23/Summer 1999

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Labour, Old Morality

New Labour, Old Morality. In The IdeasThat Shaped Post-War Britain (1996), David Marquand suggests that a useful way of mapping the „ebbs and flows in the struggle for moral and intellectual hegemony in post-war Britain‟ is to see them as a dialectic not between Left and Right, nor between individualism and collectivism, but between hedonism and moralism which cuts across party boundaries. As Jeffrey Weeks puts it in his contribution to Blairism and the War of Persuasion (2004): „Whatever its progressive pretensions, the Labour Party has rarely been in the vanguard of sexual reform throughout its hundred-year history. Since its formation at the beginning of the twentieth century the Labour Party has always been an uneasy amalgam of the progressive intelligentsia and a largely morally conservative working class, especially as represented through the trade union movement‟ (68-9). In The Future of Socialism (1956) Anthony Crosland wrote that: 'in the blood of the socialist there should always run a trace of the anarchist and the libertarian, and not to much of the prig or the prude‟. And in 1959 Roy Jenkins, in his book The Labour Case, argued that 'there is a need for the state to do less to restrict personal freedom'. And indeed when Jenkins became Home Secretary in 1965 he put in a train a series of reforms which damned him in they eyes of Labour and Tory traditionalists as one of the chief architects of the 'permissive society': the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality, reform of the abortion and obscenity laws, the abolition of theatre censorship, making it slightly easier to get divorced. -

The Conservative Agenda for Constitutional Reform

UCL DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE The Constitution Unit Department of Political Science UniversityThe Constitution College London Unit 29–30 Tavistock Square London WC1H 9QU phone: 020 7679 4977 fax: 020 7679 4978 The Conservative email: [email protected] www.ucl.ac.uk/constitution-unit A genda for Constitutional The Constitution Unit at UCL is the UK’s foremost independent research body on constitutional change. It is part of the UCL School of Public Policy. THE CONSERVATIVE Robert Hazell founded the Constitution Unit in 1995 to do detailed research and planning on constitutional reform in the UK. The Unit has done work on every aspect AGENDA of the UK’s constitutional reform programme: devolution in Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and the English regions, reform of the House of Lords, electoral reform, R parliamentary reform, the new Supreme Court, the conduct of referendums, freedom eform Prof FOR CONSTITUTIONAL of information, the Human Rights Act. The Unit is the only body in the UK to cover the whole of the constitutional reform agenda. REFORM The Unit conducts academic research on current or future policy issues, often in collaboration with other universities and partners from overseas. We organise regular R programmes of seminars and conferences. We do consultancy work for government obert and other public bodies. We act as special advisers to government departments and H parliamentary committees. We work closely with government, parliament and the azell judiciary. All our work has a sharply practical focus, is concise and clearly written, timely and relevant to policy makers and practitioners. The Unit has always been multi disciplinary, with academic researchers drawn mainly from politics and law. -

Schuler Dissertation Final Document

COUNSEL, POLITICAL RHETORIC, AND THE CHRONICLE HISTORY PLAY: REPRESENTING COUNCILIAR RULE, 1588-1603 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Anne-Marie E. Schuler, B.M., M.A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Professor Richard Dutton, Advisor Professor Luke Wilson Professor Alan B. Farmer Professor Jennifer Higginbotham Copyright by Anne-Marie E. Schuler 2011 ABSTRACT This dissertation advances an account of how the genre of the chronicle history play enacts conciliar rule, by reflecting Renaissance models of counsel that predominated in Tudor political theory. As the texts of Renaissance political theorists and pamphleteers demonstrate, writers did not believe that kings and queens ruled by themselves, but that counsel was required to ensure that the monarch ruled virtuously and kept ties to the actual conditions of the people. Yet, within these writings, counsel was not a singular concept, and the work of historians such as John Guy, Patrick Collinson, and Ann McLaren shows that “counsel” referred to numerous paradigms and traditions. These theories of counsel were influenced by a variety of intellectual movements including humanist-classical formulations of monarchy, constitutionalism, and constructions of a “mixed monarchy” or a corporate body politic. Because the rhetoric of counsel was embedded in the language that men and women used to discuss politics, I argue that the plays perform a kind of cultural work, usually reserved for literature, that reflects, heightens, and critiques political life and the issues surrounding conceptions of conciliar rule. -

THE RISE and FALL of NEW YORK MURDER Zero Tolerance Or Crack’S Decline?

BRIT. J. CRIMINOL. VOL. 39 NO. 4 AUTUMN 1999 THE RISE AND FALL OF NEW YORK MURDER Zero Tolerance or Crack’s Decline? BENJAMIN BOWLING* The striking reduction in homicide in New York City between 1991 and 1997 has been claimed as a great success for a ‘new’ policing tactic dubbed ‘zero tolerance’—the aggressive enforcement of minor offences. The evidence that changes in policing made ‘all the difference’ is largely circumstantial, however. Homicide rates were at an all-time high in 1990–91 and had begun to decline before any radical changes in policing policy were instituted. The 1985–91 ‘murder spike’ has been attributed largely to the simultaneous expanding crack cocaine ‘epidemic’ so the subsequent reduction in murder is related logically to the contraction of crack cocaine markets in the 1990s. There is some tentative support for the impact of policing on an already falling crime rate, but the changes in policing between 1991 and 1997 cannot adequately be described as ‘zero tolerance’. The author argues that the ‘New York story’ has been over-simplified and over-sold, and that ‘zero tolerance’ is an inappropriate language for police policy or practice. ‘New York made me do it’ (spray paint graffiti, anonymous, New Cross, London) On 6 January 1997, Tony Blair, then Prime Minister-in-Waiting, was asked whether he agreed with ‘so called Zero-Tolerance policies—practised in New York and being experimented with in London’s King’s Cross—in which every minor law is clamped down on hard by police’. His affirmative answer, ‘Yes I do’, married New Labour to zero tolerance.1 The romance between the Labour party and ‘New York-style policing’ began in the summer of 1995 when shadow Home Secretary Jack Straw visited New York to meet police Commissioner William Bratton and his deputy Jack Maple. -

TV Invited to Put EU in Spotlight After Britain Drops Opposition

TV invited to put EU in spotlight after Britain drops opposition By Stephen Castle and Andrew Grice in Brussels The Independent 17 June 2006 A British volte-face over openness in the EU has ended in humiliation as Tony Blair failed to water down moves to throw open law-making sessions to TV cameras and public scrutiny. At a summit in Brussels yesterday EU leaders agreed to plans, originally put forward in the European constitution, to make public all debates and votes by ministers on mainstream European legislation. Britain put forward very similar proposals last year during its six-month presidency of the EU when it called for the beginning and end of the procedures to be held in public. But when Austria, which now holds the presidency, proposed opening up all the process, the new Foreign Secretary, Margaret Beckett, came out against the plan. Arguing that this would push real decision-making into the corridors, she insisted that detailed discussions are, "not in the public domain and are never likely to be". Yesterday Mr Blair failed to back his minister, agreeing to the provisions and winning only the smallest of concessions - a review of the scheme in six months time. The summit's decision was an embarrassing rebuff for Mrs Beckett at her first major European meeting since succeeding Jack Straw. But British officials insisted she was happy to see a pilot scheme go ahead. Wolfgang Schüssel, the Chancellor of Austria and summit chairman, praised Britain for "withdrawing its concerns" about televising proceedings. "We are going to try to get a breath of fresh air into the European house and stimulate better public awareness," he said. -

Racism and New Labour

COOL BRITANNIA OR CRUEL BRITANNIA? RACISM AND NEW LABOUR H UW B EYNON AND L OU K USHNICK ost-war British society has witnessed a very significant inward migration of Ppeople from the ‘New Commonwealth’, and the complex diaspora this immigration has created in many British cities is widely recognized as having fundamentally altered British society. Some observers have emphasized the posi- tive aspects of the change, suggesting that the new kinds of identity and forms of living which it has produced have resulted in a transition towards an ethni- cally plural society. Others, while welcoming the changes, have drawn attention to the inequalities experienced by ethnic minorities and the persistence of racism in daily life, and in the major institutions of British society. The role of the state, and the ways in which ‘the race card’ has been played in British politics, have from the outset been the subject of extensive and often heated debate. A key focus of this debate has been crime and policing. In 1979 the Institute of Race Relations raised policing as a central issue for ethnic minorities in Britain. It concluded that there was powerful evidence to suggest that arrest and police powers were being used to keep the black community in its place both physically and psychologically.1 In 1983 the Policy Studies Institute extended this finding by examining the operation of the ‘sus’ law. This law (originally insti- tuted to control the working class in the early nineteenth century) made it a criminal offence to be ‘a suspicious person loitering with intent to commit a crime’. -

CLOSED MATERIAL PROCEDURES UNDER the JUSTICE and SECURITY ACT 2013 a Review of the First Report by the Secretary of State

CLOSED MATERIAL PROCEDURES UNDER THE JUSTICE AND SECURITY ACT 2013 A Review of the First Report by the Secretary of State Lawrence McNamara Daniella Lock Bingham Centre Working Paper 2014/03, August 2014 www.binghamcentre.biicl.org Citation: This paper should be cited as: L McNamara & D Lock, Closed Material Procedures Under the Justice and Security Act 2013: A Review of the First Report by the Secretary of State (Bingham Centre Working Paper 2014/03), Bingham Centre for the Rule of Law, BIICL, London, August 2014. Copyright: © Bingham Centre for the Rule of Law. This document is available for download from the Bingham Centre’s web site. It is not to be reproduced in any other form without the Centre’s express written permission. About the Bingham Centre Bingham Centre for the Rule of Law Charles Clore House 17 Russell Square London WC1B 5JP Tel: +44 (0)20 7862 5154 Email: [email protected] The Bingham Centre was launched in December 2010. The Centre is named after Lord Bingham of Cornhill KG, the pre-eminent judge of his generation and a passionate advocate of the rule of law. The Bingham Centre for the Rule of Law is an independent research institute devoted to the study and promotion of the rule of law worldwide. It is distinguished in the UK and internationally by its specific focus on the rule of law. Its focus is on understanding and promoting the rule of law; considering the challenges it faces; providing an intellectual framework within which it can operate; and fashioning the practical tools to support it. -

The World Economic Forum – a Partner in Shaping History

The World Economic Forum A Partner in Shaping History The First 40 Years 1971 - 2010 The World Economic Forum A Partner in Shaping History The First 40 Years 1971 - 2010 © 2009 World Economic Forum All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system. World Economic Forum 91-93 route de la Capite CH-1223 Cologny/Geneva Switzerland Tel.: +41 (0)22 869 1212 Fax +41 (0)22 786 2744 e-mail: [email protected] www.weforum.org Photographs by swiss image.ch, Pascal Imsand and Richard Kalvar/Magnum ISBN-10: 92-95044-30-4 ISBN-13: 978-92-95044-30-2 “Until one is committed, there is hesitancy, the chance to draw back, always ineffective, concerning all acts of initiative (and creation). There is one elementary truth the ignorance of which kills countless ideas and splendid plans: that the moment one definitely commits oneself, then providence moves too. All sorts of things occur to help one that would never otherwise have occurred. A whole stream of events issues from the decision, raising in one’s favour all manner of unforeseen incidents and meetings and material assistance which no man could have dreamed would have come his way. Whatever you can do or dream you can, begin it. Boldness has genius, power and magic in it. Begin it now.” Goethe CONTENTS Foreword 1 Acknowledgements 3 1971 – The First Year 5 1972 – The Triumph of an Idea 13 1973 – The Davos Manifesto 15 1974 – In the Midst of Recession 19 -

Monotheism's Eternal Triangle

VOLUME 1 No.12 DECEMBER 2001 Monotheism's eternal triangle ^i the three great monotheistic faiths - foreign intervention, showed how far is the key to the whole sorry saga - from Judaism, Christianity and Islam - tiie first that decline had gone. the rejection of partition plans to the 's undoubtedly tiie oldest and tiierefore, In Christian Europe, meanwhile, two spurning of Ehud Barak's olive branch however much tiiey may deny it, tiie divergent tendencies emerged. One was last year. "aspiration for the other two. It is also, secularisation, which allowed baptised, In Europe, meanwhile, white racists ^d has been for well over a millennium, or even unambiguous, Jews (Benjamin who target Muslims and Jews alike ^6 numerically smallest and thus the Disraeli, Adolphe Cremieux) to enter benefit from Muslim Judeophobia. In niostvuberable. governments. The opposite trend was France, the police chief Maurice Papon, f^rom the Destruction of the Temple to the increasing recourse to religious having deported Jews to the gas "le War of Israeli Independence, Jews dogma in Tsarist Russia and the appeal to chambers during the war, literally ^•"c not subjects, but near-passive racist gut feeling in Germany. drowned Algerian demonstrators in the "•ejects, of history. First Christianity tiien Seine in January 1961. But how could a ^lam swept triumphantly over case against Papon for Holocaust-related °ntinents, bringing vast swathes of the crimes ever be mounted if, according to Slobe under their dominion. (Today Muslim propaganda, the Holocaust is a 3tholicism and Islam number roughly 1 Zionist invention in support of a 'bogus' 'llion adherents each worldwide.) claim to a Jewish state in Palestine? ^ize matters, but it does not Another piece of hard-line Muslim ^cessarily confer commensurate power, propaganda is the depiction of Islam as a "ough backed by most of Europe, the faith transcending race and nationality. -

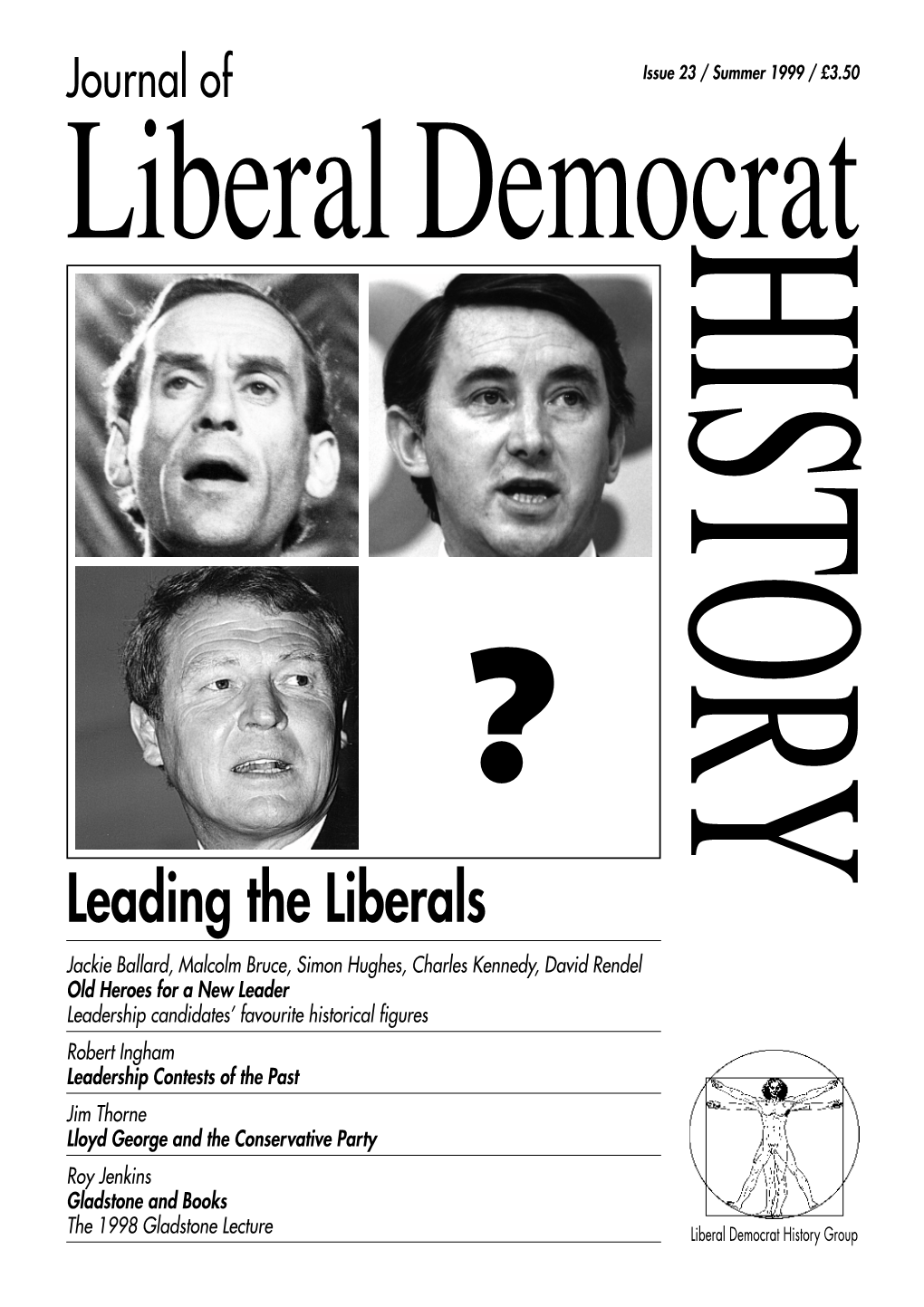

23 Leadership Candidates

Old Heroes for a New Leader Liberal Democrat leadership candidates describe their historical inspirations. The Liberal Democrat History Group asked all the wherever he found it, his humanity and warmth enabled him to communicate with people who five candidates for the Liberal Democrat leadership claimed not to be interested in politics, and he to write a short article for the Journal on their never took his feet off the ground. As a young favourite historical figure or figures – the ones they man he joined the Young Liberals, he cam- paigned from the grassroots up, fighting a felt had influenced their own political beliefs most, no-hope Parliamentary seat himself and en- and why they proved important and relevant. Their couraging others to stand as Liberals in local replies are printed below. elections. He was committed to community politics and to the liberal approach to local govern- ment. Penhaligon wanted to shake the estab- Jackie Ballard MP lishment and he wanted a different type of I instinctively recoil from the idea of heroes, council – devoted to the underdog, not wed- because inevitably, being human, they all have ded to nineteenth-century ritual but open and their flaws. For this reason, and because they accessible to the public. No campaigning work- would be horribly embarrassed, I’m not going shop is complete without someone quoting to write about my two living political heroes Penhaligon’s maxim: ‘If you have something to – Conrad Russell and Shirley Williams. say, stick it on a piece of paper and stuff it The real heroes in life are the people who through the letterbox’. -

The Rise of the Novice Cabinet Minister?

The Rise of the Novice Cabinet Minister? The Career Trajectories of Cabinet Ministers in British Government from Attlee to Cameron Some commentators have observed that today’s Cabinet ministers are younger and less experienced than their predecessors. To test this claim, we analyse the data for Labour and Conservative appointments to Cabinet since 1945. Although we find some evidence of a decline in average age and prior experience, it is less pronounced than for the party leaders. We then examine the data for junior ministerial appointments, which reveals that there is no trend towards youth and inexperience present lower down the hierarchy. Taking these findings together, we propose that public profile is correlated with ‘noviceness’; that is, the more prominent the role, the younger and less experienced its incumbent is likely to be. If this is correct, then the claim that we are witnessing the rise of the novice Cabinet minister is more a consequence of the personalisation of politics than evidence of an emerging ‘cult of youth’. Keywords: Cabinet ministers; junior ministers; party leaders; ministerial selection; personalisation; symbolic leadership Introduction In a recent article, Philip Cowley identified the rise of the novice political leader as a ‘major development’ in British politics. Noting the youth and parliamentary inexperience of David 1 Cameron, Ed Miliband and Nick Clegg at the point at which they acquired the leadership of their parties, Cowley concluded that: ‘the British now prefer their leaders younger than they used to [and] that this is evidence of some developing cult of youth in British politics’, with the desire for younger candidates inevitably meaning that they are less experienced. -

Steven Fielding

fielding jkt 10/10/03 2:18 PM Page 1 The Volume 1 Labour andculturalchange The LabourGovernments1964–1970 The Volume 1 Labour Governments Labour Governments 1964–1970 1964–1970 This book is the first in the new three volume set The Labour Governments 1964–70 and concentrates on Britain’s domestic policy during Harold Wilson’s tenure as Prime Minister. In particular the book deals with how the Labour government and Labour party as a whole tried to come to Labour terms with the 1960s cultural revolution. It is grounded in Volume 2 original research that uniquely takes account of responses from Labour’s grass roots and from Wilson’s ministerial colleagues, to construct a total history of the party at this and cultural critical moment in history. Steven Fielding situates Labour in its wider cultural context and focuses on how the party approached issues such as change the apparent transformation of the class structure, the changing place of women, rising black immigration, the widening generation gap and increasing calls for direct participation in politics. The book will be of interest to all those concerned with the Steven Fielding development of contemporary British politics and society as well as those researching the 1960s. Together with the other books in the series, on international policy and Fielding economic policy, it provides an unrivalled insight into the development of Britain under Harold Wilson’s premiership. Steven Fielding is a Professor in the School of Politics and Downloaded frommanchesterhive.comat09/30/202110:47:31PM Contemporary History at the University of Salford Steven Fielding-9781526137791 MANCHESTER via freeaccess MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS THE LABOUR GOVERNMENTS 1964–70 volume 1 Steven Fielding - 9781526137791 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/30/2021 10:47:31PM via free access fielding prelims.P65 1 10/10/03, 12:29 THE LABOUR GOVERNMENTS 1964–70 Series editors Steven Fielding and John W.