Key Lessons in Public Health Legal Preparedness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biden's Healthcare Influencers

September 9, 2020 Biden’s Healthcare Influencers What's Happening: With the close of Labor Day weekend and the unofficial end of summer, the Biden campaign is taking off in earnest. Healthcare continues to be a significant part of the overall campaign platform, both in how it relates to the coronavirus pandemic and in other more traditional health policy arenas such as prescription drug prices and health insurance. While the messaging out of the campaign is more focused on the day-to-day challenges of the pandemic and anti- Trump rhetoric, when the campaign pushes beyond the surface level discussions, health policy and the actions a Biden administration would take are top of mind for both staffers and voters. Why It Matters: The cliché exists for a reason: personnel is policy. With the Democratic Party focused on healthcare and the legacy of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) as one of its signature issues, working on these policies for a Democratic president represents major opportunities to advance long-held goals and the ability to move the party in a certain direction as there are still big intraparty disputes on the future of healthcare, particularly the Medicare-for-All debate. When reviewing the candidates for the top healthcare positions in a Biden administration, it is important to remember that just because some potential senior staff members have worked for industry, that does not mean that they would not then carry out policies that would have a negative impact on that same industry. In fact, to a long-time policy maker like Biden, their experience in the private sector means that they could understand the workings of industry that much more. -

Washington Update 444 N

National Association of State Auditors, Comptrollers and Treasurers WASHINGTON UPDATE 444 N. Capitol Street NW, Suite 234 Washington, DC 20001 March 11, 2013 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE President President Names New OMB Director issues for the MSRB. Suggested priorities MARTIN J. BENISON or initiatives should relate to any of the Comptroller Massachusetts President Barack Obama has nominated MSRB’s core activities: Sylvia Mathews Burwell, president of the First Vice President Regulating municipal securities dealers JAMES B. LEWIS Walmart Foundation, as the next director of State Treasurer the U.S. Office of Management and Budg- and municipal advisors. New Mexico et. She will take over for Jeffrey Zients, Operating market transparency sys- tems. Second Vice President who was named acting director of OMB in WILLIAM .G HOLLAND January 2012. Burwell previously worked Providing education, outreach and mar- Auditor General in the budget office as deputy director from ket leadership. Illinois 1998 to 2001 under President Bill Clinton, Secretary and she served as deputy chief of staff un- When providing feedback, the MSRB en- CALVIN McKELVOGUE der Jack Lew. Lew was confirmed as treas- courages commenters to be as specific as Chief Operating Officer possible and provide as much information State Accounting Enterprise ury secretary by the Senate two weeks ago. Iowa as possible about particular issues and top- Nunes to Resurrect Bill to Block Bond ics. In addition to providing the MSRB Treasurer with specific concerns about regulatory and RICHARD K. ELLIS Sales Without Pension Disclosure State Treasurer market transparency issues, the MSRB en- Utah Office of the State Treasurer Rep. Devin Nunes (R-CA) has indicated his courages commenters to provide input on its education, outreach and market leader- Immediate Past President intention to reintroduce his “Public Em- RONALD L. -

Annual Report 2018

2018Annual Report Annual Report July 1, 2017–June 30, 2018 Council on Foreign Relations 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10065 tel 212.434.9400 1777 F Street, NW, Washington, DC 20006 tel 202.509.8400 www.cfr.org [email protected] OFFICERS DIRECTORS David M. Rubenstein Term Expiring 2019 Term Expiring 2022 Chairman David G. Bradley Sylvia Mathews Burwell Blair Effron Blair Effron Ash Carter Vice Chairman Susan Hockfield James P. Gorman Jami Miscik Donna J. Hrinak Laurene Powell Jobs Vice Chairman James G. Stavridis David M. Rubenstein Richard N. Haass Vin Weber Margaret G. Warner President Daniel H. Yergin Fareed Zakaria Keith Olson Term Expiring 2020 Term Expiring 2023 Executive Vice President, John P. Abizaid Kenneth I. Chenault Chief Financial Officer, and Treasurer Mary McInnis Boies Laurence D. Fink James M. Lindsay Timothy F. Geithner Stephen C. Freidheim Senior Vice President, Director of Studies, Stephen J. Hadley Margaret (Peggy) Hamburg and Maurice R. Greenberg Chair James Manyika Charles Phillips Jami Miscik Cecilia Elena Rouse Nancy D. Bodurtha Richard L. Plepler Frances Fragos Townsend Vice President, Meetings and Membership Term Expiring 2021 Irina A. Faskianos Vice President, National Program Tony Coles Richard N. Haass, ex officio and Outreach David M. Cote Steven A. Denning Suzanne E. Helm William H. McRaven Vice President, Philanthropy and Janet A. Napolitano Corporate Relations Eduardo J. Padrón Jan Mowder Hughes John Paulson Vice President, Human Resources and Administration Caroline Netchvolodoff OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, Vice President, Education EMERITUS & HONORARY Shannon K. O’Neil Madeleine K. Albright Maurice R. Greenberg Vice President and Deputy Director of Studies Director Emerita Honorary Vice Chairman Lisa Shields Martin S. -

Complaint for Writ of Mandamus, to Which This Declaration Is Exhibit 4,)

Case 1:16-cv-00451 Document 1 Filed 03/08/16 Page 1 of 55 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA __________________________________________ ) ORACLE AMERICA, INC., ) a Delaware corporation ) 500 Oracle Parkway ) Redwood Shores, CA 94065 ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 16-451 ) SYLVIA MATHEWS BURWELL, ) Secretary, U.S. Department of Health ) and Human Services ) 200 Independence Avenue, S.W. ) Washington, DC 20201 ) ) Defendant. ) __________________________________________) COMPLAINT FOR A WRIT OF MANDAMUS Plaintiff Oracle America, Inc. (“Oracle”) brings this Complaint for a writ of mandamus to require Sylvia Mathews Burwell, in her official capacity as Secretary of the United States Department of Health and Human Services (“HHS”), to exercise her mandatory duty under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (“ACA”) to monitor the integrity and performance of states that receive Federal grant funds for the purpose of establishing state-based health insurance exchanges by: (a) directing the State of Oregon— HHS’s grantee—to seek to stay or dismiss the state-court lawsuit it has filed against Oracle and several Oracle employees for actions they allegedly took to assist Oregon with the creation of its Health Insurance Exchange (“HIX”); and (b) monitoring and investigating all work Oregon and its subgrantees and contractors, including Oracle, did on the Oregon 1 Case 1:16-cv-00451 Document 1 Filed 03/08/16 Page 2 of 55 HIX project in order to determine what liabilities involving Federal funds, if any, have arisen from the project. INTRODUCTION 1. HHS partnered with the State of Oregon through certain Cooperative Agreements to establish a state-run health insurance exchange (“the HIX”) under the ACA. -

United States Bankruptcy Court Southern District of Texas Mcallen Division Entered 06/06/2018 in Re: § La Fuente Home Health Services, § Case No: 14-70265 Inc

Case 16-07012 Document 49 Filed in TXSB on 06/06/18 Page 1 of 15 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS MCALLEN DIVISION ENTERED 06/06/2018 IN RE: § LA FUENTE HOME HEALTH SERVICES, § CASE NO: 14-70265 INC. § Debtor § § CHAPTER 11 § LA FUENTE HOME HEALTH SERVICES, § INC. § Plaintiff § § VS. § ADVERSARY NO. 16-07012 § SYLVIA MATHEWS BURWELL, et al § Defendants § JUDGE EDUARDO V. RODRIGUEZ MEMORANDUM OPINION DENYING PLAINTIFF’S AND DEFENDANT’S MOTIONS FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT Resolving ECF Nos. 36 & 37 I. Introduction Pending before the Court are two motions self-styled by the movants as “La Fuente Home Health Services, Inc.’s Motion for Summary Judgment and Brief in Support,” ECF No. 36 (“La Fuente’s Motion”), and the “Motion of Defendant Tom Price, Secretary of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, for Summary Judgment,” ECF No. 37 (“HHS’ Motion”). Both La Fuente Home Health Services, Inc. (“La Fuente”) and Tom Price, Secretary of the United States Department of Health and Human Services (“HHS”) seek summary judgment pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 56. In consideration of the arguments presented in the motions, all evidence in the record, and relevant case law, for the reasons stated in this Memorandum Opinion, this Court determines that both La Fuente’s and HHS’s dueling motions for summary judgment should be denied. Page 1 of 15 Case 16-07012 Document 49 Filed in TXSB on 06/06/18 Page 2 of 15 II. Procedural History On March 28, 2017, the Court entered its Memorandum Opinion Denying Defendant’s Motion to Dismiss Plaintiff’s Complaint and Application for Permanent Injunctive Relief and/or Alternatively for Summary Judgment. -

Download Legal Document

United States Court of Appeals For the Eighth Circuit ___________________________ No. 12-3357 ___________________________ Frank R. O’Brien, Jr.; O’Brien Industrial Holdings, LLC lllllllllllllllllllll Plaintiffs - Appellants v. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Sylvia Mathews Burwell, in her official capacity as the Secretary of the United States Department of Health and Human Services; United States Department of the Treasury; Jacob J. Lew, in his official capacity as the Secretary of the United States Department of the Treasury; United States Department of Labor; Thomas E. Perez, in his official capacity as Secretary of the United States Department of Labor lllllllllllllllllllll Defendants - Appellees1 ------------------------------ Catholic Medical Association; Christian Medical Association; Liberty, Life, and Law Foundation; Archdiocese of St. Louis; Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention; Women Speak for Themselves; Bioethics Defense Fund; Life Legal Defense Foundation; Association of American Physicians & Surgeons; National Catholic Bioethics Center; Institutional Religious Freedom Alliance; American Association of Pro-life Obstetricians & Gynecologists; Physicians for Life; National Association of Pro Life Nurses; Association of Gospel Rescue Missions; Prison Fellowship Ministries; Association of Christian Schools International; National Association of Evangelicals; Patrick Henry College; Christian Legal Society; David M. Wagner; 1Pursuant to Federal Rule of Appellate Procedure 43(c)(2), -

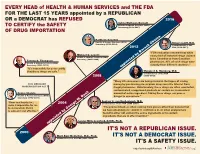

It's Not a Republican Issue. It's

EVERY HEAD of HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES and THE FDA FOR THE LAST 15 YEARS appointed by a REPUBLICAN OR a DEMOCRAT has REFUSED 2016 Sylvia Mathews Burwell Health & Human Services (HHS) TO CERTIFY the SAFETY Secretary (2014–2017) OF DRUG IMPORTATION Kathleen Sebelius Health & Human Services (HHS) Robert Califf, M.D. Secretary (2009–2014) Commissioner of the 2012 FDA (2016–2017) “FDA evaluation revealed that while Michael O. Leavitt nearly half of imported drugs claimed Health & Human Services (HHS) Secretary (2005–2009) to be Canadian or from Canadian Tommy G. Thompson Health & Human Services (HHS) pharmacies, 85% of such drugs were Secretary (2001–2005) actually from different countries.” appointed by Barack Obama “It's impossible for us to certify that these drugs are safe.” Margaret A. Hamburg, M.D. Commissioner of the FDA 2008 (2009–2015) “Many US consumers are being misled in the hopes of saving 2003 MEDICARE money by purchasing prescription drugs over the Internet from MODERNIZATION ACT illegal pharmacies. Unfortunately, these drugs are often counterfeit, contaminated, unapproved products or contain an inconsistent Donna Shalala amount of active ingredient. Taking these drugs can pose a Health & Human Services (HHS) danger to consumers.” Secretary (1993–2000) Andrew C. von Eschenbach, M.D. “flaws and loopholes... 2004 Commissioner of the FDA (2006–2009) make it impossible for me to demonstrate that it “The product itself...is often coming from places other than Canada that is safe and cost effective.” we have absolutely no control or confidence in, or when analyzed are found to either not contain the active ingredients or to contain ingredients that are in effect harmful.” Lester Mills Crawford, D.V.M., Ph.D. -

Nomination of Hon. Sylvia M. Burwell Hearing Committee

S. Hrg. 113–63 NOMINATION OF HON. SYLVIA M. BURWELL HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY AND GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOMINATION OF HON. SYLVIA M. BURWELL, TO BE DIRECTOR OF THE OFFICE OF MANAGEMENT AND BUDGET ARPIL 9, 2013 Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.fdsys.gov/ Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 80–570 PDF WASHINGTON : 2013 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY AND GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware Chairman CARL LEVIN, Michigan TOM COBURN, Oklahoma MARK L. PRYOR, Arkansas JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana RON JOHNSON, Wisconsin CLAIRE MCCASKILL, Missouri ROB PORTMAN, Ohio JON TESTER, Montana RAND PAUL, Kentucky MARK BEGICH, Alaska MICHAEL B. ENZI, Wyoming TAMMY BALDWIN, Wisconsin KELLY AYOTTE, New Hampshire HEIDI HEITKAMP, North Dakota RICHARD J. KESSLER, Staff Director LAWRENCE B. NOVEY, Chief Counsel for Governmental Affairs TROY H. CRIBB, Chief Counsel for Governmental Affairs KRISTINE V. LAM, Professional Staff Member DEIRDRE G. ARMSTRONG, Professional Staff Member KEITH B. ASHDOWN, Minority Staff Director ANDREW C. DOCKHAM, Minority Chief Counsel TRINA D. SHIFFMAN, Chief Clerk LAURA W. KILBRIDE, Hearing Clerk (II) C -

Supreme Court of the United States ------ ------DAVID KING, ET AL., Petitioners, V

No. 14-114 ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- --------------------------------- DAVID KING, ET AL., Petitioners, v. SYLVIA MATHEWS BURWELL, AS U.S. SECRETARY OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES, ET AL., Respondents. --------------------------------- --------------------------------- On Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Fourth Circuit --------------------------------- --------------------------------- BRIEF OF THE COMMONWEALTHS OF VIRGINIA, KENTUCKY, MASSACHUSETTS, AND PENNSYLVANIA, THE STATES OF CALIFORNIA, CONNECTICUT, DELAWARE, HAWAII, ILLINOIS, IOWA, MAINE, MARYLAND, MISSISSIPPI, NEW HAMPSHIRE, NEW MEXICO, NEW YORK, NORTH CAROLINA, NORTH DAKOTA, OREGON, RHODE ISLAND, VERMONT, AND WASHINGTON, AND THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF AFFIRMANCE --------------------------------- --------------------------------- MARK R. HERRING STUART A. RAPHAEL* Attorney General Solicitor General of Virginia of Virginia CYNTHIA BAILEY *Counsel of Record Deputy Attorney General TREVOR S. COX KIM PINER Deputy Solicitor General Senior Assistant OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY Attorney General GENERAL CARLY L. RUSH 900 East Main Street Assistant Attorney Richmond, Virginia 23219 General (804) 786-7240 January 28, 2015 [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae [Additional Counsel Listed On Signature Page] ================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2013 Digest of Other White House

Administration of Barack Obama, 2013 Digest of Other White House Announcements December 31, 2013 The following list includes the President's public schedule and other items of general interest announced by the Office of the Press Secretary and not included elsewhere in this Compilation. January 1 In the evening, the President traveled to Honolulu, HI, arriving the following morning. The White House announced that the President will travel to Honolulu, HI, in the evening. January 2 In the morning, upon arrival at Joint Base Pearl Harbor–Hickam, HI, the President traveled to Kailua, HI, where he had separate telephone conversations with Gov. Christopher J. Christie of New Jersey and Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo of New York to discuss Congressional action on the Hurricane Sandy supplemental request. In the afternoon, the President signed H.R. 8, the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012. During the day, the President had an intelligence briefing. He also signed H.R. 4310, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2013. January 3 In the morning, the President had a telephone conversation with House Republican Leader Eric Cantor and House Democratic Leader Nancy Pelosi to extend his welcome to all Members of the 113th Congress. In the afternoon, the President had a telephone conversation with Speaker of the House of Representatives John A. Boehner and House Democratic Leader Nancy Pelosi to congratulate them on being redesignated to lead their respective parties in the House. During the day, the President had an intelligence briefing. The President announced the designation of the following individuals as members of a Presidential delegation to attend the Inauguration of John Dramani Mahama as President of Ghana on January 7: Daniel W. -

Women Appointed to Presidential Cabinets

WOMEN APPOINTED TO PRESIDENTIAL CABINETS Eleven women have been confirmed to serve in cabinet (6) and cabinet level (5) positions in the Biden administration.1 A total of 64 women have held a total of 72 such positions in presidential administrations, with eight women serving in two different posts. (These figures do not include acting officials.) Among the 64 women, 41 were appointed by Democratic presidents and 23 by Republican presidents. Only 12 U.S presidents (5D, 7R) have appointed women to cabinet or cabinet-level positions since the first woman was appointed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933.2 Party breakdown of women appointed to Presidential Cabinets: 41D 23R Cabinet or Cabinet-level Firsts: First Woman First Black Woman First Latina First Asian Pacific First Native Appointed Appointed Appointed Islander Woman American Woman Appointed Appointed Frances Perkins Patricia Roberts Aída Álvarez Elaine Chao Debra Haaland Secretary of Labor Harris Administrator, Secretary of Labor Secretary of the 1933 (Roosevelt) Secretary of Small Business 2001 (G.W. Bush) Interior Housing and Urban Administration 2021 (Biden) Development 1997 (Clinton) 1977 (Carter) To date, 27 cabinet or cabinet-level posts have been filled by women. Cabinet and cabinet-level positions vary by presidential administration. Our final authority for designating cabinet or cabinet-level in an 1 This does not include Shalanda Young, who currently serves as Acting Director of the Office of Management and Budget. 2 In addition, although President Truman did not appoint any women, Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins, a holdover from the Roosevelt administration, served in his cabinet. © COPYRIGHT 2021 Center for American Women and Politic, Eagleton Institute of Politics, Rutgers University 4/6/2021 administration is that president's official library. -

Smartpower AMERICA’S ROLE in the WORLD AMERICA’S ROLE in the WORLD Welcome Letter Featured Speakers

FLORIDA ADVISORY COMMITTEE U.S. GLOBAL LEADERSHIP COALITION Honorary Co-Chairs Dr. Teo A. Babun, Jr. Gary Gould Dr. Susan Kaufman Purcell Executive Director, Americas Relief Team Chief Executive Officer, Tampa Bay Jewish Director, Center for Hemispheric Policy, University Hon. Jeb Bush Community Center and Federation of Miami Governor, State of Florida (1999-2007) Jonathan Baety Assistant Managing Partner, New England Nicole Shelley Greenidge Peter A. Quinter Hon. Donna E. Shalala Financial; National Liaison, Orlando Area Executive Director, The One on One Group Shareholder, Customs and International Trade Law AMERICA’S ROLE IN THE WORLD President, University of Miami; U.S. Secretary of Committee on Foreign Relations Group, GrayRobinson, P.A. Health and Human Services (1993-2001) Julie Grimes Oliver Barrett Managing Partner, Hilton Bentley Hotel Michael T. Raynor Director of Knowledge Management, Ducatus Senior Vice President, Corporate Banking, PNC Bank Hon. Michael I. Abrams Derrick Gruner Advisory LLC October 18, 2012 Director, Miami Policy Group, Akerman Senterfitt Managing Partner, Alvarez, Sambol, Winthrop P.A. Sherry Reeves Attorneys at Law Dr. Robert Beekman Ana Guevara Executive Director, Manufacturers Association of International Business Programs Coordinator, Central Florida Amb. Leslie M. Alexander President, AVENTI Associates, LLC Tampa, Florida University of Tampa U.S. Ambassador to Ecuador (1996-1999) Robert Hans Carolina Rendiero Patricia Beitler Founder & CEO, Business Centers International Hon. Dick J. Batchelor CEO, IOS Partners, Inc. President and Founder, Velocitas President, Dick Batchelor Management Group, Inc. Douglass J. Hillman Racquel “Rocky” Rodriguez Sharie A. Blanton Managing Member, McDonald Hopkins LLC Hon. Dean Cannon President and CEO, Aerosonic Corporation NGO Outreach, Global Reach Speaker, Florida House of Representatives Dr.