Priyanka Dutta* Abstract Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

W.B.C.S.(Exe.) Officers of West Bengal Cadre

W.B.C.S.(EXE.) OFFICERS OF WEST BENGAL CADRE Sl Name/Idcode Batch Present Posting Posting Address Mobile/Email No. 1 ARUN KUMAR 1985 COMPULSORY WAITING NABANNA ,SARAT CHATTERJEE 9432877230 SINGH PERSONNEL AND ROAD ,SHIBPUR, (CS1985028 ) ADMINISTRATIVE REFORMS & HOWRAH-711102 Dob- 14-01-1962 E-GOVERNANCE DEPTT. 2 SUVENDU GHOSH 1990 ADDITIONAL DIRECTOR B 18/204, A-B CONNECTOR, +918902267252 (CS1990027 ) B.R.A.I.P.R.D. (TRAINING) KALYANI ,NADIA, WEST suvendughoshsiprd Dob- 21-06-1960 BENGAL 741251 ,PHONE:033 2582 @gmail.com 8161 3 NAMITA ROY 1990 JT. SECY & EX. OFFICIO NABANNA ,14TH FLOOR, 325, +919433746563 MALLICK DIRECTOR SARAT CHATTERJEE (CS1990036 ) INFORMATION & CULTURAL ROAD,HOWRAH-711102 Dob- 28-09-1961 AFFAIRS DEPTT. ,PHONE:2214- 5555,2214-3101 4 MD. ABDUL GANI 1991 SPECIAL SECRETARY MAYUKH BHAVAN, 4TH FLOOR, +919836041082 (CS1991051 ) SUNDARBAN AFFAIRS DEPTT. BIDHANNAGAR, mdabdulgani61@gm Dob- 08-02-1961 KOLKATA-700091 ,PHONE: ail.com 033-2337-3544 5 PARTHA SARATHI 1991 ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER COURT BUILDING, MATHER 9434212636 BANERJEE BURDWAN DIVISION DHAR, GHATAKPARA, (CS1991054 ) CHINSURAH TALUK, HOOGHLY, Dob- 12-01-1964 ,WEST BENGAL 712101 ,PHONE: 033 2680 2170 6 ABHIJIT 1991 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR SHILPA BHAWAN,28,3, PODDAR 9874047447 MUKHOPADHYAY WBSIDC COURT, TIRETTI, KOLKATA, ontaranga.abhijit@g (CS1991058 ) WEST BENGAL 700012 mail.com Dob- 24-12-1963 7 SUJAY SARKAR 1991 DIRECTOR (HR) BIDYUT UNNAYAN BHAVAN 9434961715 (CS1991059 ) WBSEDCL ,3/C BLOCK -LA SECTOR III sujay_piyal@rediff Dob- 22-12-1968 ,SALT LAKE CITY KOL-98, PH- mail.com 23591917 8 LALITA 1991 SECRETARY KHADYA BHAWAN COMPLEX 9433273656 AGARWALA WEST BENGAL INFORMATION ,11A, MIRZA GHALIB ST. agarwalalalita@gma (CS1991060 ) COMMISSION JANBAZAR, TALTALA, il.com Dob- 10-10-1967 KOLKATA-700135 9 MD. -

WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTION COMMISSION 18, SAROJINI NAIDU SARANI (Rawdon Street) KOLKATA – 700 017 Ph No.2280-5277 ; FAX: 2

WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTION COMMISSION 18, SAROJINI NAIDU SARANI (Rawdon Street) – KOLKATA 700 017 Ph No.2280-5277 ; FAX: 2280-7373 No. 1809-SEC/1D-131/2012 Kolkata, the 3rd December 2012 In exercise of the power conferred by Sections 16 and 17 of the West Bengal Panchayat Elections Act, 2003 (West Bengal Act XXI of 2003), read with rules 26 and 27 of the West Bengal Panchayat Elections Rules, 2006, West Bengal State Election Commission, hereby publish the draft Order for delimitation of Malda Zilla Parishad constituencies and reservation of seats thereto. The Block(s) have been specified in column (1) of the Schedule below (hereinafter referred to as the said Schedule), the number of members to be elected to the Zilla Parishad specified in the corresponding entries in column (2), to divide the area of the Block into constituencies specified in the corresponding entries in column (3),to determine the constituency or constituencies reserved for the Scheduled Tribes (ST), Scheduled Castes (SC) or the Backward Classes (BC) specified in the corresponding entries in column (4) and the constituency or constituencies reserved for women specified in the corresponding entries in column (5) of the said schedule. The draft will be taken up for consideration by the State Election Commissioner after fifteen days from this day and any objection or suggestion with respect thereto, which may be received by the Commission within the said period, shall be duly considered. THE SCHEDULE Malda Zilla Parishad Malda District Name of Block Number of Number, Name and area of the Constituen Constituen members to be Constituency cies cies elected to the reserved reserved Zilla Parishad for for ST/SC/BC Women persons (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) Bamongola 2 Bamongola/ZP-1 SC Women Madnabati, Gobindapur- Maheshpur and Bamongola grams Bamongola/ZP-2 SC Chandpur, Pakuahat and Jagdala grams HaHbaibipbupru/rZ P- 3 Women 3 Habibpur/ZP-4 ST Women Mangalpura , Jajoil, Kanturka, Dhumpur and Aktail and Habibpur grams. -

Ambulance List.Xlsx

Data regarding Ambulances under Malda District as on 18-03-2020 S. No Registration No. Owner's Name Current Address Mobile No. Name of Driver Contact No VILL-NEW PATALDANGA,PO-MOTHABARI,PS- WB11B2840 RABIUL ISLAM 9735018336 ROBIUL ISLAM 8348060618 1 MOTHABARI,Maldah ,West Bengal,732207 UTTAR WB37B7950 SUROJIT SIL S DARIAPUR,KALIACHAK,MALDA,Maldah ,West 9733419417 MAMUN SK 9593578103 2 Bengal,732201 KRISHNAPALLY,ENGLISH WB53B3385 AMIT CHOWDHURY 9735068349 SANJIB 8158068120 3 BAZAR,MALDA,Maldah ,West Bengal,732101 KRISHNAPALLY,MALDA,ENGLISH WB57A1939 ASIM CHOUDHURI 9456451321 MOHON 6295298967 4 BAZAR,Maldah ,West Bengal,732101 LAKRIPUR,PO- HATIMARI,PS- WB656752 BABULAL MARDI 9002918157 Self Self 5 GAZOLE,Maldah ,West Bengal,732127 VILL--MANGALBARI,SCHOOL PARA,DIST-- WB658882 SAJAL KR DAS 9434680422 TARAK GHOSH 8597136319 6 MALDA,,West Bengal,999999 TULSIDANGA,GAZOLE,MALDA,,West WB659172 MOJAMMAL HOQUE 9800755654 Self Self 7 Bengal,999999 MD. NURE ALAM CHANDIGACHHI, SINGIA,CHANCHAL,DIST- WB659298 9734163372 Self Self 8 SARKAR MALDA (W.B.),,West Bengal,732123 VILL NABA KRISHNAPALLY,PS. ENGLISH WB659319 PRAKASH SARKAR BAZAR,PO. + DIST. MALDA, WB,,West 9434680422 SUMIT KISKU 8509410536 9 Bengal,732101 VILL- SUSHMA TRIPATHY,MEMORIAL WB659525 MADHUMITA TRIPATHY NURSING HOME,JHALJHALIA, DIST- 9932931538 MAHABIR DEB 8001671888 10 MALDA,,West Bengal,111111 VILL-NABA KRISHNAPALLY,P.S-ENGLISH WB65A0810 PRAKASH SARKAR 9434680422 DIPAK ROY 8001525520 11 BAZAR,DIST-MALDA,,West Bengal,999999 MAHAJANTOLA,BAISHNABNAGAR,BAISHNAB WB65A0841 SWAPAN SINHGHA 9734992676 ROMESH MONDAL 9932057489 12 NAGAR,Maldah ,West Bengal,732127 MR KESHAB CHANDRA VILL. & P.O. CHOWKI,P.S. MANIKCHAK,DIST. WB65A1080 9434256150 Self Self 13 MISHRA MALDA,,West Bengal,999999 SECRETARY R K R.K. -

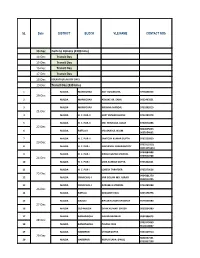

SL Date DISTRICT BLOCK VLE NAME CONTACT NOS 13

SL Date DISTRICT BLOCK VLE NAME CONTACT NOS 13-Dec Delhi to Kolkata (1500 kms) 14-Dec Transit Day 15-Dec Transit Day 16-Dec Transit Day 17-Dec Transit Day 18-Dec KOLKATA (FLAG OFF DAY) 19-Dec Transit Day (330 kms) 1 MALDA MANIKCHAK ASIT KUMAR JHA 9775838353 20-Dec 2 MALDA MANIKCHAK ASHOKE KR. SAHA 9932497851 3 MALDA MANIKCHAK KRISHNA MANDAL 9733392019 21-Dec 4 MALDA H. C. PUR-II SUJIT KUMAR GHOSH 9733380378 5 MALDA H. C. PUR-II MD. MINHAJUL ALAM 9734974498 22-Dec 9800825623 6 MALDA RATUA-II MD.ANARUL ISLAM 9635954002 7 MALDA H. C. PUR-II SANTOSH KUMAR GUPTA 9733225820 23-Dec 9733113110, 8 MALDA H. C. PUR-I NABYENDU CHAKRABORTY 03513255610 9434684698 9 MALDA H. C. PUR-I RINKU KUMAR MANDAL 9749920708 24-Dec 10 MALDA H. C. PUR-I UMA SANKAR GUPTA 9733202661 11 MALDA H. C. PUR-I LOKESH TARAFDER 9733279636 25-Dec 9434381279 12 MALDA CHANCHAL-I MIR GOLAM MD. ASRAFI 9932014705 13 MALDA CHANCHAL-I AKRAMUL MANDAL 9733280384 26-Dec 14 MALDA RATUA-I DEBASISH PAUL 9233178778 15 MALDA GAZOLE BIPLAB KUMAR UPADHAY 9475956980 27-Dec 16 MALDA OLD MALDA DIPAK KUMAR GHOSH 9932834380 17 MALDA BAMANGOLA NAYAN BARMAN 9932396075 28-Dec 9733310460 18 MALDA BAMANGOLA PALASH DAS 9614618807 19 MALDA HABIBPUR UTTAM GUPTA 9434129914 29-Dec 9851037441 20 MALDA HABIBPUR NUPUR SAHA (PAUL) 8759357208 21 MALDA HABIBPUR AKALU HALDER 9800816802 30-Dec 9434421774, 22 MALDA HABIBPUR SUDESHNA SAHA 03511-253636 23 MALDA OLD MALDA SUROJIT SAHA 9932167734 31-Dec 24 MALDA ENGLISH BAZAR SOMNATH MONDAL 9002034035 25 MALDA ENGLISH BAZAR MD. -

Volunteer Name with Reg No State (District) (Block) Mobile No APSANA KHATUN (61467) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Fanside

Volunteer Name with Reg No State (District) (Block) Mobile no APSANA KHATUN (61467) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Fansidewa) 9547651060 RABINA KHAWAS (64657) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Kalimpong-I) 7586094862 NITSHEN TAMANG (64650) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Takda) 9564994554 ARBIND SUBBA (61475) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Takda) 7001894077 SANTOSH KUMAR PASWAN (61593) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Nakshalbari) 8917830020 SAMIRAN KHATUN (64837) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Fansidewa) 7407206018 ANISHA THAKURI (64645) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Bijanbari) 7679456517 BIKASH SINGHA (61913) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Kharibari) 9064394568 PUSKAR TAMANG (64607) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Garubathan) 8436112429 ANIP RAI (61968) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Bijanbari) 7047337757 SUDIBYA RAI (61976) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Kalimpong-II) 8944824498 DICHEN LAMA (64633) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Kalimpong-II) 9083860892 YOGESH N SARKI (62019) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Kurseong) 7478305517 BIJAYA LAXMI SINGH (61586) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Matigara) 9932839481 SAGAR RAI (64619) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Garubathan) 7029143177 DEEPTI BISWAKARMA (61491) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Garubathan) 9734902283 ANMOL CHHETRI (61496) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Kurseong) 9593951858 BIJAY CHANDRA SHARMA (61470) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Kalimpong-I) 9233666950 KHAGESH ROY (61579) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Nakshalbari) 8759721171 SANGAM SUBBA (61462) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Mirik) 8972908640 LIMESH TAMANG (64627) WEST BENGAL (Darjiling) (Bijanbari) 9679167713 ANUSHILA LAMA TAMANG (61452) WEST BENGAL -

Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Tuberculosis in Malda District, West Bengal

Tapan Pramanick et al, IJSRR 2019, 8(2), 3022-3038 Research article Available online www.ijsrr.org ISSN: 2279–0543 International Journal of Scientific Research and Reviews Spatio-temporal analysis of Tuberculosis in Malda District, West Bengal Tapan Pramanick1* and N.C. Jana2 1* M.Phil. Research Scholar, Department of Geography, The University of Burdwan, Burdwan- 713104, West Bengal, India. Email: [email protected], Mobile-9732299065 2 Professor, Department of Geography, The University of Burdwan, Burdwan-713104, West Bengal, India. Email: [email protected], Mobile-9593566783 ABSTRACT The present study is an attempt to analyze the spatial variation of Tuberculosis (TB) in Malda district, West Bengal, India. TB has become an emerging challenge for the health planners of the district as well as the state administrators. It may be mentioned in this context that in 2016, 5094 TB patients were notified in Malda district which is one of the high TB burden areas in respect of population compared to another district of West Bengal. TB notification data from 2011 to 2016 have been collected from District Tuberculosis Center (DTC), Malda and Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Spatial Autocorrelation method has been used to analyze the spatial pattern detection of Tuberculosis. ArcGIS and SPSS were used for the analysis of the distribution of tuberculosis and clustering. The findings of this study show that Englishbazar Urban, Habibpur, Kaliachak-I, and Old Malda Rural are the most affected areas of Malda district. On the other hand, Manikchak, Harishchandrapur, Baishnabnagar, and Ratua-II have a lower concentration of TB patients. -

Review of Research Impact Factor : 5.2331(Uif) Ugc Approved Journal No

Review Of ReseaRch impact factOR : 5.2331(Uif) UGc appROved JOURnal nO. 48514 issn: 2249-894X vOlUme - 7 | issUe - 8 | may - 2018 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ THE STUDY OF DEVELOPMENTAL GAPS IN EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM OF MALDA DISTRICT, WEST BENGAL, INDIA Munshi MD Amin Research Scholar, Cooch Behar Panchanan Barma University. ABSTRACT: Education is the dynamic force for the development of the society. Education means reconstruction of society with human power. Education refers to the backbone of society for the social upliftment. A society’s total development depends on appropriate education. Education is the main driving force of the nation. Education shapes a society in the sense of socio-cultural, Demographic, economic, and politically. A countries Quality of life and social wellbeing controlled significantly by the educational development of that place. Educational gap makes the regional disparity of a place which creates imbalance societal development as it brings the equity and equality in the society. The present paper is to show the developmental gaps in the education system of Maldah District, West Bengal. The study has been conducted based on Secondary data collection and used some appropriate statistical techniques. The result has been showed that there is an educational gap in response to the spatial and temporal context in Maldah district, West Bengal. KEY WORDS: - Educational Gap, Educational System, Literacy Rate, Educational Infrastructure, Malda District. INTRODUCTION Education refers to the backbone of every society for their development. It is the key factor for human resource development like skill, knowledge, affection. Regional development more or less depends on the educational system and its status, quality of that place. -

Migration As Source of Risk-Aversion Among the Environmental Refugees

www.ssoar.info Migration as source of risk-aversion among the environmental refugees: the case of women displaced by erosion of the river Ganga in the Malda District of West Bengal Dutta, Priyanka Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Arbeitspapier / working paper Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: SSG Sozialwissenschaften, USB Köln Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Dutta, P. (2011). Migration as source of risk-aversion among the environmental refugees: the case of women displaced by erosion of the river Ganga in the Malda District of West Bengal. (COMCAD Working Papers, 98). Bielefeld: Universität Bielefeld, Fak. für Soziologie, Centre on Migration, Citizenship and Development (COMCAD). https://nbn- resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-398647 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under Deposit Licence (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, non- Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, transferable, individual and limited right to using this document. persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses This document is solely intended for your personal, non- Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für commercial use. All of the copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. -

Rural Hospital 2 Anchuri Rural Hospital * Bankura-I Anchuri 03242 - 254056 30 KFW-GTZ [email protected]

Upgraded Sl. Name of the Institution Block Post Office Telephone No. Beds E-mail Id. No. Under Program District : Bankura Sub-Division : Sadar Gangajalghati (Amar Kanan) 1 Gangajalghati Amar Kanan 03241 - 265226 30 [email protected] Rural Hospital 2 Anchuri Rural Hospital * Bankura-I Anchuri 03242 - 254056 30 KFW-GTZ [email protected] 3 Chhatna Rural Hospital * Chhatna Chhatna 03242 - 205497 30 KFW-GTZ [email protected] 4 Saltora Rural Hospital * Saltora Saltora 03241 - 273228 30 KFW-GTZ [email protected] 5 Barjora Rural Hospital * Barjora Barjora 03241 - 257228 30 BHP [email protected] 6 Onda Rural Hospital * Onda Medinipur Gram 03242 - 203113 30 KFW-GTZ [email protected] Sub-Division : Khatra 7 Taldangra Rural Hospital Taldangra Taldangra 03243 - 265234 30 [email protected] 8 Raipur Rural Hospital Raipur I Nutangarh 03243 - 267540 30 [email protected] Amjhuri (Hirbandh) Rural 9 Khatra-II Hirbandh 03243 - 252300 30 BHP [email protected] Hospital * 10 Ranibandh Rural Hospital * Ranibandh Ranibandh 03243 - 250235 30 HSDI [email protected] 11 Simlapal Rural Hospital * Simlapal Simlapal 03243 - 262247 30 NRHM [email protected] 12 Sarenga Rural Hospital * Raipur II Krishnapur 30 HSDI [email protected] 13 Indpur Rural Hospital * Indpur Indpur 03242 - 260221 30 BHP [email protected] Sub-Division : Bishnupur 03244 - 14 Sonamukhi Rural Hospital Sonamukhi Sonamukhi 30 [email protected] 275154/275250 15 Kotalpur Rural Hospital Kotalpur Kotalpur 03244 - 240243 60 [email protected] Hat- 16 Patrasayer Rural Hospital * Patrasayer 03244 - 266239 30 NRHM [email protected] Krishnanagar 17 Indas Rural Hospital * Indas Indas 03244 - 263237 30 NRHM [email protected] Upgraded Sl. -

W.B.C.S.(Exe.) Officers of West Bengal Cadre As on 22-11-2016

W.B.C.S.(EXE.) OFFICERS OF WEST BENGAL CADRE AS ON 22-11-2016 Sl Name/Idcode Batch Present Posting Posting Address Mobile/Email No. 1 AMAR 1985 SPECIAL SECRETARY NABANNA,SARAT CHATTERJEE +919836774352 BHATTACHARYYA P & A. R. ROAD ,SHIBPUR, amarbhattacharyya (CS1985017 ) HOWRAH-711102 @yahoo.com 2 OSMAN GANI 1985 SECRETARY WEST BENGAL STATE +919163143210 (CS1985018 ) STATE ELECTION COMMISSION ELECTION COMMISSION ,18, [email protected] SAROJINI NAIDU SARANI om RAODON ST. ,KOLKATA-700017 3 ARUN KUMAR 1985 COMPULSORY WAITING NABANNA ,SARAT CHATTERJEE SINGH P & A. R. ROAD ,SHIBPUR, (CS1985028 ) HOWRAH-711102 4 JANG BAHADUR 1986 ADDL. DIRECTOR, SMALL BERHAMPORE ,MURSHIDABAD SUBBA SAVINGS (CS1986214 ) MURSHIDABAD 5 DURGA KINKAR 1986 SPECIAL SECRETARY NABANNA ,HRBC BUILDING, +919434333986 MAHAPATRA FINANCE 325, SARAT CHATTERJEE (CS1986215 ) ROAD,MANDIRTALA SHIBPUR, HOWRAH-711102 6 DEBAJYOTI 1986 SECRETARY-CUM- MAYUKH BHABAN, SALT LAKE, BHATTACHARYYA CONTROLLER OF EXAM KOLKATA- 700091 ,PHONE: (CS1986219 ) WBSSC 2337-3556 7 GOPAL CH. GHOSE 1986 SPECIAL SECRETARY NAGARAYAN BHAVAN, BLOCK- +919836673222 (CS1986220 ) URBAN DEVELOPMENT DF-8, SECTOR-I,SALT LAKE [email protected] CITY, KOLKATA, WEST BENGAL m 700064 ,PHONE:033 2334 9336 8 ASIM KUMAR 1986 SPECIAL SECRETARY BIKASH BHAVAN, 5TH AND 6TH BHATTARYYA SCHOOL EDUCATION FLOOR DF BLOCK, SECTOR-1, (CS1986222 ) SALT LAKE CITY, KOLKATA, WEST BENGAL 700091 ,PHONE: 23342256 9 BIDYUT 1986 SPECIAL SECRETARY POURA BHAVAN, 4TH FLOOR, BHATTACHARYA ENVIRONMENT FD-415/A, SECTOR-III, (CS1986224 ) BIDHANNAGAR, KOLKATA-700106. -

Risk Assessment of Arsenic Toxicity Through Ground Water-Soil-Rice System in Maldah District, Bengal Delta Basin, India

Risk Assessment of Arsenic Toxicity Through Ground Water-Soil-Rice System in Maldah District, Bengal Delta Basin, India Rubina Khanam CRRI: Central Rice Research Institute Gora Chand Hazra ( [email protected] ) Bidhan Chandra Krishi Viswavidyalaya: Bidhan Chandra Krishi Viswa Vidyalaya Animesh Gosh Bag Bidhan Chandra Krishi Viswavidyalaya: Bidhan Chandra Krishi Viswa Vidyalaya Nitin Chatterjee Bidhan Chandra Krishi Viswavidyalaya: Bidhan Chandra Krishi Viswa Vidyalaya Pedda Ghouse Peera Sheikh Kulsum C V Raman Global University Arvind Kumar Shukla Indian Institute of Soil Science Research Article Keywords: Arsenic, Rice, Irrigation water, Inceptisols, Spatial Map, Hazard quotient Posted Date: May 17th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-508581/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License 1 Risk assessment of arsenic toxicity through ground water-soil-rice system in Maldah 2 district, Bengal Delta basin, India 3 4 Rubina Khanama, Gora Chand Hazra*b, Animesh Gosh Bagb, Nitin Chatterjeeb, Pedda 5 Ghouse Peera Sheikh Kulsumc, Arvind Kumar Shuklad 6 7 8 aICAR-National Rice Research Institute, Cuttack, Odisha-753006, India 9 bBidhan Chandra Krishi Viswavidyalaya, Mohanpur- 741252, West Bengal, India 10 cC V Raman Global University, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India 11 dICAR-Indian Institute of Soil Science, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India 12 13 14 15 *Corresponding author: Department of Agricultural Chemistry and Soil Science, Bidhan 16 Chandra Krishi Viswavidyalaya, Mohanpur- 741252, West Bengal, India, 17 [email protected] 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 1 34 Abstract: 35 Arsenic (As), a toxic trace element, is of great environmental concern due to its presence in 36 soil, water, plant, animal and human continuum. -

PC Wise Polling Station and Electors

PC and AC Wise Polling Station and Elector Elector as on the last date of nomination Total No. of Phase PC NO PC NAME District No. & Name AC No. & NAME Third Polling Station Male Female Total Gender 2 Mathabhanga 270 125634 115800 0 241434 3 Cooch Behar Uttar 305 141519 129501 2 271022 Cooch Behar COOCHBEHAR 1 1 COOCHBEHAR 4 Dakshin 255 114846 108178 2 223026 1 (SC) 5 Sitalkuchi 301 144980 130433 2 275415 6 Sitai 293 144763 132195 0 276958 7 Dinhata 316 148584 139382 0 287966 8 Natabari 270 121153 113686 0 234839 1.COOCHBEHAR (SC) Total 2010 941479 869175 6 1810660 1 COOCHBEHAR 9 Tufanganj 252 117172 108378 0 225550 10 Kumargram 298 134350 127423 2 261775 11 Kalchini 264 116886 118077 6 234969 ALIPURDUARS 2 2 ALIPURDUAR 12 Alipurduars 277 126993 122066 5 249064 1 (ST) 13 Falakata 266 124873 119198 2 244073 14 Madarihat 220 100808 101903 5 202716 3 JALPAIGURI 21 Nagrakata 257 110635 114831 3 225469 2. ALIPURDUARS (ST) Total 1834 831717 811876 23 1643616 1 COOCHBEHAR 1 Mekliganj 235 111455 105084 1 216540 15 Dhupguri 260 129038 122159 0 251197 16 Maynaguri 272 129786 120983 0 250769 3 JALPAIGURI (SC) 17 Jalpaiguri 282 128296 126257 2 254555 2 3 JALPAIGURI 18 Rajganj 256 120154 113386 6 233546 19 Dabgram-Fulbari 295 145143 138430 4 283577 20 Mal 268 121581 120064 5 241650 3. JALPAIGURI (SC) Total 1868 885453 846363 18 1731834 4 KALIMPONG 22 Kalimpong 261 101368 102115 2 203485 23 Darjeeling 321 115756 119241 0 234997 24 Kurseong 292 111605 116226 2 227833 Matigara- 5 DARJEELING 4 DARJEELING 307 132962 132772 1 265735 2 25 Naxalbari 26 Siliguri 245 109857 105404 0 215261 27 Phansidewa 248 113940 109669 4 223613 UTTAR 6 DINAJPUR 28 Chopra 225 121630 107998 12 229640 4.