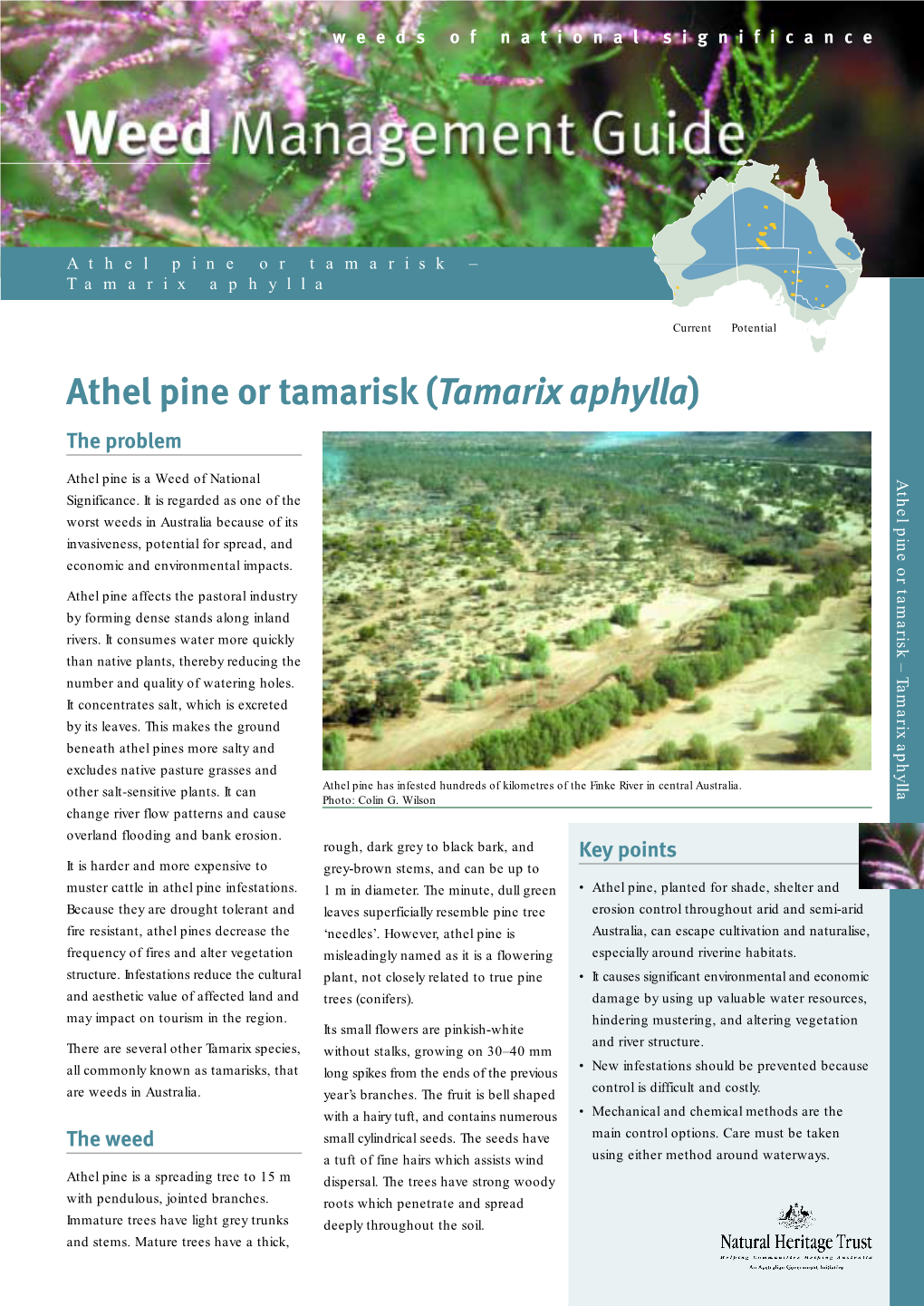

Athel Pine Or Tamarisk (Tamarix Aphylla) the Problem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overcoming the Challenges of Tamarix Management with Diorhabda Carinulata Through the Identification and Application of Semioche

OVERCOMING THE CHALLENGES OF TAMARIX MANAGEMENT WITH DIORHABDA CARINULATA THROUGH THE IDENTIFICATION AND APPLICATION OF SEMIOCHEMICALS by Alexander Michael Gaffke A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ecology and Environmental Sciences MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana May 2018 ©COPYRIGHT by Alexander Michael Gaffke 2018 All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project would not have been possible without the unconditional support of my family, Mike, Shelly, and Tony Gaffke. I must thank Dr. Roxie Sporleder for opening my world to the joy of reading. Thanks must also be shared with Dr. Allard Cossé, Dr. Robert Bartelt, Dr. Bruce Zilkowshi, Dr. Richard Petroski, Dr. C. Jack Deloach, Dr. Tom Dudley, and Dr. Dan Bean whose previous work with Tamarix and Diorhabda carinulata set the foundations for this research. I must express my sincerest gratitude to my Advisor Dr. David Weaver, and my committee: Dr. Sharlene Sing, Dr. Bob Peterson and Dr. Dan Bean for their guidance throughout this project. To Megan Hofland and Norma Irish, thanks for keeping me sane. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................1 Tamarix ............................................................................................................................1 Taxonomy ................................................................................................................1 Introduction -

Bat Conservation 2021

Bat Conservation Global evidence for the effects of interventions 2021 Edition Anna Berthinussen, Olivia C. Richardson & John D. Altringham Conservation Evidence Series Synopses 2 © 2021 William J. Sutherland This document should be cited as: Berthinussen, A., Richardson O.C. and Altringham J.D. (2021) Bat Conservation: Global Evidence for the Effects of Interventions. Conservation Evidence Series Synopses. University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. Cover image: Leucistic lesser horseshoe bat Rhinolophus hipposideros hibernating in a former water mill, Wales, UK. Credit: Thomas Kitching Digital material and resources associated with this synopsis are available at https://www.conservationevidence.com/ 3 Contents Advisory Board.................................................................................... 11 About the authors ............................................................................... 12 Acknowledgements ............................................................................. 13 1. About this book ........................................................... 14 1.1 The Conservation Evidence project ................................................................................. 14 1.2 The purpose of Conservation Evidence synopses ............................................................ 14 1.3 Who this synopsis is for ................................................................................................... 15 1.4 Background ..................................................................................................................... -

Mammals of Jordan

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Mammals of Jordan Z. AMR, M. ABU BAKER & L. RIFAI Abstract: A total of 78 species of mammals belonging to seven orders (Insectivora, Chiroptera, Carni- vora, Hyracoidea, Artiodactyla, Lagomorpha and Rodentia) have been recorded from Jordan. Bats and rodents represent the highest diversity of recorded species. Notes on systematics and ecology for the re- corded species were given. Key words: Mammals, Jordan, ecology, systematics, zoogeography, arid environment. Introduction In this account we list the surviving mammals of Jordan, including some reintro- The mammalian diversity of Jordan is duced species. remarkable considering its location at the meeting point of three different faunal ele- Table 1: Summary to the mammalian taxa occurring ments; the African, Oriental and Palaearc- in Jordan tic. This diversity is a combination of these Order No. of Families No. of Species elements in addition to the occurrence of Insectivora 2 5 few endemic forms. Jordan's location result- Chiroptera 8 24 ed in a huge faunal diversity compared to Carnivora 5 16 the surrounding countries. It shelters a huge Hyracoidea >1 1 assembly of mammals of different zoogeo- Artiodactyla 2 5 graphical affinities. Most remarkably, Jordan Lagomorpha 1 1 represents biogeographic boundaries for the Rodentia 7 26 extreme distribution limit of several African Total 26 78 (e.g. Procavia capensis and Rousettus aegypti- acus) and Palaearctic mammals (e. g. Eri- Order Insectivora naceus concolor, Sciurus anomalus, Apodemus Order Insectivora contains the most mystacinus, Lutra lutra and Meles meles). primitive placental mammals. A pointed snout and a small brain case characterises Our knowledge on the diversity and members of this order. -

Zootaxa, Lepidoptera, Noctuidae, Schinia

Zootaxa 788: 1–4 (2004) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA 788 Copyright © 2004 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A new species of Schinia Hübner from riparian habitats in the Grand Canyon (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae: Heliothinae) MICHAEL G. POGUE1 1Systematic Entomology Laboratory, PSI, Agricultural Research Service, U. S. Department of Agriculture, c/o Smithsonian Institution, P.O. Box 37012, NMNH, MRC-168, Washington, DC 20013-7012, USA [email protected] Abstract Schinia immaculata, new species, is described from riparian habitats along the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon. Habitats include the shoreline, new high water dominated by tamarisk (Tamarix sp., Tamaricaceae), and old high water characterized by mesquite (Prosopis sp., Fabaceae), acacia (Acacia sp., Fabaceae), and desert shrubs. Adult and male genitalia are illustrated and compared with Schinia biundulata Smith. Key words: systematics, genitalia, tamarisk, mesquite, acacia Introduction Dr. Neil Cobb and Robert Delph of Northern Arizona University are currently involved in an arthropod inventory and monitoring project in the Grand Canyon National Park. This project will inventory and characterize the riparian arthropod fauna associated with the different river flow stage riparian environments along the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon. During examination of this material a new species of Schinia Hübner, 1818, was discovered. Schinia is the most diverse genus in the subfamily Heliothinae with 118 spe- cies (Hardwick 1996, Knudson et al. 2003, Pogue and Harp 2003a, Pogue and Harp 2003b, Pogue and Harp 2003c, Pogue and Harp 2004). This new species is unusual because of its lack of forewing pattern and solid color hindwing. -

Poplar Chap 1.Indd

Populus: A Premier Pioneer System for Plant Genomics 1 1 Populus: A Premier Pioneer System for Plant Genomics Stephen P. DiFazio,1,a,* Gancho T. Slavov 1,b and Chandrashekhar P. Joshi 2 ABSTRACT The genus Populus has emerged as one of the premier systems for studying multiple aspects of tree biology, combining diverse ecological characteristics, a suite of hybridization complexes in natural systems, an extensive toolbox of genetic and genomic tools, and biological characteristics that facilitate experimental manipulation. Here we review some of the salient biological characteristics that have made this genus such a popular object of study. We begin with the taxonomic status of Populus, which is now a subject of ongoing debate, though it is becoming increasingly clear that molecular phylogenies are accumulating. We also cover some of the life history traits that characterize the genus, including the pioneer habit, long-distance pollen and seed dispersal, and extensive vegetative propagation. In keeping with the focus of this book, we highlight the genetic diversity of the genus, including patterns of differentiation among populations, inbreeding, nucleotide diversity, and linkage disequilibrium for species from the major commercially- important sections of the genus. We conclude with an overview of the extent and rapid spread of global Populus culture, which is a testimony to the growing economic importance of this fascinating genus. Keywords: Populus, SNP, population structure, linkage disequilibrium, taxonomy, hybridization 1Department of Biology, West Virginia University, Morgantown, West Virginia 26506-6057, USA; ae-mail: [email protected] be-mail: [email protected] 2 School of Forest Resources and Environmental Science, Michigan Technological University, 1400 Townsend Drive, Houghton, MI 49931, USA; e-mail: [email protected] *Corresponding author 2 Genetics, Genomics and Breeding of Poplar 1.1 Introduction The genus Populus is full of contrasts and surprises, which combine to make it one of the most interesting and widely-studied model organisms. -

Tamarix Gallica (French Tamarisk) French Tamarisk Is a Small Tree Known to Be Highly Invasive

Tamarix gallica (French tamarisk) French tamarisk is a small tree known to be highly invasive. It does very well in desert areas, and compete other plants to become the dominant plant type if the right conditions are found. Tamarisk grows in well drained soil of any type, and needs full sun. This plant is very attractive. It has beautyful pink flowers that are very catchy, especially for insects and butterflies, and a feathery green folliage. Landscape Information French Name: Tamaris des Canaries Pronounciation: TAM-uh-riks GAL-ee-kuh Plant Type: Tree Origin: Southern Europe Heat Zones: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 Hardiness Zones: 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Uses: Specimen, Wildlife, Erosion control, Cut Flowers / Arrangements Size/Shape Growth Rate: Fast Tree Shape: Spreading Canopy Texture: Fine Plant Image Height at Maturity: 3 to 5 m Spread at Maturity: 3 to 5 meters Tamarix gallica (French tamarisk) Botanical Description Foliage Leaf Arrangement: Alternate Leaf Venation: Nearly Invisible Leaf Persistance: Deciduous Leaf Type: Simple Leaf Blade: Less than 5 Leaf Shape: Linear Leaf Margins: Entire Leaf Textures: Coarse Leaf Scent: No Fragance Color(growing season): Green Color(changing season): Green Flower Flower Image Flower Showiness: True Flower Size Range: 3 - 7 Flower Sexuality: Diecious (Monosexual) Flower Scent: No Fragance Flower Color: Purple, Pink Seasons: Spring, Summer Trunk Trunk Susceptibility to Breakage: Generally resists breakage Number of Trunks: Single Trunk Trunk Esthetic Values: Showy, -

Miscellaneous Invasive Shrubs and Grasses

Ramsey County Cooperative Weed Management Area not-WANTEd INVASIVE SHRUBS & GRASSES IN YOUR LANDSCAPE! EARLY DETECTION & CONTROL WILL PREVENT INFESTATIONS Amur Maple Winged Burning Bush Japanese Barberry MA W Ribbon Ribbon grass Ted leaves: Beverly Silver grass photos: Ramsey County C Tamarisk / Salt Cedar Ribbon / Variegated Reed Canary Grass Chinese / Amur Silver Grass For more information visit the RCCWMA Website: www.co.ramsey.mn.us/cd/cwma.htm or visit us on Facebook Photos courtesy minnesotawildflowers.info, except as noted MORE INFO Ramsey County Cooperative Weed Management Area Not-WANTEd INVASIVE SHRUBS & GRASSES IN YOUR LANDSCAPE! These shrubs and grasses may spread from your yard to natural areas; displacing native plants and disrupting woodland, grassland or aquatic ecosystems. AMUR MAPLE (Acer ginnala) was imported from TAMARISK or SALT CEDAR (Tamarix ssp.) is northern Asia in the late 1800s for its bright red, a shrub or small tree with scaly, cedar-like orange and yellow fall color. Found in roadside leaves, which contain volatile oils. Flowers are plantings, hedges and wind-breaks; may grow 20 long, thin, pink or white spikes; blooms June - feet high and 30 feet wide, with smooth gray September. This species affects water levels and bark. Opposite, narrow leaves are three-lobed; increases riparian wildfires in the western U.S. the middle lobe longest; reaching 3 to 5 inches. One mature plant may remove 60 + gallons of Small clusters of yellowish to white flowers groundwater each day with its deep taproot. bloom April - May. A vast number seeds are Special leaf glands accumulate salt. As leaves held in narrow-angled samara pairs, each 1 - 1.5 drop over time, soil salinity increases, preventing inch long. -

Georgia Native Trees Considered Invasive in Other Parts of the Country. Scientific Name Common Name Scientific Name Common Name

Invasive Trees of Georgia Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care, Warnell School, UGA Georgia has many species of trees. Some are native trees and some have been introduced from outside the state, nation, or continent. Most of Georgia’s trees are well-behaved and easily develop into sustainable shade and street trees. A few tree species have an extrodinary ability to upsurp resources and take over sites from other plants. These trees are called invasive because they effectively invade sites, many times eliminating other species of plants. There are a few tree species native to Georgia which are considered invasive in other parts of the country. These native invasives, may be well-behaved in Georgia, but reproduce and take over sites elsewhere, and so have gained an invasive status from at least one other invasive species list. Table 1. There are hundreds of trees which have been introduced to Georgia landscapes. Some of these exotic / naturalized trees are considered invasive. The selected list of Georgia invasive trees listed here are notorious for growing rampantly and being diffi- cult to eradicate. Table 2. They should not be planted. Table 1: Georgia native trees considered invasive in other parts of the country. scientific name common name scientific name common name Acacia farnesiana sweet acacia Myrica cerifera Southern bayberry Acer negundo boxelder Pinus taeda loblolly pine Acer rubrum red maple Populus deltoides Eastern Fraxinus americana white ash cottonwood Fraxinus pennsylvanica green ash Prunus serotina black cherry Gleditsia triacanthos honeylocust Robinia pseudoacacia black locust Juniperus virginiana eastern Toxicodendron vernix poison sumac redcedar Table 2: Introduced (exotic) tree / shrub species found in Georgia listed at a regional / national level as being ecologically invasive. -

Tamarix Chinensis Lour.: Saltcedar Or Five-Stamen Tamarisk

T&U genera Layout 1/31/08 12:50 PM Page 1087 Tamaricaceae—Tamarix family T Tamarix chinensis Lour. saltcedar or five-stamen tamarisk Wayne D. Shepperd Dr. Shepperd is a research silviculturist at the USDA Forest Service’s Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fort Collins, Colorado Synonym. T. pentrandra Pall. Flowering and fruiting. The pink to white flowers, Growth habit, occurrence, and use. Saltcedar borne in terminal panicles, bloom from March through (Tamarix chinensis (Lour.)) and smallflower tamarisk (T. September. A succession of small capsular fruits ripen and parviflora DC.) hybridize in the Southwest (Baum 1967; split open during the period from late April through October Horton and Campbell 1974) and are deciduous, pentamerous in Arizona (Horton and others 1960). Seeds are minute and tamarisks that are both commonly referred to as saltcedar. have an apical tuft of hairs (figures 1 and 2) that facilitates Saltcedar is a native of Eurasia that has naturalized in the dissemination by wind. Large numbers of small short-lived southwestern United States within the last century. It was seeds are produced that can germinate while floating on introduced into the eastern United States in the 1820s water, or within 24 hours after wetting (Everitt 1980). (Horton 1964) and was once widely cultivated as an orna- Collection, extraction, and storage. Fruits can be mental, chiefly because of its showy flowers and fine, grace- collected by hand in the spring, summer, or early fall. It is ful foliage. However, saltcedar has been an aggressive invad- not practical to extract the seeds from the small fruits. At er of riparian ecosystems in the Southwest (Reynolds and least half of the seeds in a lot still retained their viability Alexander 1974) and is the subject of aggressive eradication after 95 weeks in storage at 4.4 °C, but seeds stored at room campaigns. -

Trees of Somalia

Trees of Somalia A Field Guide for Development Workers Desmond Mahony Oxfam Research Paper 3 Oxfam (UK and Ireland) © Oxfam (UK and Ireland) 1990 First published 1990 Revised 1991 Reprinted 1994 A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library ISBN 0 85598 109 1 Published by Oxfam (UK and Ireland), 274 Banbury Road, Oxford 0X2 7DZ, UK, in conjunction with the Henry Doubleday Research Association, Ryton-on-Dunsmore, Coventry CV8 3LG, UK Typeset by DTP Solutions, Bullingdon Road, Oxford Printed on environment-friendly paper by Oxfam Print Unit This book converted to digital file in 2010 Contents Acknowledgements IV Introduction Chapter 1. Names, Climatic zones and uses 3 Chapter 2. Tree descriptions 11 Chapter 3. References 189 Chapter 4. Appendix 191 Tables Table 1. Botanical tree names 3 Table 2. Somali tree names 4 Table 3. Somali tree names with regional v< 5 Table 4. Climatic zones 7 Table 5. Trees in order of drought tolerance 8 Table 6. Tree uses 9 Figures Figure 1. Climatic zones (based on altitude a Figure 2. Somali road and settlement map Vll IV Acknowledgements The author would like to acknowledge the assistance provided by the following organisations and individuals: Oxfam UK for funding me to compile these notes; the Henry Doubleday Research Association (UK) for funding the publication costs; the UK ODA forestry personnel for their encouragement and advice; Peter Kuchar and Richard Holt of NRA CRDP of Somalia for encouragement and essential information; Dr Wickens and staff of SEPESAL at Kew Gardens for information, advice and assistance; staff at Kew Herbarium, especially Gwilym Lewis, for practical advice on drawing, and Jan Gillet for his knowledge of Kew*s Botanical Collections and Somalian flora. -

(Tamarix Aphylla) and Athel Hybrid (Tamarix Aphylla X Tamarix Ramosissima) Establishment and Control at Lake Mead National Recreation Area

Athel (Tamarix aphylla) and Athel hybrid (Tamarix aphylla X Tamarix ramosissima) Establishment and Control at Lake Mead National Recreation Area. Carrie Norman, Curt Deuser, and Josh Hoines Lake Mead National Recreation Area, 601 Nevada Highway, Boulder City, Nevada 89005 Athel is a large evergreen ornamental tree that has been planted throughout the Southwest since the 1950’s. Athel was considered benign because it was thought to produce non-viable seed unlike its invasive relative, tamarisk. However, athel began establishing in the wild from seed on Lake Mead in 1983. Lake Mead NRA has been actively controlling athel since November 2004 along the high water mark of Lake Mead shoreline (439 miles) to prevent it from spreading throughout the Colorado River Drainage. The NPS contracts Nevada Conservation Corp crews and the Lake Mead Exotic Plant Management Team to implement the control efforts of athel and the hybrid. Since 2004 Lake Mead NRA has controlled 72,156 athel and 11,749 hybrids. Control methods have Athel growing along Lake Mead shoreline when water Athel growing along high water level of shoreline been effective and follow up monitoring and retreatment is planned during level was at full pool even after the water level has dropped 100+ feet the 2009 field season. Based on observations at Lake Mead NRA, the invasive potential of athel is high, particularly in light of its hybridization Spraying cambium layer with herbicide potential with tamarisk thus creating a new noxious weed. Natural Cutting into cambium layer and recording location with a gps resource land managers should be vigilant in monitoring current athel populations to ensure they do not become invasive or hybridize with tamarisk. -

Tamarix Aphylla Global Invasive Species Database (GISD)

FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Tamarix aphylla Tamarix aphylla System: Terrestrial Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Plantae Magnoliophyta Magnoliopsida Violales Tamaricaceae Common name Tamariske (German), woestyntamarisk (Afrikaans), athel-pine (English), saltcedar (English), tamarix (English), tamarisk (English), desert tamarix (English), taray (Spanish), Athel tamarisk (English), tamaris (French), athel-tree (English), farash (English, India) Synonym Tamarix articulata , Vahl Thuja aphylla , L. Similar species Summary The athel pine, Tamarix aphylla (L.) Karst., is native to Africa and tropical and temperate Asia. It is an evergreen tree that grows to 15 m, and has been introduced around the world, mainly as shelter and for erosion control. Seedlings of T. aphylla develop readily once established, and grow woody root systems that can reach as deep as 50 m into soil and rock. It can extract salts from soil and water excrete them through their branches and leaves. T. aphylla can have the following effects on ecological systems: dry up viable water sources; increase surface soil salinity; modification of hydrology; decrease native biodiversity of plants, invertebrates, birds, fish and reptiles; and increase fire risk. Management techniques that have been used to control T. aphylla include mechanical clearing - using both machinery and by hand - and/or herbicides. view this species on IUCN Red List Notes Tamarix aphylla Is thought to hybridise with the smallflower tamarisk, T. parviflora. (National Athel Pine Management Committee 2008). Global Invasive Species Database (GISD) 2021. Species profile Tamarix aphylla. Pag. 1 Available from: http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/species.php?sc=697 [Accessed 28 September 2021] FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Tamarix aphylla Management Info Management techniques that have been used to control Tamarix sp.