Dissertation (S. Pepper)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Same Breath

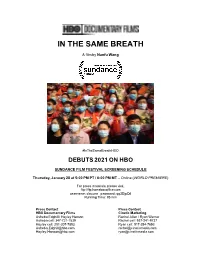

IN THE SAME BREATH A film by Nanfu Wang #InTheSameBreathHBO DEBUTS 2021 ON HBO SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL SCREENING SCHEDULE Thursday, January 28 at 5:00 PM PT / 6:00 PM MT – Online (WORLD PREMIERE) For press materials, please visit: ftp://ftp.homeboxoffice.com username: documr password: qq3DjpQ4 Running Time: 95 min Press Contact Press Contact HBO Documentary Films Cinetic Marketing Asheba Edghill / Hayley Hanson Rachel Allen / Ryan Werner Asheba cell: 347-721-1539 Rachel cell: 937-241-9737 Hayley cell: 201-207-7853 Ryan cell: 917-254-7653 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] LOGLINE Nanfu Wang's deeply personal IN THE SAME BREATH recounts the origin and spread of the novel coronavirus from the earliest days of the outbreak in Wuhan to its rampage across the United States. SHORT SYNOPSIS IN THE SAME BREATH, directed by Nanfu Wang (“One Child Nation”), recounts the origin and spread of the novel coronavirus from the earliest days of the outbreak in Wuhan to its rampage across the United States. In a deeply personal approach, Wang, who was born in China and now lives in the United States, explores the parallel campaigns of misinformation waged by leadership and the devastating impact on citizens of both countries. Emotional first-hand accounts and startling, on-the-ground footage weave a revelatory picture of cover-ups and misinformation while also highlighting the strength and resilience of the healthcare workers, activists and family members who risked everything to communicate the truth. DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT I spent a lot of my childhood in hospitals taking care of my father, who had rheumatic heart disease. -

HBO and the HOLOCAUST: CONSPIRACY, the HISTORICAL FILM, and PUBLIC HISTORY at WANNSEE Nicholas K. Johnson Submitted to the Facul

HBO AND THE HOLOCAUST: CONSPIRACY, THE HISTORICAL FILM, AND PUBLIC HISTORY AT WANNSEE Nicholas K. Johnson Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of History, Indiana University December 2016 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Master’s Thesis Committee __________________________________ Raymond J. Haberski, Ph.D., Chair __________________________________ Thorsten Carstensen, Ph.D. __________________________________ Kevin Cramer, Ph.D. ii Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank the members of my committee for supporting this project and offering indispensable feedback and criticism. I would especially like to thank my chair, Ray Haberski, for being one of the most encouraging advisers I have ever had the pleasure of working with and for sharing his passion for film and history with me. Thorsten Carstensen provided his fantastic editorial skills and for all the times we met for lunch during my last year at IUPUI. I would like to thank Kevin Cramer for awakening my interest in German history and for all of his support throughout my academic career. Furthermore, I would like to thank Jason M. Kelly, Claudia Grossmann, Anita Morgan, Rebecca K. Shrum, Stephanie Rowe, Modupe Labode, Nancy Robertson, and Philip V. Scarpino for all the ways in which they helped me during my graduate career at IUPUI. I also thank the IUPUI Public History Program for admitting a Germanist into the Program and seeing what would happen. I think the experiment paid off. -

Famous Chicagoans Source: Chicago Municipal Library

DePaul Center for Urban Education Chicago Math Connections This project is funded by the Illinois Board of Higher Education through the Dwight D. Eisenhower Professional Development Program. Teaching/Learning Data Bank Useful information to connect math to science and social studies Topic: Famous Chicagoans Source: Chicago Municipal Library Name Profession Nelson Algren author Joan Allen actor Gillian Anderson actor Lorenz Tate actor Kyle actor Ernie Banks, (former Chicago Cub) baseball Jennifer Beals actor Saul Bellow author Jim Belushi actor Marlon Brando actor Gwendolyn Brooks poet Dick Butkus football-Chicago Bear Harry Caray sports announcer Nat "King" Cole singer Da – Brat singer R – Kelly singer Crucial Conflict singers Twista singer Casper singer Suzanne Douglas Editor Carl Thomas singer Billy Corgan musician Cindy Crawford model Joan Cusack actor John Cusack actor Walt Disney animator Mike Ditka football-former Bear's Coach Theodore Dreiser author Roger Ebert film critic Dennis Farina actor Dennis Franz actor F. Gary Gray directory Bob Green sports writer Buddy Guy blues musician Daryl Hannah actor Anne Heche actor Ernest Hemingway author John Hughes director Jesse Jackson activist Helmut Jahn architect Michael Jordan basketball-Chicago Bulls Ray Kroc founder of McDonald's Irv Kupcinet newspaper columnist Ramsey Lewis jazz musician John Mahoney actor John Malkovich actor David Mamet playwright Joe Mantegna actor Marlee Matlin actor Jenny McCarthy TV personality Laurie Metcalf actor Dermot Muroney actor Bill Murray actor Bob Newhart -

Conor Mcpherson 88 Min., 1.85:1, 35Mm

Mongrel Media Presents THE ECLIPSE A film by Conor McPherson 88 min., 1.85:1, 35mm (88min., Ireland, 2009) www.theeclipsefilm.com Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith 1028 Queen Street West Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html SYNOPSIS THE ECLIPSE tells the story of Michael Farr (Ciarán Hinds), a teacher raising his two kids alone since his wife died two years earlier. Lately he has been seeing and hearing strange things late at night in his house. He isn't sure if he is simply having terrifying nightmares or if his house is haunted. Each year, the seaside town where Michael lives hosts an international literary festival, attracting writers from all over the world. Michael works as a volunteer for the festival and is assigned the attractive Lena Morelle (Iben Hjejle), an author of books about ghosts and the supernatural, to look after. They become friendly and he eagerly tells her of his experiences. For the first time he has met someone who can accept the reality of what has been happening to him. However, Lena’s attention is pulled elsewhere. She has come to the festival at the bidding of world-renowned novelist Nicholas Holden (Aidan Quinn), with whom she had a brief affair the previous year. He has fallen in love with Lena and is going through a turbulent time, eager to leave his wife to be with her. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents PART I. Introduction 5 A. Overview 5 B. Historical Background 6 PART II. The Study 16 A. Background 16 B. Independence 18 C. The Scope of the Monitoring 19 D. Methodology 23 1. Rationale and Definitions of Violence 23 2. The Monitoring Process 25 3. The Weekly Meetings 26 4. Criteria 27 E. Operating Premises and Stipulations 32 PART III. Findings in Broadcast Network Television 39 A. Prime Time Series 40 1. Programs with Frequent Issues 41 2. Programs with Occasional Issues 49 3. Interesting Violence Issues in Prime Time Series 54 4. Programs that Deal with Violence Well 58 B. Made for Television Movies and Mini-Series 61 1. Leading Examples of MOWs and Mini-Series that Raised Concerns 62 2. Other Titles Raising Concerns about Violence 67 3. Issues Raised by Made-for-Television Movies and Mini-Series 68 C. Theatrical Motion Pictures on Broadcast Network Television 71 1. Theatrical Films that Raise Concerns 74 2. Additional Theatrical Films that Raise Concerns 80 3. Issues Arising out of Theatrical Films on Television 81 D. On-Air Promotions, Previews, Recaps, Teasers and Advertisements 84 E. Children’s Television on the Broadcast Networks 94 PART IV. Findings in Other Television Media 102 A. Local Independent Television Programming and Syndication 104 B. Public Television 111 C. Cable Television 114 1. Home Box Office (HBO) 116 2. Showtime 119 3. The Disney Channel 123 4. Nickelodeon 124 5. Music Television (MTV) 125 6. TBS (The Atlanta Superstation) 126 7. The USA Network 129 8. Turner Network Television (TNT) 130 D. -

How “When They See Us” and “Chernobyl” Make Us Look These New True-Story Series Manage to Make Depressing, Traumatic Material Not Merely Watchable but Mesmerizing

How “When They See Us” and “Chernobyl” Make Us Look These new true-story series manage to make depressing, traumatic material not merely watchable but mesmerizing. By Emily Nussbaum The New Yorker, June 17, 2019 https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/06/24/how- when-they-see-us-and-chernobyl-make-us-look In the third episode of “When They See Us,” Ava DuVernay’s bleak, beautiful drama about the Central Park Five, Linda McCray (Marsha Stephanie Blake) visits her son Antron in a juvenile-detention center. “I feel like everybody in the world hate me, Mom,” Antron (Caleel Harris) tells her. “I know it feels like that,” she says, then adds, fiercely, “But I love you enough to make up for everybody.” As music rises, Linda tells her son that she is always with him: “You cry, I cry. You mad, I’m mad. You scared, I’m scared. You free, I’m free.” The camera cuts to autumn leaves—and to the day of Antron’s release from prison, seven years later, as the child actor is replaced by a handsome adult, embracing his mother. “Hi, baby,” Linda says. It’s an elegant, affecting sequence—at once grand and simple, movingly performed— which captures the central ethos of the show. “When They See Us,” on Netflix, is a harrowing story about a hideous injustice: the railroading of a group of five black and Latino boys for the beating and rape of Trisha Meili, who was attacked while jogging in Central Park, in 1989. The show portrays a racist justice system and an equally hellish penal system, as well as media that amplified the lies that put the boys in prison. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1982

Nat]onal Endowment for the Arts National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1982. Respectfully, F. S. M. Hodsoll Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. March 1983 Contents Chairman’s Statement 3 The Agency and Its Functions 6 The National Council on the Arts 7 Programs 8 Dance 10 Design Arts 30 Expansion Arts 46 Folk Arts 70 Inter-Arts 82 International 96 Literature 98 Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television 114 Museum 132 Music 160 Opera-Musical Theater 200 Theater 210 Visual Arts 230 Policy, Planning and Research 252 Challenge Grants 254 Endowment Fellows 259 Research 261 Special Constituencies 262 Office for Partnership 264 Artists in Education 266 State Programs 272 Financial Summary 277 History of Authorizations and Appropriations 278 The descriptions of the 5,090 grants listed in this matching grants, advocacy, and information. In 1982 Annual Report represent a rich variety of terms of public funding, we are complemented at artistic creativity taking place throughout the the state and local levels by state and local arts country. These grants testify to the central impor agencies. tance of the arts in American life and to the TheEndowment’s1982budgetwas$143million. fundamental fact that the arts ate alive and, in State appropriations from 50 states and six special many cases, flourishing, jurisdictions aggregated $120 million--an 8.9 per The diversity of artistic activity in America is cent gain over state appropriations for FY 81. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

Class of 1964 Th 50 Reunion

Class of 1964 th 50 Reunion BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY 50th Reunion Special Thanks On behalf of the Offi ce of Development and Alumni Relations, we would like to thank the members of the Class of 1964 Reunion Committee Joel M. Abrams, Co-chair Ellen Lasher Kaplan, Co-chair Danny Lehrman, Co-chair Eve Eisenmann Brooks, Yearbook Coordinator Charlotte Glazer Baer Peter A. Berkowsky Joan Paller Bines Barbara Hayes Buell Je rey W. Cohen Howard G. Foster Michael D. Freed Frederic A. Gordon Renana Robkin Kadden Arnold B. Kanter Alan E. Katz Michael R. Lefkow Linda Goldman Lerner Marya Randall Levenson Michael Stephen Lewis Michael A. Oberman Stuart A. Paris David M. Phillips Arnold L. Reisman Leslie J. Rivkind Joe Weber Jacqueline Keller Winokur Shelly Wolf Class of 1964 Timeline Class of 1964 Timeline 1961 US News • John F. Kennedy inaugurated as President of the United World News States • East Germany • Peace Corps offi cially erects the Berlin established on March Wall between East 1st and West Berlin • First US astronaut, to halt fl ood of Navy Cmdr. Alan B. refugees Shepard, Jr., rockets Movies • Beginning of 116.5 miles up in 302- • The Parent Trap Checkpoint Charlie mile trip • 101 Dalmatians standoff between • “Freedom Riders” • Breakfast at Tiffany’s US and Soviet test the United States • West Side Story Books tanks Supreme Court Economy • Joseph Heller – • The World Wide decision Boynton v. • Average income per TV Shows Catch 22 Died this Year Fund for Nature Virginia by riding year: $5,315 • Wagon Train • Henry Miller - • Ty Cobb (WWF) started racially integrated • Unemployment: • Bonanza Tropic of Cancer • Carl Jung • 40 Dead Sea interstate buses into the 5.5% • Andy Griffi th • Lewis Mumford • Chico Marx Scrolls are found South. -

Liminal Losers: Breakdowns and Breakthroughs in Reality Television's Biggest Hit

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-2013 Liminal Losers: Breakdowns and Breakthroughs in Reality Television's Biggest Hit Caitlin Rickert Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, and the Health Communication Commons Recommended Citation Rickert, Caitlin, "Liminal Losers: Breakdowns and Breakthroughs in Reality Television's Biggest Hit" (2013). Master's Theses. 136. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/136 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIMINAL LOSERS: BREAKDOWNS AND BREAKTHROUGHS IN REALITY TELEVISION’S BIGGEST HIT by Caitlin Rickert A Thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts School of Communication Western Michigan University April 2013 Thesis Committee: Heather Addison, Ph. D., Chair Sandra Borden, Ph. D. Joseph Kayany, Ph. D. LIMINAL LOSERS: BREAKDOWNS AND BREAKTHROUGHS IN REALITY TELEVISION’S BIGGEST HIT Caitlin Rickert, M.A. Western Michigan University, 2013 This study explores how The Biggest Loser, a popular television reality program that features a weight-loss competition, reflects and magnifies established stereotypes about obese individuals. The show, which encourages contestants to lose weight at a rapid pace, constructs a broken/fixed dichotomy that oversimplifies the complex issues of obesity and health. My research is a semiotic analysis of the eleventh season of the program (2011), focusing on three pairs of contestants (or “couples” teams) that each represent a different level of commitment to the program’s values. -

Family Aidan Quinn

Sensory Strategies | Latest Research | Healing Through Nutrition Family Wellness FEB-MAR 2014 Healthy ISSUE 54 Mind, Body & Spirit Providing Hope and Help for Autism Families Green Home– Aidan Healthy Kids Top family health Quinn strategies from Speaks out on Deirdre Imus parenting, vaccines, and unmet needs Toxins, Allergens, in the ASD community & ASD Bestselling author Dr. Doris Rapp with what you need to know NOW The Mercury Debate Conflicting Evidence of Toxicity The Purest Nutritional Supplements in the World! E THAN 950 C OR ON M TA OR M F IN D A E N T T S S E ! T H . e . a e v r y o M M e t & a s ls e id $ ic Ba st cte Pe ria d $ $ Yeast $ Mol E THAN 950 C OR ON M TA OR M F IN D A E N T T S S E ! THAN 950 T ORE CO M NT H Every ingredient* in every product R A . M e . O . F I a N e v r D A E N y o T T S M M S E e ! & T ta s H l . e s e . a ® d i e $ v r c y B ti o a s M c e M t P e er t & ia $ a s manufactured by Kirkman is $ old ls e Yeast $ M id $ ic Ba st cte Pe ria d $ $ Yeast $ Mol tested for more than 950 environmental contaminants! * except in lotions, creams and oils www.kirkmangroup.com Use Key Code AF214 for 20% OFF [email protected] your order of $100 or more. -

Sheila Nevins Joins MTV Studios to Launch MTV Documentary Films

Sheila Nevins Joins MTV Studios to Launch MTV Documentary Films May 7, 2019 Longtime president of HBO Documentary Films to shepherd new generation of documentary filmmakers exploring issues that impact youth NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--May 7, 2019-- MTV, a unit of Viacom (NASDAQ:VIAB), today announced that Sheila Nevins — the legendary producer who redefined modern documentary storytelling and won dozens of Emmy® and Peabody® Awards as President of HBO Documentary Films — will joinMTV to launch MTV Documentary Films. As part of MTV Studios, the new division will develop documentary films and specials for third-party streaming services, premium networks and MTV platforms. Under Nevins’ leadership, MTV Documentary Films will embrace a new generation of filmmakers exploring the social, political and cultural trends and stories important to young people. This press release features multimedia. View the full release here: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20190507005987/en/ “MTV has always been at the forefront of youth culture, and the generation that is growing up now will change the world in ways we can’t even imagine,” said Nevins. “I’m excited to join MTV with electrifying stories that explore the crises and commitments that young people face every day.” “Throughout her stellar career, Sheila has elevated documentaries into one of the most compelling, culturally influentially forms of modern storytelling,” said Chris McCarthy, President of MTV. “As we grow and expand MTV, we’re excited for Sheila to bring a new generation of filmmakers to the forefront and continue to extend our creativity and cultural impact.” Nina L. Diaz, President of Entertainment for MTV, added, “What we started two decades ago with MTV News and Docs continues to inspire today.