 years, Ray Bradbury has inspired generations of readers to dream, BUBONICON FRIEND AMONG think and create," the statement said. -

Renowned Sci-Fi Writer with a Spy Personality 刘慈欣:“间谍性格”的科幻作家

法兰克福专刊 Editor:Qu Jingfan Email:[email protected] WRITER Typesetter:Yao Zhiying F10 e interviewed two of the best and most prominent writers in China, who have a great number of passionate readers in China and around the Wworld. We hope to depict the process of their growth on the road of writing and what they are thinking about literature now. Liu Cixin: Renowned sci-fi writer with a spy personality 刘慈欣:“间谍性格”的科幻作家 By Lu Yun ver since Liu Cixin’s The Three Body Problem China’s growth of technological strength. This, too, won the world science fiction laureate Hugo is one of the characteristics of science fiction. EAward, it has turned out to be a phenomenal bestseller in Western book markets, with its audience Sci-fi authors write about worst shifting to include not just science fiction readers, but case scenarios for the universe people from all walks of life. By the end of 2019, its worldwide sales have exceeded 21 million copies, of As a science fiction author but professionally which nearly 2.3 million copies were sold overseas; trained as an engineer, he is acutely aware of the in Germany alone, close to 300,000 copies have been fact that science fiction could possibly vanish before sold. long; done for, by science and technology. As we’ve This does not just constitute a commercial almost been living in a world described by science success; Liu Cixin has become an important symbol fiction. “I believe I could turn into the last science for Chinese authors garnering international fame. -

Urban Fantasy Secret Societies and Shady Characters Fairy Tales And

Urban Fantasy Magical Realism —Ninth House by Leigh Bardugo —The House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende —Storm Front by Jim Butcher —Summerlong by Peter S. Beagle —Highfire by Eoin Colfer —Ficciones by Jorge Luis Borges —The City We Became by N.K. Jemisin —The Book of Hidden Things by Francesco Dimitri —Darkfever by Karen Marie Moning —A Green and Ancient Light by Frederic S. Durbin —Witchmark by C.L. Polk —Like Water for Chocolate by Laura Esquivel —One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Secret Societies and Márquez Shady Characters —Exit West by Mohsin Hamid —The Shape of Water by Guillermo del Toro —The Invisible Library by Genevieve Cogman —The Binding by Bridget Collins —Lent by Jo Walton —The House in the Cerulean Sea by TJ Klune Graphic Novels —The Lies of Locke Lamora by Scott Lynch —American Gods by Neil Gaiman —The Night Circus by Erin Morgenstern —Neverwhere by Neil Gaiman —The Starless Sea by Erin Morgenstern —Monstress by Marjorie Liu —A Darker Shade of Magic by V.E. Schwab —The Complete ElfQuest by Wendy Pini Fairy Tales and —Nimona by Noelle Stevenson Mythology —Rat Queens by Kurtis J. Wiebe —The Bear and the Nightingale by Katherine Short Stories Arden —The People in the Castle by Joan Aiken —The Blue Salt Road by Joanne M. Harris —The Bloody Chamber by Angela Carter —A Pocketful of Crows by Joanne M. Harris Explore the amazing worlds of —Norse Mythology by Neil Gaiman —The Snow Child by Eowyn Ivey Fantasy! From far off lands full of —Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister by Gregory —Get in Trouble by Kelly Link magic and wonder to the Maguire —Dreams of Distant Shores by Patricia A. -

May 2020 Dear Incoming Honors Science

May 2020 Dear Incoming Honors Science Fiction and Fantasy Literature Student, With your summer vacation right around the corner, I know you are looking forward to having some time to rest, read some good books, and enjoy the lovely weather. I am excited to tell you about the books you’ll be reading for your summer reading assignment. This summer, you will read two books and complete an assignment for each book. Please notice that you must read the required book, but that you have a choice of selected options for your second book. Book #1: Required Reading The Hobbit by J.R.R Tolkien ISBN-13: 978-0547928227 Book #2: Reader’s Choice (choose one) Ender’s Game by Orson Scott Card Caves of Steel by Isaac Asimov New Spring by Robert Jordan Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury Dune by Frank Herbert The Three-Body Problem by Cixin Liu (Author), Ken Liu (Translator) Book Assignments For both books, you will complete a Dialectical Journal logging your response and analysis as you read. Your dialectical journal should include 20 entries per book. You must upload each Dialectical Journal to the corresponding www.turnitin.com assignment no later than August 5, 2020. Students are expected to submit their assignments online at: http://www.turnitin.com. Certain assignments will also require a hard copy be brought to class. If a hard copy is not brought to class, students forfeit all points for the related in-class activity. Class Name: Honors Science Fiction and Fantasy Literature-2020 Class ID: 24742543 Password: Dragons Directions: 1. -

Liu Cixin's Wandering Path to Apocalyptic Transcendence

Liu Cixin‘s Wandering Path to Apocalyptic Transcendence: Chinese SF and the Three Poles of Modern Chinese Cultural Production An honors thesis for the Department of German, Russian, and Asian Languages & Literatures Philip A. Ballentine Tufts University, 2014 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 1 WHAT IS SCIENCE FICTION (SF)? .............................................................................................................. 4 SF AND CHINA‘S REVOLUTIONARY MODERNIZATION MOVEMENTS ..................................................... 11 THE THREE POLES OF MODERN CHINESE CULTURAL PRODUCTION ...................................................... 15 THE DIDACTIC POLE .............................................................................................................................. 18 DIDACTIC CHINESE SF IN THE LATE QING AND MAY FOURTH ERAS ..................................................... 20 DIDACTIC SF IN THE SOCIALIST PERIOD ................................................................................................. 24 DIDACTIC ―REFORM LITERATURE‖ ......................................................................................................... 27 CHINESE SF‘S MOVE TOWARDS THE ANTI-DIDACTIC POLE ....................................................... 30 ―DEATH RAY ON A CORAL ISLAND:‖ A STUDY IN DIDACTIC ‗REFORM‘ SF .......................................... 33 CHINESE SF‘S -

YA Short 0820

Short Reads for People With No Time Walking Awake by N.K. Jemisin Walking Awake "“Walking Awake” finds a technician in the grip of a moral crisis as she continues to feed children to alien masters that harvest their bodies and minds, and must decide if she will step up and stop them." - Martin Cahill, Community, Revolution, and Power: How Long ‘til Black Future Month? by N. K. Jemisin Read or listen to "Walking Awake" online. After reading "Walking Awake", read this brief interview with NK Jemisin about the story. "Walking Awake" is also available in NK Jemisin's collection of short stories, How Long 'til Black Future Month? Click here to request a copy. "N(ora). K. Jemisin is a New York Times-bestselling author of speculative fiction short stories and novels, who lives and writes in Brooklyn, NY. In 2018, she became the first author to win three Best Novel Hugos in a row for her Broken Earth trilogy. She has also won a Nebula Award, two Locus Awards, and a number of other honors." - biography from the author. Learn more about N.K. Jemisin. Write it down! questions What is important about names and language in this world? Why are certain words (i.e. caregiver), and certain names (i.e. Ten-36) used? Why do you think Sadie is diagnosed with a mental illness when she starts to have vivid dreams as a child? What would it mean for this world if dreams were not an illness or a problem? Why does the initial way humans fought the Masters fail? Do you think Enri and Sadie's way of fighting is different? If so, how? Why did NK Jemisin choose to write the story in this way -- with the first battle failing? Why does Olivia seem to feel comfortable doing what she does, and offering up Ten-36? What is the significance in the story of learning that Masters were created by humans? What do you notice about who is alone and who is together in this story? How does this relate/conflict to the story Sadie tells students about humans being lonely before the Masters? NK Jemisin says, "it's certainly possible" that there are people who have avoided the Masters rule. -

On the Co-Creation of Science and Science Fiction in the Social Imaginary Brad Tabas

Making Science, Making Scientists, Making Science Fiction: On the Co-Creation of Science and Science Fiction in the Social Imaginary Brad Tabas To cite this version: Brad Tabas. Making Science, Making Scientists, Making Science Fiction: On the Co-Creation of Science and Science Fiction in the Social Imaginary. Socio - La nouvelle revue des sciences sociales, Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme, 2019, pp. 71-101. 10.4000/socio.7735. hal-03000978 HAL Id: hal-03000978 https://hal-ensta-bretagne.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03000978 Submitted on 3 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License Socio La nouvelle revue des sciences sociales 13 | 2019 Science et science-fiction Making Science, Making Scientists, Making Science Fiction: On the Co-Creation of Science and Science Fiction in the Social Imaginary Faire de la science, faire des scientifiques, faire de la science-fiction : sur la cocréation de la science et de la science-fiction