John William Graham (1859-1932)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Session Seven Materials (562-KB)

PENDLE HILL PAMPHLET 2 A Religious Solution To The Social Problem Howard H. Brinton PENDLE HILL PUBLICATIONS WALLINGFORD, PENNSYLVANIA HOWARD H. BRINTON 2 A Religious Solution To The Social Problem ABOUT THE AUTHOR Howard H.Brinton, Ph.D., Professor of Religion, Mills College; Acting Director, Pendle Hill, 1934-35. Published 1934 by Pendle Hill Republished electronically © 2004 by Pendle Hill http://www.pendlehill.org/pendle_hill_pamphlets.htm email: [email protected] HOWARD H. BRINTON 3 A Religious Solution To The Social Problem A religious solution to the social problem involves an answer to two preliminary questions — what social problem are we attempting to solve and what religion do we offer as a solution? Since religion has assumed a wide variety of forms it will be necessary, if we are to simplify and clarify our approach, to adopt at the outset a definite religious viewpoint. To define our premises as those of Christianity in general is not sufficiently explicit because historic Christianity has itself assumed a wide variety of forms. For the purpose of the present undertaking I shall approach our problem from the original point of view of the Society of Friends, which, in many ways, resembled that of early Christianity. Such an approach need not imply a narrow sectarian view. Early Quakerism exhibited certain characteristics common to many religious movements in their initial creative periods. Later Quakerism has shared the fate of other movements in failing to carry on the ideals of the founders. As for the social problem for which we seek a solution, it is the fundamental dilemma out of which most present-day social problems arise. -

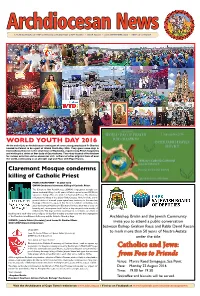

Catholics and Jews: and for the Sentiments Expressed

Archdiocesan News A PUBLICATION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH OF CAPE TOWN • ISSUE NO 81 • JULY-SEPTEMBER 2016 • FREE OF CHARGE WORLD YOUTH DAY 2016 At the end of July an Archdiocesan contingent of seven young people (and Fr Charles) headed to Poland to be a part of World Youth Day 2016. They spent some days in Czestochowa Diocese in the small town of Radonsko, experiencing Polish hospitality and visiting the shrine of Our Lady of Czestochowa. Then they headed off to Krakow for various activities and an encounter with millions of other pilgrims from all over the world, culminating in an all-night vigil and Mass with Pope Francis. Claremont Mosque condemns killing of Catholic Priest PRESS STATEMENT – 26 JULY 2016 CMRM Condemns Inhumane Killing of Catholic Priest The Claremont Main Road Mosque (CMRM) congregation strongly con- demns the brutal killing of an 85 year-old Catholic priest by two ISIS/Da`ish supporters during a Mass at a Church in Normandy, France. The inhumane and gruesome killing of the elderly Father Jacques Hamel and the sacrili- geous violation of a sacred prayer space bears testimony to the merciless ideology of Da`ish. It is apparent that Da`ish is hell-bent on fuelling a reli- gious war between Muslims and Christians. However, their war is a war on humanity and our response should reflect a deep respect for the sanctity of all human life. This tragic incident should spur us to redouble our efforts at reaching out to each other across religious divides. Our thoughts and prayers are with the congregation of the Church in Saint-Etienne-du-Rouvray and the Catholic Church at large. -

New Haven Friends Meeting November 2020 Starter List of Resources to Find out More About Quakers and Quakerism

New Haven Friends Meeting November 2020 Starter list of resources to find out more about Quakers and Quakerism The History of Friends: Most of the following resources are available through QuakerBooks of FGC or the Pendle Hill online bookstore. • Friends for 350 Years, Howard Brinton • Fit for Freedom, Not for Friendship: Quakers, African Americans, and the Myth of Racial Justice, Donna McDaniel and Vanessa Julye • Silence and Witness: The Quaker Tradition, Michael Birkel • Journal of George Fox • Journal of John Woolman • The Quiet Rebels: The Story of the Quakers in America, Margaret Hope Bacon • Portrait in Grey: A Short history of the Quakers, John Punshon • Quaker.org history section • How Quakerism Began, QuakerSpeak video Quaker Faith and Practice: • QuakerSpeak video on Testimonies: The Quaker Spices • New England Yearly Meeting (NEYM): Faith and Practice • A Testament of Devotion, Thomas R. Kelly • A Procession of Friends: Quakers in America, Daisy Newman • Friends Journal • 2014 Swarthmore Lecture (video), University of Bath, Ben Pink Dandelion • Pendle Hill Pamphlets in general, and specifically The Nature of Quakerism, by Howard H. Brinton Witness into Action: • Brother Outsider: The Life of Bayard Rustin (film) • The Vote, PBS series that mentions Alice Paul • A Journey Toward Eliminating Racism in the Religious Society of Friends, Vanessa Julye • QuakerSpeak video: Holding the Peace: Quaker Nonviolence in the Time of Black Lives Matter • New England Yearly Meeting’s Priorities for 2020-2021 o 2016 Minutes on Climate Change o A Letter of Apology to Indigenous Peoples (under revision) and a Call for Us to Act: https://neym.org/working-group-right-relationship-indigenous-peoples o A Call to Urgent Loving Action for the Earth and Her Inhabitants, which names the interconnected nature of “systemic problems of racism, social injustice, violence, greed, and failure to act on the climate crisis.” o The Outgoing Epistle of the 2020 Virtual Pre-Gathering of Friends of Color and their Families, Friends General Conference (FGC) . -

Cervantes and the Spanish Baroque Aesthetics in the Novels of Graham Greene

TESIS DOCTORAL Título Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene Autor/es Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Director/es Carlos Villar Flor Facultad Facultad de Letras y de la Educación Titulación Departamento Filologías Modernas Curso Académico Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene, tesis doctoral de Ismael Ibáñez Rosales, dirigida por Carlos Villar Flor (publicada por la Universidad de La Rioja), se difunde bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Unported. Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden solicitarse a los titulares del copyright. © El autor © Universidad de La Rioja, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2016 publicaciones.unirioja.es E-mail: [email protected] CERVANTES AND THE SPANISH BAROQUE AESTHETICS IN THE NOVELS OF GRAHAM GREENE By Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Supervised by Carlos Villar Flor Ph.D A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At University of La Rioja, Spain. 2015 Ibáñez-Rosales 2 Ibáñez-Rosales CONTENTS Abbreviations ………………………………………………………………………….......5 INTRODUCTION ...…………………………………………………………...….7 METHODOLOGY AND STRUCTURE………………………………….……..12 STATE OF THE ART ..……….………………………………………………...31 PART I: SPAIN, CATHOLICISM AND THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN (CATHOLIC) NOVEL………………………………………38 I.1 A CATHOLIC NOVEL?......................................................................39 I.2 ENGLISH CATHOLICISM………………………………………….58 I.3 THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN -

Russell and the Cambridge Moral Sciences Club L by Jack Pitt

Russell and the Cambridge Moral Sciences Club l by Jack Pitt IN HIS Autobiography Russell records his extreme satisfaction at being elected to the fraternal discussion group at Cambridge familiarly known as the Apostles. 2 In addition to including a number of congratulatory letters from elder Apostles, he writes: "The greatest happiness ofmy time at Cambridge was connected with a body whom its members knew as 'The Society,' but which outsiders, if they knew of it, called 'The Apostles.'''3 The sub sequent notoriety of this group obscured the fact that Russell I Gratitude is expressed to those at the University of Cambridge who kindly provided access to the Minutes of the Cambridge University Moral Sciences Club. The Minutes have been invaluable in constructing an historical context in which to locate Russell's participation in the Club, and in providing many details pertinent to that participation. 2 Its complete name is the Cambridge Conversazione Society. Its character and history is treated in Paul Levy's fascinating study, G. E. Moore and the Cam bridge Apostles (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1979). I am indebted to this book for many points of fact in this essay, especially as these concern members of the Society. The interested reader may also wish to consult Peter Allen's The Cambridge Apostles: The Early Years (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978). 3 Autobiography, 1872-1914 (Boston: Atlantic-Little, Brown, 1967), p. 91. 103 104 Russell winter 1981-82 Russell and the Cambridge Moral Sciences Club 105 maintained membership in other Cambridge societies. for The Athenaeum. Another of those in attendance was Alfred Philosophically the most important, and the one which will con Williams Momerie (Mummery), subsequently Professor of Logic cern us here, is the Cambridge University Moral Sciences Club and Metaphysics (1880-91) at King's College, London, and also (CUMSC). -

Ashby Library Catalogue

ASHBY LIBRARY CATALOGUE Abdel-Malek, A., Ed. (1982). Science and Technology in the Transformation of the World. Tokyo, United Nations University. Abdel-Malek, A. and A. N. Pandeya, Eds. (1981). Intellectual Creativity in Endogenous Culture. Tokyo, United Nations University. Abdulkadir, M. S. (2000). "Resistance to Colonial Taxation in Northern Nigeria in the 1930s." FAIS Journal of Humanities 1(2): 32-44. Abdullah, M. M. (1993). Valley of the Giant Buddhas. London, Octagon. Abulafia, A. S. (1995). Christians and Jews in the Twelfth-Century Renaissance. London, Routledge. Achebe, C. (1988). Anthills of the Savannah. New York, Anchor. Achebe, C. (1989). Hopes and Impediments. New York, Doubleday. Ackerman, B. (2006). Before the Next Attack. Preserving Civil Liberties in an Age of Terrorism. New Haven, Yale University. Ackerman, R. (1988). JG Frazer: His Life and Work. Cambridge, Cambridge University. Acort, P. A. (2008). Progress Utopia and Intellectual Practice. Arguments for the Resurrection of the Future, Bright Pen. Acourt, P. A. (2008). Progress, Utopia and Intellectual Practice. Arguments for the Resurrection of the Future, Bright Pen. Acrivos, J. V., et al., Eds. (1984). Physics and Chemistry of Electrons and Ions in Condensed Matter. Dordrecht, Reidel Publishing Co. Aguirre, M. S., et al. (2011). The Case of the "Big Seven" Basque Chefs. Zamudio, Innobasque. Ahlbrandt, C. D. and A. C. Peterson (1996). Discrete Hamiltonian Systems, Kluwer Academic. Airaksinen, T. (1995). The Philosophy of the Marquis de Sade. London, Routledge. Airaksinen, T. and M. A. Bertman, Eds. (1989). Hobbes: War Among Nations. Aldershot, Avebury. Alacevich, M. and A. Soci (2018). A Short History of Inequality. Brookings Institution, Washington, Agenda. -

Howard Brinton As a Theologian and Apologist for "Real Quakerism"

Quaker Religious Thought Volume 115 Article 3 1-1-2010 Howard Brinton as a Theologian and Apologist for "Real Quakerism" Anthony Manousos Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/qrt Part of the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Manousos, Anthony (2010) "Howard Brinton as a Theologian and Apologist for "Real Quakerism" ," Quaker Religious Thought: Vol. 115 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/qrt/vol115/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quaker Religious Thought by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Howard BRINTON AS A THEOLOGIAN AND APOLOGIST FOR “REAL QUAKERISM” anthony manouSoS critical understanding of 20th century Quaker theology would A be incomplete without assessing the contribution of Howard Brinton, whose works helped create the theological framework for modern liberal Quakerism. Given the importance and stature of the Brintons, I felt some trepidation about undertaking the daunting task of writing the first book-length biography about them. Fortunately, I had access to Howard Brinton’s unpublished autobiography, dictated to Yuki Brinton a year before his death in 1973, as well as to the Brinton archives at Haverford College and to his family and friends, who have been very supportive. But the lack of secondary material about the Brintons has made my scholarly efforts extremely challenging. As Ben Pink Dandelion, of Woodbrooke, has observed, Quakerism, and particular 20th century Quaker theology, is “vastly 1 under-researched.” Ironically, Brinton, one of the most important Quaker theologians of the 20th century, was never trained as a theologian. -

Liberal Education in York Since 1815, with Special Reference to Provision for Non-Vocational Adult Education

Durham E-Theses Liberal education in York since 1815, with special reference to provision for non-vocational adult education. Ashurst T. B, How to cite: Ashurst T. B, (1972) Liberal education in York since 1815, with special reference to provision for non-vocational adult education., Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9737/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 LIBERAL EDUCATION IN YORK SINCE 1815,, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO PROVISION FOR N ON-VOCATIONAL ADTJLT EDUCATION. A thesis submitted for examination for the degree of Master of Education in the University of Durham. Terence Bailey Ashurst, 1972. I ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS \ I wish to acknowledge the kind assistance of the Librarians of York City Library, St. John's College Llbrarjr, York, and the Rowntree-Mackintosh, York, Technical Library. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Most investigations of early twentieth-century Liberalism have centred on the politics of Campbell-Bannerman and Asquith's cabinets, the thought of Liberal intellectuals, and the struggles of local parties.1 But the world of the backbencher remains relatively obscure. When he has been studied, it has usually been in the mass as historians have sought to chart changes in the social background of Liberal MPs or tabulate their opinions, as expressed in parliamentary divisions, on topics like social reform or the relative merits of Asquith and Lloyd George.2 Much less is known about the lives of backbench MPs. This is largely because few of these men left any detailed records. The only published diary of a backbench Liberal MP for this period is that of R.D. Holt, MP for Hexham 1907-1918, and this can be supplemented by a handful of similar sources in archives around the country.3 The letters which Arnold Rowntree wrote to his wife, Mary, while he was MP for York in 1910-1918 provide an important addition to the existing material. They are particularly significant for three reasons. Firstly, Rowntree was, in many ways, a fairly typical Liberal backbencher. He was a middle-aged nonconformist businessman, sitting for a constituency that was his home and the location of his business. But he provides an important corrective to the idea that all men from this background were, like R.D. Holt, necessarily enemies of the New Liberalism. Secondly, Rowntree's letters are not just concerned with parlia- mentary politics. They cover all his interests, including his family, business, and religion and his charitable work. -

The 1825 Stockton & Darlington Railway

The 1825 S&DR: Preparing for 2025; Significance & Management. The 1825 Stockton & Darlington Railway: Historic Environment Audit Volume 1: Significance & Management October 2016 Archaeo-Environment for Durham County Council, Darlington Borough Council and Stockton on Tees Borough Council. Archaeo-Environment Ltd for Durham County Council, Darlington Borough Council and Stockton Borough Council 1 The 1825 S&DR: Preparing for 2025; Significance & Management. Executive Summary The ‘greatest idea of modern times’ (Jeans 1974, 74). This report arises from a project jointly commissioned by the three local authorities of Darlington Borough Council, Durham County Council and Stockton-on-Tees Borough Council which have within their boundaries the remains of the Stockton & Darlington Railway (S&DR) which was formally opened on the 27th September 1825. The report identifies why the S&DR was important in the history of railways and sets out its significance and unique selling point. This builds upon the work already undertaken as part of the Friends of Stockton and Darlington Railway Conference in June 2015 and in particular the paper given by Andy Guy on the significance of the 1825 S&DR line (Guy 2015). This report provides an action plan and makes recommendations for the conservation, interpretation and management of this world class heritage so that it can take centre stage in a programme of heritage led economic and social regeneration by 2025 and the bicentenary of the opening of the line. More specifically, the brief for this Heritage Trackbed Audit comprised a number of distinct outputs and the results are summarised as follows: A. Identify why the S&DR was important in the history of railways and clearly articulate its significance and unique selling point. -

An Introduction

Advent 2015 Issue 29 Let us pray for our is exemplary: plants synthesise related to warning, and their means of priests as they celebrate nutrients which feed herbivores; these subsistence are dependent on natural their birthdays and in turn become food for carnivores, reserves and ecosystemic services anniversaries. which produce significant quantities of such as agriculture, fishing and organic waste which give rise to new forestry. They have no other financial ANNIVERSARY OF generations of plants. But our activities or resources which can ORDINATION industrial system, at the end of its enable them to adapt to climate Southern Africa who in their Pastoral An introduction cycle of production and consumption, change or to face natural disasters, Just as the social Encyclical of Pope Statement on the Environmental December has not developed the capacity to and their access to social services Crisis (Sept '99) said: Everyone's Leo XIII Rerum Novarum created a absorb and reuse waste and by- 02.12.1995: Fr Alfred Ntuli and protection is very limited." (LS 25) talents and involvement are needed new focus of social justice for the products. We have not yet managed 02.12.2006: Fr Zamva Mlangeni "Our lack of response to these to redress the damage caused by teaching of the church in 1891 so to adopt a circular model of 07.12.2002: Fr Zakhele Ziqubu tradegies involving our brothers and human abuse of God's creation. Pope Laudato Si the encyclical of Pope production capable of preserving 11.12.2004: Fr Bongani Dladla sisters points to the loss of that sense Francis says that the "challenge to Francis on the care of our common resources for present and future 12.12.1980: Rt Rev Grahama Rose of responsibility for our fellow men protect our common home includes a home draws our attention today to generations, while limiting as much as 16.12.2009: Fr Mthokozisi Khanyile and women upon which all civil concern to bring the whole human ecology and the environment. -

Naughty Nuns and Promiscuous Monks: Monastic Sexual Misconduct in Late Medieval England

Naughty Nuns and Promiscuous Monks: Monastic Sexual Misconduct in Late Medieval England by Christian D. Knudsen A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of the Centre for Medieval Studies University of Toronto Copyright © by Christian D. Knudsen ABSTRACT Naughty Nuns and Promiscuous Monks: Monastic Sexual Misconduct in Late Medieval England Christian D. Knudsen Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Medieval Studies University of Toronto This dissertation examines monastic sexual misconduct in cloistered religious houses in the dioceses of Lincoln and Norwich between and . Traditionally, any study of English monasticism during the late Middle Ages entailed the chronicling of a slow decline and decay. Indeed, for nearly years, historiographical discourse surrounding the Dissolution of Monasteries (-) has emphasized its inevitability and presented late medieval monasticism as a lacklustre institution characterized by worsening standards, corruption and even sexual promiscuity. As a result, since the Dissolution, English monks and nuns have been constructed into naughty characters. My study, centred on the sources that led to this claim, episcopal visitation records, will demonstrate that it is an exaggeration due to the distortion in perspective allowed by the same sources, and a disregard for contextualisation and comparison between nuns and monks. In Chapter one, I discuss the development of the monastic ‘decline narrative’ in English historiography and how the theme of monastic lasciviousness came to be so strongly associated with it. Chapter two presents an overview of the historical background of late medieval English monasticism and my methodological approach to the sources. ii Abstract iii In Chapter three, I survey some of the broad characteristics of monastic sexual misconduct.