Arxiv:1910.00666V1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The X-Ray Universe 2017

The X-ray Universe 2017 6−9 June 2017 Centro Congressi Frentani Rome, Italy A conference organised by the European Space Agency XMM-Newton Science Operations Centre National Institute for Astrophysics, Italian Space Agency University Roma Tre, La Sapienza University ABSTRACT BOOK Oral Communications and Posters Edited by Simone Migliari, Jan-Uwe Ness Organising Committees Scientific Organising Committee M. Arnaud Commissariat ´al’´energie atomique Saclay, Gif sur Yvette, France D. Barret (chair) Institut de Recherche en Astrophysique et Plan´etologie, France G. Branduardi-Raymont Mullard Space Science Laboratory, Dorking, Surrey, United Kingdom L. Brenneman Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, Cambridge, USA M. Brusa Universit`adi Bologna, Italy M. Cappi Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica, Bologna, Italy E. Churazov Max-Planck-Institut f¨urAstrophysik, Garching, Germany A. Decourchelle Commissariat ´al’´energie atomique Saclay, Gif sur Yvette, France N. Degenaar University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands A. Fabian University of Cambridge, United Kingdom F. Fiore Osservatorio Astronomico di Roma, Monteporzio Catone, Italy F. Harrison California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, USA M. Hernanz Institute of Space Sciences (CSIC-IEEC), Barcelona, Spain A. Hornschemeier Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, USA V. Karas Academy of Sciences, Prague, Czech Republic C. Kouveliotou George Washington University, Washington DC, USA G. Matt Universit`adegli Studi Roma Tre, Roma, Italy Y. Naz´e Universit´ede Li`ege, Belgium T. Ohashi Tokyo Metropolitan University, Japan I. Papadakis University of Crete, Heraklion, Greece J. Hjorth University of Copenhagen, Denmark K. Poppenhaeger Queen’s University Belfast, United Kingdom N. Rea Instituto de Ciencias del Espacio (CSIC-IEEC), Spain T. Reiprich Bonn University, Germany M. Salvato Max-Planck-Institut f¨urextraterrestrische Physik, Garching, Germany N. -

The Birth of Stars and Planets

Unit 6: The Birth of Stars and Planets This material was developed by the Friends of the Dominion Astrophysical Observatory with the assistance of a Natural Science and Engineering Research Council PromoScience grant and the NRC. It is a part of a larger project to present grade-appropriate material that matches 2020 curriculum requirements to help students understand planets, with a focus on exoplanets. This material is aimed at BC Grade 6 students. French versions are available. Instructions for teachers ● For questions and to give feedback contact: Calvin Schmidt [email protected], ● All units build towards the Big Idea in the curriculum showing our solar system in the context of the Milky Way and the Universe, and provide background for understanding exoplanets. ● Look for Ideas for extending this section, Resources, and Review and discussion questions at the end of each topic in this Unit. These should give more background on each subject and spark further classroom ideas. We would be happy to help you expand on each topic and develop your own ideas for your students. Contact us at the [email protected]. Instructions for students ● If there are parts of this unit that you find confusing, please contact us at [email protected] for help. ● We recommend you do a few sections at a time. We have provided links to learn more about each topic. ● You don’t have to do the sections in order, but we recommend that. Do sections you find interesting first and come back and do more at another time. ● It is helpful to try the activities rather than just read them. -

September 2020 BRAS Newsletter

A Neowise Comet 2020, photo by Ralf Rohner of Skypointer Photography Monthly Meeting September 14th at 7:00 PM, via Jitsi (Monthly meetings are on 2nd Mondays at Highland Road Park Observatory, temporarily during quarantine at meet.jit.si/BRASMeets). GUEST SPEAKER: NASA Michoud Assembly Facility Director, Robert Champion What's In This Issue? President’s Message Secretary's Summary Business Meeting Minutes Outreach Report Asteroid and Comet News Light Pollution Committee Report Globe at Night Member’s Corner –My Quest For A Dark Place, by Chris Carlton Astro-Photos by BRAS Members Messages from the HRPO REMOTE DISCUSSION Solar Viewing Plus Night Mercurian Elongation Spooky Sensation Great Martian Opposition Observing Notes: Aquila – The Eagle Like this newsletter? See PAST ISSUES online back to 2009 Visit us on Facebook – Baton Rouge Astronomical Society Baton Rouge Astronomical Society Newsletter, Night Visions Page 2 of 27 September 2020 President’s Message Welcome to September. You may have noticed that this newsletter is showing up a little bit later than usual, and it’s for good reason: release of the newsletter will now happen after the monthly business meeting so that we can have a chance to keep everybody up to date on the latest information. Sometimes, this will mean the newsletter shows up a couple of days late. But, the upshot is that you’ll now be able to see what we discussed at the recent business meeting and have time to digest it before our general meeting in case you want to give some feedback. Now that we’re on the new format, business meetings (and the oft neglected Light Pollution Committee Meeting), are going to start being open to all members of the club again by simply joining up in the respective chat rooms the Wednesday before the first Monday of the month—which I encourage people to do, especially if you have some ideas you want to see the club put into action. -

How Supernovae Became the Basis of Observational Cosmology

Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, 19(2), 203–215 (2016). HOW SUPERNOVAE BECAME THE BASIS OF OBSERVATIONAL COSMOLOGY Maria Victorovna Pruzhinskaya Laboratoire de Physique Corpusculaire, Université Clermont Auvergne, Université Blaise Pascal, CNRS/IN2P3, Clermont-Ferrand, France; and Sternberg Astronomical Institute of Lomonosov Moscow State University, 119991, Moscow, Universitetsky prospect 13, Russia. Email: [email protected] and Sergey Mikhailovich Lisakov Laboratoire Lagrange, UMR7293, Université Nice Sophia-Antipolis, Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur, Boulevard de l'Observatoire, CS 34229, Nice, France. Email: [email protected] Abstract: This paper is dedicated to the discovery of one of the most important relationships in supernova cosmology—the relation between the peak luminosity of Type Ia supernovae and their luminosity decline rate after maximum light. The history of this relationship is quite long and interesting. The relationship was independently discovered by the American statistician and astronomer Bert Woodard Rust and the Soviet astronomer Yury Pavlovich Pskovskii in the 1970s. Using a limited sample of Type I supernovae they were able to show that the brighter the supernova is, the slower its luminosity declines after maximum. Only with the appearance of CCD cameras could Mark Phillips re-inspect this relationship on a new level of accuracy using a better sample of supernovae. His investigations confirmed the idea proposed earlier by Rust and Pskovskii. Keywords: supernovae, Pskovskii, Rust 1 INTRODUCTION However, from the moment that Albert Einstein (1879–1955; Whittaker, 1955) introduced into the In 1998–1999 astronomers discovered the accel- equations of the General Theory of Relativity a erating expansion of the Universe through the cosmological constant until the discovery of the observations of very far standard candles (for accelerating expansion of the Universe, nearly a review see Lipunov and Chernin, 2012). -

Download This Issue (Pdf)

Volume 46 Number 2 JAAVSO 2018 The Journal of the American Association of Variable Star Observers Unmanned Aerial Systems for Variable Star Astronomical Observations The NASA Altair UAV in flight. Also in this issue... • A Study of Pulsation and Fadings in some R CrB Stars • Photometry and Light Curve Modeling of HO Psc and V535 Peg • Singular Spectrum Analysis: S Per and RZ Cas • New Observations, Period and Classification of V552 Cas • Photometry of Fifteen New Variable Sources Discovered by IMSNG Complete table of contents inside... The American Association of Variable Star Observers 49 Bay State Road, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA The Journal of the American Association of Variable Star Observers Editor John R. Percy Laszlo L. Kiss Ulisse Munari Dunlap Institute of Astronomy Konkoly Observatory INAF/Astronomical Observatory and Astrophysics Budapest, Hungary of Padua and University of Toronto Asiago, Italy Toronto, Ontario, Canada Katrien Kolenberg Universities of Antwerp Karen Pollard Associate Editor and of Leuven, Belgium Director, Mt. John Observatory Elizabeth O. Waagen and Harvard-Smithsonian Center University of Canterbury for Astrophysics Christchurch, New Zealand Production Editor Cambridge, Massachusetts Michael Saladyga Nikolaus Vogt Kristine Larsen Universidad de Valparaiso Department of Geological Sciences, Valparaiso, Chile Editorial Board Central Connecticut State Geoffrey C. Clayton University, Louisiana State University New Britain, Connecticut Baton Rouge, Louisiana Vanessa McBride Kosmas Gazeas IAU Office of Astronomy for University of Athens Development; South African Athens, Greece Astronomical Observatory; and University of Cape Town, South Africa The Council of the American Association of Variable Star Observers 2017–2018 Director Stella Kafka President Kristine Larsen Past President Jennifer L. -

Cosmic Times Teachers' Guide Table of Contents

Cosmic Times Teachers’ Guide Table of Contents Cosmic Times Teachers’ Guide ....................................................................................... 1 1919 Cosmic Times ........................................................................................................... 3 Summary of the 1919 Articles...................................................................................................4 Sun’s Gravity Bends Starlight .................................................................................................4 Sidebar: Why a Total Eclipse?.................................................................................................4 Mount Wilson Astronomer Estimates Milky Way Ten Times Bigger Than Thought ............4 Expanding or Contracting? ......................................................................................................4 In Their Own Words................................................................................................................4 Notes on the 1919 Articles .........................................................................................................5 Sun's Gravity Bends Starlight..................................................................................................5 Sidebar: Why a Total Eclipse?.................................................................................................7 Mount Wilson Astronomer Estimates Milky Way Ten Times Bigger Than Thought ............7 Expanding or Contracting? ......................................................................................................8 -

Making a Sky Atlas

Appendix A Making a Sky Atlas Although a number of very advanced sky atlases are now available in print, none is likely to be ideal for any given task. Published atlases will probably have too few or too many guide stars, too few or too many deep-sky objects plotted in them, wrong- size charts, etc. I found that with MegaStar I could design and make, specifically for my survey, a “just right” personalized atlas. My atlas consists of 108 charts, each about twenty square degrees in size, with guide stars down to magnitude 8.9. I used only the northernmost 78 charts, since I observed the sky only down to –35°. On the charts I plotted only the objects I wanted to observe. In addition I made enlargements of small, overcrowded areas (“quad charts”) as well as separate large-scale charts for the Virgo Galaxy Cluster, the latter with guide stars down to magnitude 11.4. I put the charts in plastic sheet protectors in a three-ring binder, taking them out and plac- ing them on my telescope mount’s clipboard as needed. To find an object I would use the 35 mm finder (except in the Virgo Cluster, where I used the 60 mm as the finder) to point the ensemble of telescopes at the indicated spot among the guide stars. If the object was not seen in the 35 mm, as it usually was not, I would then look in the larger telescopes. If the object was not immediately visible even in the primary telescope – a not uncommon occur- rence due to inexact initial pointing – I would then scan around for it. -

Curtis/Shapley Debate – 1920 (This Text Is Taken from the Web –

Curtis/Shapley Debate – 1920 (this text is taken from the Web – http://antwrp.gsfc.nasa.gov/diamond_jubilee/debate20.html) A Mediocre Discussion? “The Size and Shape of the Galaxy/Cosmos And the Existence of other Galaxies” Does it really matter that two astronomers debated each other in the beginning of the 20th century? It is now clear that a once little heard-of discussion was at the crux of a major change of humanity's view of our place in the universe. The events that happened in the first quarter of our century were together much more than a debate - this is a story of hu- manity's discovery of the vastness of our universe, a story of a seemingly small academic disagreement whose dramatic resolution staggered the world. It is a story of human drama - two champion astronomers struggling at the focus of a raging controversy whose solution represents an inspiring synthesis of old and new ideas. It is the story of monumen- tal insight and tragic error. It is a story of an astronomical legend. Does this sound melodramatic? It s all true. And it happened this century. In 1920 Harlow Shapley was a young ambitious astronomer. He had published a series of papers marking several fas- cinating astronomical discoveries - many times involving properties of stars in binary systems or globular clusters. He was a rising star himself - a golden boy of astronomy. In 1920 Heber D. Curtis was a bit older, more established, and very well respected in his own right. He had published a series of solid papers on good astronomical results - many times on the properties of spiral nebulae. -

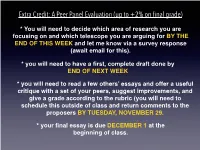

Extra Credit: a Peer Panel Evaluation (Up to +2% on Final Grade)

Extra Credit: A Peer Panel Evaluation (up to +2% on final grade) * You will need to decide which area of research you are focusing on and which telescope you are arguing for BY THE END OF THIS WEEK and let me know via a survey response (await email for this). * you will need to have a first, complete draft done by END OF NEXT WEEK * you will need to read a few others’ essays and offer a useful critique with a set of your peers, suggest improvements, and give a grade according to the rubric (you will need to schedule this outside of class and return comments to the proposers BY TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 29. * your final essay is due DECEMBER 1 at the beginning of class. THE DRAKE EQUATION. ARE WE ALONE? ARE WE ALONE? How many sun-like stars (with planets) have a planet in the habitable zone? Petigura et al. (2013) How many sun-like stars (with planets) have a planet in the habitable zone? Petigura et al. (2013) We didn’t have any clue until Kepler came along, just a few years ago. The best current estimate is that 20+10% of all sun-like stars have planets in their habitable zones. The Kepler Orrery: the incredible diversity of planetary systems. Shout out to Dan Fabrycky! The Kepler Orrery: the incredible diversity of planetary systems. Shout out to Dan Fabrycky! Time to zoom WAYYYY out… Time to zoom WAYYYY out… To do that, we better know how to measure distances to things well. “We are probably nearing the limit of all we can know about astronomy.” -1888 Simon Newcomb “We are probably nearing the limit of all we can know about astronomy.” -1888 “Flight by machines heavier than air is unpractical and insignificant, if not utterly impossible.” -1902 Simon Newcomb We already know a few ways of measuring distances… But that’s it so far! Or is it? We already know a few ways of measuring distances… 2. -

The 22 Month Swift-Bat All-Sky Hard X-Ray Survey

The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 186:378–405, 2010 February doi:10.1088/0067-0049/186/2/378 C 2010. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. THE 22 MONTH SWIFT-BAT ALL-SKY HARD X-RAY SURVEY J. Tueller1, W. H. Baumgartner1,2,3, C. B. Markwardt1,3,4,G.K.Skinner1,3,4, R. F. Mushotzky1, M. Ajello5, S. Barthelmy1, A. Beardmore6, W. N. Brandt7, D. Burrows7, G. Chincarini8, S. Campana8, J. Cummings1, G. Cusumano9, P. Evans6, E. Fenimore10, N. Gehrels1, O. Godet6,D.Grupe7, S. Holland1,3,J.Kennea7,H.A.Krimm1,3,M.Koss1,3,4, A. Moretti8, K. Mukai1,2,3, J. P. Osborne6, T. Okajima1,11, C. Pagani7, K. Page6, D. Palmer10, A. Parsons1, D. P. Schneider7, T. Sakamoto1,12, R. Sambruna1, G. Sato13, M. Stamatikos1,12, M. Stroh7, T. Ukwata1,14, and L. Winter15 1 NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center, Astrophysics Science Division, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA; [email protected] 2 Joint Center for Astrophysics, University of Maryland-Baltimore County, Baltimore, MD 21250, USA 3 CRESST/ Center for Research and Exploration in Space Science and Technology, 10211 Wincopin Circle, Suite 500, Columbia, MD 21044, USA 4 Department of Astronomy, University of Maryland College Park, College Park, MD 20742, USA 5 SLAC National Laboratory and Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology, 2575 Sand Hill Road, Menlo Park, CA 94025, USA 6 X-ray and Observational Astronomy Group/Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Leicester, Leicester, LE1 7RH, UK 7 Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics, Pennsylvania -

Cosmology for Everyone

Cosmology for Everyone http://cdn.spacetelescope.org/archives/images/wallpaper5/hubble_in_orbit1.jpg Dr. Steven Ball Professor of Physics LeTourneau University Hubble Telescope eXtreme Deep Field Modern Cosmology Begins ■ Albert Einstein (1879-1955) ■ Special Relativity (1905) ■ General Relativity (1915): matter-energy <=> space-time www.universetoday.com/56612/einsteins-general- relativity-tested-again-much-more-stringently/ www.science4all.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Gravity.jpg Philosophical Bias to expect ■ Contrast to Newtonian Gravity, static cosmos (unchanging) objects follow curvature of space Had to modify equations to induced by matter yield static cosmos solution Expanding Universe ■ Alexander Friedmann (1888-1925) ■ Solved Einstein’s Field Equations (correcting algebraic mistake and eliminating cosmological constant) ■ Predicted expanding universe from 3 solutions: open (expands forever), closed (will collapse), and flat Size of universe en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Aleksandr_Fridman.png Time Great Debate of 1920 ■ Astronomers Harlow Shapley vs. Heber Curtis ■ Are the spiral nebulae part of the Milky Way Galaxy or island universes far beyond the Milky Way? ■ Inconclusive debate due to lack of observational evidence. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Andromeda_Galaxy_(with_h-alpha).jpg Expanding Universe Confirmed ■ Edwin Hubble (1889-1953) ■ Using Mt. Wilson Observatory 100 inch reflector telescope (1920) ■ By 1925 confirmed that the Andromeda nebula lies far beyond the Milky Way and is also a vast galaxy of stars ■ There are billions of galaxies stretching out in space billions of light years away from us. ■ By 1929 confirmed that the further a galaxy is from us, the faster it recedes from us. www.tumblr.com/search/mount+wilson+observatory Hubble’s Law ■ Expansion of Universe seen in slight change in wavelengths of spectral lines in receding galaxies (redshift z = Δλ/λ) ■ Hubble’s Law: Recesion Velocity = Constant times Distance (v = H d) en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Redshift.png Using present data we now know Ho = 72±1 km/s/Mpc. -

6. the Great Debate: the Solar System's Place in the Galaxy

6. THE GREAT DEBATE: THE SOLAR SYSTEM’S PLACE IN THE GALAXY AND THE GALAXY’S PLACE IN THE UNIVERSE I EQUIPMENT Computer with internet connection GOALS In this lab, you will learn: 1. How to use RR Lyrae variable stars in globular clusters to measure our distance from the center of the Milky Way galaxy (i.e., is the solar system at the center of the Milky Way?) 2. How to use RR Lyrae variable stars in globular clusters to measure the approximate size of the Milky Way. 3. How to use Cepheid variable stars in nearby galaxies to measure their sizes (i.e., is the Milky Way the primary object in the universe or is it merely one of countless many similar-sized objects in the universe?) 1 BACKGROUND A. THE GREAT DEBATE On April 26, 1920, astronomers Harlow Shapley (left) and Heber Curtis (right) debated the size of the then-known universe and our place in it at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History in Washington, DC, in an event that later became known as the Great Debate. Curtis argued that the solar system is near or at the center of the Milky Way galaxy, and that the Milky Way is about 10 kpc across. Shapley, on the other hand, argued that the solar system is in the outskirts of the Milky Way, and that the Milky Way is about 100 kpc across. In section A of the procedure, you will use RR Lyrae variable stars in globular clusters to measure (1) our distance from the center of the Milky Way, and (2) the approximate size of the Milky Way.