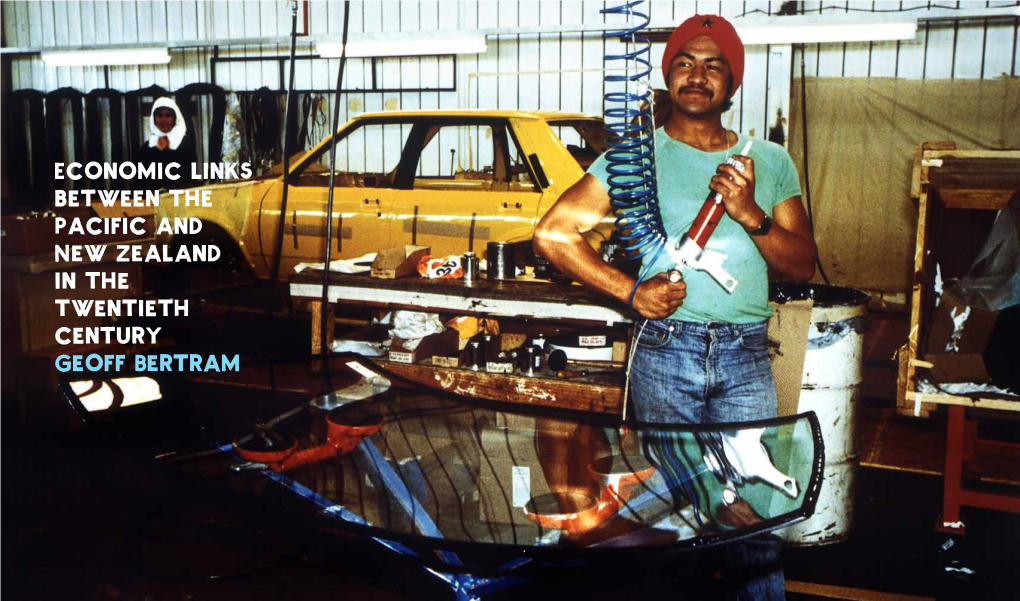

Economic Links Between the Pacific and New Zealand in the Twentieth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interim Report 2009

TVNZ Interim Report FY2009 CONTENTS CHAIRMAN’S INTRODUCTION........................................................3 CHIEF EXECUTIVE’S OVERVIEW........................................................4 INTERIM FINANCIAL STATEMENTS...................................................6 DIRECT GOVERNMENT FUNDING.................................................14 CHARTER PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT ...................................16 TVNZ BOARD AND MANAGEMENT DIRECTORY..........................23 2 TVNZ Interim Report FY2009 CHAIRMAN’S INTRODUCTION TVNZ has achieved a satisfactory result for the first six months of the 2009 financial year, reporting earnings (before interest, tax and financial instruments) of $27.7 million compared to $32.3 million in the same period the previous year. The after tax profit of $18.2 million for the period compares with $20.6 million for the prior period. While this is a pleasing result in the circumstances the impact of the global economic downturn is already apparent and, like all other businesses in 2009, TVNZ will face significant constraints due to worsening conditions. We expect the remainder of the fiscal year to be tough, and are prepared for this to continue into the 2010 year. Sir John Anderson Chairman 3 TVNZ Interim Report FY2009 CHIEF EXECUTIVE’S OVERVIEW Two years ago TVNZ began the hard work of turning the organisation into a contemporary, streamlined and efficient digital media company with a long term future – rather than a simple television broadcaster. The result of this effort became visible at the end of the last financial year, when the company worked its way back into the black, with a return on shareholders equity that was better than most SOEs and Crown-owned Companies as well as many publicly listed companies. The current half-year result is a validation of that approach. -

Incarceration, Migration and Indigenous Sovereignty

Space, Race, Bodies is a research collective focused on the connections between racisms, geography, and activist and theoretical accounts of embodiment. A number of events and research projects have been hosted under this theme, including the Incarceration, conference and workshops from which this booklet emerged, Space, Race, Bodies II: Sovereignty and Migration in a Carceral Age. Incarceration, Migration and Indigenous Sovereignty: Thoughts on Existence and Resistance Migration and in Racist Times responds to the current and ongoing histories of the incarceration of Indigenous peoples, migrants, and communities of colour. One of its key aims is to think about how prisons and their institutional operations are not marginal to everyday spaces, social relations, and politics. Rather the complex set of practices Indigenous around policing, detaining, and building and maintaining prisons and detention cen- tres are intimately connected to the way we understand space and place, how we understand ourselves and our families in relation to categories of criminal or inno- cent, and whether we feel secure or at home in the country we reside. Sovereignty: School of Indigenous Australian Studies Thoughts on Existence and Charles Sturt University Locked Bag 49 Resistance in Racist Times Dubbo NSW 2830 www.spaceracebodies.com Australia Edited by Holly Randell-Moon Incarceration, Migration and Indigenous Sovereignty: Thoughts on Existence and Resistance in Racist Times Edited by Holly Randell-Moon Second edition published in 2019 by Space, Race, Bodies School of Indigenous Australian Studies Charles Sturt University Locked Bag 49 Dubbo NSW 2830 Australia www.spaceracebodies.com ISBN 978-0-473-41840-3 Space, Race, Bodies Incarceration, Migration and Indigenous Sovereignty: Thoughts on Existence and Resistance in Racist Times Format Softcover Publication Date 11/2019 Layout, typesetting, cover design and printing by MCK Design & Print Space, Race, Bodies logo design by Mahdis Azarmandi. -

Fighting Brings Destruction to Afghan Cities Residents in Lashkar Gah Fighting Pitched Battles with Taleban

Established 1961 7 International Monday, August 2, 2021 ‘Bodies on the streets’: Fighting brings destruction to Afghan cities Residents in Lashkar Gah fighting pitched battles with Taleban KABUL: Families abandoned their homes in droves, ‘Situation getting worse’ air strikes rained down on neighborhoods and bod- In Lashkar Gah, resident Hazrat Omar Shirzad ies filled the streets as the Taleban took their fight was livid after the Taleban forced him out of his to Afghanistan’s cities over the weekend, starting a house to take shelter from the air strikes. “The new bloody chapter in the country’s long war. Islamic Emirate set the earth ablaze and the Residents in the southern city of Lashkar Gah said republic put the sky on fire. Nobody cares about the Taleban were fighting pitched battles from the nation,” said Shirzad. Fighting was also “street to street” with Afghan security forces and reported in Herat near the border with Iran to the had surrounded the police headquarters and gover- west for a third straight day, where militants nor’s office. swarmed the outskirts of the capital. “With every “The aircraft are bombing the city every minute. passing day the security situation is getting Every inch of the city has been bombed,” Badshah worse,” said Agha Reza, a businessman in Herat. Khan, a resident of Lashkar Gah, the capital of “There is a 90 percent chance Herat city will col- Helmand province, told AFP by phone. “You can see lapse to the Taleban,” he warned, saying that it dead bodies on the streets. There are bodies of lacked a steady supply of electricity and key people in the main square,” he added. -

A Perspective on the Changing Role of Pacific Islanders in New Zealand

Intrepid Journey – A Perspective on the Changing Role of Pacific Islanders in New Zealand Judith Taumuafono 2007 This thesis is submitted to Auckland University of Technology in partial fulfilment of the degree of Master of Arts (Communications Studies) TABLE OF CONTENTS Attestation of Authorship………………………………………………………………………………….4 Dedication………………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 Glossary………………………………………………………………………………………………………………6 Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………………………….7 Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………………………………8 i. Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………..9 Approach and scope of thesis………………………………………………………………….10 Method of enquiry……………………………………………………………………………………11 Thesis structure……………………………………………………………………………………….12 1. In the beginning – New Zealand the land of opportunity……………………14 A look at the origins of New Zealand’s relationship with Pacific Island nations…………………………………………………………………………………………………….14 The early browning of Aotearoa: New Zealand the land of milk and honey……………………………………………………………………………………………………….17 Unravelling the theoretical approach to international immigration………19 The Muldoon years…………………………………………………………………………………..21 The early influence of the media in the portrayal of Pacific Islanders….24 Reading between the frames…………………………………………………………………..26 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………………..34 2. Beyond the controversial overstayers’ campaign: the evolution of Pacific Islanders in New Zealand’s mainstream media……………………….35 State of the nation…………………………………………………………………………………..35 -

Diplomacy and the Pursuit of Regional Security

ISSN 1172-3416 MACMILLAN BROWN CENTRE FOR PACIFIC STUDIES PACIFIC POLICY BRIEF 2016/7 iplomacy and the pursuit of regional security D 1 Michael Powles Policy summary of paper presented at the regional conference on Rethinking regional security: Nexus between research and policy, November 25-26, 2015, University of Canterbury. A partnership between Macmillan Brown Center for Pacific Studies (University of Canterbury), Australian National University, United National Development Program and International Political Science Association 1 Michael Powles is a former New Zealand diplomat. 1 of 4 ost significant threats to security in For New Zealand to have significant the Pacific Islands region today are influence in support of regional security, M internal rather than external. One has depends on the quality of our diplomacy and only to look at the extraordinary situation the nature of the policies being pursued. So today in Nauru, the governance issues in the question I would like to raise with you is Papua New Guinea, the constitutional whether and how New Zealand diplomacy concerns in Vanuatu, and the dominance of could be improved in our home region. the military in Fiji. And in considering them, we need to remember that the Biketawa At the conference in Apia this year which I Declaration, agreed 16 years ago now, mentioned earlier, a very senior regional provides a mechanism that can be used to official, a Pacific Islander who has been combat threats to security in the region, positive about New Zealand's role in the including internal problems. Pacific over many years, asked me whether New Zealanders were aware how unpopular Some years ago, it was thought by many that their country was in the Pacific Islands these China would come to pose a significant threat days. -

27-Page Printable

Breaking News English.com Ready-to-Use English Lessons by Sean Banville “1,000 IDEAS & ACTIVITIES Thousands more free lessons FOR LANGUAGE TEACHERS” from Sean's other websites breakingnewsenglish.com/book.html www.freeeslmaterials.com/sean_banville_lessons.html Level 3 - 4th August, 2021 New Zealand apologizes for 70s immigration raids FREE online quizzes, mp3 listening and more for this lesson here: https://breakingnewsenglish.com/2108/210804-dawn-raids.html Contents The Article 2 Discussion (Student-Created Qs) 15 Warm-Ups 3 Language Work (Cloze) 16 Vocabulary 4 Spelling 17 Before Reading / Listening 5 Put The Text Back Together 18 Gap Fill 6 Put The Words In The Right Order 19 Match The Sentences And Listen 7 Circle The Correct Word 20 Listening Gap Fill 8 Insert The Vowels (a, e, i, o, u) 21 Comprehension Questions 9 Punctuate The Text And Add Capitals 22 Multiple Choice - Quiz 10 Put A Slash ( / ) Where The Spaces Are 23 Role Play 11 Free Writing 24 After Reading / Listening 12 Academic Writing 25 Student Survey 13 Homework 26 Discussion (20 Questions) 14 Answers 27 Please try Levels 0, 1 and 2 (they are easier). Twitter twitter.com/SeanBanville Facebook www.facebook.com/pages/BreakingNewsEnglish/155625444452176 THE ARTICLE From https://breakingnewsenglish.com/2108/210804-dawn-raids.html The Prime Minister of New Zealand Jacinda Ardern has apologized to Pacific Islanders for an immigration policy in the early 1970s. The policy was known as the Dawn Raids. These involved police with dogs waking up Pacific Islanders in the early hours of the morning to deport them. Pacific Islanders are from islands in the South Pacific such as Tahiti, Tonga, Samoa and Fiji. -

View Sample Pages of Tangata O Le Moana

Edited by Sean Mallon, Kolokesa Māhina-Tuai and Damon Salesa First published in New Zealand in 2012 by Te Papa Press, P O Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand Text © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa and the contributors Images © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa or as credited This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism, or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, without the prior permission of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. TE PAPA® is the trademark of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Te Papa Press is an imprint of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Tangata o le moana : New Zealand and the people of the Pacific / edited by Sean Mallon, Kolokesa Māhina-Tuai and Damon Salesa. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-877385-72-8 [1. Pacific Islanders—New Zealand. 2. Pacific Islanders—New Zealand—History.] I. Mallon, Sean. II. Māhina-Tuai, Kolokesa Uafā. III. Salesa, Damon Ieremia, 1972- IV. Title. 305.8995093—dc 22 Design by Spencer Levine Digital imaging by Jeremy Glyde Printed by Everbest Printing Co, China Cover: All images are selected from the pages of Tangata o le Moana. Back cover: Tokelauans leaving for New Zealand, 1966. Opposite: Melanesian missionary scholars and cricket players from Norfolk Island with the Bishop of Melanesia, Cecil Wilson, at the home of the Bishop of Christchurch, 1895. -

Contesting Representations of Diasporic Pacific Identities

Between Marginality and Marketability: Contesting Representations of Diasporic Pacific Identities Paloma Fresno-Calleja, University of the Balearic Islands Abstract This article offers an analysis of recent works by New Zealand-born writers and artists of various Pacific descents. It focuses on their revision of popular and institutional representations of the diasporic Pacific community addressing the ambivalent tensions between the marginal and the marketable, which have dominated these representations in the last decades. On the one hand, these works condemn stereotypes of Pacific peoples as a burden to the New Zealand economy and a marginalised minority of inefficient, lazy or dependent people. On the other, they address more recent and complex representations of their culture as a marketable commodity and an exotic addition to New Zealand culture. Keywords: Pacific literature; Pacific diaspora; New Zealand’s ethnic minorities; representation; ethnic stereotypes Introduction In the last few decades New Zealand society has experimented radical changes due to increasing and more diverse immigration flows arriving in the country from the late 1980s. These demographic and social transformations have resulted in the consolidation of new economic patterns and social relations. This article focuses on how some of these changes have affected the New Zealand Pacific community and how New Zealand-born writers and artists of various Pacific descents have engaged in the revision of popular and institutional representations of the diasporic Pacific -

New Zealand Police: Training for Ethnic Responsiveness (A)

CASE PROGRAM 2007-86.1 New Zealand Police: training for ethnic responsiveness (A) “E tū ki te kei o te waka, kia pakia koe e ngā ngaru o te wā” (“Stand at the stern of the canoe and feel the spray of the future biting at your face”) In September 2006, Superintendent Pieri Munro was appointed District Commander of New Zealand Police's Wellington District. It was an opportunity for him to look back on a 30-year career that had focused on building bridges between police and Māori communities, using training to improve the skills and cultural awareness of officers. Pieri Munro joined the police service at a point when New Zealand Police's relationship with the country's non-European peoples was about to hit rock bottom. In 1975, as Munro went through Police College, police officers conducted dawn raids on Pacific Island households in Auckland to search for illegal overstayers. Three years later, the largest police force ever mobilised in New Zealand was sent to forcibly evict hundreds of Māori who had occupied a site on Auckland harbour for 17 months to protest at the last of their ancestral lands being sold by the Crown. The dawn raids and the breaking up of the Bastion Point land protest were to become notorious episodes in New Zealand’s history. In the coming decades, police attitudes towards race relations changed significantly. In 2004, 20,000 marchers converged on Parliament to protest against proposed legislation that they believed would strip Māori of their customary land rights. This time, the priority for police officers was to ensure the This case was developed by the Australia and New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG). -

The Polynesian Panthers and the Black Power Gang: Surviving Racism and Colonialism in Aotearoa New Zealand

The Polynesian Panthers and The Black Power Gang: Surviving Racism and Colonialism in Aotearoa New Zealand Robbie Shilliam Victoria University of Wellington Te Whare Wānanga o te Ūpoko o te Ika a Māui In Nico Slate and Joe Trotter (eds.), Black Power Beyond Borders (Palgrave, forthcoming 2013) Introduction1 Scholars of Black Power are increasingly exploring its global dimensions.2 A number of studies have paid attention to the international connections and influences of key US Black Power people and organizations, 3 and the mapping of the influence of US Black Power across the American and African continents is well underway.4 However, further analysis of the global import, influence and effect of Black Power across the postcolonial world must pay more attention to the various ways in which its postcolonies have been inserted into global hierarchies of colonial and racial orders. In this respect, attention must also be paid to the particular lived experiences of the protagonists who have in various ways heard and interpreted the call to Black Power. This sensitivity is especially important when accounting for the influence of Black Power on colonized and/or oppressed groups that do not directly share an African heritage5. 1 My gratitude to Joe Trotter and Nico Slate for including me in this wonderful project. My thanks to Erina Okeroa for her instructive comments on a draft. And special thanks to Miriama Rauhihi-Ness, Melani Anae, Will ‘Ilolahia, Tigilau Ness, Alec Toleafoa, Dennis O’Reilly and Eugene Ryder for their stories and analyses. Tēnā koutou katoa. Fa'afetai tele lava. Malo 'aupito. -

A Pacific Perspective on the Living Standards Framework and Wellbeing

A Pacific Perspective on the Living Standards Framework and Wellbeing Su’a Thomsen, Jez Tavita and Zsontell Levi-Teu New Zealand Treasury Discussion Paper 18/09 August 2018 DISCLAIMER This paper is part of a series of discussion papers on wellbeing in the Treasury’s Living Standards Framework. The discussion papers are not the Treasury’s position on measuring intergenerational wellbeing and its sustainability in New Zealand. Our intention is to encourage discussion on these topics. There are marked differences in perspective between the papers that reflect differences in the subject matter as well as differences in the state of knowledge. The Treasury very much welcomes comments on these papers to help inform our ongoing development of the Living Standards Framework. NZ TREASURY A Pacific Perspective on the Living Standards Framework and DISCUSSION PAPER 18/09 Wellbeing MONTH/YEAR August 2018 AUTHORS Su’a Thomsen Principal Advisor, Pacific Island Capability The Treasury Jez Tavita Office of the Chief Economic Adviser The Treasury ISBN (ONLINE) 978-1-98-855663-5 URL The Treasury website at August 2018: https://treasury.govt.nz/publications/dp/dp-18-09 NZ TREASURY New Zealand Treasury PO Box 3724 Wellington 6008 NEW ZEALAND Email [email protected] Telephone +64-4-472 2733 Website www.treasury.govt.nz Executive summary The Treasury has been working towards higher living standards for all New Zealanders. Over recent years, the Treasury has developed a Living Standards Framework (LSF) to assess the impact of government policies on current and long-term wellbeing. This framework takes into account the reporting requirements that the Treasury is obligated to deliver to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). -

The Tuvalu Community in Auckland a Focus on Health and Migration

The Tuvalu Community in Auckland A focus on health and migration Sagaa Malua “Transnational Pacific Health through the Lens of Tuberculosis” Research Group Report No. 4 Anthropology, School of Social Sciences, the University of Auckland 2014 Publishing information A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand: http://natlib.govt.nz/ ISBN 978-0-9941013-1-0 Published by ‘The Transnational Pacific Health through the Lens of Tuberculosis’ Research Group, Anthropology, School of Social Sciences, the University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, Auckland 1142, New Zealand. January, 2014 URL http://www.arts.auckland.ac.nz/en/about/schools-in-the-faculty-of-arts/school-of- social-sciences/anthropology/staff-research/social-research-on-tb-and-health.html Table of Contents Glossary of Tuvaluan Words iii Acronyms iii Introduction 1 1.0 Tuvalu 3 2.0 Migration to New Zealand 8 2.1 South Pacific Work Permit Scheme 9 2.2 The Pacific Access Category (PAC) Scheme 9 2.3 Recognised Seasonal Employer (RSE) Scheme 10 2.4 Skilled Migrant and Business Stream 11 2.5 Family-Sponsored Immigration Stream 12 2.6 Section 35A of the Immigration Act 1987, Section 61 of the 2009 Act, and the International/Humanitarian Stream 12 2.6.1 Transitional Policy 2000 13 2.6.2. Refugee Category 13 3.0. The Tuvaluan Community in New Zealand 15 3.1 Background Information on Tuvaluans in Auckland: Kinship, Gender, Work, and Demographics 15 3.2 The Tuvalu Community Trust and Tuvalu Society Incorporated 16 3.3 Island Organisations 19 3.4 Churches