Amur Chokecherry Prunus Maackii Rupr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prunus Maackii

Woody Plants Database [http://woodyplants.cals.cornell.edu] Species: Prunus maackii Amur Chokecherry, Manchurian Chokecherry Cultivar Information * See specific cultivar notes on next page. Ornamental Characteristics Size: Tree > 30 feet Height: 35 to 45' tall, 25 to 35' wide Leaves: Deciduous Shape: Young trees are pyramidal, rounded and dense at maturity Ornamental Other: full sun Environmental Characteristics Light: Full sun Hardy To Zone: 3a Soil Ph: Can tolerate acid to alkaline soil (pH 5.0 to 8.0) Environmental Other: full sun Insect Disease aphids, scale, borers Bare Root Transplanting Any Other Native to Manchuria and Korea Moisture Tolerance 1 Woody Plants Database [http://woodyplants.cals.cornell.edu] Occasionally saturated Consistently moist, Occasional periods of Prolonged periods of or very wet soil well-drained soil dry soil dry soil 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 2 Woody Plants Database [http://woodyplants.cals.cornell.edu] Cultivars for Prunus maackii Showing 1-3 of 3 items. Cultivar Name Notes Amber Beauty 'Amber Beauty'- Forms a uniform tree with slightly ascending branches Goldspur 'Goldspur' (a.k.a.'Jefspur') - dwarf, multi-stemmed, narrowly upright and columnar growth habit; resistant to black knot; grows to 15' tall x 10' wide; Goldrush 'Goldrush' (a.k.a. 'Jefree') - upright growth habit; resistant to black rot; improved resistance to frost cracking; grows to 25' tall x 16' wide 3 Woody Plants Database [http://woodyplants.cals.cornell.edu] Photos Prunus maackii - Bark Prunus maackii - Bark 4 Woody Plants Database [http://woodyplants.cals.cornell.edu] Prunus maackii - Bark Prunus maackii - Leaves 5 Woody Plants Database [http://woodyplants.cals.cornell.edu] Prunus maackii - Habit Prunus maackii - Leaves 6 Woody Plants Database [http://woodyplants.cals.cornell.edu] Prunus maackii - Habit Prunus maackii - Habit 7 Woody Plants Database [http://woodyplants.cals.cornell.edu] Prunus maackii - Habit 8. -

Nursery Price List

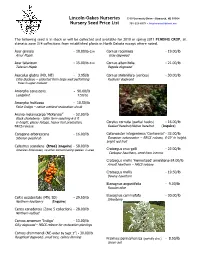

Lincoln-Oakes Nurseries 3310 University Drive • Bismarck, ND 58504 Nursery Seed Price List 701-223-8575 • [email protected] The following seed is in stock or will be collected and available for 2010 or spring 2011 PENDING CROP, all climatic zone 3/4 collections from established plants in North Dakota except where noted. Acer ginnala - 18.00/lb d.w Cornus racemosa - 19.00/lb Amur Maple Gray dogwood Acer tataricum - 15.00/lb d.w Cornus alternifolia - 21.00/lb Tatarian Maple Pagoda dogwood Aesculus glabra (ND, NE) - 3.95/lb Cornus stolonifera (sericea) - 30.00/lb Ohio Buckeye – collected from large well performing Redosier dogwood Trees in upper midwest Amorpha canescens - 90.00/lb Leadplant 7.50/oz Amorpha fruiticosa - 10.50/lb False Indigo – native wetland restoration shrub Aronia melanocarpa ‘McKenzie” - 52.00/lb Black chokeberry - taller form reaching 6-8 ft in height, glossy foliage, heavy fruit production, Corylus cornuta (partial husks) - 16.00/lb NRCS release Beaked hazelnut/Native hazelnut (Inquire) Caragana arborescens - 16.00/lb Cotoneaster integerrimus ‘Centennial’ - 32.00/lb Siberian peashrub European cotoneaster – NRCS release, 6-10’ in height, bright red fruit Celastrus scandens (true) (Inquire) - 58.00/lb American bittersweet, no other contaminating species in area Crataegus crus-galli - 22.00/lb Cockspur hawthorn, seed from inermis Crataegus mollis ‘Homestead’ arnoldiana-24.00/lb Arnold hawthorn – NRCS release Crataegus mollis - 19.50/lb Downy hawthorn Elaeagnus angustifolia - 9.00/lb Russian olive Elaeagnus commutata -

Phylogenetic Inferences in Prunus (Rosaceae) Using Chloroplast Ndhf and Nuclear Ribosomal ITS Sequences 1Jun WEN* 2Scott T

Journal of Systematics and Evolution 46 (3): 322–332 (2008) doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1002.2008.08050 (formerly Acta Phytotaxonomica Sinica) http://www.plantsystematics.com Phylogenetic inferences in Prunus (Rosaceae) using chloroplast ndhF and nuclear ribosomal ITS sequences 1Jun WEN* 2Scott T. BERGGREN 3Chung-Hee LEE 4Stefanie ICKERT-BOND 5Ting-Shuang YI 6Ki-Oug YOO 7Lei XIE 8Joey SHAW 9Dan POTTER 1(Department of Botany, National Museum of Natural History, MRC 166, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20013-7012, USA) 2(Department of Biology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523, USA) 3(Korean National Arboretum, 51-7 Jikdongni Soheur-eup Pocheon-si Gyeonggi-do, 487-821, Korea) 4(UA Museum of the North and Department of Biology and Wildlife, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK 99775-6960, USA) 5(Key Laboratory of Plant Biodiversity and Biogeography, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming 650204, China) 6(Division of Life Sciences, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon 200-701, Korea) 7(State Key Laboratory of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100093, China) 8(Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Tennessee, Chattanooga, TN 37403-2598, USA) 9(Department of Plant Sciences, MS 2, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA) Abstract Sequences of the chloroplast ndhF gene and the nuclear ribosomal ITS regions are employed to recon- struct the phylogeny of Prunus (Rosaceae), and evaluate the classification schemes of this genus. The two data sets are congruent in that the genera Prunus s.l. and Maddenia form a monophyletic group, with Maddenia nested within Prunus. -

North Dakota Tree Selector Amur Chokecherry

NORTH DAKOTA STATE UNIVERSITY North Dakota Tree Selector Amur Chokecherry General Scientific Name: Prunus Description maackii Prunus maackii, commonly called Manchurian cherry, Amur cherry Family: Roseaceae (Rose) or Amur chokecherry, is a graceful ornamental flowering cherry tree Hardiness: Zone 3 that typically grows 20-30’ tall with a dense, broad-rounded crown. It is native to Manchuria, Siberia and Korea. It is perhaps most Leaves: Deciduous noted for its attractive, exfoliating golden brown to russet Plant type: Tree bark. Fragrant flowers appear in late spring and are followed by black fruits. Growth Preferences Rate: N/A Light: Full sun Mature height: 25-45’ Water: Medium Longevity: Short Soil: Average well drained soils Power Line: No Comments Ornamental An excellent tree for lawns or as a street tree. It can be used Flowers: White to cream individually or in a grouping of multiple species. Amur chokecherry fruits are excellent for wildlife and birds while the tree serves as a Fruit: Black cherry-like nesting site for songbirds. It is a short lived tree with an expected Fall Color: Yellow lifespan of 25-30 years. Credits: Tree Selector Website, https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/trees/handbook/th-3-13.pdf www.ag.ndsu.edu/tree-selector NDSU does not discriminate in its programs and activities on the basis of age, color, gender expression/identity, genetic inf ormation, marital status, national origin, participation in lawful off-campus activity, physical or mental disability, pregnancy, public assistance status, race, religion, sex, sexual orientation, spousal relationship to curr ent employee, or vete ran status, as applicable. -

Seed Stratification Treatments for Two Hardy Cherry Species

Tree Planter's Notes, Vol. 37, No. 3 (1986) Summer 1986/35 Seed Stratification Treatments for Two Hardy Cherry Species Greg Morgenson Assistant nurseryman, Lincoln-Oakes Nurseries, Bismark, ND The seed-propagated selection Information regarding seed Seed of Mongolian cherry (Prunus 'Scarlet' Mongolian cherry (figs. 1 propagation of these two species is fruticosa Pallas) germinated best after and 2) has recently been released limited. Initial late fall nursery seedings 30 days of warm plus 90 days of cold by the USDA Soil Conservation resulted in minimal germination the stratification. Amur chokecherry Service for conservation purposes in following spring but in satisfactory (Prunus maackii Rupr.) was best after the Northern Plains (4). germination the second spring after 30 days of warm plus 60 days of cold Prunus maackii is placed in the planting. stratification. Longer stratification subgenus Padus. It ranges from Seed of Prunus species require a periods resulted in germination during Manchuria to Korea and is rated as period of after-ripening to aid in storage. Tree Planters' Notes zone II in hardiness (3). It is a overcoming embryo dormancy (2). 37(3):3538; 1986. nonsuckering tree that grows to 15 Several species require a warm meters in height. Its leaves are dull stratification period followed by cold green. The dark purple fruits are borne stratification. It was believed that P. in racemes and are utilized by wildlife. fruticosa and P. maackii might benefit The genus Prunus contains many Amur chokecherry is often planted as from this. Researchers at the Morden native and introduced species that are an ornamental because of its Manitoba Experimental Farm found that hardy in the Northern Plains and are copper-colored, flaking bark, but it germination of P. -

An Albertan Plant Journal

An Albertan Plant Journal By Traci Berg Disclaimer *My plant journal lists over 70 species that are commonly used in landscaping and gardening in Calgary, Alberta, which is listed by Natural Resources Canada as a 4a zone as of 2010. These plants were documented over several plant walks at the University of Calgary and at Eagle Lake Nurseries in September and October of 2018. My plant journal is by no means exclusive; there are plenty of native and non-native species that are thriving in Southern Alberta, and are not listed here. This journal is simply meant to serve as both a personal study tool and reference guide for selecting plants for landscaping. * All sketches and imagery in this plant journal are © Tessellate: Craft and Cultivations by Traci Berg and may not be used without the artist’s permission. Thank you, enjoy! Table of Contents Adoxaceae Family 1 Viburnum lantana “Wayfaring Tree” 1 Viburnum trilobum “High Bush Cranberry” 1 Anacardiaceae Family 2 Rhus typhina x ‘Bailtiger’ “Tiger Eyes Sumac” 2 Asparagaceae Family 3 Polygonatum odoratum “Solomon’s Seal” 3 Hosta x ‘June’ “June Hosta” 3 Betulaceae Family 4 Betula papyrifera ‘Clump’ “Clumping White/Paper Birch” 4 Betula pendula “Weeping Birch” 4 Berberidaceae Family 5 Berberis thunbergii “Japanese Barberry” 5 Caprifoliaceae Family 5 Symphoricarpos albus “Snowberry” 5 Cornaceae Family 6 Cornus alba “Ivory Halo/Silver Leaf Dogwood” 6 Cornus stolonifera/sericea “Red Osier Dogwood” 6 Cupressaceae Family 7 Juniperus communis “Common Juniper” 7 Juniperus horizontalis “Creeping/Horizontal Juniper” 7 Juniperus sabina “Savin Juniper” 8 Thuja occidentalis “White Cedar” 8 Elaegnaceae Family 9 Shepherdia canadensis “Russet Buffaloberry” 9 Elaeagnus commutata “Wolf Willow/Silverberry” 9 Fabaceae Family 10 Caragana arborscens “Weeping Caragana” 10 Caragana pygmea “Pygmy Caragana” 10 Fagaceae Family 11 Quercus macrocarpa “Bur Oak” 11 Grossulariaceae Family 12 Ribes alpinum “Alpine Currant” 12 Hydrangeaceae Family 12 Hydrangea paniculata ‘Grandiflora’ “Pee Gee Hydrangea” 13 Philadelphus sp. -

Interspecific Hybridizations in Ornamental Flowering Cherries

J. AMER.SOC.HORT.SCI. 138(3):198–204. 2013. Interspecific Hybridizations in Ornamental Flowering Cherries Validated by Simple Sequence Repeat Analysis Margaret Pooler1 and Hongmei Ma USDA-ARS, U.S. National Arboretum, 10300 Baltimore Avenue, Building 010A, Beltsville, MD 20705 ADDITIONAL INDEX WORDS. simple sequence repeat, molecular markers, plant breeding, Prunus ABSTRACT. Flowering cherries belong to the genus Prunus, consisting primarily of species native to Asia. Despite the popularity of ornamental cherry trees in the landscape, most ornamental Prunus planted in the United States are derived from a limited genetic base of Japanese flowering cherry taxa. Controlled crosses among flowering cherry species carried out over the past 30 years at the U.S. National Arboretum have resulted in the creation of interspecific hybrids among many of these diverse taxa. We used simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers to verify 73 of 84 putative hybrids created from 43 crosses representing 20 parental taxa. All verified hybrids were within the same section (Cerasus or Laurocerasus in the subgenus Cerasus) with no verified hybrids between sections. Ornamental flowering cherry trees are popular plants for pollen parent bloomed before the seed parent, anthers were street, commercial, and residential landscapes. Grown primar- collected from the pollen donor just before flower opening and ily for their spring bloom, flowering cherries have been in the allowed to dehisce in gelatin capsules which were stored in United States since the mid-1850s (Faust and Suranyi, 1997), paper coin envelopes in the refrigerator before use. In most and they gained in popularity after the historic Tidal Basin cases, the seed parent was emasculated before pollination. -

Screening Ornamental Cherry (Prunus) Taxa for Resistance to Infection by Blumeriella Jaapii

HORTSCIENCE 53(2):200–203. 2018. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI12563-17 and likely most effective method for long- term disease management. Disease-resistant taxa have been found for use in sour and Screening Ornamental Cherry sweet cherry breeding programs (Stegmeir et al., 2014; Wharton et al., 2003), and (Prunus) Taxa for Resistance to detached leaf assays have been developed (Wharton et al., 2003). A field screening of Infection by Blumeriella jaapii six popular ornamental cultivars revealed differential resistance in those taxa as well Yonghong Guo (Joshua et al., 2017). The objectives of the Floral and Nursery Plants Research Unit, U.S. National Arboretum, U.S. present study were 2-fold: 1) to screen Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, 10300 Baltimore a large and diverse base of ornamental flowering cherry germplasm to identify the Avenue, Beltsville, MD 20705 most resistant taxa for use in landscape Matthew Kramer plantings and in our breeding program, and 2) to verify that our detached leaf assay Statistics Group, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research for this fungus was effective for flowering Service, 10300 Baltimore Avenue, Beltsville, MD 20705 cherry taxa, where whole tree assays are Margaret Pooler1 often impractical. Floral and Nursery Plants Research Unit, U.S. National Arboretum, U.S. Materials and Methods Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, 10300 Baltimore Avenue, Beltsville, MD 20705 Plant materials. Sixty-nine diverse acces- sions of ornamental flowering cherries were Additional index words. breeding, flowering cherry, germplasm evaluation, cherry leaf spot selected for testing. These plants were mature Abstract. Ornamental flowering cherry trees are important landscape plants in the trees representing multiple accessions of United States but are susceptible to several serious pests and disease problems. -

Plant Inventory No. 212 Is the Official Listing of Plant Materials Accepted Into the U.S

United States Department of Agriculture Plant Inventory Agricultural Research Service No. 212 Plant Materials Introduced in 2003 (Nos. 632417 - 634360) Foreword Plant Inventory No. 212 is the official listing of plant materials accepted into the U.S. National Plant Germplasm System (NPGS) between January 1 and December 31, 2003 and includes PI 632417 to PI 634360. The NPGS is managed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Agricultural Research Service (ARS). The information on each accession is essentially the information provided with the plant material when it was obtained by the NPGS. The information on an accession in the NPGS database may change as additional knowledge is obtained. The Germplasm Resources Information Network (http://www.ars-grin.gov/npgs/index.html) is the database for the NPGS and should be consulted for the current accession and evaluation information and to request germplasm. While the USDA/ARS attempts to maintain accurate information on all NPGS accessions, it is not responsible for the quality of the information it has been provided. For questions about this volume, contact the USDA/ARS/National Germplasm Resources Laboratory/Database Management Unit: [email protected] The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in its programs on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs and marital or familial status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact the USDA Office of Communications at (202) 720-2791. To file a complaint, write the Secretary of Agriculture, U.S. -

Approved Plant List

LEGEND Preferred Species Do not over water Abbreviations for Recommended District/Area: UC = Urban Core APPROVED PLANT LIST Allowed Species Protect from sun and wind R = Residential I = Industrial Native* Moisture Rating (Low Moisture – High Moisture) P = Parks The following plant list has been established and approved by the A = All districts/areas (excluding natural areas) North Park Design Review Committee (DRC) for the Baseline Community. Pollinator** Sun Exposure Rating (No Sun – Full Sun) Any substitutions or variances from the following list must be submitted to the DRC for review and approval. * A Native Plant is defined as those native to the Rocky Mountain Inter-Mountain Region. **A Pollinator is defined as those that provide food and/or reproductive resources for pollinating animals, such as honeybees, native bees, butterflies, moths, beetles, flies and hummingbirds. SHRUBS Sun/Shade Moisture Scientific Name Common Name Flower Color Blooming Season Height Spread Notes Tolerance Needs SHRUBS Abronia fragrans Snowball Sand Verbena White 6-7 4-24" 4-24" R, P Greenish UC Agave americana Century Plant Late Spring, Early Summer 6’-12’ 6-10’ Yellow May not be reliably hardy, requires sandy/gritty soil P Alnus incana ssp. tenuifolia Thinleaf Alder Purple Early Spring 15-40’ 15-40’ Host plant, Spreads - more appropriate for parks, More tree-like; catkins through winter Amelanchier alnifolia Saskatoon Serviceberry White Mid Spring 4’-15’ 6’-8’ A Amelanchier canadensis Shadblow Serviceberry White Mid Spring 25’-30’ 15’-20’ A High habitat -

Approved Plant List

Approved Plant List Facts to Know INTRODUCTION: The Approved Tree and Plant List has been complied by highly-qualified experts in the field of horticulture and High Plains native plants, and it includes hundreds of species of plants and trees that are suited to the city’s environment. The list is to be used by property owners, developers, and the city as a standard for selecting native and adapted plant species to minimize maintenance costs, conserve water, and improve longevity. The following pages contain city-approved street tree species, prohibited species, and information regarding invasive species. This information should be used when preparing or updating a landscape plan. If you have any specific questions about this document, please contact the Community Development Department at 303-289-3683. Emerald Ash Borer Please be advised that Ash Borer (Pdodsesia syringae Harris) infestation concerns have been raised by the U.S. Forest Service and by Colorado State University for Ash trees along the Front Range and within Commerce City. The Ash Borer is an exotic insect from Asia that has been found feeding on Ash trees in the area. This insect feeds on all Ash species and can kill trees in one to three years. Therefore, in 2010 Commerce City’s Planning and Parks Planning Divisions issued a temporary, but indefinite, restriction on the use of Ash trees for developments within the city. The city’s policy regarding Ash trees is as follows: 1. Ash trees will not be approved for use in: • Any tree lawn or other right-of-way plantings that are associated with Site Plans, Development Plans, or Improvement Plans. -

Amur Chokecherry

Amur Chokecherry slide 37b slide 37a 360% 360% photo 37d 100% III-73 Amur Chokecherry Environmental Requirements (Prunus maackii) Soils Soil Texture - Adapted to a variety of soils. Soil pH - 5.0 to 7.5. General Description Windbreak Suitability Group - 1, 3, 4, 4C. A small to medium upright tree with white flowers and bright amber to deep coppery-orange bark which curls Cold Hardiness as it peels off. The distinctive bark provides year-round USDA Zone 3. accent to any landscape. Water Leaves and Buds Prefers moist, well-drained sites. Bud Arrangement - Alternate. Light Bud Color - Brown to amber-brown. Full sun. Bud Size - Small, 1/8 to 1/4 inch. Leaf Type and Shape - Simple, broad-elliptic to Uses oblong-ovate, acuminate tipped. Leaf Margins - Finely serrulate. Conservation/Windbreaks Leaf Surface - Gland-dotted beneath and slightly hairy Large shrub or small tree for farmstead windbreaks. on the veins. Wildlife Leaf Length - 2 to 3½ inches. Fruits are eaten by birds and small mammals. Leaf Width - 1 to 1½ inches. Nesting sites for song birds. Leaf Color - Medium to bright green; yellow fall color. Agroforestry Products Flowers and Fruits Food - Fruits can be used fresh or processed. Flower Type - Dense racemes. Medicinal - Seeds contain amygdalin which is processed Flower Color - Creamy-white. and has been used in cancer chemotherapy. Some Prunus Fruit Type - A drupe, fleshy outside with a stone inside, species were used for coughs, colds, and gout. A source 1/5 inch wide. of phloretin, an antibiotic. Fruit Color - Black, matures in July. Urban/Recreational Showy bark and flowers.