Gene Expression Within the Periaqueductal Gray Is Linked to Vocal Behavior and Early- Onset Parkinsonism in Pink1 Knockout Rats Cynthia A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyclin D1/Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 4 Interacts with Filamin a and Affects the Migration and Invasion Potential of Breast Cancer Cells

Published OnlineFirst February 28, 2010; DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1108 Tumor and Stem Cell Biology Cancer Research Cyclin D1/Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 4 Interacts with Filamin A and Affects the Migration and Invasion Potential of Breast Cancer Cells Zhijiu Zhong, Wen-Shuz Yeow, Chunhua Zou, Richard Wassell, Chenguang Wang, Richard G. Pestell, Judy N. Quong, and Andrew A. Quong Abstract Cyclin D1 belongs to a family of proteins that regulate progression through the G1-S phase of the cell cycle by binding to cyclin-dependent kinase (cdk)-4 to phosphorylate the retinoblastoma protein and release E2F transcription factors for progression through cell cycle. Several cancers, including breast, colon, and prostate, overexpress the cyclin D1 gene. However, the correlation of cyclin D1 overexpression with E2F target gene regulation or of cdk-dependent cyclin D1 activity with tumor development has not been identified. This suggests that the role of cyclin D1 in oncogenesis may be independent of its function as a cell cycle regulator. One such function is the role of cyclin D1 in cell adhesion and motility. Filamin A (FLNa), a member of the actin-binding filamin protein family, regulates signaling events involved in cell motility and invasion. FLNa has also been associated with a variety of cancers including lung cancer, prostate cancer, melanoma, human bladder cancer, and neuroblastoma. We hypothesized that elevated cyclin D1 facilitates motility in the invasive MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line. We show that MDA-MB-231 motility is affected by disturbing cyclin D1 levels or cyclin D1-cdk4/6 kinase activity. -

Role of Negative Regulation of Immune Signaling Pathways in Neutrophil Function

Role of negative regulation of immune signaling pathways in neutrophil function Veronica Azcutia *, Charles A. Parkos *, Jennifer C. Brazil * *Department of Pathology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 USA. Summary statement: Review on how PMN functions are negatively regulated by immune signaling pathways. Running title: Negative regulation of PMN function. Send correspondence to V.A and J.C.B, and the Editorial and Production Office information to V.A.: *Veronica Azcutia, Ph.D. Department of Pathology, University of Michigan. Biomedical Science Research Building (BSRB),109 Zina Pitcher Place, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 USA. This is the author manuscript accepted for publication and has undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this article as doi: 10.1002/JLB.3MIR0917-374R. This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved. Tel: (734)-936-1856, Fax: (734)-615-2331, e-Mail: [email protected] *Jennifer C. Brazil, Ph.D. Department of Pathology, University of Michigan. Biomedical Science Research Building (BSRB),109 Zina Pitcher Place, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 USA. Tel: (734)-936-1856, Fax: (734)-615-2331, e-Mail: [email protected] Key words: neutrophils, ITIM, inflammation. Total character count: 43,451; 2 Figures: Figure 1 and 2 are in color; 89 references; 144 words in Abstract; 12 words in summary statement. Abbreviations A(A2)AR = adenosine receptor BM = bone marrow CEACAM = carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule Csk = C-terminal Scr kinase fMLF = formyl-methionyl-leucyl phenylalanine peptide GAP = GTPase activating proteins GEF = guanine nucleotide exchange factor G-CSF = Granulocyte colony stimulating factor G-CSFR = Granulocyte colony stimulating factor receptor GPCR = G protein coupled receptor GRK = G protein coupled receptor kinase IBD = Inflammatory bowel disease ICAM-1 = Intracellular Adhesion molecule-1 2 This article is protected by copyright. -

Figure S1. DMD Module Network. the Network Is Formed by 260 Genes from Disgenet and 1101 Interactions from STRING. Red Nodes Are the Five Seed Candidate Genes

Figure S1. DMD module network. The network is formed by 260 genes from DisGeNET and 1101 interactions from STRING. Red nodes are the five seed candidate genes. Figure S2. DMD module network is more connected than a random module of the same size. It is shown the distribution of the largest connected component of 10.000 random modules of the same size of the DMD module network. The green line (x=260) represents the DMD largest connected component, obtaining a z-score=8.9. Figure S3. Shared genes between BMD and DMD signature. A) A meta-analysis of three microarray datasets (GSE3307, GSE13608 and GSE109178) was performed for the identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in BMD muscle biopsies as compared to normal muscle biopsies. Briefly, the GSE13608 dataset included 6 samples of skeletal muscle biopsy from healthy people and 5 samples from BMD patients. Biopsies were taken from either biceps brachii, triceps brachii or deltoid. The GSE3307 dataset included 17 samples of skeletal muscle biopsy from healthy people and 10 samples from BMD patients. The GSE109178 dataset included 14 samples of controls and 11 samples from BMD patients. For both GSE3307 and GSE10917 datasets, biopsies were taken at the time of diagnosis and from the vastus lateralis. For the meta-analysis of GSE13608, GSE3307 and GSE109178, a random effects model of effect size measure was used to integrate gene expression patterns from the two datasets. Genes with an adjusted p value (FDR) < 0.05 and an │effect size│>2 were identified as DEGs and selected for further analysis. A significant number of DEGs (p<0.001) were in common with the DMD signature genes (blue nodes), as determined by a hypergeometric test assessing the significance of the overlap between the BMD DEGs and the number of DMD signature genes B) MCODE analysis of the overlapping genes between BMD DEGs and DMD signature genes. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion Genes Data Set

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion genes data set PROBE Entrez Gene ID Celera Gene ID Gene_Symbol Gene_Name 160832 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 223658 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 212988 102 hCG40040.3 ADAM10 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 10 133411 4185 hCG28232.2 ADAM11 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 11 110695 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 195222 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 165344 8751 hCG20021.3 ADAM15 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 15 (metargidin) 189065 6868 null ADAM17 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17 (tumor necrosis factor, alpha, converting enzyme) 108119 8728 hCG15398.4 ADAM19 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 19 (meltrin beta) 117763 8748 hCG20675.3 ADAM20 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 20 126448 8747 hCG1785634.2 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 208981 8747 hCG1785634.2|hCG2042897 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 180903 53616 hCG17212.4 ADAM22 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 22 177272 8745 hCG1811623.1 ADAM23 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 23 102384 10863 hCG1818505.1 ADAM28 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 28 119968 11086 hCG1786734.2 ADAM29 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 29 205542 11085 hCG1997196.1 ADAM30 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 30 148417 80332 hCG39255.4 ADAM33 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 33 140492 8756 hCG1789002.2 ADAM7 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 7 122603 101 hCG1816947.1 ADAM8 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 8 183965 8754 hCG1996391 ADAM9 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 9 (meltrin gamma) 129974 27299 hCG15447.3 ADAMDEC1 ADAM-like, -

Anti-Inflammatory Role of Curcumin in LPS Treated A549 Cells at Global Proteome Level and on Mycobacterial Infection

Anti-inflammatory Role of Curcumin in LPS Treated A549 cells at Global Proteome level and on Mycobacterial infection. Suchita Singh1,+, Rakesh Arya2,3,+, Rhishikesh R Bargaje1, Mrinal Kumar Das2,4, Subia Akram2, Hossain Md. Faruquee2,5, Rajendra Kumar Behera3, Ranjan Kumar Nanda2,*, Anurag Agrawal1 1Center of Excellence for Translational Research in Asthma and Lung Disease, CSIR- Institute of Genomics and Integrative Biology, New Delhi, 110025, India. 2Translational Health Group, International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology, New Delhi, 110067, India. 3School of Life Sciences, Sambalpur University, Jyoti Vihar, Sambalpur, Orissa, 768019, India. 4Department of Respiratory Sciences, #211, Maurice Shock Building, University of Leicester, LE1 9HN 5Department of Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering, Islamic University, Kushtia- 7003, Bangladesh. +Contributed equally for this work. S-1 70 G1 S 60 G2/M 50 40 30 % of cells 20 10 0 CURI LPSI LPSCUR Figure S1: Effect of curcumin and/or LPS treatment on A549 cell viability A549 cells were treated with curcumin (10 µM) and/or LPS or 1 µg/ml for the indicated times and after fixation were stained with propidium iodide and Annexin V-FITC. The DNA contents were determined by flow cytometry to calculate percentage of cells present in each phase of the cell cycle (G1, S and G2/M) using Flowing analysis software. S-2 Figure S2: Total proteins identified in all the three experiments and their distribution betwee curcumin and/or LPS treated conditions. The proteins showing differential expressions (log2 fold change≥2) in these experiments were presented in the venn diagram and certain number of proteins are common in all three experiments. -

Cyclophilin B Facilitates the Replication of Orf Virus Kui Zhao1, Jida Li2, Wenqi He1, Deguang Song1, Ximu Zhang3, Di Zhang1, Yanlong Zhou1 and Feng Gao1,4*

Zhao et al. Virology Journal (2017) 14:114 DOI 10.1186/s12985-017-0781-x RESEARCH Open Access Cyclophilin B facilitates the replication of Orf virus Kui Zhao1, Jida Li2, Wenqi He1, Deguang Song1, Ximu Zhang3, Di Zhang1, Yanlong Zhou1 and Feng Gao1,4* Abstract Background: Viruses interact with host cellular factors to construct a more favourable environment for their efficient replication. Expression of cyclophilin B (CypB), a cellular peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase (PPIase), was found to be significantly up-regulated. Recently, a number of studies have shown that CypB is important in the replication of several viruses, including Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), hepatitis C virus (HCV) and human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV 16). However, the function of cellular CypB in ORFV replication has not yet been explored. Methods: Suppression subtractive hybridization (SSH) technique was applied to identify genes differentially expressed in the ORFV-infected MDBK cells at an early phase of infection. Cellular CypB was confirmed to be significantly up- regulated by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis and Western blotting. The role of CypB in ORFV infection was further determined using Cyclosporin A (CsA) and RNA interference (RNAi). Effect of CypB gene silencing on ORFV replication by 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) assay and qRT-PCR detection. Results: In the present study, CypB was found to be significantly up-regulated in the ORFV-infected MDBK cells at an early phase of infection. Cyclosporin A (CsA) exhibited suppressive effects on ORFV replication through the inhibition of CypB. Silencing of CypB gene inhibited the replication of ORFV in MDBK cells. -

CD Markers Are Routinely Used for the Immunophenotyping of Cells

ptglab.com 1 CD MARKER ANTIBODIES www.ptglab.com Introduction The cluster of differentiation (abbreviated as CD) is a protocol used for the identification and investigation of cell surface molecules. So-called CD markers are routinely used for the immunophenotyping of cells. Despite this use, they are not limited to roles in the immune system and perform a variety of roles in cell differentiation, adhesion, migration, blood clotting, gamete fertilization, amino acid transport and apoptosis, among many others. As such, Proteintech’s mini catalog featuring its antibodies targeting CD markers is applicable to a wide range of research disciplines. PRODUCT FOCUS PECAM1 Platelet endothelial cell adhesion of blood vessels – making up a large portion molecule-1 (PECAM1), also known as cluster of its intracellular junctions. PECAM-1 is also CD Number of differentiation 31 (CD31), is a member of present on the surface of hematopoietic the immunoglobulin gene superfamily of cell cells and immune cells including platelets, CD31 adhesion molecules. It is highly expressed monocytes, neutrophils, natural killer cells, on the surface of the endothelium – the thin megakaryocytes and some types of T-cell. Catalog Number layer of endothelial cells lining the interior 11256-1-AP Type Rabbit Polyclonal Applications ELISA, FC, IF, IHC, IP, WB 16 Publications Immunohistochemical of paraffin-embedded Figure 1: Immunofluorescence staining human hepatocirrhosis using PECAM1, CD31 of PECAM1 (11256-1-AP), Alexa 488 goat antibody (11265-1-AP) at a dilution of 1:50 anti-rabbit (green), and smooth muscle KD/KO Validated (40x objective). alpha-actin (red), courtesy of Nicola Smart. PECAM1: Customer Testimonial Nicola Smart, a cardiovascular researcher “As you can see [the immunostaining] is and a group leader at the University of extremely clean and specific [and] displays Oxford, has said of the PECAM1 antibody strong intercellular junction expression, (11265-1-AP) that it “worked beautifully as expected for a cell adhesion molecule.” on every occasion I’ve tried it.” Proteintech thanks Dr. -

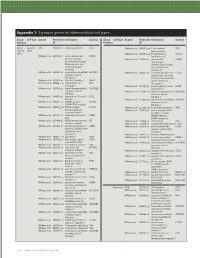

Technical Note, Appendix: an Analysis of Blood Processing Methods to Prepare Samples for Genechip® Expression Profiling (Pdf, 1

Appendix 1: Signature genes for different blood cell types. Blood Cell Type Source Probe Set Description Symbol Blood Cell Type Source Probe Set Description Symbol Fraction ID Fraction ID Mono- Lympho- GSK 203547_at CD4 antigen (p55) CD4 Whitney et al. 209813_x_at T cell receptor TRG nuclear cytes gamma locus cells Whitney et al. 209995_s_at T-cell leukemia/ TCL1A Whitney et al. 203104_at colony stimulating CSF1R lymphoma 1A factor 1 receptor, Whitney et al. 210164_at granzyme B GZMB formerly McDonough (granzyme 2, feline sarcoma viral cytotoxic T-lymphocyte- (v-fms) oncogene associated serine homolog esterase 1) Whitney et al. 203290_at major histocompatibility HLA-DQA1 Whitney et al. 210321_at similar to granzyme B CTLA1 complex, class II, (granzyme 2, cytotoxic DQ alpha 1 T-lymphocyte-associated Whitney et al. 203413_at NEL-like 2 (chicken) NELL2 serine esterase 1) Whitney et al. 203828_s_at natural killer cell NK4 (H. sapiens) transcript 4 Whitney et al. 212827_at immunoglobulin heavy IGHM Whitney et al. 203932_at major histocompatibility HLA-DMB constant mu complex, class II, Whitney et al. 212998_x_at major histocompatibility HLA-DQB1 DM beta complex, class II, Whitney et al. 204655_at chemokine (C-C motif) CCL5 DQ beta 1 ligand 5 Whitney et al. 212999_x_at major histocompatibility HLA-DQB Whitney et al. 204661_at CDW52 antigen CDW52 complex, class II, (CAMPATH-1 antigen) DQ beta 1 Whitney et al. 205049_s_at CD79A antigen CD79A Whitney et al. 213193_x_at T cell receptor beta locus TRB (immunoglobulin- Whitney et al. 213425_at Homo sapiens cDNA associated alpha) FLJ11441 fis, clone Whitney et al. 205291_at interleukin 2 receptor, IL2RB HEMBA1001323, beta mRNA sequence Whitney et al. -

Supplementary Table 9. Functional Annotation Clustering Results for the Union (GS3) of the Top Genes from the SNP-Level and Gene-Based Analyses (See ST4)

Supplementary Table 9. Functional Annotation Clustering Results for the union (GS3) of the top genes from the SNP-level and Gene-based analyses (see ST4) Column Header Key Annotation Cluster Name of cluster, sorted by descending Enrichment score Enrichment Score EASE enrichment score for functional annotation cluster Category Pathway Database Term Pathway name/Identifier Count Number of genes in the submitted list in the specified term % Percentage of identified genes in the submitted list associated with the specified term PValue Significance level associated with the EASE enrichment score for the term Genes List of genes present in the term List Total Number of genes from the submitted list present in the category Pop Hits Number of genes involved in the specified term (category-specific) Pop Total Number of genes in the human genome background (category-specific) Fold Enrichment Ratio of the proportion of count to list total and population hits to population total Bonferroni Bonferroni adjustment of p-value Benjamini Benjamini adjustment of p-value FDR False Discovery Rate of p-value (percent form) Annotation Cluster 1 Enrichment Score: 3.8978262119731335 Category Term Count % PValue Genes List Total Pop Hits Pop Total Fold Enrichment Bonferroni Benjamini FDR GOTERM_CC_DIRECT GO:0005886~plasma membrane 383 24.33290978 5.74E-05 SLC9A9, XRCC5, HRAS, CHMP3, ATP1B2, EFNA1, OSMR, SLC9A3, EFNA3, UTRN, SYT6, ZNRF2, APP, AT1425 4121 18224 1.18857065 0.038655922 0.038655922 0.086284383 UP_KEYWORDS Membrane 626 39.77128335 1.53E-04 SLC9A9, HRAS, -

Supplementary Material DNA Methylation in Inflammatory Pathways Modifies the Association Between BMI and Adult-Onset Non- Atopic

Supplementary Material DNA Methylation in Inflammatory Pathways Modifies the Association between BMI and Adult-Onset Non- Atopic Asthma Ayoung Jeong 1,2, Medea Imboden 1,2, Akram Ghantous 3, Alexei Novoloaca 3, Anne-Elie Carsin 4,5,6, Manolis Kogevinas 4,5,6, Christian Schindler 1,2, Gianfranco Lovison 7, Zdenko Herceg 3, Cyrille Cuenin 3, Roel Vermeulen 8, Deborah Jarvis 9, André F. S. Amaral 9, Florian Kronenberg 10, Paolo Vineis 11,12 and Nicole Probst-Hensch 1,2,* 1 Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, 4051 Basel, Switzerland; [email protected] (A.J.); [email protected] (M.I.); [email protected] (C.S.) 2 Department of Public Health, University of Basel, 4001 Basel, Switzerland 3 International Agency for Research on Cancer, 69372 Lyon, France; [email protected] (A.G.); [email protected] (A.N.); [email protected] (Z.H.); [email protected] (C.C.) 4 ISGlobal, Barcelona Institute for Global Health, 08003 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] (A.-E.C.); [email protected] (M.K.) 5 Universitat Pompeu Fabra (UPF), 08002 Barcelona, Spain 6 CIBER Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP), 08005 Barcelona, Spain 7 Department of Economics, Business and Statistics, University of Palermo, 90128 Palermo, Italy; [email protected] 8 Environmental Epidemiology Division, Utrecht University, Institute for Risk Assessment Sciences, 3584CM Utrecht, Netherlands; [email protected] 9 Population Health and Occupational Disease, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College, SW3 6LR London, UK; [email protected] (D.J.); [email protected] (A.F.S.A.) 10 Division of Genetic Epidemiology, Medical University of Innsbruck, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria; [email protected] 11 MRC-PHE Centre for Environment and Health, School of Public Health, Imperial College London, W2 1PG London, UK; [email protected] 12 Italian Institute for Genomic Medicine (IIGM), 10126 Turin, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +41-61-284-8378 Int. -

Whole Exome Sequencing in Families at High Risk for Hodgkin Lymphoma: Identification of a Predisposing Mutation in the KDR Gene

Hodgkin Lymphoma SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX Whole exome sequencing in families at high risk for Hodgkin lymphoma: identification of a predisposing mutation in the KDR gene Melissa Rotunno, 1 Mary L. McMaster, 1 Joseph Boland, 2 Sara Bass, 2 Xijun Zhang, 2 Laurie Burdett, 2 Belynda Hicks, 2 Sarangan Ravichandran, 3 Brian T. Luke, 3 Meredith Yeager, 2 Laura Fontaine, 4 Paula L. Hyland, 1 Alisa M. Goldstein, 1 NCI DCEG Cancer Sequencing Working Group, NCI DCEG Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory, Stephen J. Chanock, 5 Neil E. Caporaso, 1 Margaret A. Tucker, 6 and Lynn R. Goldin 1 1Genetic Epidemiology Branch, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD; 2Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD; 3Ad - vanced Biomedical Computing Center, Leidos Biomedical Research Inc.; Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, Frederick, MD; 4Westat, Inc., Rockville MD; 5Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD; and 6Human Genetics Program, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA ©2016 Ferrata Storti Foundation. This is an open-access paper. doi:10.3324/haematol.2015.135475 Received: August 19, 2015. Accepted: January 7, 2016. Pre-published: June 13, 2016. Correspondence: [email protected] Supplemental Author Information: NCI DCEG Cancer Sequencing Working Group: Mark H. Greene, Allan Hildesheim, Nan Hu, Maria Theresa Landi, Jennifer Loud, Phuong Mai, Lisa Mirabello, Lindsay Morton, Dilys Parry, Anand Pathak, Douglas R. Stewart, Philip R. Taylor, Geoffrey S. Tobias, Xiaohong R. Yang, Guoqin Yu NCI DCEG Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory: Salma Chowdhury, Michael Cullen, Casey Dagnall, Herbert Higson, Amy A.