Appendix Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Informationstation.Org Kitchen Table Economics

INFORMATIONSTATION.ORG KITCHEN TABLE ECONOMICS First Job Fridays: Lloyd Blankfein Posted on December 18, 2015 https://informationstation.org/kitchen_table_econ/first-job-fridays-lloyd-blankfein/ When people say “Wall Street,” we im- public housing project in Brooklyn. But he recognizes a deeper importance: mediately think power and wealth. But From an early age, there were two “[You] also know what people go many of New York’s top money-movers things on Blankfein’s mind: His favorite through in the world who don’t grow weren’t born with it—they spent early baseball team, the New York Yankees, out of that, but that’s what they do for mornings and late nights working and the best way to make a living. This a living.” their way up the corporate ladder. A led the young baseball fan to the old life of luxury was something these Yankee Stadium, where he found a job Now leading one of America’s most executives earned on their own, rather as a concession vendor. recognizable investment banks, Blank- than inherited. fein applies that steady sense of humili- Selling soft drinks and peanuts in “the ty to his corporate life, “I need my boss- In our regular First Job Friday feature upper decks” was his first major respon- es’ goodwill, but I need the goodwill of on Information Station, we profile sibility, and Blankfein realized he had to my subordinates even more.” Those who American business leaders whose first take it seriously—the job was “all com- know him best praise his modesty and step on the ladder was anything but mission-based,” meaning no guarantee self-deprecating humor, an approach- “Wall Street.” of personal income. -

01 Leading a Business in a Socially Connected World

01 Leading a business in a socially connected world COPYRIGHT MATERIAL iven this book is aimed at you, the leader, I wanted to start off by Gfocusing directlyNOT FOR on what REPRODUCTION being a leader in a socially connected world means for you. This chapter aims to provide you with insights on where social media for you as a leader fits in, why it matters and the impact that ‘being social’ can have. In fact, before we start, here’s my list of some of the clear benefits. Social media: ●● enables you to tune in and listen in ‘real time’ to your customers, your employees and what’s happening in your sector; ●● enables you to share your viewpoint, in an authentic and conver- sational way; ●● enables you to defend, speak up and mitigate misconceptions; ●● enables you to share your values and your brand’s values. As we go through the book, you’ll hear what other leaders feel are the benefits of being on social media channels – and I’ll endeavour to demonstrate all of the above with real-world examples. My viewpoint and, therefore, the stance in this book, considers that social media, as well as offering you highly practical channels to assist you with driving your business, reaches way beyond the practical application of ‘being social on social networks’ – and rather is enmeshed within the range of technologies that are fast becoming ‘social’ business as usual. M02_CARVILL_K_2558_01_C01.indd 7 1/26/2018 5:18:37 PM 8 Get Social Whilst the focus of this book is to enable you to develop your own social media strategy and tactics, it would be a disservice not to discuss the breadth and depth of social technologies, to equip you with enough compelling context to motivate you to take action and build social media strategies, tactics and activity into your already busy life. -

How Goldman Sachs Turned the Great Recession Into Competitive Advantage Using Strategic Management

How Goldman Sachs Turned the Great Recession into Competitive Advantage Using Strategic Management Mine Doyran The City University of New York Abstract What are the strategic questions confronting Goldman Sachs in the wake of the Great Recession? Goldman Sachs has been considered the most prestigious investment banking firm on Wall Street. Since September 2008, Goldman operates as a bank holding company and financial holding company regulated by the Federal Reserve. It gives advice on how to achieve long-term financial goals in times of both prosperity and crisis. This case reveals how Goldman Sachs became the quintessential global firm for the current period, which combines both growth and weaknesses. It further argues that Goldman Sachs has adopted innovative strategies one step ahead of its competitors, thus surviving the worst of times and redefining the traditional investment banking field. Background Founded in 1869, Goldman Sachs has been considered the most prestigious investment banking firm on Wall Street. Its clients include both public and private institutions seeking funding for expansion to meet the needs of their clients and advice on how to achieve long-term financial goals in times of both prosperity and crisis. Indeed, Goldman would be the quintessential firm for the current period, which combines both growth and weakness. Currently, Goldman Sachs operates as bank holding company and a financial holding company. It is regulated by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. It has an American depository institution subsidiary, Goldman Sachs Bank USA, which is a “New York State-chartered bank.”1 The business of investment firm includes help in planning corporate mergers, Rutgers Business Review Vol. -

Letter to Mr. Lloyd Blankfein, the Goldman Sachs Group

December 19, 2017 Mr. Lloyd Blankfein Chairman and Chief Executive Officer The Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. 200 West Street New York, New York 10282 Dear Mr. Blankfein: On July 1, 2017, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (Board) and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) (together, the Agencies) received the annual resolution plan submission (2017 Plan) of The Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. (GS) required by section 165(d) of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act), 12 U.S.C. § 5365(d), and the jointly issued implementing regulation, 12 CFR Part 243 and 12 CFR Part 381 (the Resolution Plan Rule). The Agencies have reviewed the 2017 Plan taking into consideration section 165(d) of the Dodd-Frank Act, the Resolution Plan Rule, the letter that the Agencies provided to GS on April 12, 2016 (the 2016 Letter) regarding GS’s 2015 resolution plan submission (2015 Plan), the joint “Guidance for 2017 Resolution Plan Submissions By Domestic Covered Companies that Submitted Resolution Plans in July 2015” (the 2017 Plan Guidance), other guidance provided by the Agencies and supervisory information available to the Agencies. 1 In reviewing the 2017 Plan, the Agencies noted meaningful improvements over prior resolution plan submissions of GS. Among other things, the Agencies reviewed the 2017 Plan with respect to the shortcomings in GS’s 2015 Plan. Based upon their review of the 2017 Plan, the Agencies have jointly decided that the 2017 Plan satisfactorily addressed these shortcomings, as discussed in section I, below. Nonetheless, the Agencies have identified one shortcoming in the 2017 Plan, as discussed in section II, below. -

06 LIBOR Materials

LIBOR Item ID: 65 From: Lee, Timothy </O=EXCHANGELABS/OU=EXCHANGE ADMINISTRATIVE GROUP (FYDIBOHF23SPDLT)/CN=RECIPIENTS/CN=D9770D766B6642C4AC0F9F116D0B180D- TIMOTHY LEE> To: (b) (6) Subject: LIBOR Sent: June 29, 2012 8:16 AM Received: June 29, 2012 8:16 AM What do you think the odds are that Bob Diamond is filing for unemployment by Labor Day? ----- Timothy Lee Senior Policy Advisor 202-730-2821 [email protected] RE: LIBOR Item ID: 29 From: (b) (6) To: Lee, Timothy <[email protected]> Subject: RE: LIBOR Sent: June 29, 2012 10:28 AM Received: June 29, 2012 10:29 AM 50-50 From: Lee, Timothy [mailto:[email protected]] Sent: Friday, June 29, 2012 8:17 AM To: (b) (6) (b) (6) Subject: LIBOR What do you think the odds are that Bob Diamond is filing for unemployment by Labor Day? ----- Timothy Lee Senior Policy Advisor 202-730-2821 [email protected] Confidentiality Notice: The information in this email and any attachments may be confidential or privileged under applicable law, or otherwise protected from disclosure to anyone other than the intended recipient(s). Any use, distribution, or copying of this email, including any of its contents or attachments by any person other than the intended recipient, or for any purpose other than its intended use, is strictly prohibited. If you believe you received this email in error, please permanently delete it and any attachments, and do not save, copy, disclose, or rely on any part of the information. Please call the OIG at 202-730-4949 if you have any questions or to let us know you received this email in error. -

Your Basement Gym Is No Match for These $10 Million Wellness Amenities by Cheryl Wischhover

September 23, 2016 Your Basement Gym Is No Match for These $10 Million Wellness Amenities By Cheryl Wischhover Photo: TriggerPhoto/Getty Images/iStockphoto These days, people aren’t above paying $40 several times a week to ride a stationary bike to nowhere, followed by another $8 to cool down with a watermelon juice. In this context, it makes sense that real-estate developers have started adding so-called wellness amenities to new buildings. The days of putting an elliptical machine and some rusty weights in a basement room and calling it a residential gym are long gone. Home buyers in New York City and beyond are settling for nothing less than 10,000-square- foot gyms with pools, hydrothermic regeneration areas, and rooftop meditation rooms. Fredrik Eklund, a NYC-based broker at Douglas Elliman and a star of the real- estate reality show Million Dollar Listing (a.k.a. the only reality show worth watching), says, “Before, wellness was a bonus. You picked a location and you got a great doorman, and on the side you had a gym or a pool. Now people’s lives center around health and wellness.” He credits Jay Wright, who designed the fitness center at 15 Central Park West (the “most powerful” building in NYC, home to Sting and Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein), for starting the over-the-top wellness amenity arms race in buildings. The 14,000-square-foot fitness center there, which includes a 75- foot pool, two steam rooms, and spa treatment rooms, was a standout when apartments hit the market in 2008. -

Goldman Courts the Rich

GOLDMAN’S fortune hunters The securities firm that Wall Street envies ranks just 12th in private banking. CEO Lloyd Blankfein wants to change that. Among the tactics: luring young multimillionaires to Bermuda for beachside classes in hedge fund basics. By ANTHONY EFFINGER he conference started with a cookout at the Mandarin Ori- 17 percent to $13.1 trillion in the same period. ental hotel on Elbow Beach in Bermuda and ended with a With U.S. housing in retreat, global stock and bond talk by 23-year-old Lauren Bush, an antihunger activist, markets shuddering and competitors taking sub- former model and niece to President George W. Bush. In prime-related writedowns, catering to the rich can between, executives at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. taught offer a measure of stability and steady profit. scions of wealthy families how to invest in hedge funds. “Rich people as a business model are sensation- Last October’s “Next Generation” gathering was a small prod in Goldman al,” says Russ Prince, president of Prince & Associ- TSachs’s push into the lucrative profession of private banking. It’s an area of ates Inc., a Redding, Connecticut–based consul- finance that New York–based Goldman—the world’s largest securities firm by tant on financial services for the wealthy. “They’re revenue and profit—doesn’t dominate. Instead, Swiss and U.S. banks reign. willing to pay to make it easy on themselves. They Ranked in assets held by clients with at least $1 million to invest, Goldman don’t fight over fees if they see value.” comes in at No. -

The 100 Most Powerful People in New York Real Estate

NEW YORK, THE REAL ESTATE Jerry Speyer Michael Bloomberg Stephen Ross Marc Holliday Amanda Burden Craig New- mark Lloyd Blankfein Bruce Ratner Douglas Durst Lee Bollinger Michael Alfano James Dimon David Paterson Mort Zuckerman Edward Egan Christine Quinn Arthur Zecken- dorf Miki Naftali Sheldon Solow Josef Ackermann Daniel Boyle Sheldon Silver Steve Roth Danny Meyer Dolly Lenz Robert De Niro Howard Rubinstein Leonard Litwin Robert LiMandri Howard Lorber Steven Spinola Gary Barnett Bill Rudin Ben Bernanke Dar- cy Stacom Stephen Siegel Pam Liebman Donald Trump Billy Macklowe Shaun Dono- van Tino Hernandez Kent Swig James Cooper Robert Tierney Ian Schrager Lee Sand- er Hall Willkie Dottie Herman Barry Gosin David Jackson Frank Gehry Albert Behler Joseph Moinian Charles Schumer Jonathan Mechanic Larry Silverstein Adrian Benepe Charles Stevenson Jr. Michael Fascitelli Frank Bruni Avi Schick Andre Balazs Marc Jacobs Richard LeFrak Chris Ward Lloyd Goldman Bruce Mosler Robert Ivanhoe Rob Speyer Ed Ott Peter Riguardi Scott Latham Veronica Hackett Robert Futterman Bill Goss Dennis DeQuatro Norman Oder David Childs James Abadie Richard Lipsky Paul del Nunzio Thomas Friedan Jesse Masyr Tom Colicchio Nicolai Ourouso! Marvin Markus Jonathan Miller Andrew Berman Richard Brodsky Lockhart Steele David Levinson Joseph Sitt Joe Chan Melissa Cohn Steve Cuozzo Sam Chang David Yassky Michael Shvo 100The 100 Most Powerful People in New York Real Estate Bloomberg, Trump, Ratner, De Niro, the Guy Behind Craigslist! They’re All Among Our 100 Most Powerful People in New York Real Estate ower. Webster’s Dictionary defines power as booster; No. 15 Edward Egan, the Catholic archbish- Governor David Paterson (No. -

Document Filed by Ilene Richman

No. 20-222 In the Supreme Court of the United States GOLDMAN SACHS GROUP, INC., ET AL., PETITIONERS v. ARKANSAS TEACHER RETIREMENT SYSTEM, ET AL. ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT JOINT APPENDIX (VOLUME 1; PAGES 1-400) KANNON K. SHANMUGAM THOMAS C. GOLDSTEIN PAUL, WEISS, RIFKIND, GOLDSTEIN & RUSSELL, P.C. WHARTON & GARRISON LLP 7475 Wisconsin Avenue 2001 K Street, N.W. Suite 850 Washington, DC 20006 Bethesda, MD 20814 (202) 223-7300 (202) 362-0636 [email protected] [email protected] Counsel of Record Counsel of Record for Petitioners for Respondents PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI FILED: AUGUST 21, 2020 CERTIORARI GRANTED: DECEMBER 11, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page VOLUME 1 Court of appeals docket entries (No. 18-3667) ................... 1 Court of appeals docket entries (No. 16-250) ..................... 5 District court docket entries (No. 10-3461) ........................ 8 Goldman Sachs 2007 Form 10-K: Conflicts Warning (D. Ct. Dkt. No. 78-6) .................................................... 23 Goldman Sachs 2007 Annual Report: Business Principles (D. Ct. Dkt. No. 143-16) ............................. 30 Financial Times, Markets & Investing, “Goldman’s risk control offers right example of governance,” Dec. 5, 2007 (D. Ct. Dkt. No. 193-20) .......................... 34 Dow Jones Business News, “13 Reasons Bush’s Bailout Won’t Stop Recession,” Dec. 11, 2007 (D. Ct. Dkt. No. 170-24) ................................................ 37 The Wall Street Journal, “How Goldman Won Big on Mortgage Meltdown,” Dec. 14, 2007 (front page) (D. Ct. Hearing Ex. T) ....................................... 42 The New York Times, Off the Shelf, “Economy’s Loss Was One Man’s Gain,” Dec. -

Goldman Sachs' 1MDB

SPECIAL REPORT APRIL 25, 2019 Goldman Sachs’ 1MDB “Four Monkeys” Defense and CEO Solomon’s Golden Opportunity DAVID SOLOMON LLOYD BLANKFEIN GARY COHN Goldman Sachs’ Chairman & CEO Goldman Sachs’ Former Chairman & CEO Goldman Sachs’ Former President & COO SEE NO HEAR NO SPEAK NO KEEP ALL EVIL EVIL EVIL THE MONEY! Goldman’s “Four Monkeys” Defense Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................... 3 Goldman’s $6.5 Billion Role in Looting 1MDB and Reelecting a Corrupt Prime Minister ........................................................... 5 Goldman’s Partners Are Criminally Charged for Looting $4+ Billion from 1MDB .......................................................................... 6 Goldman’s “Four Monkeys” and Rogue Defenses ....................... 8 The Rogue is Goldman ......................................................... 11 The Road Ahead for Goldman: Criminal and Financial Liability.. 16 CEO Solomon’s Golden Opportunity: The Choice of True Leadership or More of the Same ............................................................. 18 Citations ............................................................................ 21 INTRODUCTION 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) was a Malaysian government owned and controlled investment fund created in 2009 by former Prime Minister Najib Razak. The professed purpose of 1MDB was to attract foreign investment and development in Malaysia to benefit all the people of Malaysia. Instead, it has been referred to as “kleptocracy at -

A Brief History of Goldman Sachs

A Brief History of Goldman Sachs Established 1869 In 1869, a German immigrant named Marcus Goldman moved to New York City with his family and opened a one-room basement office next to a coal chute at 30 Pine Street in Lower Manhattan. During a period of tight and expensive bank credit, Goldman offered the local merchants an alternative. He would purchase their promissory notes and then sell the notes to New York’s commercial banks, becoming a pioneer in what became known as the commercial paper business. With the addition of his son-in-law, Samuel Sachs, in 1882, and his son, Henry Goldman, in 1885, Marcus Goldman’s enterprise became a partnership with a new name: Goldman, Sachs & Co. By the time the firm joined the New York Stock Exchange in 1896, Goldman Sachs was a leader in commercial paper sales. As the firm’s clients grew in number, it opened offices in Boston and Chicago (1900), San Francisco (1918), and Philadelphia and St. Louis (1920), becoming a national firm. In 1897, Goldman Sachs established relationships with financial firms in major European capitals, providing an array of services that included foreign exchange, letters of credit, gold shipments and arbitrage. In the early 1900s, as clients increasingly needed larger amounts of long-term capital, the firm began to establish its investment banking business. In two of the firm’s first public transactions— initial stock offerings for General Cigar and Sears Roebuck, both in 1906—Goldman Sachs broke new ground in making equity and debt securities more attractive to investors. -

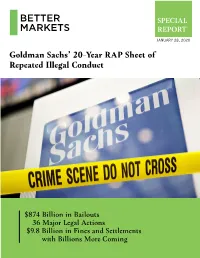

Goldman Sachs' 20-Year RAP Sheet of Repeated Illegal Conduct

SPECIAL REPORT JANUARY 28, 2020 Goldman Sachs’ 20-Year RAP Sheet of Repeated Illegal Conduct $874 Billion in Bailouts 36 Major Legal Actions $9.8 Billion in Fines and Settlements with Billions More Coming INTRODUCTION This Report details Goldman Sachs’ RAP sheet of illegal behavior over more than two decades. It is shocking in its depth and breadth. It reveals wide-ranging, predatory, recidivist lawbreaking from 1998 through 2019. Because it is still pending, this Report does not include Goldman’s liability for the sprawling global criminal and other illegal activities related to the 1MDB scandal (which were detailed in a prior Report here). This Report also details how Goldman Sachs was saved from bankruptcy and bailed out by the U.S. government during the 2008 financial crash, which Goldman Sachs’ own conduct caused or contributed to significantly according to many reports. The bottom line: Goldman Sachs has committed dozens of illegal acts and preyed upon and ripped off countless Main Street Americans with a frequency and severity that shocks the conscience. In fact, in the last two decades, while receiving more than $874 billion in bailouts, Goldman Sachs has been subject to 36 major legal actions that have resulted in over $9.8 billion in fines and settlements. Those facts demonstrate that Goldman Sachs is a too-big-to-fail, too-big-to-jail, too-big-to-regulate and too-big-to-manage Wall Street bank. As Goldman Sachs holds its first investor day on Wednesday, January 29, 2020, investors and others should look not only at Goldman’s presentation of its strategic priorities, but also at its history of illegal activities.