The Late Bandkeramik of the Aisne Valley: Environment and Spatial Organisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CC Du Chemin Des Dames (Siren : 240200592)

Groupement Mise à jour le 01/07/2021 CC du Chemin des Dames (Siren : 240200592) FICHE SIGNALETIQUE BANATIC Données générales Nature juridique Communauté de communes (CC) Commune siège Craonne Arrondissement Laon Département Aisne Interdépartemental non Date de création Date de création 29/12/1995 Date d'effet 29/12/1995 Organe délibérant Mode de répartition des sièges Répartition de droit commun Nom du président M. Jean-Paul COFFINET Coordonnées du siège Complément d'adresse du siège 1 rue de l'Eglise Numéro et libellé dans la voie Distribution spéciale Code postal - Ville 02160 Craonne Téléphone 03 23 22 47 84 Fax 03 23 22 47 84 Courriel [email protected] Site internet www.cc-chemindesdames.fr Profil financier Mode de financement Fiscalité additionnelle sans fiscalité professionnelle de zone et sans fiscalité professionnelle sur les éoliennes Bonification de la DGF non Dotation de solidarité communautaire (DSC) non Taxe d'enlèvement des ordures ménagères (TEOM) non Autre taxe non Redevance d'enlèvement des ordures ménagères (REOM) non Autre redevance non 1/4 Groupement Mise à jour le 01/07/2021 Population Population totale regroupée 5 588 Densité moyenne 31,14 Périmètre Nombre total de communes membres : 30 Dept Commune (N° SIREN) Population 02 Aizelles (210200077) 124 02 Aubigny-en-Laonnois (210200333) 107 02 Beaurieux (210200572) 861 02 Berrieux (210200713) 190 02 Bouconville-Vauclair (210200994) 195 02 Bourg-et-Comin (210201034) 828 02 Braye-en-Laonnois (210201117) 201 02 Chermizy-Ailles (210201653) 108 02 Chevregny (210201703) -

ZRR - Zone De Revitalisation Rurale : Exonération De Cotisations Sociales

ZRR - Zone de Revitalisation Rurale : exonération de cotisations sociales URSSAF Présentation du dispositif Les entreprises en ZRR (Zone de Revitalisation Rurale) peuvent être exonérée des charges patronales lors de l'embauche d'un salarié, sous certaines conditions. Ces conditions sont notamment liées à son effectif, au type de contrat et à son activité. Conditions d'attribution A qui s’adresse le dispositif ? Entreprises éligibles Toute entreprise peut bénéficier d'une exonération de cotisations sociales si elle respecte les conditions suivantes : elle exerce une activité industrielle, commerciale, artisanale, agricole ou libérale, elle a au moins 1 établissement situé en zone de revitalisation rurale (ZRR), elle a 50 salariés maximum. Critères d’éligibilité L'entreprise doit être à jour de ses obligations vis-à-vis de l'Urssaf. L'employeur ne doit pas avoir effectué de licenciement économique durant les 12 mois précédant l'embauche. Pour quel projet ? Dépenses concernées L'exonération de charges patronales porte sur le salarié, à temps plein ou à temps partiel : en CDI, ou en CDD de 12 mois minimum. L'exonération porte sur les assurances sociales : maladie-maternité, invalidité, décès, assurance vieillesse, allocations familiales. URSSAF ZRR - Zone de Revitalisation Rurale : exonération de cotisations sociales Page 1 sur 5 Quelles sont les particularités ? Entreprises inéligibles L'exonération ne concerne pas les particuliers employeurs. Dépenses inéligibles L'exonération de charges ne concerne pas les contrats suivants : CDD qui remplace un salarié absent (ou dont le contrat de travail est suspendu), renouvellement d'un CDD, apprentissage ou contrat de professionnalisation, gérant ou PDG d'une société, employé de maison. -

Liste Communes Par Troncon

LISTE DES COMMUNES CONCERNEES PAR LA VIGILANCE CRUES BASSIN DE L’OISE TRONCON COMMUNES ACHERY MESBRECOURT RICHECOURT AGNICOURT ET SECHELLES MEZIERES-SUR-OISE ALAINCOURT MONCEAU SUR OISE ANGUILCOURT LE SART MONTCORNET ASSIS SUR SERRE MONTIGNY SOUS MARLE AUTREPPES MONTIGNY SUR CRECY BERNOT MONT D’ORIGNY BERTHENICOURT MONDREPUIS BOSMONT SUR SERRE MORTIERS BRISSAY-CHOIGNY MOY-DE-L’AISNE BRISSY-HAMEGICOURT NEUVE-MAISON CHALANDRY NEUVILETTE CHAOURSE NOUVION ET CATILLON CHARMES NOUVION LE COMTE CHATILLON-SUR-OISE NOYALES CHIGNY OHIS CILLY ORIGNY EN THIERACHE COURBES ORIGNY-SAINTE-BENOITE CRECY SUR SERRE POUILLY SUR SERRE DERCY PROISY OISE-AMONT DEUILLET PROIX EFFRY QUIERZY ENGLANCOURT REMIES ERLON RIBEMONT ERLOY ROMERY ETREAUPONT SAINT-ALGIS FLAVIGNY LE GRAND ET BEAURAIN SAINT-PIERREMONT GERGNY SERY-LES-MEZIERES GUISE SISSY HAUTEVILLE SORBAIS HIRSON TAVAUX-PONTSERICOURT LA BOUTEILLE THENELLES LA NEUVILLE-BOSMONT TRAVECY LESQUIELLES SAINT GERMAIN VADENCOURT LUZOIR VENDEUIL MACQUIGNY VOYENNE MALZY WIEGE-FATY MARCY SOUS MARLE WIMY MARLE MARLY-GOMONT MAYOT BASSIN DE L’OISE TRONCON COMMUNES ABBECOURT CHAUNY OGNES AMIGNY-ROUY CONDREN SERVAIS ANDELAIN DANIZY SINCENY OISE MOYENNE AUTREVILLE LA FERE TERGNIER BEAUTOR MANICAMP VIRY NOUREUIL BICHANCOURT MAREST-DAMPCOURT - 25 - BASSIN DE L’AISNE TRONCON COMMUNES ACY MISSY SUR AISNE AMBLENY MONTIGNY-LENGRAIN BEAURIEUX MOUSSY-VERNEUIL BERNY-RIVIERE OEUILLY BERRY-AU-BAC OSLY-COURTIL BOURG-ET-COMIN PARGNAN BUCY LE LONG PASLY CELLES SUR AISNE PERNANT CHASSEMY POMMIERS CHAUDARDES PONT-ARCY CHAVONNE PONTAVERT AISNE -

Supplementary Information for Ancient Genomes from Present-Day France

Supplementary Information for Ancient genomes from present-day France unveil 7,000 years of its demographic history. Samantha Brunel, E. Andrew Bennett, Laurent Cardin, Damien Garraud, Hélène Barrand Emam, Alexandre Beylier, Bruno Boulestin, Fanny Chenal, Elsa Cieselski, Fabien Convertini, Bernard Dedet, Sophie Desenne, Jerôme Dubouloz, Henri Duday, Véronique Fabre, Eric Gailledrat, Muriel Gandelin, Yves Gleize, Sébastien Goepfert, Jean Guilaine, Lamys Hachem, Michael Ilett, François Lambach, Florent Maziere, Bertrand Perrin, Susanne Plouin, Estelle Pinard, Ivan Praud, Isabelle Richard, Vincent Riquier, Réjane Roure, Benoit Sendra, Corinne Thevenet, Sandrine Thiol, Elisabeth Vauquelin, Luc Vergnaud, Thierry Grange, Eva-Maria Geigl, Melanie Pruvost Email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], Contents SI.1 Archaeological context ................................................................................................................. 4 SI.2 Ancient DNA laboratory work ................................................................................................... 20 SI.2.1 Cutting and grinding ............................................................................................................ 20 SI.2.2 DNA extraction .................................................................................................................... 21 SI.2.3 DNA purification ................................................................................................................. 22 SI.2.4 -

Les Continuités Ecologiques Régionales En Hauts-De-France

CHAMBRY Les Continuités Ecologiques MARCHAIS LAPPION Régionales en Hauts-de-France ATHIES-SOUS-LAON SAMOUSSY LA SELVE A1 A2 A3 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 NIZY-LE-COMTE C1 C2 C3 C4 C5 C6 LAON COUCY-LES-EPPES SISSONNE D1 D2 D3 D4 D5 D6 D7 EPPES MONTAIGU E1 E2 E3 E4 E5 E6 E7 F1 F2 F3 F4 F5 F6 F7 G1 G2 G3 G4 G5 G6 PARFONDRU VESLUD H1 H2 H3 H4 H5 H6 LOR I1 I2 I3 I4 MAUREGNY-EN-HAYE FESTIEUX CONTINUITES ECOLOGIQUES SAINT-ERME-OUTRE-ET-RAMECOURT LA MALMAISON COURTRIZY-ET-FUSSIGNY CHERET MONTCHALONS Réservoirs de biodiversité Réservoirs de Biodiversité de la trame bleue (cours d'eau de la liste 2 + réservoirs biologiques des Sdage) ORGEVAL SAINT-THOMAS Réservoirs de Biodiversité de la trame verte AMIFONTAINE ARRANCY AUBIGNY-EN-LAONNOIS Corridors principaux GOUDELANCOURT-LES-BERRIEUX BIEVRESPLOYART-ET-VAURSEINE Corridors boisés MARTIGNY-COURPIERRE Attention: les corridors écologiques, AIZELLES Corridors humides au contraire des réservoirs, ne sont BERRIEUX PROUVAIS pas localisés précisément par le SAINTE-CROIX schéma. Ils doivent être compris PROVISEUX-ET-PLESNOY Corridors littoraux comme des "fonctionnalités écologiques", c'est-à-dire des Corridors ouverts caractéristiques à réunir entre deux réservoirs pour répondre aux besoins des espèces (faune NEUVILLE-SUR-AILETTE Corridors multitrames et flore) et faciliter leurs échanges BOUCONVILLE-VAUCLAIR génétiques et leur dispersion. CORBENY Corridors fluviaux CHERMIZY-AILLES EVERGNICOURT Zones à enjeux CERNY-EN-LAONNOIS JUVINCOURT-ET-DAMARY Zones à enjeu d'identification de corridors bocagers CRAONNE G GUIGNICOURT -

Travaux De Désembâclement De La Rivière Aisne Programme 2 Tranche 3

UNION DES SYNDICATS D’AMENAGEMENT ET DE GESTION DES MILIEUX AQUATIQUES Service technique _______ Syndicat intercommunal pour la gestion du bassin versant de l’Aisne axonaise non navigable et de ses affluents Travaux de désembâclement de la rivière Aisne Programme 2 Tranche 3 _____ Compte-rendu de la réunion de piquetage du 25 septembre 2018 Lieu : Parking place de la mairie de Guignicourt à 9h30 Maître d’ouvrage : Maître d’œuvre : Entreprise : Syndicat intercommunal pour la gestion du bassin versant de l’Aisne Union des Syndicats d’Aménagement et NINO MASCITTI SA axonaise non navigable et de ses de Gestion des Milieux Aquatiques affluents Nom, Prénom: Organisme : Présent Absent Excusé GILET Rémy Président du SIGMAA x DEZUROT Raymond Membre du bureau du SIGMAA x BOMBART Marcel Membre du bureau du SIGMAA x HUCHET William Union des Syndicats de rivières x SCHLOSSER Joël DRIEE Ile de France (service police de l’eau) x DUCAT Philippe Vice-Président de la CCCP x FAVEREAU Gilles Délégué de Condé-sur-Suippe x LEGRAND Colette Délégué de Menneville x ROBERT Alain Délégué de Pignicourt x DEGHAYE Patricia Délégué de Bourg-et-Comin x CARAMELLE Bertrand Maire de Pargnan X RASERO Philippe Délégué de Pontavert X BARBIER Mickael MASCITTI NINO X BOUSSARD François Agence de l’eau Seine-Normandie x • Cette réunion de piquetage concerne les travaux de désembâclement sur la rivière Aisne (tranche 3). Ces travaux ont été confiés, après appel d’offres, à l’entreprise NINO MASCITTI SA – (siège : 6, rue des Bucherons – B.P. 78 – 02 602 VILLERS COTTERETS). 1 SITUATION ACTUELLE : Suite au diagnostic des embâcles réalisé durant le mois de mai 2018, 52 embâcles présentant un risque ont été inventoriés et doivent être traités par l’entreprise. -

Rankings Municipality of Cuiry- Lès-Chaudardes

9/29/2021 Maps, analysis and statistics about the resident population Demographic balance, population and familiy trends, age classes and average age, civil status and foreigners Skip Navigation Links FRANCIA / HAUTS DE FRANCE / Province of AISNE / Cuiry-lès-Chaudardes Powered by Page 1 L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin Adminstat logo DEMOGRAPHY ECONOMY RANKINGS SEARCH FRANCIA Municipalities Powered by Page 2 Abbécourt Stroll up beside >> L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin Erloy AdminstatAchery logo DEMOGRAPHY ECONOMY RANKINGS SEARCH Esquéhéries Acy FRANCIA Essigny- Agnicourt- le-Grand et-Séchelles Essigny-le-Petit Aguilcourt Essises Aisonville- et-Bernoville Essômes- sur-Marne Aizelles Estrées Aizy-Jouy Étampes- Alaincourt sur-Marne Allemant Étaves- Ambleny et-Bocquiaux Ambrief Étouvelles Amifontaine Étréaupont Amigny-Rouy Étreillers Ancienville Étrépilly Andelain Étreux Anguilcourt- Évergnicourt le-Sart Faverolles Anizy-le-Grand Fayet Annois Fère-en- Any-Martin-Rieux Tardenois Archon Fesmy-le-Sart Arcy-Sainte- Festieux Restitue Fieulaine Armentières- Filain sur-Ourcq Flavigny- Arrancy le-Grand- Artemps et-Beaurain Assis-sur-Serre Flavy-le-Martel Athies- Fleury sous-Laon Fluquières Attilly Folembray Aubencheul- Fonsomme aux-Bois Fontaine- Aubenton lès-Clercs Aubigny- Fontaine- aux-Kaisnes lès-Vervins Aubigny- Fontaine- en-Laonnois Notre-Dame Audignicourt Fontaine-Uterte Audigny Fontenelle Powered by Page 3 Augy Fontenoy L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin Provinces Aulnois- Foreste Adminstat logo sous-Laon -

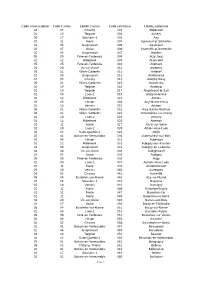

Code Circonscription Code Canton Libellé Canton Code Commune

Code circonscription Code Canton Libellé Canton Code commune Libellé_commune 04 03 Chauny 001 Abbécourt 01 18 Tergnier 002 Achery 05 17 Soissons-2 003 Acy 03 11 Marle 004 Agnicourt-et-Séchelles 01 06 Guignicourt 005 Aguilcourt 03 07 Guise 006 Aisonville-et-Bernoville 01 06 Guignicourt 007 Aizelles 05 05 Fère-en-Tardenois 008 Aizy-Jouy 02 12 Ribemont 009 Alaincourt 05 05 Fère-en-Tardenois 010 Allemant 04 20 Vic-sur-Aisne 011 Ambleny 05 21 Villers-Cotterêts 012 Ambrief 01 06 Guignicourt 013 Amifontaine 04 03 Chauny 014 Amigny-Rouy 05 21 Villers-Cotterêts 015 Ancienville 01 18 Tergnier 016 Andelain 01 18 Tergnier 017 Anguilcourt-le-Sart 01 09 Laon-1 018 Anizy-le-Grand 02 12 Ribemont 019 Annois 03 08 Hirson 020 Any-Martin-Rieux 01 19 Vervins 021 Archon 05 21 Villers-Cotterêts 022 Arcy-Sainte-Restitue 05 21 Villers-Cotterêts 023 Armentières-sur-Ourcq 01 10 Laon-2 024 Arrancy 02 12 Ribemont 025 Artemps 01 11 Marle 027 Assis-sur-Serre 01 10 Laon-2 028 Athies-sous-Laon 02 13 Saint-Quentin-1 029 Attilly 02 01 Bohain-en-Vermandois 030 Aubencheul-aux-Bois 03 08 Hirson 031 Aubenton 02 12 Ribemont 032 Aubigny-aux-Kaisnes 01 06 Guignicourt 033 Aubigny-en-Laonnois 04 20 Vic-sur-Aisne 034 Audignicourt 03 07 Guise 035 Audigny 05 05 Fère-en-Tardenois 036 Augy 01 09 Laon-1 037 Aulnois-sous-Laon 03 11 Marle 039 Autremencourt 03 19 Vervins 040 Autreppes 04 03 Chauny 041 Autreville 05 04 Essômes-sur-Marne 042 Azy-sur-Marne 04 16 Soissons-1 043 Bagneux 03 19 Vervins 044 Bancigny 01 11 Marle 046 Barenton-Bugny 01 11 Marle 047 Barenton-Cel 01 11 Marle 048 Barenton-sur-Serre -

Janvier 1991 R 31956 Cha 4S 91 Societe Zeimett Analyse Du

BRGM L'ENTREPmSI AU SERVICE DE IA TEURE JANVIER 1991 R 31956 CHA 4S 91 SOCIETE ZEIMETT ANALYSE DU CONTEXTE HYDROGEOLOGIQUE DU PROJCT D'EXPLOITATION DES ALLUVIONS ANCIENNES A CUIRY-LES-CHAUDARDES JN. HATRIVAL BRGM - CHAMPAGNE-ARDENNE 13, boulevard Général-Leclerc - 51100 Reime, France Tél.: ;33¡ 26.47.93.40 - Télécopieur : (33) 26.40.1 3.64 SOMMAIRE Pages INTRODUCTION 1 I. SITUATION 2 II. CONTEXTE GEOLOGIQUE 2 III. ETUDE DU SITE 5 1. CARTE DE LA BASE DES GRAVIERS 5 2. CARTE PIEZOMETRIQUE EN PERIODE D'ETIAGE 5 3. CARTE DU TERRAIN NATUREL 9 4. INCIDENCE DU PLAN D'EAU SUR LA PIEZOMETRIE 9 5. SURCREUSEMENT 9 IV. CONCLUSIONS 14 LISTE DES FIGURES Figure 1 : Plan de situation Figure 2 : Sondage de référence Figure 3 : Carte de la base des graviers Figure 4 : Carte piézométrique en période d'étiage Figure 5 : Carte du terrain naturel Figure 6 : Carte piézométrique avant l'exploitation Figure 7 : Carte piézométrique après l'exploitation Figure 8 : Carte d'appronfondissement Figure 9 : Carte des zones exondées Annexes de 1 à 7 : Coupes des sondages à la pelle mécanique 1 INTRODUCTION L'entreprise ZEIMETT MATERIAUX a prévu d'exploiter les graviers des alluvions de l'Aisne, sur les communes de CUIRY-LES- CHAUDARDES et de BEAURIEUX, aux lieu-dits "La plaine" et "La Haute Borne". Le projet de réaménagement final prévoit : ou bien l'instal lation d'un plan d'eau, ou bien une remise en état des terrains pour une reprise de l'exploitation agricole. Devant les anomalies apparues dans les niveaux de la nappe alluviale, la Société ZEIMETT a confié au BRGM (Agence Champagne- Ardenne) une analyse du contexte hydrogéologique local afin d'orienter le programme de réaménagement de l'entreprise. -

Télécharger La Carte

Fesmy-le-Sart St-Martin- Barzy-en- Rivière Thiérache Ribeauville Molain Bergues- Fontenelle La sur-Sambre Rocquigny Vallée- Oisy Aubencheul- Serain Mulâtre aux-Bois Wassigny Papleux Becquigny Prémont Boué Vaux-Andigny LeNouvion-en-Thiérache Vendhuile LaFlamengrie Gouy Vénérolles Etreux LeCatelet Beaurevoir Lempire La Bohain-en-Vermandois Mennevret Bony Neuville- lès-Dorengt Esquéhéries Hannapes Clairfontaine Brancourt- LaCapelle le-Grand Estrées Tupigny Mondrepuis Montbrehain Dorengt Hargicourt Leschelles Sommeron Petit- Buironfosse Bellicourt Ramicourt Seboncourt Verly Lerzy Joncourt Fresnoy-le-Grand Iron Wimy Hirson Nauroy Grougis Lavaqueresse Froidestrées Villeret Grand- Verly Sequehart Gergny Magny- Aisonville- Crupilly Neuve- la-Fosse Levergies Croix- Etaves- Lesquielles- Chigny Luzoir Maison Fonsommes et-Bernoville St-Germain Villers- St-Michel et-Bocquiaux Englancourt Pontru CompagnieFontaine- de lès-Guise CompagnieBellenglise de Ef ry Vadencourt Malzy Ohis Jeancourt Le Uterte Erloy Sorbais Verguier Montigny- Lehaucourt Buire Watigny en- Noyales Monceau- Pontruet Arrouaise sur-Oise Vendelles Essigny- Fonsommes Compagnie de Fieulaine Compagnie de Lesdins le-Petit Proix Autreppes Guise St-Algis Origny- Flavigny- Proisy Marly-Gomont Etréaupont Saint-QuentinRemaucourt en- Eparcy Saint-QuentinHauteville Maissemy le-Grand- Wiège- La Thiérache Gricourt et-Beaurain Faty Romery LaBouteille Hérie Any-Martin-Rieux Vermand Omissy Bernot Bucilly Morcourt Fontaine- Macquigny Haution Vervins Vervins Martigny Fayet Notre-Dame Audigny Leuze LeSourd -

Degruyter Opar Opar-2020-0160 631..644 ++

Open Archaeology 2021; 7: 631–644 Research Article Pierre Allard*, Caroline Hamon, Louise Gomart Mineral Resources, Procurement Strategies, and Territories in the Linear Pottery Culture in the Aisne Valley (Paris Basin, France) https://doi.org/10.1515/opar-2020-0160 received February 23, 2021; accepted June 16, 2021 Abstract: This article presents the mineral resource procurement territories of Early Neolithic settlements (LBK or Rubané) in the Aisne valley. Our study focuses on data from 15 LBK sites belonging to the final LBK of central Europe; C14 dates for the sites fall between 5100 and 4900 cal BC. The bulk of pottery from these sites seems to have been produced using local raw materials that can be found over a large part of the valley; only a dozen recorded vessels were made of an exogeneous raw material. Analysis of the supply and management of sandstone and flint productions indicates the presence of three groups of villages. These distinct groups correspond to the definition of a cluster as proposed to define site organization in the Aisne valley. On the LBK sites of the Aisne valley blades, polished tools and certain personal ornaments were occasionally made of non-local materials. Some of these objects seem to indicate contacts outside the LBK settlement zones and suggest relationships with southern Neolithic groups. Keywords: LBK, Early Neolithic, raw material, settlement, procurement 1 Introduction The emergence of sedentary lifestyles during the Neolithic transition profoundly modified the relationship of humans to their environment and their raw material procurement strategies. Fertile agricultural envir- onments do not always provide the materials necessary for all components of the technical system and access to geo-resources was no longer integrated within the mobility cycles of nomadic populations (Binder & Perlès, 1990). -

DDFIP Présentation Du Dispositif

ZAI - Zone d'Aide à l'Investissement des PME : Exonération de la CFE DDFIP Présentation du dispositif Les PME peuvent bénéficier d'une exonération de cotisation foncière des entreprises (CFE) lorsqu'elles sont situées dans les communes classées en zone d'aide à l'investissement (ZAI). La cotisation foncière des entreprises (CFE) est l'une des 2 composantes de la contribution économique territoriale (CET) avec la cotisation sur la valeur ajoutée des entreprises (CVAE). La CFE est basée uniquement sur les biens soumis à la taxe foncière. Cette taxe est due dans chaque commune où l'entreprise dispose de locaux et de terrains. Ce dispositif d'exonération s'applique jusqu'au 31/12/2021. Conditions d'attribution A qui s’adresse le dispositif ? Entreprises éligibles Sont éligibles les PME, ayant employé moins de 250 salariés au cours de la période d'exonération et ayant réalisé un chiffre d'affaires inférieur à 50 M€. Critères d’éligibilité Les PME doivent procéder à : une extension ou création d'activité industrielle ou de recherche scientifique et technique, ou de services de direction, d'études, d'ingénierie et d'informatique, une reconversion dans le même type d'activités, la reprise d'établissements en difficulté exerçant le même type d'activité. Quelles sont les particularités ? Les zones d'aide à l'investissement des PME correspondent aux communes ou parties de communes qui ne sont pas classées en zone d'aide à finalité régionale. Montant de l'aide De quel type d’aide s’agit-il ? DDFIP ZAI - Zone d'Aide à l'Investissement des PME : Exonération de la CFE Page 1 sur 6 L'exonération de cotisation foncière des entreprises peut être totale ou partielle selon la délibération de la commune ou de l'établissement public de coopération intercommunale (EPCI).