Strategic Methods Utilized by Small Business Development Centers in the United States and Its’ Territories to Deliver Educational Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program and Abstracts of 2017 Congress / Programme Et Résumés

1 Sponsors | Commanditaires Gold Sponsors | Commanditaires d’or Silver Sponsors | Commanditaires d’argent Other Sponsors | Les autres Commanditaires 2 Contents Sponsors | Commanditaires .......................................................................................................................... 2 Welcome from the Premier of Ontario .......................................................................................................... 5 Bienvenue du premier ministre de l'Ontario .................................................................................................. 6 Welcome from the Mayor of Toronto ............................................................................................................ 7 Mot de bienvenue du maire de Toronto ........................................................................................................ 8 Welcome from the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard ...................................... 9 Mot de bienvenue de ministre des Pêches, des Océans et de la Garde côtière canadienne .................... 10 Welcome from the Minister of Environment and Climate Change .............................................................. 11 Mot de bienvenue du Ministre d’Environnement et Changement climatique Canada ................................ 12 Welcome from the President of the Canadian Meteorological and Oceanographic Society ...................... 13 Mot de bienvenue du président de la Société canadienne de météorologie et d’océanographie ............. -

Special Catalogue Milestones of Lunar Mapping and Photography Four Centuries of Selenography on the Occasion of the 50Th Anniversary of Apollo 11 Moon Landing

Special Catalogue Milestones of Lunar Mapping and Photography Four Centuries of Selenography On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 moon landing Please note: A specific item in this catalogue may be sold or is on hold if the provided link to our online inventory (by clicking on the blue-highlighted author name) doesn't work! Milestones of Science Books phone +49 (0) 177 – 2 41 0006 www.milestone-books.de [email protected] Member of ILAB and VDA Catalogue 07-2019 Copyright © 2019 Milestones of Science Books. All rights reserved Page 2 of 71 Authors in Chronological Order Author Year No. Author Year No. BIRT, William 1869 7 SCHEINER, Christoph 1614 72 PROCTOR, Richard 1873 66 WILKINS, John 1640 87 NASMYTH, James 1874 58, 59, 60, 61 SCHYRLEUS DE RHEITA, Anton 1645 77 NEISON, Edmund 1876 62, 63 HEVELIUS, Johannes 1647 29 LOHRMANN, Wilhelm 1878 42, 43, 44 RICCIOLI, Giambattista 1651 67 SCHMIDT, Johann 1878 75 GALILEI, Galileo 1653 22 WEINEK, Ladislaus 1885 84 KIRCHER, Athanasius 1660 31 PRINZ, Wilhelm 1894 65 CHERUBIN D'ORLEANS, Capuchin 1671 8 ELGER, Thomas Gwyn 1895 15 EIMMART, Georg Christoph 1696 14 FAUTH, Philipp 1895 17 KEILL, John 1718 30 KRIEGER, Johann 1898 33 BIANCHINI, Francesco 1728 6 LOEWY, Maurice 1899 39, 40 DOPPELMAYR, Johann Gabriel 1730 11 FRANZ, Julius Heinrich 1901 21 MAUPERTUIS, Pierre Louis 1741 50 PICKERING, William 1904 64 WOLFF, Christian von 1747 88 FAUTH, Philipp 1907 18 CLAIRAUT, Alexis-Claude 1765 9 GOODACRE, Walter 1910 23 MAYER, Johann Tobias 1770 51 KRIEGER, Johann 1912 34 SAVOY, Gaspare 1770 71 LE MORVAN, Charles 1914 37 EULER, Leonhard 1772 16 WEGENER, Alfred 1921 83 MAYER, Johann Tobias 1775 52 GOODACRE, Walter 1931 24 SCHRÖTER, Johann Hieronymus 1791 76 FAUTH, Philipp 1932 19 GRUITHUISEN, Franz von Paula 1825 25 WILKINS, Hugh Percy 1937 86 LOHRMANN, Wilhelm Gotthelf 1824 41 USSR ACADEMY 1959 1 BEER, Wilhelm 1834 4 ARTHUR, David 1960 3 BEER, Wilhelm 1837 5 HACKMAN, Robert 1960 27 MÄDLER, Johann Heinrich 1837 49 KUIPER Gerard P. -

Thermal and Crustal Evolution of Mars Steven A

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 107, NO. E7, 10.1029/2001JE001801, 2002 Thermal and crustal evolution of Mars Steven A. Hauck II1 and Roger J. Phillips McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences and Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Washington University, Saint Louis, Missouri, USA Received 11 October 2001; revised 4 February 2002; accepted 11 February 2002; published 16 July 2002. [1] We present a coupled thermal-magmatic model for the evolution of Mars’ mantle and crust that may be consistent with estimates of the average crustal thickness and crustal growth rate. By coupling a simple parameterized model of mantle convection to a batch- melting model for peridotite, we can investigate potential conditions and evolutionary paths of the crust and mantle in a coupled thermal-magmatic system. On the basis of recent geophysical and geochemical studies, we constrain our models to have average crustal thicknesses between 50 and 100 km that were mostly formed by 4 Ga. Our nominal model is an attempt to satisfy these constraints with a relatively simple set of conditions. Key elements of this model are the inclusion of the energetics of melting, a wet (weak) mantle rheology, self-consistent fractionation of heat-producing elements to the crust, and a near- chondritic abundance of those elements. The latent heat of melting mantle material is a small (percent level) contributor to the total planetary energy budget over 4.5 Gyr but is crucial for constraining the thermal and magmatic history of Mars. Our nominal model predicts an average crustal thickness of 62 km that was 73% emplaced by 4 Ga. -

March 21–25, 2016

FORTY-SEVENTH LUNAR AND PLANETARY SCIENCE CONFERENCE PROGRAM OF TECHNICAL SESSIONS MARCH 21–25, 2016 The Woodlands Waterway Marriott Hotel and Convention Center The Woodlands, Texas INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT Universities Space Research Association Lunar and Planetary Institute National Aeronautics and Space Administration CONFERENCE CO-CHAIRS Stephen Mackwell, Lunar and Planetary Institute Eileen Stansbery, NASA Johnson Space Center PROGRAM COMMITTEE CHAIRS David Draper, NASA Johnson Space Center Walter Kiefer, Lunar and Planetary Institute PROGRAM COMMITTEE P. Doug Archer, NASA Johnson Space Center Nicolas LeCorvec, Lunar and Planetary Institute Katherine Bermingham, University of Maryland Yo Matsubara, Smithsonian Institute Janice Bishop, SETI and NASA Ames Research Center Francis McCubbin, NASA Johnson Space Center Jeremy Boyce, University of California, Los Angeles Andrew Needham, Carnegie Institution of Washington Lisa Danielson, NASA Johnson Space Center Lan-Anh Nguyen, NASA Johnson Space Center Deepak Dhingra, University of Idaho Paul Niles, NASA Johnson Space Center Stephen Elardo, Carnegie Institution of Washington Dorothy Oehler, NASA Johnson Space Center Marc Fries, NASA Johnson Space Center D. Alex Patthoff, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Cyrena Goodrich, Lunar and Planetary Institute Elizabeth Rampe, Aerodyne Industries, Jacobs JETS at John Gruener, NASA Johnson Space Center NASA Johnson Space Center Justin Hagerty, U.S. Geological Survey Carol Raymond, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Lindsay Hays, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Paul Schenk, -

Testing Hypotheses for the Origin of Steep Slope of Lunar Size-Frequency Distribution for Small Craters

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Earth Planets Space, 55, 39–51, 2003 Testing hypotheses for the origin of steep slope of lunar size-frequency distribution for small craters Noriyuki Namiki1 and Chikatoshi Honda2 1Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Kyushu University, Hakozaki 6-10-1, Higashi-ku, Fukuoka 812-8581, Japan 2The Institute of Space and Astronautical Science, Yoshinodai 3-1-1, Sagamihara 229-8510, Japan (Received June 13, 2001; Revised June 24, 2002; Accepted January 6, 2003) The crater size-frequency distribution of lunar maria is characterized by the change in slope of the population between 0.3 and 4 km in crater diameter. The origin of the steep segment in the distribution is not well understood. Nonetheless, craters smaller than a few km in diameter are widely used to estimate the crater retention age for areas so small that the number of larger craters is statistically insufficient. Future missions to the moon, which will obtain high resolution images, will provide a new, large data set of small craters. Thus it is important to review current hypotheses for their distributions before future missions are launched. We examine previous and new arguments and data bearing on the admixture of endogenic and secondary craters, horizontal heterogeneity of the substratum, and the size-frequency distribution of the primary production function. The endogenic crater and heterogeneous substratum hypotheses are seen to have little evidence in their favor, and can be eliminated. The primary production hypothesis fails to explain a wide variation of the size-frequency distribution of Apollo panoramic photographs. -

Appendix I Lunar and Martian Nomenclature

APPENDIX I LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE A large number of names of craters and other features on the Moon and Mars, were accepted by the IAU General Assemblies X (Moscow, 1958), XI (Berkeley, 1961), XII (Hamburg, 1964), XIV (Brighton, 1970), and XV (Sydney, 1973). The names were suggested by the appropriate IAU Commissions (16 and 17). In particular the Lunar names accepted at the XIVth and XVth General Assemblies were recommended by the 'Working Group on Lunar Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr D. H. Menzel. The Martian names were suggested by the 'Working Group on Martian Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr G. de Vaucouleurs. At the XVth General Assembly a new 'Working Group on Planetary System Nomenclature' was formed (Chairman: Dr P. M. Millman) comprising various Task Groups, one for each particular subject. For further references see: [AU Trans. X, 259-263, 1960; XIB, 236-238, 1962; Xlffi, 203-204, 1966; xnffi, 99-105, 1968; XIVB, 63, 129, 139, 1971; Space Sci. Rev. 12, 136-186, 1971. Because at the recent General Assemblies some small changes, or corrections, were made, the complete list of Lunar and Martian Topographic Features is published here. Table 1 Lunar Craters Abbe 58S,174E Balboa 19N,83W Abbot 6N,55E Baldet 54S, 151W Abel 34S,85E Balmer 20S,70E Abul Wafa 2N,ll7E Banachiewicz 5N,80E Adams 32S,69E Banting 26N,16E Aitken 17S,173E Barbier 248, 158E AI-Biruni 18N,93E Barnard 30S,86E Alden 24S, lllE Barringer 29S,151W Aldrin I.4N,22.1E Bartels 24N,90W Alekhin 68S,131W Becquerei -

Download New Glass Review 21

NewG lass The Corning Museum of Glass NewGlass Review 21 The Corning Museum of Glass Corning, New York 2000 Objects reproduced in this annual review Objekte, die in dieser jahrlich erscheinenden were chosen with the understanding Zeitschrift veroffentlicht werden, wurden unter that they were designed and made within der Voraussetzung ausgewahlt, dass sie in- the 1999 calendar year. nerhalb des Kalenderjahres 1999 entworfen und gefertigt wurden. For additional copies of New Glass Review, Zusatzliche Exemplare der New Glass please contact: Review konnen angefordert werden bei: The Corning Museum of Glass Buying Office One Corning Glass Center Corning, New York 14830-2253 Telephone: (607) 974-6479 Fax: (607) 974-7365 E-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved, 2000 Alle Rechte vorbehalten, 2000 The Corning Museum of Glass The Corning Museum of Glass Corning, New York 14830-2253 Corning, New York 14830-2253 Printed in Frechen, Germany Gedruckt in Frechen, Bundesrepublik Deutschland Standard Book Number 0-87290-147-5 ISSN: 0275-469X Library of Congress Catalog Card Number Aufgefuhrt im Katalog der Library of Congress 81-641214 unter der Nummer 81-641214 Table of Contents/In halt Page/Seite Jury Statements/Statements der Jury 4 Artists and Objects/Kunstlerlnnen und Objekte 16 1999 in Review/Ruckblick auf 1999 36 Bibliography/Bibliografie 44 A Selective Index of Proper Names and Places/ Ausgewahltes Register von Eigennamen und Orten 73 Jury Statements Here is 2000, and where is art? Hier ist das Jahr 2000, und wo ist die Kunst? Although more people believe they make art than ever before, it is a Obwohl mehr Menschen als je zuvor glauben, sie machen Kunst, "definitionless" word about which a lot of people disagree. -

Installers.Pdf

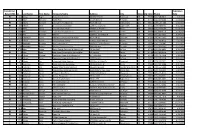

Initial (I) or Expiration Recert (RI) Id Last Name First Sept Name Company Name Address City State Zip Code Phone Date RI 212 Abbas Roger Abbas Construction 6827 NE 33rd St Redmond OR 97756 (541) 548-6812 2/3/2024 I 2888 Adair Benjamin Septic Pros 1751 N Main st Prineville OR 97754 (541) 359-8466 5/10/2024 RI 727 Adams Kenneth Ken Adams Plumbing Inc 906 N 9th Ave Walla Walla WA 99362 (509) 529-7389 6/23/2023 RI 884 Adcock Dean Tri County Construction 22987 SE Dowty Rd Eagle Creek OR 97022 (503) 948-0491 9/25/2023 I 2592 Adelt Georg Cascade Valley Septic 17360 Star Thistle Ln Bend OR 97703 (541) 337-4145 11/18/2022 I 2994 Agee Jetamiah Leavn Trax Excavation LLC 50020 Collar Dr. La Pine OR 97739 (541) 640-3115 9/13/2024 I 2502 Aho Brennon BRX Inc 33887 SE Columbus St Albany OR 97322 (541) 953-7375 6/24/2022 I 2392 Albertson Adam Albertson Construction & Repair 907 N 6th St Lakeview OR 97630 (541) 417-1025 12/3/2021 RI 831 Albion Justin Poe's Backhoe Service 6590 SE Seven Mile Ln Albany OR 97322 (541) 401-8752 7/25/2022 I 2732 Alexander Brandon Blux Excavation LLC 10150 SE Golden Eagle Dr Prineville OR 97754 (541) 233-9682 9/21/2023 RI 144 Alexander Robert Red Hat Construction, Inc. 560 SW B Ave Corvallis OR 97333 (541) 753-2902 2/17/2024 I 2733 Allen Justan South County Concrete & Asphalt, LLC PO Box 2487 La Pine OR 97739 (541) 536-4624 9/21/2023 RI 74 Alley Dale Back Street Construction Corporation PO Box 350 Culver OR 97734 (541) 480-0516 2/17/2024 I 2449 Allison Michael Deschutes Property Solultions, LLC 15751 Park Dr La Pine OR 97739 (541) 241-4298 5/20/2022 I 2448 Allison Tisha Deschutes Property Solultions, LLC 15751 Park Dr La Pine OR 97739 (541) 241-4298 5/20/2022 RI 679 Alman Jay Integrated Water Services 4001 North Valley Dr. -

May 2017 Nhsca Duals 92 Elementary 92 Middle

MAY 2017 NHSCA DUALS 60 MATS 92 ELEMENTARY 92 MIDDLE SCHOOL 184 HIGH SCHOOL 1233 MS WRESTLERS MS Ms 4m First Name Last Name Info 1 75 Luke Seagraves 6 2 80 Isaac Landis 3 85 Micah Crenshaw 7 4 90 Karson Kline 7 PJW State Qualifier 5 90 Mason Prinkey 8 6 100 Taylor Weaver 7 PJW State 3rd place, MAWA Eastern National 4th place, Northeast region freestyle and Greco-Roman 2nd Multiple time PJW State Qualifier, PJW State runner-up, PJW Empire 7th place, NUWAY National 7 105 Nolan Fenton 7 Champio 8 112 Cole Felker 7 9 119 Mark McGonigal 7 Multiple time PJW State Placewinner 6 time PJW State Qualifier, 5 time PJW placewinner, MAWA Eastern National Chamption, TOC multiple 10 127 Hunter Weitosh 8 ti 11 135 Hayes Jones 8 Inter County Conference Champion 12 135 Dakota Mascho 7 4 time PJW State Qualifier, PJW 3rd place, PJW runner-up, PJW State Champion 13 154 Ethan Yingling 8 Multiple time PJW State Qualifier 14 180 Conner Davis 15 180 Andrew Erskine MS Ms 84 Athletes First Name Last Name Info 1 80 Josh Domino 2 90 Keegan Herbst 3 95 Daniel Taylor 4 100 Kade Bradbury 5 100 Anakin Burks 6 112 Buddy Stine 7 119 Nick Nazzaro 8 127 Jaylon Burks 9 127 Naomi Vaughn 10 142 Ben Richardson 11 154 Griffin Symthers Ms All American MS First Name Last Name Info Wrestling Club 1 75 Nathan Pelesky 2 80 Dylan Coy 7th 3 85 Owen Reinsel 4 90 Luke Geibig MS Ms 4m First Name Last Name Info 5 95 Noah Teeter 6 100 Kris Oddo 7 105 Tony Salopek 8 112 Tyler Cymmerman 9 119 John Alteri 10 127 Shawn Getty 11 135 Brody Kunselman 12 142 Hudson Holbay 13 154 Dayton Pitzer 14 165 Jake Sabol 15 230 Cullen Lynch MS Ms Battlezone Black First Name Last Name Info 1 75 Codie Cuerbo 2017 Junior High State Placer, 4xGrade School State Placer, 9-1 Jr. -

The Case for Rainfall on a Warm, Wet Early Mars Robert A

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 107, NO. E11, 5111, doi:10.1029/2001JE001505, 2002 The case for rainfall on a warm, wet early Mars Robert A. Craddock Center for Earth and Planetary Studies, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, District of Columbia, USA Alan D. Howard Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, USA Received 11 April 2001; revised 10 April 2002; accepted 10 June 2002; published 23 November 2002. [1] Valley networks provide compelling evidence that past geologic processes on Mars were different than those seen today. The generally accepted paradigm is that these features formed from groundwater circulation, which may have been driven by differential heating induced by magmatic intrusions, impact melt, or a higher primordial heat flux. Although such mechanisms may not require climatic conditions any different than today’s, they fail to explain the large amount of recharge necessary for maintaining valley network systems, the spatial patterns of erosion, or how water became initially situated in the Martian regolith. In addition, there are no clear surface manifestations of any geothermal systems (e.g., mineral deposits or phreatic explosion craters). Finally, these models do not explain the style and amount of crater degradation. To the contrary, analyses of degraded crater morphometry indicate modification occurred from creep induced by rain splash combined with surface runoff and erosion; the former process appears to have continued late into Martian history. A critical analysis of the morphology and drainage density of valley networks based on Mars Global Surveyor data shows that these features are, in fact, entirely consistent with rainfall and surface runoff. -

Download Preprint

This is a non-peer-reviewed preprint submitted to EarthArXiv Global inventories of inverted stream channels on Earth and Mars Abdallah S. Zakia*, Colin F. Painb, Kenneth S. Edgettc, Sébastien Castelltorta a Department of Earth Sciences, University of Geneva, Rue des Maraîchers 13, 1205 Geneva, Switzerland. b MED_Soil, Departamento de Cristlografía, Mineralogía y Quimica Agrícola, Universidad de Sevilla, Calle Profesor García González s/n, 41012 Sevilla, Spain. c Malin Space Science Systems, Inc., P.O. Box 910148, San Diego, CA 92191, USA Corresponding Author: a* Department of Earth Sciences, University of Geneva, Rue des Maraîchers 13, 1205 Geneva, Switzerland. ([email protected]) ABSTRACT Data from orbiting and landed spacecraft have provided vast amounts of information regarding fluvial and fluvial-related landforms and sediments on Mars. One variant of these landforms are sinuous ridges that have been interpreted to be remnant evidence for ancient fluvial activity, observed at hundreds of martian locales. In order to further understanding of these martian landforms, this paper inventories the 107 known and unknown inverted channel sites on Earth; these offer 114 different examples that consist of materials ranging in age from Upper Ordovician to late Holocene. These examples record several climatic events from the Upper Ordovician glaciation to late Quaternary climate oscillation. These Earth examples include inverted channels in deltaic and alluvial fan sediment, providing new analogs to their martian counterparts. This global -

Our Evolving Understanding of Aeolian Bedforms, Based on Observation Of

Aeolian Research 26 (2017) 5–27 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Aeolian Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/aeolia Review Our evolving understanding of aeolian bedforms, based on observation of dunes on different worlds ⇑ Serina Diniega a, , Mikhail Kreslavsky b, Jani Radebaugh c, Simone Silvestro d,e, Matt Telfer f, Daniela Tirsch g a Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Dr., Pasadena, CA 91109, USA b Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of California – Santa Cruz, 1156 High Str., Santa Cruz, CA 95064, USA c Department of Geological Sciences, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602, USA d INAF Osservatorio Astronomico di Capodimonte, Via Moiariello 16, 80131 Napoli, Italy e Carl Sagan Center, SETI Institute, 189 N Bernardo Ave, Mountain View, CA 94043, USA f SOGEES, University of Plymouth, Drake Circus, Plymouth, Devon PL4 8AA, UK g Institute of Planetary Research, German Aerospace Center (DLR), Rutherfordstrasse 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany article info abstract Article history: Dunes, dune fields, and ripples are unique and useful records of the interaction between wind and gran- Received 5 April 2016 ular materials – finding such features on a planetary surface immediately suggests certain information Revised 30 September 2016 about climate and surface conditions (at least during the dunes’ formation and evolution). Accepted 4 October 2016 Additionally, studies of dune characteristics under non-Earth conditions allow for ‘‘tests” of aeolian pro- Available online 24 October 2016 cess models based primarily on observations of terrestrial features and dynamics, and refinement of the models to include consideration of a wider range of environmental and planetary conditions.