Agency Interpretations of Executive Orders Often Them

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baruch College EXECUTIVE ORDER 11246 AFFIRMATIVE ACTION PLAN (AAP)

Baruch College EXECUTIVE ORDER 11246 AFFIRMATIVE ACTION PLAN (AAP) September 1, 2017– August 31, 2018 PARTS I-VIII: AAP FOR MINORITIES AND WOMEN PART IX: AAP FOR INDIVIDUALS WITH DISABILITIES AND PROTECTED VETERANS Contact: Mona Jha, Esq. Chief Diversity Officer Baruch College One Bernard Baruch Way, Box C-204 New York, New York 10010 This is plan is available for public review at: http://www.baruch.cuny.edu/president/affirmativeaction.html The College has prepared this document in Accessible PDF format, available upon request. Please inform the Chief Diversity Officer at (646) 312-4538 if you require assistance with reading this document due to a disability Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 4 A. COLLEGE OVERVIEW .............................................................................................................................................. 4 B. HISTORY ................................................................................................................................................................. 5 C. MISSION ................................................................................................................................................................. 5 D. ORGANIZATION CHART .......................................................................................................................................... 5 II. NON-DISCRIMINATION AND AFFIRMATIVE ACTION POLICIES........................................................ -

Exploring the Limits of Executive Civil Rights Policymaking

Oklahoma Law Review Volume 61 Number 1 2008 Exploring the Limits of Executive Civil Rights Policymaking Stephen Plass St. Thomas University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/olr Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Law and Race Commons, and the President/ Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation Stephen Plass, Exploring the Limits of Executive Civil Rights Policymaking, 61 OKLA. L. REV. 155 (2008), https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/olr/vol61/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oklahoma Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXPLORING THE LIMITS OF EXECUTIVE CIVIL RIGHTS POLICYMAKING STEPHEN PLASS* Racial equality for blacks remains a minefield issue for American presidents. Any position a president takes is bound to alienate someone. As a result, even a well-meaning president such as Bill Clinton has had to tread very carefully when addressing this topic.1 Popular attitudes shaped by the powerful continue to dictate the extent to which presidents are able to confront continuing racial discrimination and its legacy of inequality in American life.2 Although many laws ordaining racial equality have been written, discrimination remains a normal part of life in America. This reality makes the President’s role in this area almost as difficult -

Executive Order 11375, Amending Executive Order 11246 Relating to Equal Employment Opportunity, and Implementing Regulations at 41C.F.R

2 C.F.R. § 200.326 and 2 C.F.R. Part 200, Appendix II, Required Contract Clauses 1. Remedies. a. Contracts for more than the simplified acquisition threshold ($150,000) must address administrative, contractual, or legal remedies in instances where contractors violate or breach contract terms, and provide for such sanctions and penalties as appropriate. See 2 C.F.R. Part 200, Appendix II, ¶ A. All remedies are stipulated in the Purchase Order Terms and Conditions. b. Applicability: This requirement applies to all FEMA grant, cooperative agreement programs, and City contracts that are funded through federal awards and grants. 2. Termination for Cause and Convenience. a. All contracts in excess of $10,000 must address termination for cause and for convenience by the non-Federal entity including the manner by which it will be effected and the basis for settlement. See 2 C.F.R. Part 200, Appendix II, ¶ B. b. Applicability. This requirement applies to all FEMA grant, cooperative agreement programs, and City contracts that are funded through federal awards and grants. The Termination for Cause and Convenience is in the City’s Purchase Order Terms and Conditions. 3. Equal Employment Opportunity. a. Except as otherwise provided under 41 C.F.R. Part 60, all contracts that meet the definition of "federally assisted construction contract" in 41 C.F.R. § 60-1.3 must include the equal opportunity clause provided under 41 C.F.R. § 60- 1.4(b), in accordance with Executive Order 11246, Equal Employment Opportunity (30 Fed. Reg. 12319, 12935, 3 C.F.R. Part, 1964-1965 Comp., p. -

Request for Qualifications and Proposals

REQUEST FOR QUALIFICATIONS AND PROPOSALS for HYDROLOGICAL, BIOLOGICAL, BOTANICAL, CULTURAL, AND COST PLANNING STUDY for the FORBES CREEK NEIGHBORHOOD IMPROVEMENT PROJECT CITY OF LAKEPORT Doug Grider, Public Works Director City of Lakeport 225 Park Street Lakeport, CA 95453 Funded by Community Development Block Grant Program February 22, 2021 Table of Contents I. BACKGROUND...................................................................................................................2 A. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 2 B. Background .................................................................................................................................... 2 II. PROJECT DESCRIPTION .............................................................................................2 III. SCOPE OF WORK. .........................................................................................................3 IV. PROPOSAL REQUIREMENTS .....................................................................................5 A. Identification of Prospective Consultant ........................................................................................ 5 B. Management ................................................................................................................................... 5 C. Personnel ....................................................................................................................................... -

Are Caas Federal Contractors and Do They Need Affirmative Action Plans?

Are CAAs Federal Contractors and Do They Need Affirmative Action Plans? September 2007, CAPLAW Update By Rafael Munoz, CAPLAW Some Community Action Agencies (CAAs) have received notification from the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) that the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs (OFCCP) will conduct a review of their compliance with a number of laws applicable to federal contractors, including requirements for affirmative action plans. Other CAAs have received a DOL “Equal Opportunity Survey” of federal contractors. Before responding to these communications, CAAs should review all of their grants and contracts to determine whether they are in fact “federal contractors” subject to OFCCP jurisdiction. In most cases, CAAs are not federal contractors and a letter to that effect should be sent to DOL. In addition, state contracts for Community Services Block Grant (CSBG), Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), Weatherization and other “pass-through” grants sometimes include language that requires CAAs to comply with the affirmative action rules that apply to federal contractors. If a CAA is not a federal contractor, it should explain this fact to the state and seek to have the language removed from its contract. (Keep in mind, though, that CAAs may be required to comply with state laws, regulations and executive orders on affirmative action, including a state requirement that they have an affirmative action plan.) As a general rule, because CAAs are federal grantees, rather than federal contractors, they are not required -

Executive Order 11246 Affirmative Action Plan (Aap)

2001 Oriental Boulevard Brooklyn, New York 11235 EXECUTIVE ORDER 11246 AFFIRMATIVE ACTION PLAN (AAP) Affirmative Action Program September 1, 2015 – August 31, 2016 PARTS I-V: AAP FOR MINORITIES AND WOMEN PART VI: AAP FOR COVERED VETERANS AND PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES Contact: Victoria A. Ajibade, Esq. Chief Diversity Officer Office of the President (718) 368-6896 AFFIRMATIVE ACTION PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION A. Description of College B. History C. Mission II. NON-DISCRIMINATION AND AFFIRMATIVE ACTION POLICIES III. DESIGNATION OF RESPONSIBILITY FOR IMPLEMENTATION A. President B. Chief Diversity/Affirmative Action Officer C. Executive Officers, Academic Chairpersons, Managers and Supervisory Personnel D. Diversity/Affirmative Action Committee IV. RESULTS OF STATISTICAL ANALYSES/AREAS OF CONCERN A. Workforce Analysis B. Job Group Summary C. Determining Availability D. Utilization Analysis/Comparison of Incumbency to Availability E. Comparison of 2014 Goals to 2015 Utilization Analysis Results F. Determining Adverse Impact 1. Analysis of Personnel Activity Table 2. Analysis of Applicant Data-Recruitment Documentation 3. Impact Ratio Analysis G. Tenure Eligibility Survey H. Analysis of Systemic Compensation V. ACTION - ORIENTED PROGRAMS A. Implementation of Affirmative Action Program 2014-2015 1. Goal Attainment 2. Initiatives and Activities 3. Dissemination of Non-Discrimination Policy and Programs B. Response to Fall 2015 Underutilization 1. Placement Goals for 2015 -2016 2. Employment Practices: Recruitment, Selection and Advancement C. Internal Audit and Reporting 1 VI. COVERED VETERANS AND INDIVIDUALS WITH DISABILITIES A. Review of Personnel Processes B. Review of Physical and Mental Job Qualifications C. Reasonable Accommodation to Physical and Mental Limitations D. Harassment Prevention Procedures E. External Dissemination of EEO Policy, Outreach and Positive Recruitment F. -

Presidential Authority to Impose Requirements on Federal Contractors

Presidential Authority to Impose Requirements on Federal Contractors Vanessa K. Burrows Legislative Attorney Kate M. Manuel Legislative Attorney January 10, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41866 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Presidential Authority to Impose Requirements on Federal Contractors Summary Executive orders requiring agencies to impose certain conditions on federal contractors as terms of their contracts have raised questions about presidential authority to issue such orders. Such executive orders typically cite the President’s constitutional authority, as well as his authority pursuant to the Federal Property and Administrative Services Act of 1949 (FPASA). FPASA authorizes the President to prescribe any policies or directives that he considers necessary to promote “economy” or “efficiency” in federal procurement. There have been legal challenges to orders (1) encouraging agencies to require the use of project labor agreements; (2) requiring that contracts include provisions obligating contractors to post notices informing employees of their rights not to be required to join a union or pay dues; and (3) directing departments to require contractors to use E-Verify to check the work authorization of their employees. These challenges have alleged, among other things, that the orders were beyond the President’s authority, under FPASA or otherwise. A 2011 draft executive order that would have directed departments to require contractors to “disclose certain political contributions and expenditures” raised similar and additional questions, as it resembled legislation that was considered, but not enacted, by the 111th Congress. The outcome of legal challenges to particular executive orders pertaining to federal contractors generally depends upon the authority under which the order was issued and whether the order is consistent with or conflicts with other statutes. -

PUBLISHED UNITED STATES COURT of APPEALS for the FOURTH CIRCUIT VOLVO GM HEAVY TRUCK CORPORATION, Plaintiff-Appellant, V

PUBLISHED UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT VOLVO GM HEAVY TRUCK CORPORATION, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF No. 96-2225 LABOR; ROBERT B. REICH, SECRETARY OF LABOR; SHIRLEY WILCHER, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Federal Contract Compliance Programs, Defendants-Appellees. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Western District of Virginia, at Roanoke. Jackson L. Kiser, Senior District Judge. (CA-96-40001-R) Argued: May 5, 1997 Decided: July 1, 1997 Before MURNAGHAN and HAMILTON, Circuit Judges, and LEGG, United States District Judge for the District of Maryland, sitting by designation. _________________________________________________________________ Affirmed by published opinion. Judge Murnaghan wrote the opinion, in which Judge Hamilton and Judge Legg joined. _________________________________________________________________ COUNSEL ARGUED: James Marion Powell, HAYNSWORTH, BALDWIN, JOHNSON & GREAVES, P.A., Greensboro, North Carolina, for Appellant. Samuel Robert Bagenstos, UNITED STATES DEPART- MENT OF JUSTICE, Washington, D.C., for Appellees. ON BRIEF: Gregory P. McGuire, HAYNSWORTH, BALDWIN, JOHNSON & GREAVES, P.A., Greensboro, North Carolina, for Appellant. Deval L. Patrick, Assistant Attorney General, Dennis J. Dimsey, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, Washington, D.C.; J. Davitt McAteer, Acting Solicitor, James D. Henry, Associate Solicitor, Debra A. Millenson, Senior Trial Attorney, Belinda Reed Shannon, Trial Attorney, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF LABOR, Washington, D.C., for Appellees. _________________________________________________________________ OPINION MURNAGHAN, Circuit Judge: On December 18, 1995, the Department of Labor's Office of Fed- eral Contract Compliance Programs (OFCCP) filed an administrative complaint under Executive Order 11246 alleging that in 1988 Volvo GM Heavy Truck Corporation had discriminated against female applicants for assembler positions in its Dublin, Virginia plant. -

FEMA Addendum #1 - Construction

FEMA Addendum #1 - Construction As certain funding for the project may be provided by or through the Federal Emergency Management Agency ("FEMA"), the Contractor further agrees as follows: Non-Discrimination. During the performance of the Work, the Contractor agrees to comply with Executive Order 11246 of September 24, 1965, entitled "Equal Employment Opportunity," as amended by Executive Order 11375 of October 13, 1967, and as supplemented in Department of Labor regulations 41 CFR chapter 60. Access to Books and Records. The Contractor agrees that any federal agency providing funding for the Contractor's Work, including FEMA and the Comptroller General of the United States, shall have access to the Contractor's books and records relating to the hourly compensation and Reimbursable Expenses for review, audit and reproduction. Compliance With Laws. The Contractor agrees to comply with the Contract Work Hours and Safety Standards Act, Chapter 37 (40 U.S.C. Sections 3701 et seq.), ; Clean Air Act (42 U.S.C. 7401 et seq.); Federal Water Pollution Control Act (33 U.S.C. 1251 et seq.). No Exclusion. The Contractor and each person signing on behalf of the Contractor represents and warrants that the Contractor and each parent and/or affiliate of the Contractor has not been suspended, disqualified, debarred or otherwise excluded from or declared ineligible to bid or perform work for any governmental agency or otherwise prohibited from participation in any federal or state program, including Medicare or Medicaid (collectively, “Program”), and to the best of its knowledge, there are no pending civil anti-trust or criminal investigations or pending or threatened debarments or exclusions of the Contractor from any Program. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27

Case 5:20-cv-07741-BLF Document 80 Filed 12/22/20 Page 1 of 34 1 2 3 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 4 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 5 SAN JOSE DIVISION 6 7 SANTA CRUZ LESBIAN AND GAY Case No. 20-cv-07741-BLF COMMUNITY CENTER d/b/a THE 8 DIVERSITY CENTER OF SANTA CRUZ, et al., ORDER GRANTING IN PART 9 PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR A Plaintiffs, NATIONWIDE PRELIMINARY 10 INJUNCTION v. 11 [Re: ECF 51] DONALD J. TRUMP, in his official 12 capacity as President of the United States, et al., 13 Defendants. 14 15 Plaintiffs are a number of non-profit community organizations and consultants serving the 16 lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (“LGBT”) community and people living with the human 17 immunodeficiency virus (“HIV”). Many of their clients are people of color, women, and LGBT United States District United States Court 1 Northern District of CaliforniaNorthern of District 18 people. Plaintiffs provide advocacy and training to health care providers, local government 19 agencies, local businesses, and their own employees about systemic bias, racism, anti-LGBT bias, 20 white privilege, implicit bias, and intersectionality. This training, Plaintiffs believe, is 21 fundamental to their mission of breaking down barriers that underserved communities face in 22 receiving health care. Plaintiffs bring this suit to challenge the constitutionality of Executive 23 Order 13950, which they contend has unlawfully labeled much of their work as “anti-American 24 propaganda.” 25 1 26 The Court adopts the terminology used in Plaintiffs’ brief, which refers to “LGBT” communities and “LGBT” people. See Mot. -

Executive Order 11246

Executive Order 11246 SOURCE: The following is the text of Executive Order 11246 of September 28, 1965, as it appears at 30 FR 12319, 12935, 3 CFR, 1964-1965 Comp., p.339, unless otherwise noted. Under and by virtue of the authority vested in me as President of the United States by the Constitution and statutes of the United States, it is ordered as follows: Part I — Nondiscrimination in Government Employment [Part I superseded by EO 11478 of Aug. 8, 1969, 34 FR 12985, 3 CFR, 1966-1970 Comp., p. 803] Part II - Nondiscrimination in Employment by Government Contractors and Subcontractors Subpart A - Duties of the Secretary of Labor SEC. 201.The Secretary of Labor shall be responsible for the administration and enforcement of Parts II and III of this Order. The Secretary shall adopt such rules and regulations and issue such orders as are deemed necessary and appropriate to achieve the purposes of Parts II and III of this Order. [Sec. 201 amended by EO 12086 of Oct. 5, 1978, 43 FR 46501, 3 CFR, l978 Comp., p. 230] Subpart B - Contractors' Agreements SEC. 202. Except in contracts exempted in accordance with Section 204 of this Order, all Government contracting agencies shall include in every Government contract hereafter entered into the following provisions: During the performance of this contract, the contractor agrees as follows: 1. The contractor will not discriminate against any employee or applicant for employment because of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. The contractor will take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed, and that employees are treated during employment, without regard to their race, color, religion, sex or national origin. -

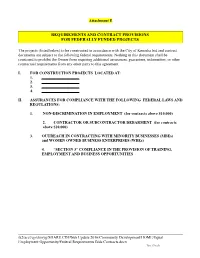

Requirements and Contract Provisions for the Project

Attachment E REQUIREMENTS AND CONTRACT PROVISIONS FOR FEDERALLY FUNDED PROJECTS The projects (listed below) to be constructed in accordance with the City of Kenosha bid and contract documents are subject to the following federal requirements. Nothing in this document shall be construed to prohibit the Owner from requiring additional assurances, guarantees, indemnities, or other contractual requirements from any other party to this agreement. I. FOR CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS LOCATED AT: 1. 2. 3. 4. II. ASSURANCES FOR COMPLIANCE WITH THE FOLLOWING FEDERAL LAWS AND REGULATIONS: 1. NON-DISCRIMINATION IN EMPLOYMENT (for contracts above $10,000) 2. CONTRACTOR OR SUBCONTRACTOR DEBARMENT (for contracts above $10,000) 3. OUTREACH IN CONTRACTING WITH MINORITY BUSINESSES (MBEs) and WOMEN OWNED BUSINESS ENTERPRISES (WBEs) 4. “SECTION 3” COMPLIANCE IN THE PROVISION OF TRAINING, EMPLOYMENT AND BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES /u2/acct/cp/ctonyg/SHARE.CDI/Web Update 2016/Community Development/HOME/Equal Employment Opportunity/Federal Requirements Bids Contracts.docx Date (fixed) Attachment E ASSURANCES FOR COMPLIANCE WITH THE FOLLOWING FEDERAL LAWS AND REGULATIONS The contractor is required to comply with the Federal laws and regulations in regard to non- discrimination in employment, Section 3 Requirements and contractor and subcontractor debarment: 1. Non-discrimination in Employment: The contractor is required to comply with Executive Order 11246 of September 24, 1965 entitled “Equal Employment Opportunity” as amended by Executive Order 11375 of October 13, 1967. The contract for the work under this proposal will obligate the prime contractor and its subcontractors not to discriminate in employment practices. The contractor shall not maintain or provide for his/her employees the facilities, which are segregated on a basis of race, creed, color, or national origin, whether such facilities are segregated by directive or on a de facto basis.