Playing with Genesis: Sonship, Liberty, and Primogeniture in Sense and Sensibility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colony and Empire, Colonialism and Imperialism: a Meaningful Distinction?

Comparative Studies in Society and History 2021;63(2):280–309. 0010-4175/21 © The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Society for the Comparative Study of Society and History doi:10.1017/S0010417521000050 Colony and Empire, Colonialism and Imperialism: A Meaningful Distinction? KRISHAN KUMAR University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA It is a mistaken notion that planting of colonies and extending of Empire are necessarily one and the same thing. ———Major John Cartwright, Ten Letters to the Public Advertiser, 20 March–14 April 1774 (in Koebner 1961: 200). There are two ways to conquer a country; the first is to subordinate the inhabitants and govern them directly or indirectly.… The second is to replace the former inhabitants with the conquering race. ———Alexis de Tocqueville (2001[1841]: 61). One can instinctively think of neo-colonialism but there is no such thing as neo-settler colonialism. ———Lorenzo Veracini (2010: 100). WHAT’ S IN A NAME? It is rare in popular usage to distinguish between imperialism and colonialism. They are treated for most intents and purposes as synonyms. The same is true of many scholarly accounts, which move freely between imperialism and colonialism without apparently feeling any discomfort or need to explain themselves. So, for instance, Dane Kennedy defines colonialism as “the imposition by foreign power of direct rule over another people” (2016: 1), which for most people would do very well as a definition of empire, or imperialism. Moreover, he comments that “decolonization did not necessarily Acknowledgments: This paper is a much-revised version of a presentation given many years ago at a seminar on empires organized by Patricia Crone, at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton. -

Guidance on the Use of Royal Arms, Names and Images

GUIDANCE ON THE USE OF ROYAL ARMS, NAMES AND IMAGES 1 The following booklet summarises the legal position governing the use, for commercial purposes, of the Royal Arms, Royal Devices, Emblems and Titles and of photographs, portraits, engravings, effigies and busts of The Queen and Members of the Royal Family. Guidance on advertising in which reference is made to a Member of the Royal Family, and on the use of images of Members of the Royal Family on articles for sale, is also provided. The Lord Chamberlain’s Office will be pleased to provide guidance when it is unclear as to whether the use of “Arms” etc., may give the impression that there is a Royal connection. 2 TRADE MARKS Section 4 (1) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 states: “A trade mark which consists of or contains – (a) the Royal arms, or any of the principal armorial bearings of the Royal arms, or any insignia or device so nearly resembling the Royal arms or any such armorial bearing as to be likely to be mistaken for them or it, (b) a representation of the Royal crown or any of the Royal flags, (c) a representation of Her Majesty or any Member of the Royal Family, or any colourable imitation thereof, or (d) words, letters or devices likely to lead persons to think that the applicant either has or recently has had Royal patronage or authorisation, shall not be registered unless it appears to the registrar that consent has been given by or on behalf of Her Majesty or, as the case may be, the relevant Member of the Royal Family.” The Lord Chamberlain's Office is empowered to grant the consent referred to in Section 4(1) on behalf of Her Majesty The Queen. -

Bundle of S Cks—Real Property Rights and Title Insurance Coverage

Bundle of Scks—Real Property Rights and Title Insurance Coverage Marc Israel, Esq. What Does Title Insurance “Insure”? • Title is Vested in Named Insured • Title is Free of Liens and Encumbrances • Title is Marketable • Full Legal Use and Access to Property Real Property Defined All land, structures, fixtures, anything growing on the land, and all interests in the property, which may include the right to future ownership (remainder), right to occupy for a period of +me (tenancy or life estate), the right to build up (airspace) and drill down (minerals), the right to get the property back (reversion), or an easement across another's property.” Bundle of Scks—Start with Fee Simple Absolute • Fee Simple Absolute • The Greatest Possible Rights Insured by ALTA 2006 Policy • “The greatest possible estate in land, wherein the owner has the right to use it, exclusively possess it, improve it, dispose of it by deed or will, and take its fruits.” Fee Simple—Lots of Rights • Includes Right to: • Occupy (ALTA 2006) • Use (ALTA 2006) • Lease (Schedule B-Rights of Tenants) • Mortgage (Schedule B-Mortgage) • Subdivide (Subject to Zoning—Insurable in Certain States) • Create a Covenant Running with the Land (Schedule B) • Dispose Life Estate S+ck • Life Estate to Person to Occupy for His Life+me • Life Estate can be Conveyed but Only for the Original Grantee’s Lifeme • Remainderman—Defined in Deed • Right of Reversion—Defined in Deed S+cks Above, On and Below the Ground • Subsurface Rights • Drilling, Removing Minerals • Grazing Rights • Air Rights (Not Development Rights—TDRs) • Canlever Over a Property • Subject to FAA Rules NYC Air Rights –Actually Development Rights • Development Rights are not Real Property • Purely Statutory Rights • Transferrable Development Rights (TDRs) Under the NYC Zoning Resoluon and Department of Buildings Rules • Not Insurable as They are Not Real Property Title Insurance on NYC “Air Rights” • Easement is an Insurable Real Property Interest • Easement for Light and Air Gives the Owner of the Merged Lots Ability to Insure. -

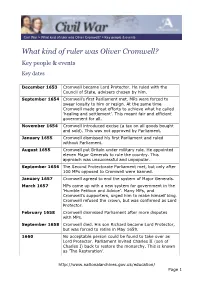

What Kind of Ruler Was Oliver Cromwell? > Key People & Events

Civil War > What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? > Key people & events What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? Key people & events Key dates December 1653 Cromwell became Lord Protector. He ruled with the Council of State, advisers chosen by him. September 1654 Cromwell’s first Parliament met. MPs were forced to swear loyalty to him or resign. At the same time Cromwell made great efforts to achieve what he called ‘healing and settlement’. This meant fair and efficient government for all. November 1654 Cromwell introduced excise (a tax on all goods bought and sold). This was not approved by Parliament. January 1655 Cromwell dismissed his first Parliament and ruled without Parliament. August 1655 Cromwell put Britain under military rule. He appointed eleven Major Generals to rule the country. This approach was unsuccessful and unpopular. September 1656 The Second Protectorate Parliament met, but only after 100 MPs opposed to Cromwell were banned. January 1657 Cromwell agreed to end the system of Major Generals. March 1657 MPs came up with a new system for government in the ‘Humble Petition and Advice’. Many MPs, and Cromwell’s supporters, urged him to make himself king. Cromwell refused the crown, but was confirmed as Lord Protector. February 1658 Cromwell dismissed Parliament after more disputes with MPs. September 1658 Cromwell died. His son Richard became Lord Protector, but was forced to retire in May 1659. 1660 No acceptable person could be found to take over as Lord Protector. Parliament invited Charles II (son of Charles I) back to restore the monarchy. This is known as ‘The Restoration’. -

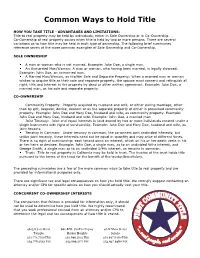

Common Ways to Hold Title

Common Ways to Hold Title HOW YOU TAKE TITLE - ADVANTAGES AND LIMITATIONS: Title to real property may be held by individuals, either in Sole Ownership or in Co-Ownership. Co-Ownership of real property occurs when title is held by two or more persons. There are several variations as to how title may be held in each type of ownership. The following brief summaries reference seven of the more common examples of Sole Ownership and Co-Ownership. SOLE OWNERSHIP A man or woman who is not married. Example: John Doe, a single man. An Unmarried Man/Woman: A man or woman, who having been married, is legally divorced. Example: John Doe, an unmarried man. A Married Man/Woman, as His/Her Sole and Separate Property: When a married man or woman wishes to acquire title as their sole and separate property, the spouse must consent and relinquish all right, title and interest in the property by deed or other written agreement. Example: John Doe, a married man, as his sole and separate property. CO-OWNERSHIP Community Property: Property acquired by husband and wife, or either during marriage, other than by gift, bequest, devise, descent or as the separate property of either is presumed community property. Example: John Doe and Mary Doe, husband and wife, as community property. Example: John Doe and Mary Doe, husband and wife. Example: John Doe, a married man Joint Tenancy: Joint and equal interests in land owned by two or more individuals created under a single instrument with right of survivorship. Example: John Doe and Mary Doe, husband and wife, as joint tenants. -

Why Did Britain Become a Republic? > New Government

Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Why did Britain become a republic? Case study 2: New government Even today many people are not aware that Britain was ever a republic. After Charles I was put to death in 1649, a monarch no longer led the country. Instead people dreamed up ideas and made plans for a different form of government. Find out more from these documents about what happened next. Report on the An account of the Poem on the arrest of setting up of the new situation in Levellers, 1649 Commonwealth England, 1649 Portrait & symbols of Cromwell at the The setting up of Cromwell & the Battle of the Instrument Commonwealth Worcester, 1651 of Government http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/ Page 1 Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Case study 2: New government - Source 1 A report on the arrest of some Levellers, 29 March 1649 (Catalogue ref: SP 25/62, pp.134-5) What is this source? This is a report from a committee of MPs to Parliament. It explains their actions against the leaders of the Levellers. One of the men they arrested was John Lilburne, a key figure in the Leveller movement. What’s the background to this source? Before the war of the 1640s it was difficult and dangerous to come up with new ideas and try to publish them. However, during the Civil War censorship was not strongly enforced. Many political groups emerged with new ideas at this time. One of the most radical (extreme) groups was the Levellers. -

Common Ways of Holding Title to Real Property

NORTH AMERICAN TITLE COMPANY Common Ways of Holding Title to Real Property Tenancy in Common Joint Tenancy Parties Any number of persons. Any number of persons. (Can be husband and wife) (Can be husband and wife) Division Ownership can be divided into any number of Ownership interests cannot be divided. interests, equal or unequal. Title Each co-owner has a separate legal title to his There is only one title to the entire property. undivided interest. Possession Equal right of possession. Equal right of possession. Conveyance Each co-owner’s interest may be conveyed Conveyance by one co-owner without the separately by its owner. others breaks the joint tenancy. Purchaser’s Status Purchaser becomes a tenant in common with Purchaser becomes a tenant in common with other co-owners. other co-owners. Death On co-owner’s death, his interest passes by On co-owner’s death, his interest ends and will or intestate succession to his devisees or cannot be willed. Surviving joint tenants heirs. No survivorship right. own the property by survivorship. Successor’s Status Devisees or heirs become tenants in common. Last survivor owns property in severalty. Creditor’s Rights Co-owner’s interest may be sold on execution Co-owner’s interest may be sold on execu- sale to satisfy his creditor. Creditor becomes a tion sale to satisfy creditor. Joint tenancy is tenant in common. broken, creditor becomes tenant in common. Presumption Favored in doubtful cases. None. Must be expressly declared. This is provided for informational puposes only. Specific questions for actual real property transactions should be directed to your attorney or C.P.A. -

Staging Power in Tudor and Stuart English History Plays: History, Political Thought, and the Redefinition of Sovereignity Kristin M.S

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Bookshelf 2015 Staging Power in Tudor and Stuart English History Plays: History, Political Thought, and the Redefinition of Sovereignity Kristin M.S. Bezio University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/bookshelf Part of the Leadership Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bezio, Kristin M.S. Staging Power in Tudor and Stuart English History Plays: History, Political Thought, and the Redefinition of Sovereignty. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2015. NOTE: This PDF preview of Staging Power in Tudor and Stuart English History Plays: History, Political Thought, and the Redefinition of Sovereignity includes only the preface and/or introduction. To purchase the full text, please click here. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bookshelf by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Staging Power in Tudor and Stuart English History Plays History, Political Thought, and the Redefinition of Sovereignty KRISTIN M.S. BEZIO University ofRichmond, USA LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND VIRGINIA 23173 ASHGATE Introduction Of Parliaments and Kings: The Origins of Monarchy and the Sovereign-Subject Compact in the English Middle Ages (to 1400) The purpose of this study is to examine the intersection between early modem political thought, the history that produced the late Tudor and early Stuart monarchies, and the critical interrogation of both taking place on the public theatrical stage. The plays I examine here are those which rely on chronicle histories for their source materials; are set in England, Scotland, or Wales; focus primarily on governance and sovereignty; and whose interest in history is didactic and actively political. -

What's Wrong with a Federal Inheritance Tax? Wendy G

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship Spring 2014 What's Wrong with a Federal Inheritance Tax? Wendy G. Gerzog University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Estates and Trusts Commons, Taxation-Federal Commons, Taxation-Federal Estate and Gift ommonC s, and the Tax Law Commons Recommended Citation What's Wrong with a Federal Inheritance Tax?, 49 Real Prop. Tr. & Est. L.J. 163 (2014-2015) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHAT'S WRONG WITH A FEDERAL INHERITANCE TAX? Wendy C. Gerzog* Synopsis: Scholars have proposed a federal inheritance tax as an alternative to the current federal transfer taxes, but that proposal is seriously flawed. In any inheritance tax model, scholars should expect to see significantly decreased compliance rates and increased administrative costs because, by focusing on the transferees instead of on the transferor, an inheritance tax would multiply the number oftaxpayers subject to the tax. This Article reviews common characteristics ofexisting inheritance tax systems in the United States and internationally-particularly in Europe. In addition, the Article analyzes the novel Comprehensive Inheritance Tax (CIT) proposal, which combines some elements of existing inheritance tax systems with some features ofthe current transfer tax system and delivers the CIT through the federal income tax system. -

Sense and Sensibility Study Guide Is Aimed at Students of A’ Level Film and Communication and English

TEACHERS’ NOTES The Sense and Sensibility study guide is aimed at students of A’ Level Film and Communication and English. It may also be suitable for some students of GCSE Media Studies and English. SYNOPSIS When Henry Dashwood dies unexpectedly, his estate must pass by law to his son from his first marriage, John and wife Fanny. But these circumstances leave Mr. Dashwood’s current wife and daughters Elinor, Marianne and Margaret, without a home and barely enough money to live on. ©Film Education 1 As Elinor and Marianne struggle to find romantic fulfilment in a society obsessed with financial and social status, they must learn to mix sense with sensibility in their dealings with both money and men. Based on Jane Austen’s first novel, Sense and Sensibility marks the first big-screen adaptation of this classic romantic comedy. Directed by Ang Lee. Certificate: U. Running rime: 135 mins. INTRODUCTION “Jane Austen? Aren’t her novels just old-fashioned romantic stories about love amongst the rich and lazy?” To many people, including students of English Literature, there is a problem penetrating the ‘Mills and Boon’ romantic veneer of Jane Austen's plots to find the subtle analysis of social and moral behaviour that teachers and critics claim is beneath the surface. Even after studying her novels, many students find Austen’s world remote and perhaps rather trivial. READING NOVELS - READING FILMS - READING TEXTS The fact n that there are many film and television adaptations of Jane Austen's novels and this itself is a mark of her popularity as well as her skill as a writer. -

Female Psyche and Empowerment of Jane Austen and Lakshmi's Select

International Journal of Research (IJR) Vol-1, Issue-9 October 2014 ISSN 2348-6848 Female Psyche and Empowerment o f Jane Austen and Lakshmi’s Select Novels Dr. V. Asokkumar, M.A., M.Phil, Ph.D., Associate Professor of English, E.R.K.Arts & Science College, Erumaiyampatti – 636 905 Pappireddipatti (Tk), Dharmapuri (Dt) INDIA. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT cultures. A nostalgic representative of the th This article aims at analyzing the classical 18 century, Jane Austen was occidental and oriental works of literary poised more in reason rather than art with special reference to the select emotion. Jane Austen wrote about what novels of Jane Austen and Lakshmi. she had experienced in her life. Hers is a Women novelists have a strong foundation world of the country middle class people. of social awareness and concentration on She deals with various aspects of love and family welfare. This article interprets Jane marriage and views them calmly and Austen’s three novels - Sense and dispassionately. She distrusts emotion and Sensibility Pride and Prejudice and describes it only by implication. Mansfield park and two of Lakshmi’s Lakshmi from Tamilnadu is a novels - Penn Manam and Oru Kaveriyai strong flavour of Tamil literature and Pola. This study except the first and the culture in her novels. She has a strong last are significantly titled implying the perception regarding the treatment of different strategies of female predicaments women in the Tamil society and is very amidst which Jane Austen and Lakshmi bold in portraying their emotions have set afloat their women characters kaleidoscopically. -

“—A Very Elegant Looking Instrument—” Musical Symbols And

('-a very elegant looking instrumgnl-"' Musical Symbols and Substance in Films of Jane Austen's Novels KATHRYN L. SHANKS LIBIN Department of Music, Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, NY 12604-0018 The recent flowering of Jane Austen novels on television and film raises fascinating issues of interpretation and authenticity. Great efforts have been made to recreate believable nineteenth-century backgrounds; the houses, furniture, costumes, jewelry, and so forth all show scrupulous historical research and attention to detail. origi- nal musical instruments have likewise been featured in these new visual versions of Jane Austen's texts. However, it is relatively easy to flt an attractive old instrument into its period setting; finding the right tone with the music itself is'a much more complicated problem, und fe* of the film makers involved with Austen's works have demonstrated perfect pitch in this matter. For the problem consists not simply of finding the right musical symbols: the proper instru- ments, or sound, or representative pieces of music that Jane Austen might have known; but of grappling, as well, with the musical substance ofher novels. In certain instances music is an essential plot device; and musical performance reveals key aspects of personality in many of her characters. Jane Austen herself faithfully practiced the piano, and copied out music into notebooks for her own use. Indeed, her music notebooks show that she was an accomplished musician, possessing a firm grasp of the rules and implications of musical notation and, not iurpiisingly, an elegant copyist's hand.' The mere existence of these notibooks, which represent countless hours of devoted labor as well as pleasure, shows the central role that music played in Austen's own life.