Yields of Rubberwood Sawn Timber

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparative Study of NZ Pine & Selected SE Asian Species

(FRONT COVER) A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF NEW ZEALAND PINE AND SELECTED SOUTH EAST ASIAN SPECIES (INSIDE FRONT COVER) NEW ZEALAND PINE - A RENEWABLE RESOURCE NZ pine (Pinus radiata D. Don) was introduced to New Zealand (NZ) from the USA about 150 years ago and has gained a dominant position in the New Zealand forest industry - gradually replacing timber from natural forests and establishing a reputation in international trade. The current log production from New Zealand forests (1998) is 17 million m3, of which a very significant proportion (40%) is exported as wood products of some kind. Estimates of future production indicate that by the year 2015 the total forest harvest could be about 35 million m3. NZ pine is therefore likely to be a major source of wood for Asian wood manufacturers. This brochure has been produced to give prospective wood users an appreciation of the most important woodworking characteristics for high value uses. Sponsored by: Wood New Zealand Ltd. Funded by: New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade Written by: New Zealand Forest Research Institute Ltd. (Front page - First sheet)) NEW ZEALAND PINE - A VERSATILE TIMBER NZ pine (Pinus radiata D.Don) from New Zealand is one of the world’s most versatile softwoods - an ideal material for a wide range of commercial applications. Not only is the supply from sustainable plantations increasing, but the status of the lumber as a high quality resource has been endorsed by a recent comparison with six selected timber species from South East Asia. These species were chosen because they have similar end uses to NZ pine. -

Biosynthesis of Indigo Using Recombinant E. Coli: Development of a Biological System for the Cost Effective Production of a Large Volume Chemical

BIOSYNTHESIS OF INDIGO USING RECOMBINANT E. COLI: DEVELOPMENT OF A BIOLOGICAL SYSTEM FOR THE COST EFFECTIVE PRODUCTION OF A LARGE VOLUME CHEMICAL Alan Berry, Ph.D., Senior Scientist; Scott Battist, B.S., Ch.E., Development Engineer; Gopal Chotani, Ph.D., Ch.E., Senior Staff Scientist; Tim Dodge, M.S., Ch.E., Senior Scientist; Steve Peck, B.S., Ch.E., Development Engineer; Scott Power, Ph.D., Vice President and Research Fellow; and Walter Weyler, Ph.D., Senior Scientist Genencor International. Rochester, NY. 14618-3916. Abstract Cost-effective production of any large-volume chemical by fermentation requires extensive manipulation ofboth the production organism and the fermentation and recovery processes. We have developed a recombinant E. coli system for the production of tryptophan and several other products derived from the aromatic amino acid pathway. By linking our technology for low-cost production oftryptophan from glucose with the enzyme naphthalene dioxygenase (NOO), we have achieved an overall process for the production ofindigo dye from glucose. To successfully join these two technologies, both the tryptophan pathway and NOD were extensively modified via genetic engineering. In addition, systems were developed to remove deleterious by-products generated during the chemical oxidations leading to indigo formation. Low-cost fermentation processes were developed that utilized minimal-salts media containing glucose as the sole carbon source. Finally, economical recovery processes were used that preserved the environmental friendliness ofthe biosynthetic route to indigo. 1121 Introduction Two major problems facing the U.S. chemical industry are dependence on foreign petroleum and mounting environmental concerns and regulations (for review, see reference [1]). This has led to consideration ofbiosynthetic routes for production of aromatic compounds. -

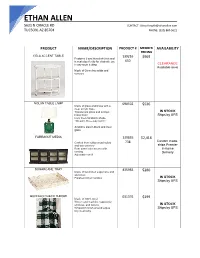

Ethan Allen 5621 N Oracle Rd

ETHAN ALLEN 5621 N ORACLE RD. CONTACT: [email protected] TUCSON, AZ 85704 PHONE: (520) 887-5621 PRODUCT NAME/DESCRIPTION PRODUCT # MEMBER AVAILABILITY PRICING CELA ACCENT TABLE 139216 $969 Features 3 oval tiered shelves and is scaled perfectly for chairside use 650 CLEARANCE in any room setting Available as-is Made of Gemelina solids and veneers NOLAN TABLE LAMP 090502 Made of glass and brass with a $536 clear acrylic base Translucent glass and antique IN STOCK brass finish Ships by UPS Ivory linen hardback shade 100-watt, three-way switch Available also in black and clear glass FARRAGUT MEDIA 139855 $2,416 Custom made, Crafted from rubberwood solids 738 ships Premier and oak veneers* Rear panel wire access with In-home venting Delivery Adjustable shelf SUGARCANE TRAY 435983 Made of laminated sugarcane and $280 aluminum Polished nickel handles IN STOCK Ships by UPS BUFFALO CHECK THROW 031376 Made of 100% wool $199 Woven and machine napped for softness, and texture IN STOCK Whipstitch finish around edges Ships by UPS Dry clean only ETHAN ALLEN 5621 N ORACLE RD. CONTACT: [email protected] TUCSON, AZ 85704 PHONE: (520) 887-5621 GREEN LIDDED JAR 430511 $184 Made of porcelain IN STOCK Hand-painted finish Removable lid Ships by UPS Not for food use BAILEY ISLAND BASKET 430507 $232 Made of seagrass and leather IN STOCK Natural finish Some variations are to be expected Ships by UPS DARK ABACA STORAGE BASKET 439833 $96 Made of madras rope IN STOCK Natural finish Ships by UPS MARA BLACK BOWL Large $89 Made of ceramic 430562A IN STOCK Black glaze Not food safe Ships by UPS Small 430562B $69 WHITE SNOWBALL GARDEN 446634A $928 • White snowball hydrangeas with IN STOCK leaves Ships by UPS • Clear glass cylinder • Container dimensions: 8" dia. -

Cop13 Analyses Cover 29 Jul 04.Qxd

IUCN/TRAFFIC Analyses of the Proposals to Amend the CITES Appendices at the 13th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties Bangkok, Thailand 2-14 October 2004 Prepared by IUCN Species Survival Commission and TRAFFIC Production of the 2004 IUCN/TRAFFIC Analyses of the Proposals to Amend the CITES Appendices was made possible through the support of: The Commission of the European Union Canadian Wildlife Service Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality, Department for Nature, the Netherlands Federal Agency for Nature Conservation, Germany Federal Veterinary Office, Switzerland Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, Dirección General para la Biodiversidad (Spain) Ministère de l'écologie et du développement durable, Direction de la nature et des paysages (France) IUCN-The World Conservation Union IUCN-The World Conservation Union brings together states, government agencies and a diverse range of non-governmental organizations in a unique global partnership - over 1 000 members in some 140 countries. As a Union, IUCN seeks to influence, encourage and assist societies throughout the world to conserve the integrity and diversity of nature and to ensure that any use of natural resources is equitable and ecologically sustainable. IUCN builds on the strengths of its members, networks and partners to enhance their capacity and to support global alliances to safeguard natural resources at local, regional and global levels. The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is the largest of IUCN’s six volunteer commissions. With 8 000 scientists, field researchers, government officials and conservation leaders, the SSC membership is an unmatched source of information about biodiversity conservation. SSC members provide technical and scientific advice to conservation activities throughout the world and to governments, international conventions and conservation organizations. -

Adding Value to Rubberwood in Malaysia

Sawmilling The rubberwood wet- off-saw timber and rotary cut veneers ready for the pressure tank Adding value to rubberwood in Malaysia In November, the Editor of Wood SA & Timber Times visited the Seng Yip Furniture Group (SYF) factory in the scenic Klang Valley located 50km from Malaysia’s capital city Kuala Lumpur. SYF manufactures a range of rubberwood products including kiln-dried sawn timber, laminated boards, furniture and smaller items ounded in 1995, Seng yip Furniture Resources Educational Association (Saldea) meetings, the stickers do Berhad’s success in shipping its products to over not appear to be quality controlled, and the stackers seem 70 countries including South Africa, saw it listed to place them at random intervals in the stacks. on the Malaysian stock exchange in 2000. In 2012, Fthe Group decided to diversify its business activities and A gigantic boiler fuelled by offcuts and sawdust provides ventured into property development. the steam for the 36 massive Chinese-manufactured kilns. The stacks of rubberwood and veneers are not weighted SYF sources its rubberwood from sawmills that process down before being dried to a maximum moisture content wood from sustainably managed plantations. The extensive of eight per cent. facilities cover more than 35 acres of industrial land, which allows the company to be a one-stop manufacturer with When the conditioning and drying schedules are complete, end-to-end capability. the wood is transported by forklift to the storage area for sorting into two lines. The dried lumber is either >> Pressure treatment 36 When the suppliers deliver the green sawn timber and rotary cut veneers, workers offload the wet-off-saw wood and then manually stack the wood onto trolleys for pressure treatment. -

(Hevea Brasiliensis) for Structural Use After the Period of Latex Extraction: a Case Study in Brazil

J Wood Sci (2015) 61:384–390 DOI 10.1007/s10086-015-1478-7 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Potential of rubberwood (Hevea brasiliensis) for structural use after the period of latex extraction: a case study in Brazil 1 1 1 Humberto de Jesus Eufrade Junior • Je´ssica Monari Ohto • Lucas Luı´s da Silva • 2 1 Hernando Alfonso Lara Palma • Adriano Wagner Ballarin Received: 13 January 2015 / Accepted: 31 March 2015 / Published online: 28 April 2015 Ó The Japan Wood Research Society 2015 Abstract In Brazil, after the cycle of latex extraction, Introduction rubber plantations are reformulated and the wood of these plantings are traditionally used as a cheap source for en- The rubber tree or Hevea brasiliensis is indigenous to the ergy purposes. Rubberwood has other uses based on the Amazon forest in Brazil [1, 2] and is commercially exploited consolidated experience in Asian countries. The aim of this for the production of latex, which is the raw material used in article was to evaluate the technological potential of the the manufacture of natural rubber. It arrived in Asia in 1877 wood of two main commercial clones of Hevea brasiliensis by way of the British Colonial Office. Initially, rubber trees in Brazil, RRIM600 and GT1, after the period of latex were grown experimentally in Sri Lanka, from where they extraction. To accomplish this objective, some physical were brought to Singapore and Malaysia [3]. and mechanical properties of wood were analyzed. The Nowadays, rubber plantations are found in many parts of clones had a basic density greater than 0.540 g cm-3, low South and Southeast Asia, Africa, and South America [4]. -

Assessment of the Properties, Utilization, and Preservation of Rubberwood (Hevea Brasiliensis): a Case Study in Malaysia

J Wood Sci (2011) 57:255–266 © The Japan Wood Research Society 2011 DOI 10.1007/s10086-011-1173-2 REVIEW ARTICLE Yi Peng Teoh · Mashitah Mat Don · Salmiah Ujang Assessment of the properties, utilization, and preservation of rubberwood (Hevea brasiliensis): a case study in Malaysia Received: July 14, 2010 / Accepted: January 14, 2011 / Published online: June 11, 2011 Abstract Rubber trees were introduced into the Malay In Malaysia, there are three major agencies responsible for Peninsula more than a century ago. The normal economical the organization of smallholdings: the Rubber Industry lifespan of a rubber tree is about 25 years, and, traditionally, Smallholder Development Authority (RISDA), the Federal rubberwood was used as fi rewood by the rural community. Land Development Authority (FELDA), and the Federal In recent decades, rubberwood has become an important Land Consolidation and Rehabilitation Authority timber for wood products, particularly in the furniture man- (FELCRA). In 1990 about 940 000 ha of smallholdings were ufacturing sector, due to its attractive features, cream color, managed by these agencies and about 240 000 ha were indi- and good working properties. Sapstain, mold, and wood- vidually owned.3 decaying fungi are serious threats to rubberwood. Conven- In rubberwood, there is no distinction between the tional chemical control has been a successful method of sapwood and the heartwood.4 It was considered that rub- preventing staining fungal growth, but the effects of these berwood contains only sapwood,5 and similar to the sap- chemicals are of concern because they create problems for woods of all timbers, is nondurable.6,7 The timber appears to the environment and public health. -

Chapter 3--Physical Properties and Moisture Relations of Wood

Chapter 3 Physical Properties and Moisture Relations of Wood William Simpson and Anton TenWolde he versatility of wood is demonstrated by a wide Contents variety of products. This variety is a result of a Appearance 3–1 spectrum of desirable physical characteristics or properties among the many species of wood. In many cases, Grain and Texture 3–1 more than one property of wood is important to the end Plainsawn and Quartersawn 3–2 product. For example, to select a wood species for a product, the value of appearance-type properties, such as texture, grain Decorative Features 3–2 pattern, or color, may be evaluated against the influence of Moisture Content 3–5 characteristics such as machinability, dimensional stability, Green Wood and Fiber Saturation Point 3–5 or decay resistance. Equilibrium Moisture Content 3–5 Wood exchanges moisture with air; the amount and direction of the exchange (gain or loss) depend on the relative humid- Sorption Hysteresis 3–7 ity and temperature of the air and the current amount of water Shrinkage 3–7 in the wood. This moisture relationship has an important Transverse and Volumetric 3–7 influence on wood properties and performance. This chapter discusses the physical properties of most interest in the Longitudinal 3–8 design of wood products. Moisture–Shrinkage Relationship 3–8 Some physical properties discussed and tabulated are influ- Weight, Density, and Specific Gravity 3–11 enced by species as well as variables like moisture content; Working Qualities 3–15 other properties tend to be independent of species. The thor- oughness of sampling and the degree of variability influence Decay Resistance 3–15 the confidence with which species-dependent properties are Thermal Properties 3–15 known. -

Elaboration of Rubberwood Quality: Toward a Sustainable Sawn Wood Production

Elaboration of Rubberwood quality: Toward a sustainable sawn wood production ******************************** Jean GERARD Forest Products Programme, CIRAD-Forêt, Montpellier Introduction Even if the Southeast Asian countries have overcome most of the technical problems in processing and utilization by over the past 25 years, and the timber successfully marketed internationally, enhanced value of Rubberwood for solid wood products remains typically limited by several factors. These factors have various origins related to intrinsic wood quality, but also use of unsuited processes, even if appropriated ones exists, and weak knowledge of the markets and the needs of the consumers. It should be observed that finding the optimum ways to develop and improve utilization of Rubberwood by sawing (or eventually peeling) is also a recurring problem for the main part of the forest species used in plantation for timber production (especially in tropical areas). Some of these technical aspects are going to be hereafter developed. The main sources of wood variations and factors at the origin of wood quality elaboration will be specifically highlighted. Discussions will be further enlarged to possible application of ecocertification and ecoprocess systems, presently emerging for tropical wood species, to Rubberwood sector. Elaboration of Wood Quality Wood manufacturers that are using sawn products from primary processing industry mainly look for stability of their supplying; this stability concerns volumes of wood to feed the factories but also the homogeneousness and appropriate quality of wood in order to satisfy customers needs. Unevenness of supplying can deeply disrupt industrial organization, sometimes endangering the survival of the enterprise. As a matter of fact, marketability of primary processing Rubberwood products closely depends on the level quality and the variability of their quality, taking into account that wood quality can be defined only in appropriateness with the end-products and the constraints their uses involve. -

Client's Name

BASELINE STUDY 5, THAILAND: Overview of Forest Law Enforcement,Governance and Trade July 2011 Regional Support Programme for the EU FLEGT Action Plan in Asia Background The European Commission (EC) published a Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (FLEGT) Action Plan in 2003. FLEGT aims not simply to reduce illegal deforestation, but in promoting good forest governance, aims to contribute to poverty eradi- cation and sustainable management of natural resources. The European Forest Institute (EFI), an international research organisation with its headquarters in Finland, conducts, advo- cates and facilitates forest research networking at the pan-European level. Under its Policy & Governance programme, the EFI assists in the EU’s implementation of the FLEGT Action Plan. In 2007, the EU FLEGT Facility was established, hosted and man- aged by the EFI. The Facility (i) supports the bilateral process between the EU and tropical producing countries towards signing and implementing “Voluntary Partnership Agreements” (VPAs) under the FLEGT Action Plan, and (ii) executes the regional sup- port programme for the EU FLEGT Action Plan in Asia. The FLEGT Asia Regional Office (FLEGT Asia) of the EFI’s EU FLEGT Facility was formally established in October 2009. FLEGT Asia seeks to collaborate and build synergies with existing regional initiatives and partners in Asia. The EU FLEGT Facility is managed and implemented by the EFI in close collaboration with the EU. Goal of FLEGT Asia The goal of the FLEGT Asia Regional Programme is the promotion of good forest governance, contributing to poverty eradica- tion and sustainable management of natural resources in Asia, through direct support of the implementation of the EU’s FLEGT Action Plan. -

Forest Products Forest Annual Market Annual Review 2014-2015

UNECE Forest Products Forest Annual MarketAnnual Review 2014-2015 UNECE Forest Products - Annual Market Review 2014-2015 UNITED NATIONS UNECE Forest Products Annual Market Review 2014-2015 II UNECE/FAO Forest Products Annual Market Review, 2014-2015 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Data for the Commonwealth of Independent States is composed of these twelve countries: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Republic of Moldova, Russian Federation, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan. DISCLAIMER The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or carry the endorsement of the United Nations. ABSTRACT The Forest Products Annual Market Review 2014-2015 provides a comprehensive analysis of markets in the UNECE region and reports on the main market influences outside the UNECE region, using the best-available data from diverse sources. It covers the range of products from the forest to the end-user: from roundwood and primary-processed products to value-added products and those used in housing. Statistics-based chapters analyse the markets for wood raw materials, sawn softwood, sawn hardwood, wood- based panels, paper, paperboard and woodpulp. Other chapters analyse policies, institutional forestland ownership and its effects on forest products markets, and markets for wood energy. The Review highlights the role of sustainable forest products in international markets. -

China Section 301 Tariff Exclusion Requests Granted Lists 1, 2, 3, and 4A Combined

China Section 301 Tariff Exclusion Requests Granted Lists 1, 2, 3, and 4A Combined Updated: 10/5/2020 New HTSUS Date Exclusion Date Exclusion Date Extension Revised Expiration List # HTS Code Product Description Subheading Granted Expires Granted Date List 3 0304.61.0000 Tilapias, frozen, each weighing not more than 115 g 9903.88.43 3/20/2020 8/7/2020 Extension Not Granted List 3 0304.72.5000 Haddock Fillets, Frozen, Others 9903.88.56 12/17/2019 8/7/2020 8/6/2020 12/31/2020 List 3 0304.83.1015 Sole Fillets, Skinned, Frozen Blocks Weighing Over 4.5 Kg Each, Imported To Be Minced, Ground Or Cut Into 9903.88.56 12/17/2019 8/7/2020 8/6/2020 12/31/2020 Pieces Of Uniform Weights And Dimensions List 3 0304.83.1020 Flounder Fillets, Skinned, Frozen Blocks Weighing Over 4.5 Kg Each, Imported To Be Minced, Ground Or Cut 9903.88.56 12/17/2019 8/7/2020 8/6/2020 12/31/2020 Into Pieces Of Uniform Weights And Dimensions List 3 0304.83.5015 Alaskan sole (yellowfin, rock or flathead), frozen in blocks, in cases with net weight of more than 4.5 kg 9903.88.56 2/3/2020 8/7/2020 8/6/2020 12/31/2020 List 3 0304.83.5015 Sole fillets, individually frozen, each fillet weighing more than 50 g but less than 150 g 9903.88.56 2/3/2020 8/7/2020 8/6/2020 12/31/2020 List 3 0304.83.5020 Alaskan plaice, frozen in blocks, in cases each with net weight of more than 4.5 kg 9903.88.56 2/3/2020 8/7/2020 8/6/2020 12/31/2020 List 3 0304.83.5020 Individually frozen fillets of flounder, including Arrowtooth Flounder (Atheresthes stomias) and Kamchatka 9903.88.56 2/3/2020 8/7/2020