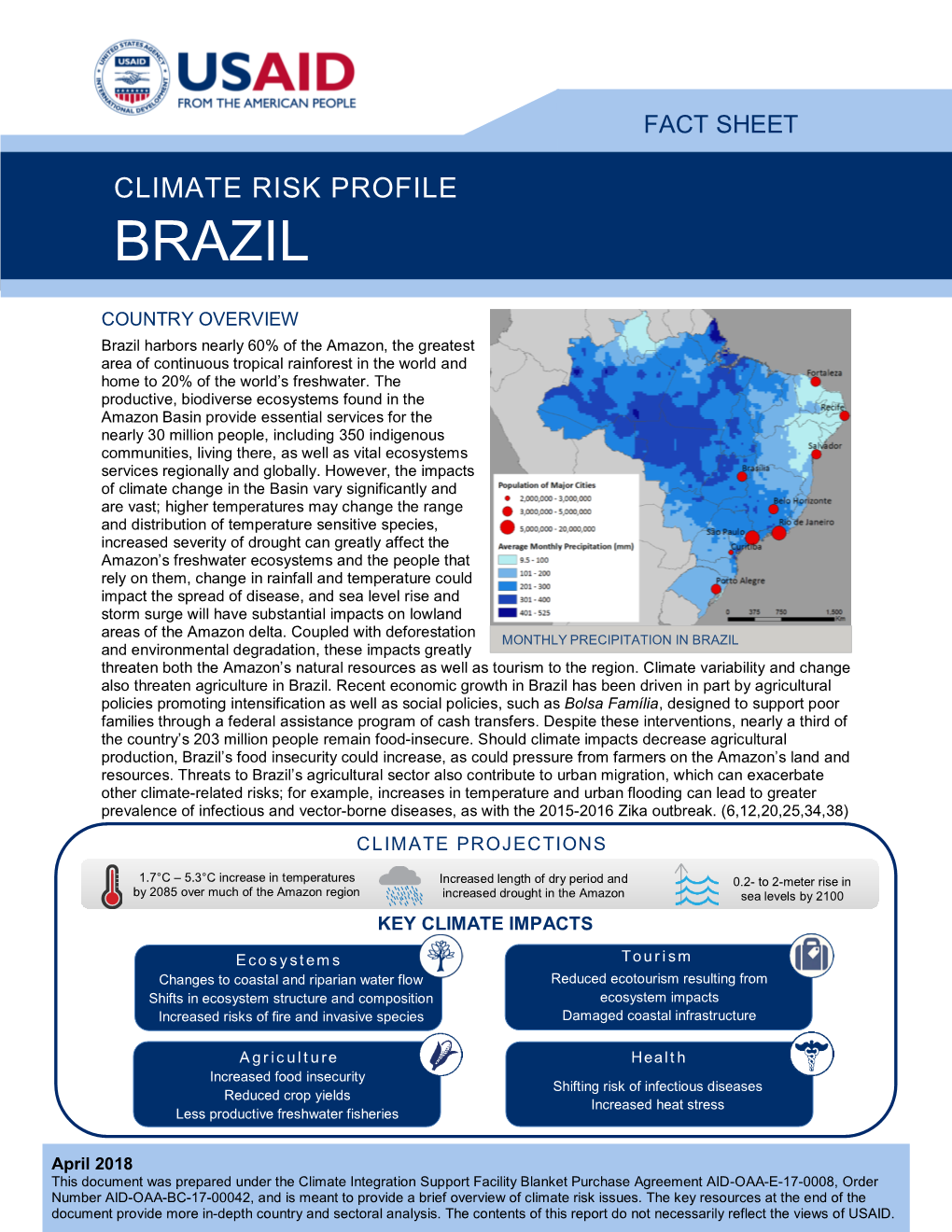

Climate Risk Profile: Brazil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Climate of Brazil Climate Data

Lesson Two: The Climate of Brazil Climate Data BRASILIA Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec Temperature °C 21 21 22 21 20 19 18 20 22 22 21 21 Rainfall mm 247 217 180 123 38 8 11 13 55 166 231 246 RIO DE JANEIRO Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec Temperature °C 26 27 26 24 23 22 21 22 22 23 24 25 Rainfall mm 137 130 135 94 68 42 41 44 53 85 97 134 SALVADOR Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec Temperature °C 26 27 27 26 25 24 24 24 24 25 26 26 Rainfall mm 138 142 151 309 359 243 175 127 102 114 137 142 MANAUS Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec Temperature °C 26 26 26 26 26 26 27 27 28 28 27 27 Rainfall mm 264 289 335 311 279 115 85 47 73 112 173 219 CURITIBA Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec Temperature °C 20 20 19 17 15 12 13 14 15 17 18 19 Rainfall mm 165 142 126 90 99 98 89 74 115 134 123 150 Lesson two: The Brazilian Climate Why did the England football coach Roy Hodgson not want the England football team to play in Manaus? BBC Sport - 2014 World Cup: Playing in Manaus 'not ideal' - Roy Hodgson Where is Manaus? Manaus Map of Brazil © Douglas Fernandes, Flickr Creating a Climate Graph Success criteria for a climate graph What should be included in a success criteria for a climate graph? Success criteria for a climate graph Title Bar chart for rainfall and line graph for temperature Label the x axis Months Label the y axis Rainfall in millimeters (mm) Temperature in Degrees Celsius Include a key Creating a climate graph Use the data from the five locations in Brazil to create climate graphs: Brasilia Rio De Janeiro Salvador Manaus Curitiba Using your climate graph What does your graph tell you about the climate in different cities in Brazil? print-graph-paper.com Weather or Climate? “I think we should move to France where it is warmer.” “My washing will never dry today.” “December is wet and cold.” “Where should we go for our skiing holiday this year?” “There is too much fog for the plane to land.” “Bananas grow in Jamaica because it is hot.” “Sports Day is cancelled. -

CERRADO BIOME an Assessment Developed for the Climate and Land Use Alliance by CEA Consulting August 2016 MAP 1: BRAZIL’S CERRADO BIOME

CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR CONSERVATION, AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION, AND SOCIAL INCLUSION IN THE CERRADO BIOME An assessment developed for the Climate and Land Use Alliance by CEA Consulting August 2016 MAP 1: BRAZIL’S CERRADO BIOME AREA OF DETAIL Brazil Sources: Reference layers: http://www.naturalearthdata.com/ Matopiba: http://www.ibge.gov.br/english/geociencias/default_prod.shtm Cerrado Biome: http://maps.lapig.iesa.ufg.br/lapig.html Photo: CEA CONTENTS About this report 2 Executive summary 3 Introduction 13 Proposed priorities 18 PRIORITY 1 Strong implementation of the Forest Code 18 PRIORITY 2 Protection and management of community and conservation lands 26 PRIORITY 3 Incentives for conservation 36 PRIORITY 4 Improved sustainability and productivity of existing agricultural lands and pasturelands 40 PRIORITY 5 Cover photos: Building the case for biodiversity ponsulak/Shutterstock (soybeans) Bento Viana/ISPN (palm and cut fruit) and landscape conservation 46 Paulo Vilela/Shutterstock (soy plants) Peter Caton/ISPN (baskets) Research agenda 49 Alf Ribeiro/Shutterstock (tractors) Conclusion 51 ABOUT THIS REPORT This document outlines a set of opportunities that can contribute to conservation of biodiversity and ecosystems, growth in agricultural production, and support for social inclusion and traditional livelihoods in Brazil’s Cerrado biome for the future of the region. It was prepared by CEA Consulting at the request of the Climate and Land Use Alliance (CLUA), a philanthropic collaborative of the ClimateWorks Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. It was supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the ClimateWorks Foundation. The intended audience for this report is the full range of stakeholders working in the Cerrado biome; the recommendations included here are not designed for any particular actor and in fact would necessarily need to be undertaken by many different actors. -

A Study of Brazilian Capitals Correlação Entre Clima, Tama

J. Health Biol Sci. 2020;8(1):1-5 doi: 10.12662/2317-3206jhbs.v8i1.3358.p1-5.2020 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Correlation between weather, population size and COVID-19 pandemic: a study of Brazilian capitals Correlação entre clima, tamanho da população e pandemia da COVID-19:um estudo das capitais brasileiras Renato Américo de Araújo Neto1 , Géssyca Cavalcante de Melo2 1. Docente do curso de Fisioterapia pelo Centro Universitário Maurício de Nassau, Maceió, Alagoas, Brasil. 2. Docente do curso de Enfermagem pela Universidade Estadual de Ciências da Saúde, Maceió, Alagoas, Brasil Abstract Objective: To analyze the correlation between weather, population size and cases of COVID-19 in the capitals of Brazil. Methods : All confirmed cases of COVID-19 infection, from the first confirmed case from February 26 until May 01, 2020 were included. For weather variables, average temperature (°C), dew point (°C), average humidity (%) and wind speedResults (m s-1) were extracted from the Instituto de Meteorologia database. The population size of each capital was used as a control variable, with data obtained from Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Spearman rank correlation tests were utilized to examine the correlation between variables. : TheConclusion analysis showed a significant and strong positive correlation between the total cases of COVID-19 and the population size (p<0,01). There was a significant positive correlation with the average humidity of the air and cumulative cases (p<0,05). There was no significant correlation with other climate variables. : Our results confront some expectations commented around the world about a possible seasonality of COVID-19 during periods of low humidity and can assist government and health authorities in decision making to control the pandemic. -

Bacteria, Virus, and Parasite Research

Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 57(1):27-32, January-February, 2015 http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0036-46652015000100004 ENTEROPATHOGENS DETECTED IN A DAYCARE CENTER, SOUTHEASTERN BRAZIL: BACTERIA, VIRUS, AND PARASITE RESEARCH Edna Donizetti Rossi CASTRO(1)*, Marcela Cristina Braga Yassaka GERMINI(1)*, Joana D’Arc Pereira MASCARENHAS(2), Yvone Benchimol GABBAY(2), Ian Carlos Gomes de LIMA(2), Patrícia dos Santos LOBO(2), Valéria Daltibari FRAGA(1), Luciana Moran CONCEIÇÃO(1), Ricardo Luiz Dantas MACHADO(1,3) & Andréa Regina Baptista ROSSIT(1,4) SUMMARY Introduction: The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence and etiological profile of enteropathogens in children from a daycare center. Methods: From October 2010 to February 2011 stool samples from 100 children enrolled in a government daycare center in the municipality of São José do Rio Preto, in the state of São Paulo, were collected and analyzed. Results: A total of 246 bacteria were isolated in 99% of the fecal samples; 129 were in the diarrheal group and 117 in the non-diarrheal group. Seventy- three strains of Escherichia coli were isolated, 19 of Enterobacter, one of Alcaligenes and one of Proteus. There were 14 cases of mixed colonization with Enterobacter and E. coli. Norovirus and Astrovirus were detected in children with clinical signs suggestive of diarrhea. These viruses were detected exclusively among children residing in urban areas. All fecal samples were negative for the presence of the rotavirus species A and C. The presence of Giardia lamblia, Entamoeba coli, Endolimax nana and hookworm was observed. A significant association was found between food consumption outside home and daycare center and the presence of intestinal parasites. -

Geography Summary Topography

GEOGRAPHY SUMMARY This part of the micro study informs you about the topography, infrastructure, nature and demographics of Brazil. TOPOGRAPHY The terrain of Brazil is mostly flat to rolling lowlands in north; some plains, hills, mountains, and a narrow coastal belt. Approximately 60% of the Amazon rainforest is contained in Brazil, what comes to 3.300.000 square kilometer. This rainforest is located in the Northwest of Brazil. The two maps below show some of the key characteristics like mountains, forests, cities, coastal line, etc. of Brazil. Figure 2: States and federal district of Brazil Figure 1: Major centers and points of interest Brazil has fourteen cities with more than one million inhabitants, these cities are because of historical reasons mostly located near the coast. Most of these cities can be found in figure 2. The three largest cities of Brazil are São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Salvador. (Oak, 2010) The natural resources of Brazil according to the CIA World Factbook, which uses the definition of natural resources as a country's mineral, petroleum, hydropower, and other resources of commercial importance, are: Bauxite, gold, iron ore, manganese, nickel, phosphates, platinum, tin, uranium, petroleum, hydropower and timber. (World Factbook, 2010) Brazil The Netherlands Total area: 8,514,877 sq km. 41,543 sq km Country comparison to the world: Five, slightly smaller than the 134 (Over 200 times smaller than US. Brazil) Land: 8,459,417 sq km. 33,893 sq km Water: 55,460 sq km. 7,650 sq km Number of cities with more than one 13 0 million inhabitants: Table 1: Comparative table on terrain between Brazil and the Netherlands (World Factbook, 2010) 1 INFRASTRUCTURE The land use in the North West region where the Amazon Rainforest is located is mainly used for hunting, fishing, gathering, subsistence farming and small scale lumbering. -

Convergent Agrarian Frontiers in the Settlement of Mato Grosso, Brazil

Convergent Agrarian Frontiers in the Settlement of Mato Grosso, Brazil Lisa Rausch University of Wisconsin-Madison Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies Abstract: The heterogeneity of development in the contemporary southern Amazon may be linked to different settlement experiences on the frontier. Three main types of productive settlement have been identified, including official colonization, private colonization, and spontaneous settlement, based on the differentiated motivations and resources of participants in these settlements. Not only did these different types of frontiers advance concurrently in the Amazon, but these frontiers sometimes converged in one location. The interaction of settlers from different groups sometimes created conflict, but also advanced the process of territorialization of the Amazon. This position is illustrated via a case study of one municipality at which three groups of settlers converged. Ultimately, though local popular history privileges the role of one of the three groups in bringing about the founding of the municipality and the development of a successful local economy, these achievements were only possible due to the different resources that each group brought to the settlement. Introduction he heterogeneity of the Brazilian Amazon frontier experience is just beginning to be understood. Early researchers set out structuralist expectations of accelerating resource Texploitation, capital accumulation by a relative few as land holdings were systematically consolidated, and the enlistment of the peasantry into wage labor as the agricultural frontier advanced into the Amazon.1 A linear progression toward the homogenization of Amazonian places has not occurred, however, even as highly capitalized industrial agriculture has continued to advance in the region.2 Today, the Amazon is a tapestry of highly globalized and globalizing cities, relic frontier towns, marginal extractive landscapes, and panoramas of modern, industrial- scale agricultural production with a range of landholding sizes. -

Changes in Precipitation Extremes in Brazil (Paraná River Basin)

AperTO - Archivio Istituzionale Open Access dell'Università di Torino CHANGES IN PRECIPITATION EXTREMES IN BRAZIL (PARANÁ RIVER BASIN) This is the author's manuscript Original Citation: Availability: This version is available http://hdl.handle.net/2318/153760 since 2016-07-13T11:38:28Z Published version: DOI:10.1007/s00704-015-1391-4 Terms of use: Open Access Anyone can freely access the full text of works made available as "Open Access". Works made available under a Creative Commons license can be used according to the terms and conditions of said license. Use of all other works requires consent of the right holder (author or publisher) if not exempted from copyright protection by the applicable law. (Article begins on next page) 01 October 2021 This is an author version of the contribution published on: L. Zandonadi; F. Acquaotta; S. Fratianni; J.A. Zavattini CHANGES IN PRECIPITATION EXTREMES IN BRAZIL (PARANA RIVER BASIN) THEORETICAL AND APPLIED CLIMATOLOGY (2014) DOI: 10.1007/s00704-015-1391-4 Changes in precipitation extremes in Brazil (Paraná River Basin) Leandro Zandonadi 1; Fiorella Acquaotta 2; Simona Fratianni 2 3; João Afonso Zavattini 1 1Programa de Pós-Graduação em Geografia, Universidade Estadual Paulista - UNESP, Instituto de Geociências e Ciências Exatas, Avenida 24 A, número 1515, CEP: 13506-900, Rio Claro, São Paulo, Brasil. 2Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Università di Torino - Via Valperga Caluso 35 – 10125, Torino, Italia. 3Centro di Ricerca sui Rischi Naturali in Ambiente Montano e Collinare (NatRisk), via Leonardo da Vinci 4 - 10095 Grugliasco (TO), Italia. Abstract. This research was aimed at addressing aspects related to variation in the amount of precipitation during the period from 1986 to 2011, in the Paraná River Hydrographical Basin, Brazil, for 32 meteorological stations using 11 climate indices created by the ETCCDI (Expert Team, ET, on Climate Change Detection and Indices, ETCCDI). -

SS6G3 the Student Will Explain the Impact of Location, Climate, Distribution of Natu- Ral Resources, and Population Distribution on Latin America and the Caribbean

SS6G3 The student will explain the impact of location, climate, distribution of natu- ral resources, and population distribution on Latin America and the Caribbean. a. Compare how the location, climate, and natural resources of Mexico and Venezuela affect where people live and how they trade. LOCATION, CLIMATE, AND NATURAL RESOURCES OF MEXICO Location of Mexico Mexico is the second-largest country by size and population in Latin America. It is the largest Spanish-speaking country in the world. The country is located south of the United States. On the west is the Pacific Ocean, and on the east are the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea. Mexico’s location between the Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea allows it the opportunity to trade. There are seven major seaports in Mexico. Oil and other materials from Mexico can be easily shipped around the world to ports along the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Another advantage of Mexico’s location is that it is close to the United States. Because the two countries share a border, trade is easier. Railroads and trucks can be used to ship goods. Mexico’s main trading partner is the United States. Climate of Mexico AND CANADA LATIN AMERICA LATIN Mexico has the Sierra Madre Mountains, deserts in the north, tropical beaches, plains, and plateaus. The climate varies according to the location, with some tropical areas receiving more than 40 inches of rain a year. Desert areas in the north remain dry most of the year. Most people live on the Central Plateau of Mexico in the central part of the country. -

Information to Users

Race and public policy in Brazil: Immigration, Sao Paulo and the First Republic Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Penn, David Scott, 1967- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 01:12:45 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/291872 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. -

Agriculture in Brazil's Southeast Region: Limitations and Future Challenges to Development

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics de Castro, César Nunes Working Paper Agriculture in Brazil's Southeast region: Limitations and future challenges to development Texto para Discussão, No. 1952a Provided in Cooperation with: Institute of Applied Economic Research (ipea), Brasília Suggested Citation: de Castro, César Nunes (2014) : Agriculture in Brazil's Southeast region: Limitations and future challenges to development, Texto para Discussão, No. 1952a, Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (IPEA), Brasília This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/121530 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu capa_1952a.pdf 1 29/05/2014 10:05:02 Ipea’s mission Enhance public policies that are essential to Brazilian development by producing and disseminating knowledge and by advising the state in its strategic decisions. -

The Expansion of Irrigated Agriculture in Brazil and the Potential Regional Limitations1

THE EXPANSION OF IRRIGATED AGRICULTURE IN BRAZIL AND THE POTENTIAL REGIONAL LIMITATIONS1 Angel dos Santos Fachinelli Ferrarini2 Joaquim Bento de Souza Ferreira Filho3 Santiago Vianna Cuadra4 Daniel de Castro Victoria5 Summary Regional expansion of irrigated agriculture causes a growth in food production in the country, minimizes risks for the farmer and strengthens food security for future generations. However, at the same time, it has a damaging effect on water availability, via demands for water use, which may intensify situations of microregional water scarcity6. The TERM-BR model was used to simulate expansion scenarios in irrigated areas, aiming at verifying the impact in the water use for 2025. Scenarios were adapted from the National Water Resources Plan (PNRH) and simulations were carried out for areas deemed potentially suitable for irrigation based on the Ministry of National Integration report (MI). Irrigated agriculture was separated from dry farming in terms of differential productivity. The Climatic Water Balance (CWB) was estimated for Northeastern States in order to compare regional water supply and demand. Results for the Brazil regions suggest that the greater impact on the GDP, investment and use of regional families would take place in the state of Mato Grosso, in the Midwest region of the country. The comparative result of the CWB and the TERM- BR model for states in the Northeastern region point to potential water availability problems in the states of Alagoas and Pernambuco in particular. Introduction The irrigated agriculture area has been growing constantly for the last 20 years in Brazil. The Brazilian Agricultural Census has registered a total of 1,959,810 irrigated hectares in 1985 and 4,545,532 hectares in 2006, a growth of 132% during the period. -

Brasilia, Brazil: Economic and Social Costs of Dispersion

F. de Holanda, R. Ribeiro, V. Medeiros, Brasilia: costs of dispersion, 44th ISOCARP Congress 2008 Brasilia, Brazil: economic and social costs of dispersion Introduction Brazil’s Capital, Brasilia, is a peculiar city, for better or for worse. On the plus side, the city’s form-space configuration conveys a striking image. Its generous green areas, associated with the mild climate of Brazil’s Central Plateau, affords good bioclimatic performance. On the minus side, there are serious problems concerning low urban densities, dispersion of occupied areas with no man’s land in between, and a perverse relation between location of jobs and homes (82% of formal jobs, and 44% of total jobs concentrated in an area in which only 10% of the metropolitan population live). Socioeconomic implications of these attributes are serious. Urban infrastructure is underused, intense commuting between peripheral areas and the urban core is a daily nuisance, and urban configuration does not favor transit systems. Not all is lost, though. New boroughs have occupied vacant land in between previously isolated urban areas. Densities are usually higher in these new projects – although sometimes too high, which implies diseconomies of scale. Some attempts at decentralising jobs have emerged but they have been too timid so far. This paper discusses the main attributes of the metropolis concerning the economics of urban sprawl besides analysing current trends vis-à-vis proposals of land use as presented in the most recent versions of the metropolitan development plan. Basic structure Talking about Brasília demands an initial explanation. The Brazilian Capital is a metropolis with 2,455,903 inhabitants (IBGE, 2007) within the confines of the Brazilian Federal District (henceforth FD), plus almost a million more people in urban areas which sprawl beyond the borders of the FD into the neighbouring State of Goiás.