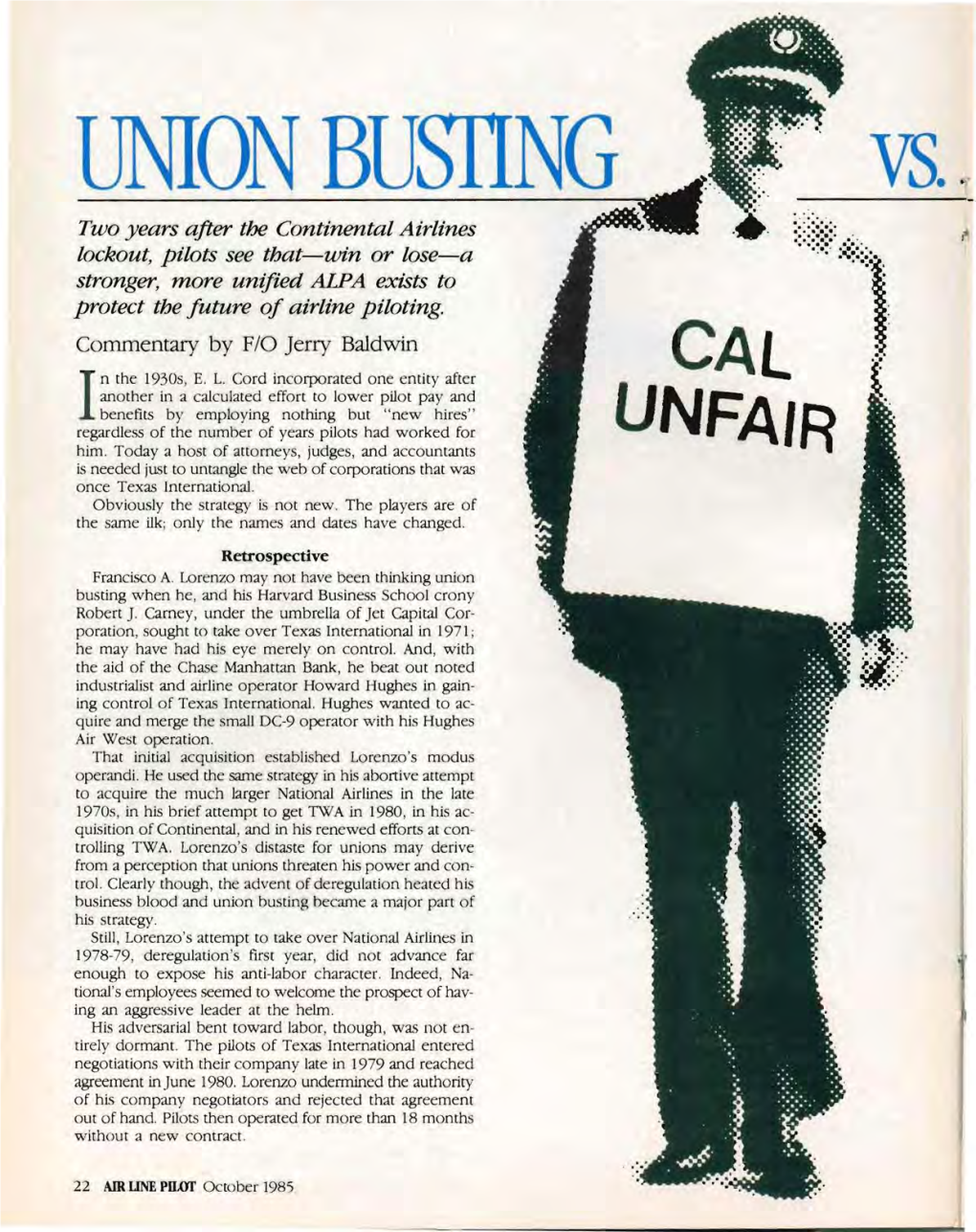

Union Busting Vs Unionism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Continental Air Lines 컨티넨탈항공

Continental Air Lines 컨티넨탈항공 국 적 : United States / 미국 코 드 : CO / COA 콜사인 : CONTINENTAL 기준일: 2008.12.31 ◎ 개요 ▶ 주소 : 1600 Smith Street, Houston, Texas 77002, United States ▶ 전화 : (+1 713) 324 50 00 ▶ 팩스 : (+1 713) 324 20 87 ▶ 홈페이지 : http://www.continental.com ◎ 역사 ▶ 1934년 7월에 운항을 시작하여 미국의 규제완화법이 발효된 이후에 바로 텍사스에어(Texas Air)와 의 합병으로 Texas Air Corporation이 인수이전까지 미국내에서 주요한 항공사였다. 이후, 이 항공사는 1993년의 자본구조조정 이전에 파산보호법 제11조에 따른 보호기간을 보냈으며 이 후 1995년까지 에어캐나다(Air Canada)와 파트너쉽의 관계인 Air Partners는 1995년까지 조정을 맡았 다. 자본의 재구성에 이어서, 노선망은 국제적으로는 Continental Micronesia항공을 통해서 그리고 휴스턴, 뉴어크(뉴욕) 및 클리블랜드의 주요 허브주변으로 합리화되었다. 콘티넨탈은 수많은 항공사들과 마케팅 협약을 체결하였다. 콘티넨탈과 노스웨스트 항공간의 동맹으로, 노스웨스트는 14%의 컨티넨탈 보통주와 51%의 투표권을 인수하였다. 콘티넨탈과 노스웨스트는 2000년 11월에 노스웨스트가 보유하고 있는 주식을 콘티넨탈에 매각하는것과 동맹계약을 2025년까지 연장하는것에 관한 최종계약을 실행하였다. 항공안정화(Air Transport Safety and System Stabilisation Act)법령에 의거, 이 항공사는 4억1천7백 만달러와 특별부가금 1억4천6백만달러를 지원 받았다. 2001년의 9·11사건 이후, 이 항공사는 수용력과 종업원수를 감축하였다. 2003년 교통산업의 하락이 있자, 이 항공사는 노선망을 계속 정비하고 2003년 7월에 ExpressJet Holdings (dba Continental Express)에 있는 지분을 다시 익스프레스젯(ExpressJet)에 매각하는 것에 동의하였다. 이 항공사는 현재 익스프레스젯에 있는 모든 지분을 매각하였다. 특별 아이템에 힘입어 2003년에 소폭의 순이익을 기록하였지만 재정상태를 개선하기위한 비용절감 노 력은 계속되고 있다. 2004년 9월, 이 항공사는 스카이팀 동맹의 회원이 되었다. 2004년 11월, 이 항공사는 자체 수입과 비용절감 목표치를 11억달러에서 16억달러로 확대하였다. 모든 자격있는 종업원들에게 주당 11.89달러의 옵션행사 가격과 함께 약 8백7십만주의 스톡옵션이 발행되었 다. 이 항공사는 보잉 항공기에 대한 새로운 주문을 하였으며 국제노선망을 확대하고 있다. -

CED-82-33 Impact on Federal Government If the Combined

UNITED STATES GENERAL ACCOUNTING OFFICE WASHINGTON, D.C. 20548 COMMUNITY AND ECONOMIC 117500 DEVELOPMENT DIVISION B-206097 The Honorable Mark 0. Hatfield RELEASED United States Senate Subject: Impact on the Federal Government if the Combined Continental Airlines and Texas International Airlines Fail to Meet Their Financial Obligations ' (CED-82-33) This report responds to your letter of October 7, 1981, requesting certain information on the potential financial loss to the Federal Government if the combined Continental Airlines and Texas International Airlines fail to meet their financial obligations. The report addresses the subjects raised in your letter--essential air service to the Pacific; aircraft loan guarantees; potential revenue loss to the Treasury; and the Airline Employee Protection Program. We reviewed Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) documents con- cerning essential air service to the Pacific and the airline employee protection program; Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) documents concerning the aircraft loan guarantee pro- gram; and Department of Labor documents concerning the airline employee protection program. We interviewed CAB, FAA, and Labor officials in Washington, D.C., concerning these programs and had telephone conversations with Continental Airlines and its Washington counsel, Hydeman, Mason, Burzio, and Lloyd, con- cerning taxes paid or collected by Continental and concerning Pacific air service. We were not requested to make any judg- ments on the financial viability of the merged airline. Our review was made in accordance with GAO's current "Standards for Audit of Governmental Organizations, Programs, Activities, and Functions." ESSENTIAL AIR SERVICE TO THE PACIFIC The Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 (Public Law 95-504) guarantees essential air transportation for any point in the United States to which any carrier (1) is providing service pursuant to a certificate issued under section 401 of the (341037) (5-a (--y33 63 . -

Airline Mergers, Acquisitions and Bankruptcies: Will the Collective Bargaining Agreement Survive Jonni Walls

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 56 | Issue 3 Article 7 1991 Airline Mergers, Acquisitions and Bankruptcies: Will the Collective Bargaining Agreement Survive Jonni Walls Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Jonni Walls, Airline Mergers, Acquisitions and Bankruptcies: Will the Collective Bargaining Agreement Survive, 56 J. Air L. & Com. 847 (1991) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol56/iss3/7 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. AIRLINE MERGERS, ACQUISITIONS AND BANKRUPTCIES: WILL THE COLLECTIVE BARGAINING AGREEMENT SURVIVE? JONNI WALLS I. INTRODUCTION AIRLINE DEREGULATION has produced a record number of mergers and bankruptcies in the airline in- dustry, turning the industry into a "national oligopoly."' Since deregulation, over 200 scheduled carriers have gone out of business, mainly because of mergers, acquisi- tions and bankruptcies. 2 As a result, the top eight carri- ers control over 90 percent of the market. Since 1978 more than 120 airlines have filed various types of bank- ruptcy proceedings.' The flurry of merger activity that began almost immediately upon enactment of deregula- tion 5 continues to be extremely vigorous. Between 1985 and 1987 over twenty-five mergers took place, and 1986 1 P. DEMPSEY, THE SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CONSEQUENCES OF DEREGULATION 81 (1989); Dempsey, Airline Deregulation and Laissez Faire Mythology: Economic Theory in Turbulence, 56J. AIR L. & CoM. -

Death of Eastern: How One Man Destroyed an Airline

Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research Volume 9 Number 3 JAAER Spring 2000 Article 3 Spring 2000 Death of Eastern: How One Man Destroyed an Airline Joseph G. Ferrante Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/jaaer Scholarly Commons Citation Ferrante, J. G. (2000). Death of Eastern: How One Man Destroyed an Airline. Journal of Aviation/ Aerospace Education & Research, 9(3). Retrieved from https://commons.erau.edu/jaaer/vol9/iss3/3 This Forum is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ferrante: Death of Eastern: How One Man Destroyed an Airline FORUM Joseph G. Ferrante In 1986, when Frank Lorenzo took over Eastern Airlines, the country's third largest carrier was in decline: its route structure was inherently weak, its costs were sky high, and its stiff-necked labor unions fought with each other almost as much as they fought management. To rnzmy in corporate America, Lorenzo seemed just the man to whip Eastern back into shape. Lorenzo, with the help of Michael Milken and Drexel Burnham Lambert 's junk bond machine, built his tiny Texas Air Corporation into an empire. Indeed, with the addition of Eastern to Continental, Frontier, and People Express airlmes, Lorenzo controlled the largest airline in the country, nylng more than a fifth of the nation's air passengers on his planes. Larenzo has been characterized as a ruthless empire builder, who uses a seemingly simple formula of slashing costs and offering lower fares. -

RCED-91-101 Airline Competition

GAO April I!f!I 1 AIRLINE COMPETITION Effects of Airline Market Concentration and Barriers to Entry on Airfares - 143865 ___I--__... ..-.__ __.- ._.._.. ._._ ...-.__ .-.. I- --.-..__..-.___ -_.._-.- .^...._ _.__- .._.. _- ___. -I-~ -~~- United States General Accounting Office GAO Washington, D.C. 20648 Resources, Community, and Economic Development Division B-242870 April 26, 1991 The Honorable Jack Brooks Chairman, Committee on the Judiciary House of Representatives The Honorable JamesL. Oberstar Chairman, Subcommitteeon Aviation Committee on Public Works and Transportation House of Representatives The Honorable John C. Danforth Ranking Minority Member Committee on Commerce,Science, and Transportation United States Senate Rising fares on certain routes and a wave of mergers and bankruptcies have raised concernsthat the airline industry has becomeless competi- tive than envisioned when the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 was passed.This report is one in a series of GAO reviews on competition in the nation’s airline industry. (SeeRelated GAO Products.) In an earlier report, we identified the presenceof factors that inhibit airlines from , entering a market, often called “barriers to entry,” and discussedtheir potential effects on competition.1This report presents estimates of how several other factors, such as an airline’s market share and airport con- gestion, as well as barriers to entry, affect air fares. It also discussesthe policy implications of our analysis. To conduct this analysis, we developed an econometricmodel that exam- ines how several competitive conditions influence an airline’s fare and market share on a route. The model also includes other factors, such as distance and traffic volume, that were consideredlikely to influence fares and market shares. -

Choice of Law in Air Disaster Cases: Complex Litigation Rules and the Common Law James A

Louisiana Law Review Volume 54 | Number 4 The ALI's Complex Litigation Project March 1994 Choice of Law in Air Disaster Cases: Complex Litigation Rules and the Common Law James A. R. Nafziger Repository Citation James A. R. Nafziger, Choice of Law in Air Disaster Cases: Complex Litigation Rules and the Common Law, 54 La. L. Rev. (1994) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol54/iss4/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Choice of Law in Air Disaster Cases: Complex Litigation Rules and the Common Law James A. R. Nafziger" The Complex Litigation Project of the American Law Institute includes a significant scheme of choice-of-law rules in state created actions.' The core provision, Section 6.01 ("Mass Torts"), adopts a "single state" approach to govern consolidated claims, by which one state's tort law is to be applied to all similar claims against each defendant.2 Three sets of significant contacts 3 enable courts to identify states4 whose policies would be furthered by application of their laws. In selecting among the laws of two or more interested states, the court is to be guided by a prioritized list of preference rules.5 Two concluding subsections 6 provide safety valves. The first safety valve permits a court to avoid an unfair surprise or arbitrary result by selecting a more appropriate law than the prescribed analysis would indicate. -

July 9, 1990 Office of the General Counsel Federal Election

LAW OFFICES VERNER, LIIPFERT. BERNHARD. McPHERSON AND HAND CHARTCRCO JAMES M. VERNER* JULIA R. RICHARDSON SUITE 7OO TERRENCE J. MOCARTIN MARK R. LEWIS EUGENE T. UIPFERT RUSSELL E. POMMER 9OI-I5TH STREET. N.W. PAUL E. NORDSTROM SHERRI L. THORNTON* EMERITUS GEORGE M. FCOTE. JR.* SHERRY A. OUIRK THERESA I. ZOLCT* BUEL WHITE* ^ WASHINGTON. O.C. 2OOO5-23OI DEAN R. BRENNER JOHNJ.ACKELL* BERL BERNHARO WILUAM F. ROEOER. JR.** FRANCES C OCLAURENTIS SCOTT K. DAINES HARRY MCPHERSON ROY O. BOWMAN (2O2) 37I-6OOO JOHN A. MENKC DAVID P. HENDEL LLOYD N. HAND* JAMES C CONNER LAWRENCE N. COOPER* LESUE a KRAMCRICM RONALD a NATALIE AMY L. BONOURANT TELEX: 9O-4I24 VERLIP-WSH DON C LEWIS' E. JOHN KRUMHOLTZ HOPEWELL H. DARNEILLE. Ill WILLIAM C. EVANS TELECOPIER: (2O2) 371-6279 LESUE M. ALDEN* MICHAEL E. SELLER MICHAEL J. ROBERTS DOUGLAS OCHS AOUER LINDA E. COLUER* RETAJ. LEWIS MARK J. ANDREWS RILEY K. TEMPLE* R. MICHAEL REGAN. JR..* ANJAU fl. CALHOUN FRITZ R. KAHN A. WAYNE LALLE. JR.* HOUSTON OFFICE GENE R. SCHLEPPKNBACH* USAJ.GETEN BERNHAROT K. WRUBLE JOHN P. CAMPBELL* MARK D. BACK MICHAEL-H. TECKUENBURG* MICHAEL J. BARTLETT* J. RICHARD HAMMCTT* THOMAS J. KELLER 69OI TEXAS COMMERCE TOWER RICHARD J. BIFFL* DOUGLAS J. COLTON JOHN J. SICILIAN JOHN A. MERRWAN 6OI MILAM SHARI a GERSTEN* JOHN H. ZENTAV LEWIS B. GARDNER* JOSEPH L. MANSON. Ill HOUSTON. TEXAS 77OO2 PETER A. GOULD* L.JOHNOSBORN FREDW. OROGULA REBECCA M J. GOULD* (713)237-9034 WILUAM E, VINCENT* ANDREA JILL GRANT JOHNS MOOT* WILUAM H. CRISPIN* TELECOPIER: (713) 237-186 JOHN a BRITTON. -

March, 2014 in THIS ISSUE President's Message Page 3 About

IN THIS ISSUE President’s Message Page 3 Articles Page 14-35 About the Cover Page 16 Letters Page 36-44 Local Reports Page 4-15 In Memoriam Page 44-46 Cruise Page 22 Calendar Page 48 Volume 17 Number 3 (Journal 654) March, 2014 —— OFFICERS —— President Emeritus: The late Captain George Howson President: Jonathan Rowbottom ................................................... 831-595-5275 ........................................ [email protected] Vice President: Cort de Peyster .................................................... 961-335-5269 .............................................. [email protected] Sec/Treas: Leon Scarbrough ......................................................... 707-938-7324 ............................................ [email protected] Membership Bob Engelman .......................................................... 954-436-3400 ........................................ [email protected] —— BOARD OF DIRECTORS —— President - Jonathan Rowbottom, Vice President - Cort de Peyster, Secretary Treasurer - Leon Scarbrough Floyd Alfson, Rich Bouska, Phyllis Cleveland, Sam Cramb, Ron Jersey, Milt Jines Walt Ramseur, Bill Smith, Cleve Spring, Larry Wright —— COMMITTEE CHAIRMEN —— Convention Sites. .......................................................... Ron Jersey ............. [email protected] RUPANEWS Manager ............................................. Cleve Spring ......... [email protected] RUPANEWS Editors................................................ Cleve Spring .................. [email protected] -

The Structuring of Neoliberalism in the US Airline Industry

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Open Access Dissertations 9-2012 Organizing Markets: The trS ucturing of Neoliberalism in the U.S. Airline Industry Dustin Robert Avent-Holt University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Avent-Holt, Dustin Robert, "Organizing Markets: The trS ucturing of Neoliberalism in the U.S. Airline Industry" (2012). Open Access Dissertations. 611. https://doi.org/10.7275/8z4d-d912 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/611 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Organizing Markets: The Structuring of Neoliberalism in the U.S. Airline Industry A Dissertation Presented by DUSTIN ROBERT AVENT-HOLT Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY September 2012 Sociology © Copyright by Dustin Avent-Holt 2012 All Rights Reserved Organizing Markets: The Structuring of Neoliberalism in the U.S. Airline Industry A Dissertation Presented by DUSTIN ROBERT AVENT-HOLT Approved as to Style and Content by: _________________________________ Donald Tomaskovic-Devey, Chair ________________________________ Joya Misra, Member ________________________________ Robert Faulkner, Member ________________________________ Michelle Budig, Member ________________________________ Michael Ash, Member ______________________________ Donald Tomaskovic-Devey, Chair Department of Sociology ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS What seems like to many years ago I started an unpredictable journey into academia because I wanted to understand the world around me and in some way transform that world. -

Reduction of Labor Costs in the Airline Industry John V

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 49 | Issue 3 Article 2 1984 Coping with Deregulation: Reduction of Labor Costs in the Airline Industry John V. Jansonius Kenneth E. Broughton Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation John V. Jansonius et al., Coping with Deregulation: Reduction of Labor Costs in the Airline Industry, 49 J. Air L. & Com. 501 (1984) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol49/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. COPING WITH DEREGULATION: REDUCTION OF LABOR COSTS IN THE AIRLINE INDUSTRY JOHN V. JANSONIUS* and KENNETH E. BROUGHTON** W ITH PASSAGE of the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978,' Congress radically altered the manner in which the nation's air carriers conduct business. An industry accus- tomed to extensive government regulation and oversight was suddenly exposed to the economic and market freedoms en- joyed by most American industries.' Not surprisingly, the few years that have elapsed since deregulation have been the * B.A., 1977, Drake University; J.D., 1980, Southern Methodist University. Mr. Jansonius is an associate with the Dallas law firm of Haynes and Boone. ** B.A., 1978; J.D., 1981, Baylor University. Mr. Broughton is also an associate with Haynes and Boone. I Pub. L. No. 95-504, 92 Stat. 1705 (1978) (codified at 49 U.S.C. -

B-2 Historic Building Documentation Continental Airlines General Office Building

B-2 Historic Building Documentation Continental Airlines General Office Building Los Angeles International Airport LAX Secured Area Access Post Project July 2017 Draft EIR Los Angeles International Airport LAX Secured Area Access Post Project July 2017 Draft EIR Continental Airlines General Office Building PAGE 1 HISTORIC BUILDING DOCUMENTATION CONTINENTAL AIRLINES GENERAL OFFICE BUILDING January 2017 Location: Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) is located in the southwest portion of Los Angeles County, California. It is bounded on the north by the neighborhoods of Westchester and Playa del Rey; on the south by Imperial Highway, the City of El Segundo, and the community of Del Aire (unincorporated Los Angeles County); on the east by Aviation Boulevard, the City of Inglewood, and the community of Lennox (unincorporated Los Angeles County); and on the west by Vista del Mar Boulevard. The Continental Airlines General Office Building is located on the south side of World Way West at 7270 World Way West, due west of the main LAX terminals, in the airport support facilities area.1 Present Owner: Los Angeles World Airports Present Use: Vacant Significance: The Continental Airlines General Office Building (“General Office Building”) is significant under National Register Criterion A and California Register Criterion 1 as an aviation property associated with the rapid development of commercial aviation in the years after World War II, which had prompted advances in aircraft design and technology. It is also significant under National Register Criterion C and California Register Criterion 3 as an aviation property that embodies the distinct characteristics of Mid-century Modern architecture, which reflects the period during which Los Angeles International Airport was developed. -

Airline Competition Hearings Committee On

S. HRG. 105±936 AIRLINE COMPETITION HEARINGS BEFORE A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTH CONGRESS FIRST AND SECOND SESSIONS SPECIAL HEARINGS Printed for the use of the Committee on Appropriations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 53±117 cc WASHINGTON : 1999 For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, Washington, DC 20402 ISBN 0±16±058362±4 COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS TED STEVENS, Alaska, Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont SLADE GORTON, Washington DALE BUMPERS, Arkansas MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey CONRAD BURNS, Montana TOM HARKIN, Iowa RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire HARRY REID, Nevada ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah HERB KOHL, Wisconsin BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado PATTY MURRAY, Washington LARRY CRAIG, Idaho BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota LAUCH FAIRCLOTH, North Carolina BARBARA BOXER, California KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas STEVEN J. CORTESE, Staff Director LISA SUTHERLAND, Deputy Staff Director JAMES H. ENGLISH, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON TRANSPORTATION AND RELATED AGENCIES RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama, Chairman PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland SLADE GORTON, Washington HARRY REID, Nevada ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah HERB KOHL, Wisconsin LAUCH FAIRCLOTH, North Carolina PATTY MURRAY, Washington TED STEVENS, Alaska ex officio Professional Staff WALLY BURNETT ANNE M.