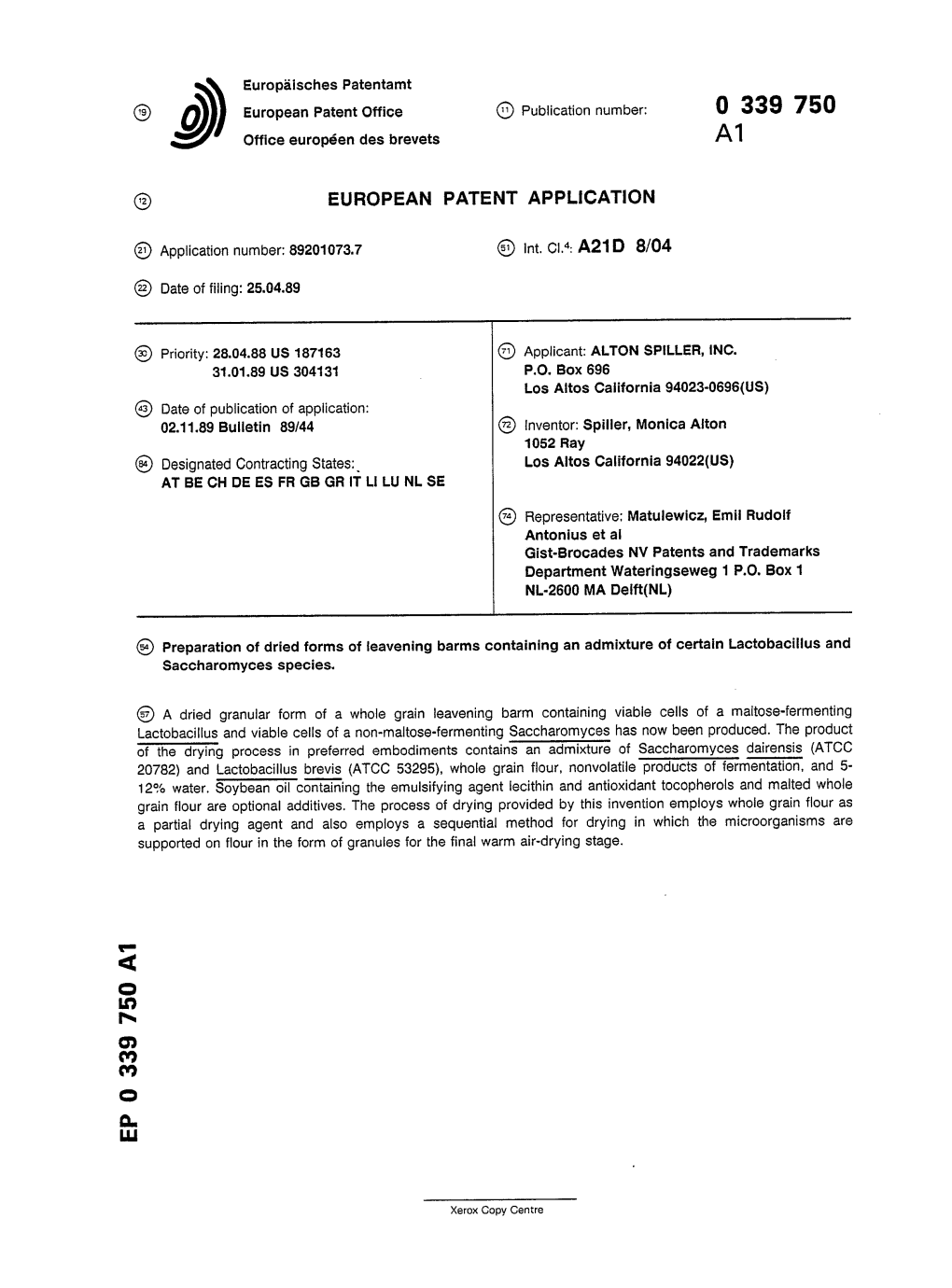

Preparation of Dried Forms of Leavening Barms Containing an Admixture of Certain Lactobaciilus and Saccharomyces Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brewing Yeast – Theory and Practice

Brewing yeast – theory and practice Chris Boulton Topics • What is brewing yeast? • Yeast properties, fermentation and beer flavour • Sources of yeast • Measuring yeast concentration The nature of yeast • Yeast are unicellular fungi • Characteristics of fungi: • Complex cells with internal organelles • Similar to plants but non-photosynthetic • Cannot utilise sun as source of energy so rely on chemicals for growth and energy Classification of yeast Kingdom Fungi Moulds Yeast Mushrooms / toadstools Genus > 500 yeast genera (Means “Sugar fungus”) Saccharomyces Species S. cerevisiae S. pastorianus (ale yeast) (lager yeast) Strains Many thousands! Biology of ale and lager yeasts • Two types indistinguishable by eye • Domesticated by man and not found in wild • Ale yeasts – Saccharomyces cerevisiae • Much older (millions of years) than lager strains in evolutionary terms • Lot of diversity in different strains • Lager strains – Saccharomyces pastorianus (previously S. carlsbergensis) • Comparatively young (probably < 500 years) • Hybrid strains of S. cerevisiae and wild yeast (S. bayanus) • Not a lot of diversity Characteristics of ale and lager yeasts Ale Lager • Often form top crops • Usually form bottom crops • Ferment at higher temperature o • Ferment well at low temperatures (18 - 22 C) (5 – 10oC) • Quicker fermentations (few days) • Slower fermentations (1 – 3 weeks) • Can grow up to 37oC • Cannot grow above 34oC • Fine well in beer • Do not fine well in beer • Cannot use sugar melibiose • Can use sugar melibiose Growth of yeast cells via budding + + + + Yeast cells • Each cell is ca 5 – 10 microns in diameter (1 micron = 1 millionth of a metre) • Cells multiply by budding a b c d h g f e Yeast and ageing - cells can only bud a certain number of times before death occurs. -

Multiple Genetic Origins of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae in Bakery

Multiple genetic origins of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in bakery Frédéric Bigey, Diego Segond, Lucie Huyghe, Nicolas Agier, Aurélie Bourgais, Anne Friedrich, Delphine Sicard To cite this version: Frédéric Bigey, Diego Segond, Lucie Huyghe, Nicolas Agier, Aurélie Bourgais, et al.. Multiple genetic origins of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in bakery. Comparative genomics of eukaryotic microbes: genomes in flux, and flux between genomes, Oct 2019, Sant Feliu de Guixol, Spain. hal-02950887 HAL Id: hal-02950887 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02950887 Submitted on 28 Sep 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. genetic diversity of229 propagating a natural sourdough, which is a of mixed naturally fermented domestication of wide diversity of fermented products like wine, Saccharomyces cerevisiae sake, beer, cocoa and bread. While bread is of cultural and historical importance, the highly diverse environments like human, wine, sake, fruits, tree, soil... fruits, tree, human, wine, sake, like highly diverse environments clade on the 1002 genomes whichtree, also includes beer strains. Sourdough strains mosaic are and genetically are to related strains from strains. Selection for strains commercial has maintained autotetraploid. strains mostly to Commercial are related strains of origin the Mixed The origin of bakery strains is polyphyletic. -

Relation Between the Recipe of Yeast Dough Dishes and Their Glycaemic Indices and Loads

foods Article Relation between the Recipe of Yeast Dough Dishes and Their Glycaemic Indices and Loads Ewa Raczkowska * , Karolina Ło´zna , Maciej Bienkiewicz, Karolina Jurczok and Monika Bronkowska Department of Human Nutrition, Faculty of Biotechnology and Food Sciences, Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences, 51-630 Wroclaw, Poland * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-71-320-7726 Received: 23 July 2019; Accepted: 30 August 2019; Published: 1 September 2019 Abstract: The aim of the study was to evaluate the glycaemic indices (GI) and glycaemic loads (GL) of four food dishes made from yeast dough (steamed dumplings served with yoghurt, apple pancakes sprinkled with sugar powder, rolls with cheese and waffles with sugar powder), based on their traditional and modified recipes. Modification of the yeast dough recipe consisted of replacing wheat flour (type 500) with whole-wheat flour (type 2000). Energy value and the composition of basic nutrients were assessed for every tested dish. The study was conducted on 50 people with an average age of 21.7 1.1 years, and an average body mass index of 21.2 2.0 kg/m2. The GI of the analysed ± ± food products depended on the total carbohydrate content, dietary fibre content, water content, and energy value. Modification of yeast food products by replacing wheat flour (type 500) with whole-wheat flour (type 2000) contributed to the reduction of their GI and GL values, respectively. Keywords: glycaemic index; glycaemic load; yeast dough 1. Introduction In connection with the growing number of lifestyle diseases, consumers pay increasing attention to food, not only to food that have a better taste but also to food that help maintain good health. -

Sensory Evaluation and Staling of Bread Produced by Mixed Starter of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae and L.Plantarum

J. Food and Dairy Sci., Mansoura Univ., Vol. 5 (4): 221 - 233, 2014 Sensory evaluation and staling of bread produced by mixed starter of saccharomyces cerevisiae and l.plantarum Swelim, M. A. / Fardous M. Bassouny / S. A. El-Sayed / Nahla M. M. Hassan / Manal S. Ibrahim. * Botany Department, Faculty of science, Banha University. ** Agricultural Microbiology Department, Agricultural Research Center, Giza, Egypt. ***Food Technology Research Institute, Agricultural Research Center, Giza, Egypt. ABSTRACT Impact of processed conditions and type of starter cultivars on characteristics of wheat dough bread by using mixed starter cultivars of Sacch. cerevisiae and L. plantarum was estimated. L. plantarum seemed to be more effective in combination with Sacch. cerevisiae on the dough volume. Dough produced by starter containing L. plantarum characterized with lower PH and higher total titratable acidity (TTA) and moisture content, in comparison with control treatment. Highly significant differences in aroma and crumb texture were recorded with bread produced by starter culture containing L. plantarum. The obtained results also revealed significant differences in bread firmness which reflected the staling and its rate among the tested treatments after 1, 3, 5 and 6 days during storage time at room temperature. Data also confirmed a processing technique using L. planturium mixed with Sacch.cerevisia to enhance organoleptic properties of produced bread. INTRODUCTION Cereal fermentation is one of the oldest biotechnological processes, dating back to ancient Egypt, where both beer and bread were produced by using yeasts and lactic acid bacteria (LAB), Clarke and Arendt, (2005). Starters composed of specific individual LAB, or mixed with yeasts, became available a few years ago allowing the production of a full sourdough in one- stage process. -

AP-42, CH 9.13.4: Yeast Production

9.13.4 Yeast Production 9.13.4.1 General1 Baker’s yeast is currently manufactured in the United States at 13 plants owned by 6 major companies. Two main types of baker’s yeast are produced, compressed (cream) yeast and dry yeast. The total U. S. production of baker’s yeast in 1989 was 223,500 megagrams (Mg) (245,000 tons). Of the total production, approximately 85 percent of the yeast is compressed (cream) yeast, and the remaining 15 percent is dry yeast. Compressed yeast is sold mainly to wholesale bakeries, and dry yeast is sold mainly to consumers for home baking needs. Compressed and dry yeasts are produced in a similar manner, but dry yeasts are developed from a different yeast strain and are dried after processing. Two types of dry yeast are produced, active dry yeast (ADY) and instant dry yeast (IDY). Instant dry yeast is produced from a faster-reacting yeast strain than that used for ADY. The main difference between ADY and IDY is that ADY has to be dissolved in warm water before usage, but IDY does not. 9.13.4.2 Process Description1 Figure 9.13.4-1 is a process flow diagram for the production of baker’s yeast. The first stage of yeast production consists of growing the yeast from the pure yeast culture in a series of fermentation vessels. The yeast is recovered from the final fermentor by using centrifugal action to concentrate the yeast solids. The yeast solids are subsequently filtered by a filter press or a rotary vacuum filter to concentrate the yeast further. -

Introduction to Baking and Pastries Chef Tammy Rink with William R

Introduction to Baking and Pastries Chef Tammy Rink With William R. Thibodeaux PH.D. ii | Introduction to Baking and Pastries Introduction to Baking and Pastries | iii Introduction to Baking and Pastries Chef Tammy Rink With William R. Thibodeaux PH.D. iv | Introduction to Baking and Pastries Introduction to Baking and Pastries | v Contents Preface: ix Introduction to Baking and Pastries Topic 1: Baking and Pastry Equipment Topic 2: Dry Ingredients 13 Topic 3: Quick Breads 23 Topic 4: Yeast Doughs 27 Topic 5: Pastry Doughs 33 Topic 6: Custards 37 Topic 7: Cake & Buttercreams 41 Topic 8: Pie Doughs & Ice Cream 49 Topic 9: Mousses, Bavarians and Soufflés 53 Topic 10: Cookies 56 Notes: 57 Glossary: 59 Appendix: 79 Kitchen Weights & Measures 81 Measurement and conversion charts 83 Cake Terms – Icing, decorating, accessories 85 Professional Associations 89 vi | Introduction to Baking and Pastries Introduction to Baking and Pastries | vii Limit of Liability/disclaimer of warranty and Safety: The user is expressly advised to consider and use all safety precautions described in this book or that might be indicated by undertaking the activities described in this book. Common sense must also be used to avoid all potential hazards and, in particular, to take relevant safety precautions concerning likely or known hazards involving food preparation, or in the use of the procedures described in this book. In addition, while many rules and safety precautions have been noted throughout the book, users should always have adult supervision and assistance when working in a kitchen or lab. Any use of or reliance upon this book is at the user's own risk. -

Sourdough” Became a Nickname for Gold Prospectors, As the Bread Was a Major Part of Their Meal

“Sourdough” Became A Nickname For Gold Prospectors, As The Bread Was A Major Part Of Their Meal National Sourdough Bread Day on April 1st recognizes one of the world’s oldest leavened breads. Most likely the first form of leavening available to bakers, it is believed sourdough originated in Ancient Egyptian times around 1500 BC. During the European Middle Ages, it also remained the usual form of leavening. As part of the California Gold Rush, sourdough was the principal bread made in Northern California and is still a part of the culture of San Francisco today. The bread was so common at that time the word “sourdough” became a nickname for the gold prospectors. In The Yukon and Alaska, a “sourdough” is also a nickname given to someone who has spent an entire winter north of the Arctic Circle. It refers to their tradition of protecting their sourdough during the coldest months by keeping it close to their body. The sourdough tradition was also carried into Alaska and western Canadian territories during the Klondike Gold Rush. San Francisco sourdough is the most famous sourdough bread made in the United States today. In contrast to sourdough production in other areas of the country, the San Francisco variety has remained in continuous production since 1849, with some bakeries able to trace their starters back to California’s Gold Rush period. The liquid alcohol layer referred to as ‘hooch’ comes from a Native American tribe called Hoochinoo. The Hoochinoo used to trade supplies with Alaskan gold miners for the ‘hooch’ off the top of their sourdough starters. -

Quick Breads

FN-SSB.923 Quick Breads KNEADS A LITTLE DOUGH While baking yeast bread may be intimidating to some people, there are some “quick” options to get you started in the kitchen. Muffins, coffeecakes, scones, waffles, and pancakes are all breads that can be made in a short period of time and with very little effort. The difference between yeast breads and quick breads is the leavening agent. Yeast is a living cell that multiplies rapidly when given the proper food, moisture, and warmth. It must “proof”, or rise, to allow the production of carbon dioxide that allows the bread to rise during baking. Quick breads use the chemical leavening agents of baking powder and/or baking soda. Baking powder and baking soda do not require time for rising, so the batter for quick bread is cooked immediately after mixing. The best thing about quick breads is that the options are limitless when it comes to ingredients. The limiting factor in good quick breads is the correct mixing. Over mixing or under mixing will result in a poor quality product. BASIC INGREDIENTS Different quick bread batters are created by varying the ingredients and combining them in a certain way to form the structure of the bread. The possibilities are endless, but the common factor is the basic ingredients of fat, sugar, eggs, flour, liquid, leavening agent, and a flavoring ingredient. The flavoring might be a fruit or vegetable, a liquid such as buttermilk or fruit juice, an extract, herbs, or spices. Depending how the ingredients are mixed together will determine the texture and quality. -

14419802.Pdf

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE REVIEW ARTICLE 277 Potential Application of Yeast β-Glucans in Food Industry Vesna ZECHNER-KRPAN 1 Vlatka PETRAVIĆ-TOMINAC 1 ( ) Ines PANJKOTA-KRBAVČIĆ 2 Slobodan GRBA 3 Katarina BERKOVIĆ 4 Summary Diff erent β-glucans are found in a variety of natural sources such as bacteria, yeast, algae, mushrooms, barley and oat. Th ey have potential use in medicine and pharmacy, food, cosmetic and chemical industries, in veterinary medicine and feed production. Th e use of diff erent β-glucans in food industry and their main characteristics important for food production are described in this paper. Th is review focuses on benefi cial properties and application of β-glucans isolated from diff erent yeasts, especially those that are considered as waste from brewing industry. Spent brewer’s yeast, a by-product of beer production, could be used as a raw-material for isolation of β-glucan. In spite of the fact that large quantities of brewer’s yeast are used as a feedstuff , certain quantities are still treated as a liquid waste. β-Glucan is one of the compounds that can achieve a greater commercial value than the brewer’s yeast itself and maximize the total profi tability of the brewing process. β-Glucan isolated from spent brewer’s yeast possesses properties that are benefi cial for food production. Th erefore, the use of spent brewer’s yeast for isolation of β-glucan intended for food industry would represent a payable technological and economical choice for breweries. -

Impact of Wort Amino Acids on Beer Flavour: a Review

fermentation Review Impact of Wort Amino Acids on Beer Flavour: A Review Inês M. Ferreira and Luís F. Guido * LAQV/REQUIMTE, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade do Porto, Rua do Campo Alegre, 687, 4169-007 Porto, Portugal; ines.fi[email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +351-220-402-644 Received: 3 March 2018; Accepted: 25 March 2018; Published: 28 March 2018 Abstract: The process by which beer is brewed has not changed significantly since its discovery thousands of years ago. Grain is malted, dried, crushed and mixed with hot water to produce wort. Yeast is added to the sweet, viscous wort, after which fermentation occurs. The biochemical events that occur during fermentation reflect the genotype of the yeast strain used, and its phenotypic expression is influenced by the composition of the wort and the conditions established in the fermenting vessel. Although wort is complex and not completely characterized, its content in amino acids indubitably affects the production of some minor metabolic products of fermentation which contribute to the flavour of beer. These metabolic products include higher alcohols, esters, carbonyls and sulfur-containing compounds. The formation of these products is comprehensively reviewed in this paper. Furthermore, the role of amino acids in the beer flavour, in particular their relationships with flavour active compounds, is discussed in light of recent data. Keywords: amino acids; beer; flavour; higher alcohols; esters; Vicinal Diketones (VDK); sulfur compounds 1. Introduction The process by which beer has been brewed has not changed significantly since its discovery over 2000 years ago. Although industrial equipment is used for modern commercial brewing, the principles are the same. -

Paper Title: FOOD ADDITIVES

Paper No.: 13 Paper Title: FOOD ADDITIVES Module – 21 : Raising agents, Glazing agents and Sequesterants for the food industry 21.1 Introduction Raising agents, Glazing agents and Sequesterants have their distinct role in various food products. Important raising or leavening agents, glazing agents and sequestering agents used for the food industry are discussed in this module. 21.2 Raising agents for the food industry Raising agent or Leavening Agent is a substance used to produce or stimulate production of carbon dioxide in baked goods in order to impart a light texture, including yeast, yeast foods, and calcium salts. It is a substance or combination of substances which liberate gas and there by increased volume of a dough. Different raising agents are discussed below: 21.2.1 Calcium carbonate Calcium carbonate is a naturally occurring mineral (chalk or limestone), but the food- grade material is made by reaction of calcium hydroxide with carbon dioxide, followed by purification by flotation. It is used as a colour, a source of carbon dioxide in raising agents, an anti-caking agent, a source of calcium and a texturising agent in chewing gum. Calcium carbonate is used in chewing gum and in bread. 21.2.2 Calcium phosphates The calcium phosphates are manufactured by the reaction of hydrated lime and phosphoric acid under conditions controlled to maximize the yield of the required product. Monocalcium phosphate Monocalcium phosphate is used as a raising agent when rapid reaction with sodium bicarbonate is required. Dicalcium phosphate Dicalcium phosphate is available in both dihydrate and anhydrous forms. The dihydrate is used as a raising agent in combination with other phosphates and sodium bicarbonate. -

Mead Features Fermented by Saccharomyces Cerevisiae (Lalvin K1-1116)

African Journal of Biotechnology Vol. 12(2), pp. 199-204, 9 January, 2013 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/AJB DOI: 10.5897/AJB12.2147 ISSN 1684–5315 ©2013 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Mead features fermented by Saccharomyces cerevisiae (lalvin k1-1116) Eduardo Marin MORALES1*, Valmir Eduardo ALCARDE2 and Dejanira de Franceschi de ANGELIS1 1Department of Biochemistry and Microbiology, Institute of Biosciences, UNESP - Univ Estadual Paulista, Av. 24-A, 1515, 13506-900, Rio Claro, SP, Brazil. 2UNIMEP – Methodist University of Piracicaba. Rodovia Santa Bárbara Km 1, 13450-000 - Santa Barbara D'Oeste, SP, Brazil. Accepted 5 December, 2012 Alcoholic beverages are produced practically in every country in the world representing a significant percentage of the economy. Mead is one of the oldest beverages and it is easily obtained by the fermentation of a mixture of honey and water. However, it is still less studied compared to other beverages and does not have industrialized production. It is prepared as a handmade product. The origin of the honey used to formulate the mead creates differences on the final product characteristics. In this study, fermentation occurred at temperatures of about 22.1 ± 0.4°C after a previous pasteurization and inoculation. Saccharomyces cerevisiae (K1-LALVIN 1116) was used to produce the mead that was prepared in order to obtain dry mead by mixing 200 g L-1 of honey in water. For better -1 -1 results inorganic salts were used [(NH4)2SO4: 0.2 g L , (NH4)2HPO4: 0.02 g L ]. The results at the end of the process were a mead with: 12.5 ± 0.4°GL; pH 3.33; low amounts of high alcohols and methanol and great quantity of esters, that provide a nailing flavor to the beverage.