Military Police

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mini-SITREP XXXIV

mini-SITREP XXXIV Eldoret Agricultural Show - February 1959. HM The Queen Mother inspecting Guard of Honour provided by ‘C’ Company commanded by Maj Jock Rutherford [KR5659]. Carrying the Queen Mother’s Colour Lt Don Rooken- Smith [KR5836]. Third from right wearing the Colorado Beetle, Richard Pembridge [KR6381] Edited and Printed by the Kenya Regiment Association (KwaZulu-Natal) – June 2009 1 KRA/EAST AFRICA SCHOOLS DIARY OF EVENTS: 2009 KRA (Australia) Sunshine Coast Curry Lunch, Oxley Golf Club Sun 16th Aug (TBC) Contact: Giles Shaw. 07-3800 6619 <[email protected]> Sydney’s Gold Coast. Ted Downer. 02-9769 1236 <[email protected]> Sat 28th Nov (TBC) East Africa Schools - Australia 10th Annual Picnic. Lane Cove River National Park, Sydney Sun 25th Oct Contact: Dave Lichtenstein 01-9427 1220 <[email protected]> KRAEA Remembrance Sunday and Curry Lunch at Nairobi Clubhouse Sun 8th Nov Contact: Dennis Leete <[email protected]> KRAENA - England Curry Lunch: St Cross Cricket Ground, Winchester Thu 2nd Jul AGM and Lunch: The Rifles London Club, Davies St Wed 18th Nov Contact: John Davis. 01628-486832 <[email protected]> SOUTH AFRICA Cape Town: KRA Lunch at Mowbray Golf Course. 12h30 for 13h00 Thu 18th Jun Contact: Jock Boyd. Tel: 021-794 6823 <[email protected]> Johannesburg: KRA Lunch Sun 25th Oct Contact: Keith Elliot. Tel: 011-802 6054 <[email protected]> KwaZulu-Natal: KRA Saturday quarterly lunches: Hilton Hotel - 13 Jun, 12 Sep and 12 Dec Contact: Anne/Pete Smith. Tel: 033-330 7614 <[email protected]> or Jenny/Bruce Rooken-Smith. Tel: 033-330 4012 <[email protected]> East Africa Schools’ Lunch. -

FOR ENGLAND August 2018

St GEORGE FOR ENGLAND DecemberAugust 20182017 In this edition The Murder of the Tsar The Royal Wedding Cenotaph Cadets Parade at Westminster Abbey The Importance of Archives THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF St. GEORGE – The Premier Patriotic Society of England Founded in 1894. Incorporated by Royal Charter. Patron: Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II £3.50 Proud to be working with The Royal Society of St. George as the of cial printer of "St. George for England". One of the largest printing groups in the UK with six production sites. We offer the following to an extensive portfolio of clients and market sectors: • Our services: Printing, Finishing, Collation, Ful lment, Pick & Pack, Mailing. • Our products: Magazines, Brochures, Lea ets, Catalogues and Training Manuals. • Our commitment: ISO 14001, 18001, 9001, FSC & PEFC Accreditation. wyndehamgroup Call Trevor Stevens on 07917 576478 $$%# #%)( $#$#!#$%( '#$%) # &%#% &#$!&%)%#% % !# %!#$#'%&$&#$% % #)# ( #% $&#%%%$% ##)# %&$% '% &%&# #% $($% %# &%% ) &! ! #$ $ %# & &%% &# &#)%'%$& #$(%%(#)&#$'!#%&# %%% % #)# &%#!# %$ # #$#) &$ $ #'%% !$$ %# & &# ## $#'$(# # &"&%)*$ &#$ # %%!#$% &$ ## (#$ #) &! ! '#)##'$'*$)#!&$'%% $% '#%) % '%$& &#$% #(##$##$$)"&%)$!#$# # %#%$ # $% # # #% !$ %% #'$% # +0 +))%)$ -0$,)'*(0&$'$- 0".+(- + "$,- + $(("&()'*(0) ( "$,- + #+$-0) "$,- + !!$ (+ ,,!)+)++ ,*)( ( # -.$))*0#)&+'0+)/ )+$(" -# $(" Contents Vol 16. No. 2 – August 2018 Front Cover: Tower Bridge, London 40 The Royal Wedding 42 Cenotaph Cadets Parade and Service at Westminster St George -

NRA Police Pistol Combat Rule Book

NRA Police Pistol Combat Rule Book 2020 Amendments On January 4, 2020, the NRA Board of Directors approved the Law Enforcement Assistance Committees request to amend the NRA Police Pistol Combat Rule Book. These amendments have been incorporated into this web based printable PPC Rule Book. The 2020 amendments are as follows: Amendment 1 is in response to competitor requests concerning team matches at the National Police Shooting Championships. Current rules require that team match membership be comprised of members from the same law enforcement agency. A large percentage of competitors who attend the Championships are solo shooters, meaning they are the only member of their agency in attendance. The amendment allows the Championships to offer a stand-alone NPSC State Team Match so that solo competitors from the same state can compete as a team. The Match will be fired at the same time as regular team matches so no additional range time is needed, and State Team scores will only be used to determine placement in the State Team Match. NPSC State Team Match scores will not be used in determining National Team Champions, however they are eligible for National Records for NPSC State Team Matches. The amendment allows solo shooters the opportunity to fire additional sanctioned matches at the Championships and enhance team participation. 2.9 National Police Shooting Championships State Team Matches: The Tournament Director of the National Police Shooting Championships may offer two officer Open Class and Duty Gun Division NPSC Team Matches where team membership is comprised of competitors from the same state. For a team to be considered a NPSC State Team; 1. -

Welsh Guards Magazine 2020

105 years ~ 1915 - 2020 WELSH GUARDS REGIMENTAL MAGAZINE 2020 WELSH GUARDS WELSH GUARDS REGIMENTAL MAGAZINE 2020 MAGAZINE REGIMENTAL Cymru Am Byth Welsh Guards Magazine 2020_COVER_v3.indd 1 24/11/2020 14:03 Back Cover: Lance Sergeant Prothero from 1st Battalion Welsh Guards, carrying out a COVID-19 test, at testing site in Chessington, Kingston-upon-Thames. 1 2 3 4 5 6 8 1. Gdsm Wilkinson being 7 promoted to LCpl. 2. Gdsm Griffiths being promoted to LCpl. 3. LSgt Sanderson RLC being awarded the Long Service and Good Conduct Medal. 4. Sgt Edwards being promoted to CSgt. 5. Gdsm Davies being promoted to LCpl. 6. Gdsm Evans 16 being awarded the Long Service and Good Conduct Medal. 7. LSgt Bilkey, 3 Coy Recce, being promoted to Sgt 8. LSgt Jones, 3 Coy Snipers, being promoted to Sgt 9 9. Sgt Simons being awarded the Long Service and Good Conduct Medal. Front Cover: 1st Battalion Welsh Guards Birthday Tribute to 10. LSgt Lucas, 2 Coy being Her Majesty The Queen, Windsor Castle, Saturday 13th June 2020 10 promoted to Sgt Welsh Guards Magazine 2020_COVER_v3.indd 2 24/11/2020 14:04 WELSH GUARDS REGIMENTAL MAGAZINE 2020 COLONEL-IN-CHIEF Her Majesty The Queen COLONEL OF THE REGIMENT His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales KG KT GCB OM AK QSO PC ADC REGIMENTAL LIEUTENANT COLONEL Major General R J Æ Stanford MBE REGIMENTAL ADJUTANT Colonel T C S Bonas BA ASSISTANT REGIMENTAL ADJUTANT Major M E Browne BEM REGIMENTAL VETERANS OFFICER Jiffy Myers MBE ★ REGIMENTAL HEADQUARTERS Wellington Barracks, Birdcage Walk, London SW1E 6HQ Contact Regimental Headquarters by Email: [email protected] View the Regimental Website at: www.army.mod.uk/welshguards View the Welsh Guards Charity Website at: www.welshguardscharity.co.uk Contact the Regimental Veterans Officer at: [email protected] ★ AFFILIATIONS HMS Prince of Wales 5th Battalion The Royal Australian Regiment Régiment de marche du Tchad ©Crown Copyright: This publication contains official information. -

NATO ARMIES and THEIR TRADITIONS the Carabinieri Corps and the International Environment by LTC (CC) Massimo IZZO - LTC (CC) Tullio MOTT - WO1 (CC) Dante MARION

NATO ARMIES AND THEIR TRADITIONS The Carabinieri Corps and the International Environment by LTC (CC) Massimo IZZO - LTC (CC) Tullio MOTT - WO1 (CC) Dante MARION The Ancient Corps of the Royal Carabinieri was instituted in Turin by the King of Sardinia, Vittorio Emanuele 1st by Royal Warranty on 13th of July 1814. The Carabinieri Force was Issued with a distinctive uniform in dark blue with silver braid around the collar and cuffs, edges trimmed in scarlet and epaulets in silver, with white fringes for the mounted division and light blue for infantry. The characteristic hat with two points was popularly known as the “Lucerna”. A version of this uniform is still used today for important ceremonies. Since its foundation Carabinieri had both Military and Police functions. In addition they were the King Guards in charge for security and honour escorts, in 1868 this task has been given to a selected Regiment of Carabinieri (height not less than 1.92 mt.) called Corazzieri and since 1946 this task is performed in favour of the President of the Italian Republic. The Carabinieri Force took part to all Italian Military history events starting from the three independence wars (1848) passing through the Crimean and Eritrean Campaigns up to the First and Second World Wars, between these was also involved in the East African military Operation and many other Military Operations. During many of these military operations and other recorded episodes and bravery acts, several honour medals were awarded to the flag. The participation in Military Operations abroad (some of them other than war) began with the first Carabinieri Deployment to Crimea and to the Red Sea and continued with the presence of the Force in Crete, Macedonia, Greece, Anatolia, Albania, Palestine, these operations, where the basis leading to the acquirement of an international dimension of the Force and in some of them Carabinieri supported the built up of the local Police Forces. -

The German Military and Hitler

RESOURCES ON THE GERMAN MILITARY AND THE HOLOCAUST The German Military and Hitler Adolf Hitler addresses a rally of the Nazi paramilitary formation, the SA (Sturmabteilung), in 1933. By 1934, the SA had grown to nearly four million members, significantly outnumbering the 100,000 man professional army. US Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of William O. McWorkman The military played an important role in Germany. It was closely identified with the essence of the nation and operated largely independent of civilian control or politics. With the 1919 Treaty of Versailles after World War I, the victorious powers attempted to undercut the basis for German militarism by imposing restrictions on the German armed forces, including limiting the army to 100,000 men, curtailing the navy, eliminating the air force, and abolishing the military training academies and the General Staff (the elite German military planning institution). On February 3, 1933, four days after being appointed chancellor, Adolf Hitler met with top military leaders to talk candidly about his plans to establish a dictatorship, rebuild the military, reclaim lost territories, and wage war. Although they shared many policy goals (including the cancellation of the Treaty of Versailles, the continued >> RESOURCES ON THE GERMAN MILITARY AND THE HOLOCAUST German Military Leadership and Hitler (continued) expansion of the German armed forces, and the destruction of the perceived communist threat both at home and abroad), many among the military leadership did not fully trust Hitler because of his radicalism and populism. In the following years, however, Hitler gradually established full authority over the military. For example, the 1934 purge of the Nazi Party paramilitary formation, the SA (Sturmabteilung), helped solidify the military’s position in the Third Reich and win the support of its leaders. -

The Portuguese Colonial War: Why the Military Overthrew Its Government

The Portuguese Colonial War: Why the Military Overthrew its Government Samuel Gaspar Rodrigues Senior Honors History Thesis Professor Temma Kaplan April 20, 2012 Rodrigues 2 Table of Contents Introduction ..........................................................................................................................3 Before the War .....................................................................................................................9 The War .............................................................................................................................19 The April Captains .............................................................................................................33 Remembering the Past .......................................................................................................44 The Legacy of Colonial Portugal .......................................................................................53 Bibliography ......................................................................................................................60 Rodrigues 3 Introduction When the Portuguese people elected António Oliveira de Salazar to the office of Prime Minister in 1932, they believed they were electing the right man for the job. He appealed to the masses. He was a far-right conservative Christian, but he was less radical than the Portuguese Fascist Party of the time. His campaign speeches appeased the syndicalists as well as the wealthy landowners in Portugal. However, he never was -

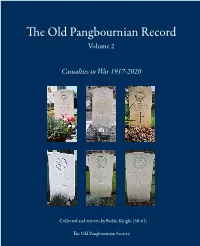

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society The Old angbournianP Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society First published in the UK 2020 The Old Pangbournian Society Copyright © 2020 The moral right of the Old Pangbournian Society to be identified as the compiler of this work is asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, “Beloved by many. stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any Death hides but it does not divide.” * means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the Old Pangbournian Society in writing. All photographs are from personal collections or publicly-available free sources. Back Cover: © Julie Halford – Keeper of Roll of Honour Fleet Air Arm, RNAS Yeovilton ISBN 978-095-6877-031 Papers used in this book are natural, renewable and recyclable products sourced from well-managed forests. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro, designed and produced *from a headstone dedication to R.E.F. Howard (30-33) by NP Design & Print Ltd, Wallingford, U.K. Foreword In a global and total war such as 1939-45, one in Both were extremely impressive leaders, soldiers which our national survival was at stake, sacrifice and human beings. became commonplace, almost routine. Today, notwithstanding Covid-19, the scale of losses For anyone associated with Pangbourne, this endured in the World Wars of the 20th century is continued appetite and affinity for service is no almost incomprehensible. -

MILITARY POLICE, an Official U.S

USAMPS / MANSCEN This medium is approved for the official dissemination 573-XXX-XXXX / DSN 676-XXXX of material designed to keep individuals within the Army COMMANDANT knowledgeable of current and emerging developments within BG Stephen J. Curry .................................................... 563-8019 their areas of expertise for the purpose of enhancing their <[email protected]> professional development. ACTING ASSISTANT COMMANDANT By Order of the Secretary of the Army: COL Charles E. Bruce .................................................. 563-8017 PETER J. SCHOOMAKER <[email protected]> General, United States Army COMMAND SERGEANT MAJOR Chief of Staff CSM James F. Barrett .................................................. 563-8018 Official: <[email protected]> DEPUTY ASSISTANT COMMANDANT—USAR COL Charles E. Bruce .................................................. 563-8082 JOEL B. HUDSON <[email protected]> Administrative Assistant to the DEPUTY ASSISTANT COMMANDANT—ARNG Secretary of the Army LTC Starrleen J. Heinen .................................. 596-0131, 38103 02313130330807 <[email protected]> DIRECTOR of TRAINING DEVELOPMENT MILITARY POLICE, an official U.S. Army professional COL Edward J. Sannwaldt, Jr........................................ 563-4111 bulletin for the Military Police Corps Regiment, contains infor- <[email protected]> mation about military police functions in maneuver and DIRECTORATE of COMBAT DEVELOPMENTS mobility operations, area security operations, internment/ MP DIVISION CHIEF -

MILITARY INTELLIGENCE PB 34-09-2 Volume 35 Number 2 April - June 2009

MIPB April - June 2009 PB 34-O9-2 Operations in OEF Afghanistan FROM THE EDITOR In this issue, three articles offer perspectives on operations in Afghanistan. Captain Nenchek dis- cusses the philosophy of the evolving insurgent “syndicates,” who are working together to resist the changes and ideas the Coalition Forces bring to Afghanistan. Captain Beall relates his experiences in employing Human Intelligence Collection Teams at the company level in both Iraq and Afghanistan. Lieutenant Colonel Lawson provides a look into the balancing act U.S. Army chaplains as non-com- batants in Afghanistan are involved in with regards to Information Operations. Colonel Reyes discusses his experiences as the MNF-I C2 CIOC Chief, detailing the problems and solutions to streamlining the intelligence effort. First Lieutenant Winwood relates her experiences in integrating intelligence support into psychological operations. From a doctrinal standpoint, Lieutenant Colonels McDonough and Conway review the evolution of priority intelligence requirements from a combined operations/intelligence view. Mr. Jack Kem dis- cusses the constructs of assessment during operations–measures of effectiveness and measures of per- formance, common discussion threads in several articles in this issue. George Van Otten sheds light on a little known issue on our southern border, that of the illegal im- migration and smuggling activities which use the Tohono O’odham Reservation as a corridor and offers some solutions for combined agency involvement and training to stem the flow. Included in this issue is nomination information for the CSM Doug Russell Award as well as a biogra- phy of the 2009 winner. Our website is at https://icon.army.mil/ If your unit or agency would like to receive MIPB at no cost, please email [email protected] and include a physical address and quantity desired or call the Editor at 520.5358.0956/DSN 879.0956. -

CADETS in PORTUGUESE MILITARY ACADEMIES a Sociological Portrait

CADETS IN PORTUGUESE MILITARY ACADEMIES A sociological portrait Helena Carreiras Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL), Centro de Investigação e Estudos de Sociologia (Cies_Iscte), Lisboa, Portugal Fernando Bessa Military University Institute, Centre for Research in Security and Defence (CISD), Lisboa, Portugal Patrícia Ávila Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL), Centro de Investigação e Estudos de Sociologia (Cies_Iscte), Lisboa, Portugal Luís Malheiro Military University Institute, Centre for Research in Security and Defence (CISD), Lisboa, Portugal Abstract The aim of this article is to revisit the question of the social origins of the armed forces officer corps, using data drawn from a survey to all cadets following military training at the three Portuguese service academies in 2016. It puts forward the question of whether the sociological characteristics of the future military elite reveal a pattern of convergence with society or depart from it, in terms of geographical origins, gender and social origins. The article offers a sociological portrait of the cadets and compares it with previous studies, identifying trends of change and continuity. The results show that there is a diversified and convergent recruitment pattern: cadets are coming from a greater variety of regions in the country than in the past; there is a still an asymmetric but improving gender balance; self-recruitment patterns are rather stable, and there is a segmented social origin pointing to the dominance of the more qualified and affluent social classes. In the conclusion questions are raised regarding future civil-military convergence patterns as well as possible growing differences between ranks. Keywords: military cadets, officer corps, social origins, civil-military relations. -

ATP 3-39.10. Police Operations

ATP 3-39.10 POLICE OPERATIONS AUGUST 2021 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for Public Release; distribution is unlimited. This publication supersedes ATP 3-39.10, 26 January 2015. Headquarters, Department of the Army This publication is available at the Army Publishing Directorate site (https:// armypubs.army.mil), and the Central Army Registry site (https://atiam.train.army.mil/catalog/dashboard). *ATP 3-39.10 Army Techniques Publication Headquarters No. 3-39.10 Department of the Army Washington, D.C., 24 August 2021 Police Operations Contents Page PREFACE..................................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ vii Chapter 1 POLICE OPERATIONS SUPPORT TO ARMY OPERATIONS ............................... 1-1 The Police Operations Discipline .............................................................................. 1-1 Principles of Police Operations ................................................................................. 1-4 Rule of Law ................................................................................................................ 1-6 Command and Control of Army Law Enforcement .................................................... 1-7 Operational Environment ........................................................................................... 1-9 Unified Action .........................................................................................................