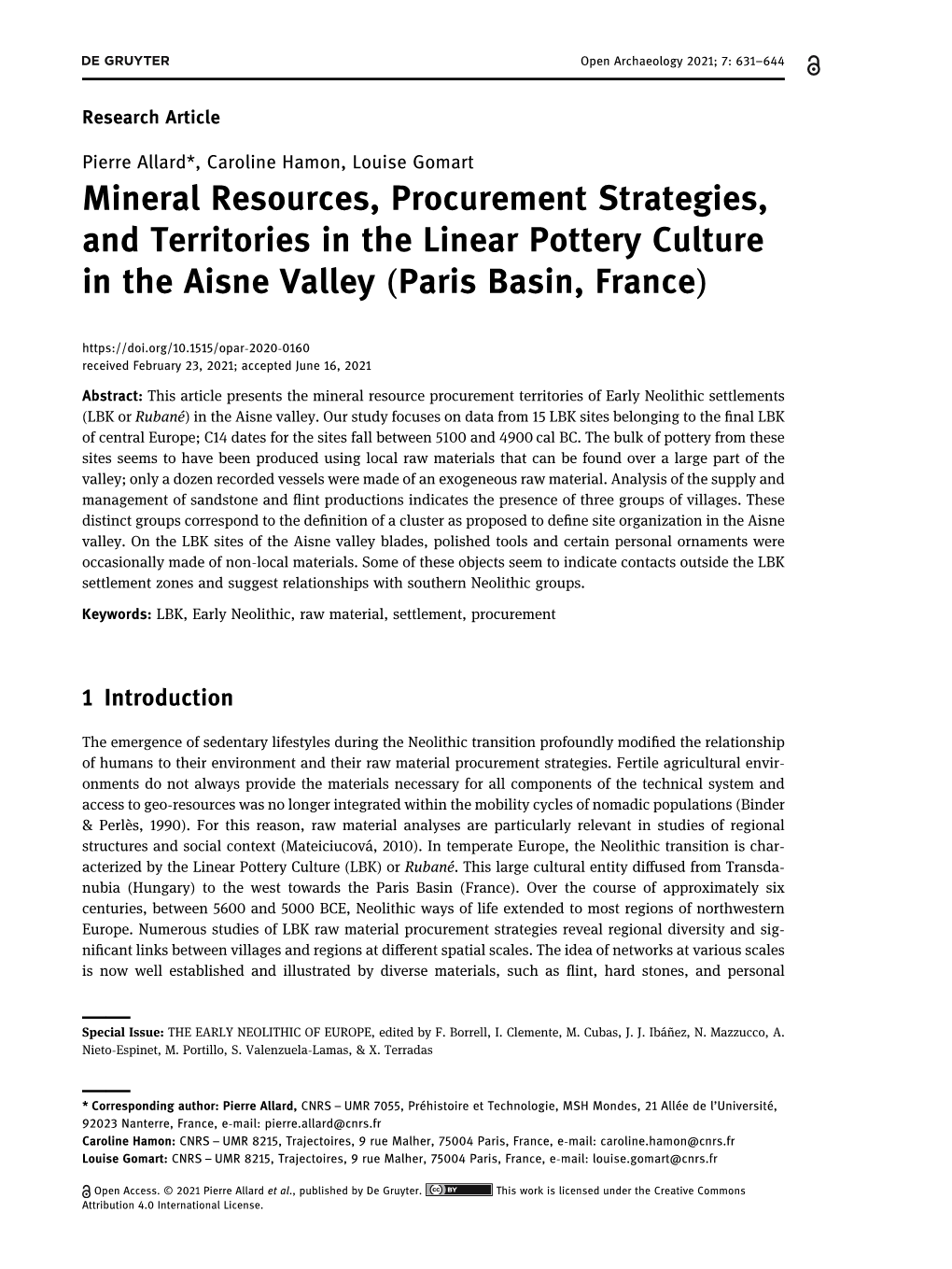

Degruyter Opar Opar-2020-0160 631..644 ++

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CC Du Chemin Des Dames (Siren : 240200592)

Groupement Mise à jour le 01/07/2021 CC du Chemin des Dames (Siren : 240200592) FICHE SIGNALETIQUE BANATIC Données générales Nature juridique Communauté de communes (CC) Commune siège Craonne Arrondissement Laon Département Aisne Interdépartemental non Date de création Date de création 29/12/1995 Date d'effet 29/12/1995 Organe délibérant Mode de répartition des sièges Répartition de droit commun Nom du président M. Jean-Paul COFFINET Coordonnées du siège Complément d'adresse du siège 1 rue de l'Eglise Numéro et libellé dans la voie Distribution spéciale Code postal - Ville 02160 Craonne Téléphone 03 23 22 47 84 Fax 03 23 22 47 84 Courriel [email protected] Site internet www.cc-chemindesdames.fr Profil financier Mode de financement Fiscalité additionnelle sans fiscalité professionnelle de zone et sans fiscalité professionnelle sur les éoliennes Bonification de la DGF non Dotation de solidarité communautaire (DSC) non Taxe d'enlèvement des ordures ménagères (TEOM) non Autre taxe non Redevance d'enlèvement des ordures ménagères (REOM) non Autre redevance non 1/4 Groupement Mise à jour le 01/07/2021 Population Population totale regroupée 5 588 Densité moyenne 31,14 Périmètre Nombre total de communes membres : 30 Dept Commune (N° SIREN) Population 02 Aizelles (210200077) 124 02 Aubigny-en-Laonnois (210200333) 107 02 Beaurieux (210200572) 861 02 Berrieux (210200713) 190 02 Bouconville-Vauclair (210200994) 195 02 Bourg-et-Comin (210201034) 828 02 Braye-en-Laonnois (210201117) 201 02 Chermizy-Ailles (210201653) 108 02 Chevregny (210201703) -

The Campaign of 1814: Chapter 17, Part XI

The Napoleon Series The Campaign of 1814: Chapter 17, Part XI By: Maurice Weil Translated by: Greg Gorsuch THE CAMPAIGN OF 1814 (after the documents of the imperial and royal archives of Vienna) _____________________ THE ALLIED CAVALRY DURING THE CAMPAIGN OF 1814 ________________________ CHAPTER XVII. OPERATIONS OF THE ALLIED GREAT ARMY AGAINST THE MARSHELS UP TO THE MARCH OF THE EMPEROR ON ARCIS-SUR-AUBE. -- OPERATIONS AGAINST THE EMPEROR UP TO THE REUNION WITH THE ARMY OF SILESIA. -- OPERATIONS OF THE ARMY OF SILESIA FROM 18 TO 23 MARCH. -- OPERATIONS OF THE EMPEROR AND THE ALLIED ARMIES DURING THE DAY OF MARCH 24. _________ ARCIS-SUR-AUBE. Second disposition of Schwarzenberg. --Orders of movement for the night of the 23rd to 24th. --At 4 o'clock, Schwarzenberg sent from Pougy the following disposition:1 "The army will march on Châlons in a manner to be the 24th at daybreak at the level of Vésigneul-sur-Coole and be able to continue its movement as circumstances dictate." "The Crown Prince of Württemberg will move as quickly as possible on Châlons, occupying this city and taking position in a fashion to cover the march of the other corps and protect their passage of the Marne. The guards will follow. Their column head will arrive at 9 o'clock in the evening at Sompuis, that the left of the VIth Corps will have quit at that time." "The Vth Corps will come to establish in Faux-sur-Coole and Songy-sur-Marne. The march of this corps should be 1Prince Schwarzenberg, Pougy, 23 March, 4 o'clock. -

ZRR - Zone De Revitalisation Rurale : Exonération De Cotisations Sociales

ZRR - Zone de Revitalisation Rurale : exonération de cotisations sociales URSSAF Présentation du dispositif Les entreprises en ZRR (Zone de Revitalisation Rurale) peuvent être exonérée des charges patronales lors de l'embauche d'un salarié, sous certaines conditions. Ces conditions sont notamment liées à son effectif, au type de contrat et à son activité. Conditions d'attribution A qui s’adresse le dispositif ? Entreprises éligibles Toute entreprise peut bénéficier d'une exonération de cotisations sociales si elle respecte les conditions suivantes : elle exerce une activité industrielle, commerciale, artisanale, agricole ou libérale, elle a au moins 1 établissement situé en zone de revitalisation rurale (ZRR), elle a 50 salariés maximum. Critères d’éligibilité L'entreprise doit être à jour de ses obligations vis-à-vis de l'Urssaf. L'employeur ne doit pas avoir effectué de licenciement économique durant les 12 mois précédant l'embauche. Pour quel projet ? Dépenses concernées L'exonération de charges patronales porte sur le salarié, à temps plein ou à temps partiel : en CDI, ou en CDD de 12 mois minimum. L'exonération porte sur les assurances sociales : maladie-maternité, invalidité, décès, assurance vieillesse, allocations familiales. URSSAF ZRR - Zone de Revitalisation Rurale : exonération de cotisations sociales Page 1 sur 5 Quelles sont les particularités ? Entreprises inéligibles L'exonération ne concerne pas les particuliers employeurs. Dépenses inéligibles L'exonération de charges ne concerne pas les contrats suivants : CDD qui remplace un salarié absent (ou dont le contrat de travail est suspendu), renouvellement d'un CDD, apprentissage ou contrat de professionnalisation, gérant ou PDG d'une société, employé de maison. -

La Bataille De Berry-Au-Bac

1917 BATAILLE LA BATAILLE DE BERRY AU-BAC LE BAPTÊME RATÉ DES CHARS FRANÇAIS Le 16 avril 1917, les premiers « appareils » [1] français sont engagés au combat dans le cadre de l’offensive du Chemin des Dames conçue par le généralissime Nivelle. Leur participation est un échec sanglant, marqué à la fois par le choix d’attaquer un secteur particulièrement bien défendu et par l’emploi de tactiques de combat inadaptées. Par Sylvain Ferreira 68 La bataille de Berry-au-Bac Sur cette photo, on voit clairement le canon de 75 BS (Blockhaus Schneider), dont l’angle de tir est limité par sa position. Il doit permettre d’engager les nids de mitrailleuses allemands avec précision jusqu’à 200 m. On distingue également une des deux mitrailleuses Hotchkiss installées sur chaque flanc pour notamment prendre les tranchées allemandes en enfilade. logiquement subi un revers opérationnel important. LES PREMIÈRES DOCTRINES Les Britanniques ont également balayé du revers de Le 20 août 1916, dans le cadre de la constitution de la main les objections formulées par Estienne lors ce qui s’appelle l’Artillerie spéciale (AS), le colonel de sa visite à Lincoln en juin 1916 pour estimer Estienne, qui supervise sa création, rédige une pre- l’avancement du programme britannique. mière instruction [2] sur l’emploi des chars d’assaut, Suite au retour d’expérience anglais, Estienne, dans laquelle il décrit les modalités d’utilisation de qui deviendra général de brigade le 17 octobre, cette nouvelle Arme. Selon Estienne, les « appareils » revoit intégralement sa copie sur la doctrine d’em- doivent pouvoir prendre l’offensive sur un vaste front ploi des chars français, qu’il décide de modifier en afin de pénétrer enfin le dispositif allemand dans la deux phases. -

Liste Communes Par Troncon

LISTE DES COMMUNES CONCERNEES PAR LA VIGILANCE CRUES BASSIN DE L’OISE TRONCON COMMUNES ACHERY MESBRECOURT RICHECOURT AGNICOURT ET SECHELLES MEZIERES-SUR-OISE ALAINCOURT MONCEAU SUR OISE ANGUILCOURT LE SART MONTCORNET ASSIS SUR SERRE MONTIGNY SOUS MARLE AUTREPPES MONTIGNY SUR CRECY BERNOT MONT D’ORIGNY BERTHENICOURT MONDREPUIS BOSMONT SUR SERRE MORTIERS BRISSAY-CHOIGNY MOY-DE-L’AISNE BRISSY-HAMEGICOURT NEUVE-MAISON CHALANDRY NEUVILETTE CHAOURSE NOUVION ET CATILLON CHARMES NOUVION LE COMTE CHATILLON-SUR-OISE NOYALES CHIGNY OHIS CILLY ORIGNY EN THIERACHE COURBES ORIGNY-SAINTE-BENOITE CRECY SUR SERRE POUILLY SUR SERRE DERCY PROISY OISE-AMONT DEUILLET PROIX EFFRY QUIERZY ENGLANCOURT REMIES ERLON RIBEMONT ERLOY ROMERY ETREAUPONT SAINT-ALGIS FLAVIGNY LE GRAND ET BEAURAIN SAINT-PIERREMONT GERGNY SERY-LES-MEZIERES GUISE SISSY HAUTEVILLE SORBAIS HIRSON TAVAUX-PONTSERICOURT LA BOUTEILLE THENELLES LA NEUVILLE-BOSMONT TRAVECY LESQUIELLES SAINT GERMAIN VADENCOURT LUZOIR VENDEUIL MACQUIGNY VOYENNE MALZY WIEGE-FATY MARCY SOUS MARLE WIMY MARLE MARLY-GOMONT MAYOT BASSIN DE L’OISE TRONCON COMMUNES ABBECOURT CHAUNY OGNES AMIGNY-ROUY CONDREN SERVAIS ANDELAIN DANIZY SINCENY OISE MOYENNE AUTREVILLE LA FERE TERGNIER BEAUTOR MANICAMP VIRY NOUREUIL BICHANCOURT MAREST-DAMPCOURT - 25 - BASSIN DE L’AISNE TRONCON COMMUNES ACY MISSY SUR AISNE AMBLENY MONTIGNY-LENGRAIN BEAURIEUX MOUSSY-VERNEUIL BERNY-RIVIERE OEUILLY BERRY-AU-BAC OSLY-COURTIL BOURG-ET-COMIN PARGNAN BUCY LE LONG PASLY CELLES SUR AISNE PERNANT CHASSEMY POMMIERS CHAUDARDES PONT-ARCY CHAVONNE PONTAVERT AISNE -

Supplementary Information for Ancient Genomes from Present-Day France

Supplementary Information for Ancient genomes from present-day France unveil 7,000 years of its demographic history. Samantha Brunel, E. Andrew Bennett, Laurent Cardin, Damien Garraud, Hélène Barrand Emam, Alexandre Beylier, Bruno Boulestin, Fanny Chenal, Elsa Cieselski, Fabien Convertini, Bernard Dedet, Sophie Desenne, Jerôme Dubouloz, Henri Duday, Véronique Fabre, Eric Gailledrat, Muriel Gandelin, Yves Gleize, Sébastien Goepfert, Jean Guilaine, Lamys Hachem, Michael Ilett, François Lambach, Florent Maziere, Bertrand Perrin, Susanne Plouin, Estelle Pinard, Ivan Praud, Isabelle Richard, Vincent Riquier, Réjane Roure, Benoit Sendra, Corinne Thevenet, Sandrine Thiol, Elisabeth Vauquelin, Luc Vergnaud, Thierry Grange, Eva-Maria Geigl, Melanie Pruvost Email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], Contents SI.1 Archaeological context ................................................................................................................. 4 SI.2 Ancient DNA laboratory work ................................................................................................... 20 SI.2.1 Cutting and grinding ............................................................................................................ 20 SI.2.2 DNA extraction .................................................................................................................... 21 SI.2.3 DNA purification ................................................................................................................. 22 SI.2.4 -

Les Continuités Ecologiques Régionales En Hauts-De-France

CHAMBRY Les Continuités Ecologiques MARCHAIS LAPPION Régionales en Hauts-de-France ATHIES-SOUS-LAON SAMOUSSY LA SELVE A1 A2 A3 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 NIZY-LE-COMTE C1 C2 C3 C4 C5 C6 LAON COUCY-LES-EPPES SISSONNE D1 D2 D3 D4 D5 D6 D7 EPPES MONTAIGU E1 E2 E3 E4 E5 E6 E7 F1 F2 F3 F4 F5 F6 F7 G1 G2 G3 G4 G5 G6 PARFONDRU VESLUD H1 H2 H3 H4 H5 H6 LOR I1 I2 I3 I4 MAUREGNY-EN-HAYE FESTIEUX CONTINUITES ECOLOGIQUES SAINT-ERME-OUTRE-ET-RAMECOURT LA MALMAISON COURTRIZY-ET-FUSSIGNY CHERET MONTCHALONS Réservoirs de biodiversité Réservoirs de Biodiversité de la trame bleue (cours d'eau de la liste 2 + réservoirs biologiques des Sdage) ORGEVAL SAINT-THOMAS Réservoirs de Biodiversité de la trame verte AMIFONTAINE ARRANCY AUBIGNY-EN-LAONNOIS Corridors principaux GOUDELANCOURT-LES-BERRIEUX BIEVRESPLOYART-ET-VAURSEINE Corridors boisés MARTIGNY-COURPIERRE Attention: les corridors écologiques, AIZELLES Corridors humides au contraire des réservoirs, ne sont BERRIEUX PROUVAIS pas localisés précisément par le SAINTE-CROIX schéma. Ils doivent être compris PROVISEUX-ET-PLESNOY Corridors littoraux comme des "fonctionnalités écologiques", c'est-à-dire des Corridors ouverts caractéristiques à réunir entre deux réservoirs pour répondre aux besoins des espèces (faune NEUVILLE-SUR-AILETTE Corridors multitrames et flore) et faciliter leurs échanges BOUCONVILLE-VAUCLAIR génétiques et leur dispersion. CORBENY Corridors fluviaux CHERMIZY-AILLES EVERGNICOURT Zones à enjeux CERNY-EN-LAONNOIS JUVINCOURT-ET-DAMARY Zones à enjeu d'identification de corridors bocagers CRAONNE G GUIGNICOURT -

Villages Disparus

CIRCUIT des Villages Calais Circuit routier Bruxelles Lille artez à la découverte des Distance Temps Particularité Repères A26 villages disparus du Chemin des A1 disparus Dames et revivez le destin tragique 35 km 1 à 4 heures Ce circuit n'est Suivez le Amiens du Chemin des Dames (parcours pas une boucle jalonnement de ces lieux de mémoire. Sur chaque complet) routier RD 18 CD A29 Laon site, un panneau d'information (lignes latérales Rouen Soissons bleues) A4 Reims retrace leur passé. RN2 A26 Mémorial de Musée du Paris Mémorial de Musée du Cerny-en-Laonnois Chemin des Dames Cerny-en-Laonnois Chemin des Dames Laon Laon Laon Laon Pancy-Courtecon Chamouille Pancy-Courtecon Chamouille Monampteuil Chermizy-Ailles Monampteuil Chermizy-Ailles Lac de Lac de D2 Chavignon Monampteuil Corbeny D2 Chavignon Monampteuil Corbeny L’Ailette Bouconville-Vauclair L’Ailette Bouconville-Vauclair Laffaux Lac de l’Ailette Retrouvez tout le Chemin des Dames sur Laffaux Lac de l’Ailette A B K A B K Vieux Ailles E D1044 www.cc-chemindesdames.fr Vieux Ailles E D1044 Chemin d Courtecon Cerny J Chemin d Courtecon Cerny J RD 18 CD C RD 18 CD C Vieux Chevreux A 26 Vieux Chevreux A 26 es Beaulne D es Beaulne D Dames H Craonne Dames H Craonne Soissons et Chivy L Soissons et Chivy L Braye-en-Laonnois Troyon La Vallée Craonne Braye-en-Laonnois Troyon La Vallée Craonne Vailly/Aisne Foulon Vailly/Aisne Foulon Craonnelle Craonnelle Vendresse- F G La Ville-aux-Bois Vendresse- F G La Ville-aux-Bois Beaulne Paissy lès-Pontavert Beaulne Paissy lès-Pontavert Vassogne Vassogne L’Aisne Moussy-Verneuil Berry-au-Bac L’Aisne Moussy-Verneuil Berry-au-Bac (Courtonne) Autres sites (Courtonne) Beaurieux Reims Beaurieux Reims L’Aisne L’Aisne Vallée de l’Aisne A Moulin de Laffaux Vallée de l’Aisne B Fort de Malmaison C Cerny-en-Laonnois Mémorial du Chemin des Dames D Caverne du Dragon, musée du Chemin des Dames, Constellation de la Douleur Vieux-Craonne En 1931 la gestion du site E Ruines de l'Abbaye de Vauclair a été confiée aux Eaux et Forêts (actuel ONF). -

Travaux De Désembâclement De La Rivière Aisne Programme 2 Tranche 3

UNION DES SYNDICATS D’AMENAGEMENT ET DE GESTION DES MILIEUX AQUATIQUES Service technique _______ Syndicat intercommunal pour la gestion du bassin versant de l’Aisne axonaise non navigable et de ses affluents Travaux de désembâclement de la rivière Aisne Programme 2 Tranche 3 _____ Compte-rendu de la réunion de piquetage du 25 septembre 2018 Lieu : Parking place de la mairie de Guignicourt à 9h30 Maître d’ouvrage : Maître d’œuvre : Entreprise : Syndicat intercommunal pour la gestion du bassin versant de l’Aisne Union des Syndicats d’Aménagement et NINO MASCITTI SA axonaise non navigable et de ses de Gestion des Milieux Aquatiques affluents Nom, Prénom: Organisme : Présent Absent Excusé GILET Rémy Président du SIGMAA x DEZUROT Raymond Membre du bureau du SIGMAA x BOMBART Marcel Membre du bureau du SIGMAA x HUCHET William Union des Syndicats de rivières x SCHLOSSER Joël DRIEE Ile de France (service police de l’eau) x DUCAT Philippe Vice-Président de la CCCP x FAVEREAU Gilles Délégué de Condé-sur-Suippe x LEGRAND Colette Délégué de Menneville x ROBERT Alain Délégué de Pignicourt x DEGHAYE Patricia Délégué de Bourg-et-Comin x CARAMELLE Bertrand Maire de Pargnan X RASERO Philippe Délégué de Pontavert X BARBIER Mickael MASCITTI NINO X BOUSSARD François Agence de l’eau Seine-Normandie x • Cette réunion de piquetage concerne les travaux de désembâclement sur la rivière Aisne (tranche 3). Ces travaux ont été confiés, après appel d’offres, à l’entreprise NINO MASCITTI SA – (siège : 6, rue des Bucherons – B.P. 78 – 02 602 VILLERS COTTERETS). 1 SITUATION ACTUELLE : Suite au diagnostic des embâcles réalisé durant le mois de mai 2018, 52 embâcles présentant un risque ont été inventoriés et doivent être traités par l’entreprise. -

Rankings Municipality of Cuiry- Lès-Chaudardes

9/29/2021 Maps, analysis and statistics about the resident population Demographic balance, population and familiy trends, age classes and average age, civil status and foreigners Skip Navigation Links FRANCIA / HAUTS DE FRANCE / Province of AISNE / Cuiry-lès-Chaudardes Powered by Page 1 L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin Adminstat logo DEMOGRAPHY ECONOMY RANKINGS SEARCH FRANCIA Municipalities Powered by Page 2 Abbécourt Stroll up beside >> L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin Erloy AdminstatAchery logo DEMOGRAPHY ECONOMY RANKINGS SEARCH Esquéhéries Acy FRANCIA Essigny- Agnicourt- le-Grand et-Séchelles Essigny-le-Petit Aguilcourt Essises Aisonville- et-Bernoville Essômes- sur-Marne Aizelles Estrées Aizy-Jouy Étampes- Alaincourt sur-Marne Allemant Étaves- Ambleny et-Bocquiaux Ambrief Étouvelles Amifontaine Étréaupont Amigny-Rouy Étreillers Ancienville Étrépilly Andelain Étreux Anguilcourt- Évergnicourt le-Sart Faverolles Anizy-le-Grand Fayet Annois Fère-en- Any-Martin-Rieux Tardenois Archon Fesmy-le-Sart Arcy-Sainte- Festieux Restitue Fieulaine Armentières- Filain sur-Ourcq Flavigny- Arrancy le-Grand- Artemps et-Beaurain Assis-sur-Serre Flavy-le-Martel Athies- Fleury sous-Laon Fluquières Attilly Folembray Aubencheul- Fonsomme aux-Bois Fontaine- Aubenton lès-Clercs Aubigny- Fontaine- aux-Kaisnes lès-Vervins Aubigny- Fontaine- en-Laonnois Notre-Dame Audignicourt Fontaine-Uterte Audigny Fontenelle Powered by Page 3 Augy Fontenoy L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin Provinces Aulnois- Foreste Adminstat logo sous-Laon -

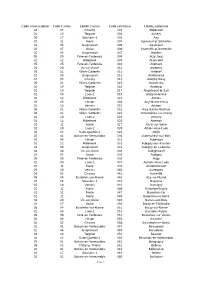

Code Circonscription Code Canton Libellé Canton Code Commune

Code circonscription Code Canton Libellé Canton Code commune Libellé_commune 04 03 Chauny 001 Abbécourt 01 18 Tergnier 002 Achery 05 17 Soissons-2 003 Acy 03 11 Marle 004 Agnicourt-et-Séchelles 01 06 Guignicourt 005 Aguilcourt 03 07 Guise 006 Aisonville-et-Bernoville 01 06 Guignicourt 007 Aizelles 05 05 Fère-en-Tardenois 008 Aizy-Jouy 02 12 Ribemont 009 Alaincourt 05 05 Fère-en-Tardenois 010 Allemant 04 20 Vic-sur-Aisne 011 Ambleny 05 21 Villers-Cotterêts 012 Ambrief 01 06 Guignicourt 013 Amifontaine 04 03 Chauny 014 Amigny-Rouy 05 21 Villers-Cotterêts 015 Ancienville 01 18 Tergnier 016 Andelain 01 18 Tergnier 017 Anguilcourt-le-Sart 01 09 Laon-1 018 Anizy-le-Grand 02 12 Ribemont 019 Annois 03 08 Hirson 020 Any-Martin-Rieux 01 19 Vervins 021 Archon 05 21 Villers-Cotterêts 022 Arcy-Sainte-Restitue 05 21 Villers-Cotterêts 023 Armentières-sur-Ourcq 01 10 Laon-2 024 Arrancy 02 12 Ribemont 025 Artemps 01 11 Marle 027 Assis-sur-Serre 01 10 Laon-2 028 Athies-sous-Laon 02 13 Saint-Quentin-1 029 Attilly 02 01 Bohain-en-Vermandois 030 Aubencheul-aux-Bois 03 08 Hirson 031 Aubenton 02 12 Ribemont 032 Aubigny-aux-Kaisnes 01 06 Guignicourt 033 Aubigny-en-Laonnois 04 20 Vic-sur-Aisne 034 Audignicourt 03 07 Guise 035 Audigny 05 05 Fère-en-Tardenois 036 Augy 01 09 Laon-1 037 Aulnois-sous-Laon 03 11 Marle 039 Autremencourt 03 19 Vervins 040 Autreppes 04 03 Chauny 041 Autreville 05 04 Essômes-sur-Marne 042 Azy-sur-Marne 04 16 Soissons-1 043 Bagneux 03 19 Vervins 044 Bancigny 01 11 Marle 046 Barenton-Bugny 01 11 Marle 047 Barenton-Cel 01 11 Marle 048 Barenton-sur-Serre -

The Late Bandkeramik of the Aisne Valley: Environment and Spatial Organisation

THE LATE BANDKERAMIK OF THE AISNE VALLEY: ENVIRONMENT AND SPATIAL ORGANISATION M. ILETT, C. CONSTANTIN, A. COUDART AND J.P. DEMOULE The river volleys of the Paris Basin provide a rather different geological and topographical context for settlement than the loess regions typically occupied by the Bandkeramik Culture in central and west-central Europe (Modderman 1958/1959; Sielmann 1972; Kruk 1973; Kuper and Lüning 1975; Bakels 1978a). In the Aisne valley (fig. 1) a relatively complete picture of Bandkeramik settlement has emerged as a result of a series of rescue excavations in the 1960s (Boureux and Coudart 1978) and the current Paris University/C.N.R.S. project, founded by the late Bohumil Soudsky shortly after his arrival to teach in Paris in 1971 (F.P.V.A. 1973-1981). This article is mainly concerned with the relationship between the sites and the local environment, and with their dislribution along the valley. A preliminary account will also be given of work in progress on the internal organisation of the settlements. Cultural and chronological background In view of the special nature of settlement dis- tribution in the valley and its relative isolation from centres of Bandkeramik population in the Low Countries and Germany, it is important to underline the originality of the material culture of the Aisne Late Bandkeramik. This introduc- tory section summarises the main characteristics of the ceramics, the lithic industry, and the houseplans. Bonc and antler artifacts have yet to be studied in detail. The excavations at Cuiry-lès-Chaudardes have provided by far the greatest quantity of pottery.