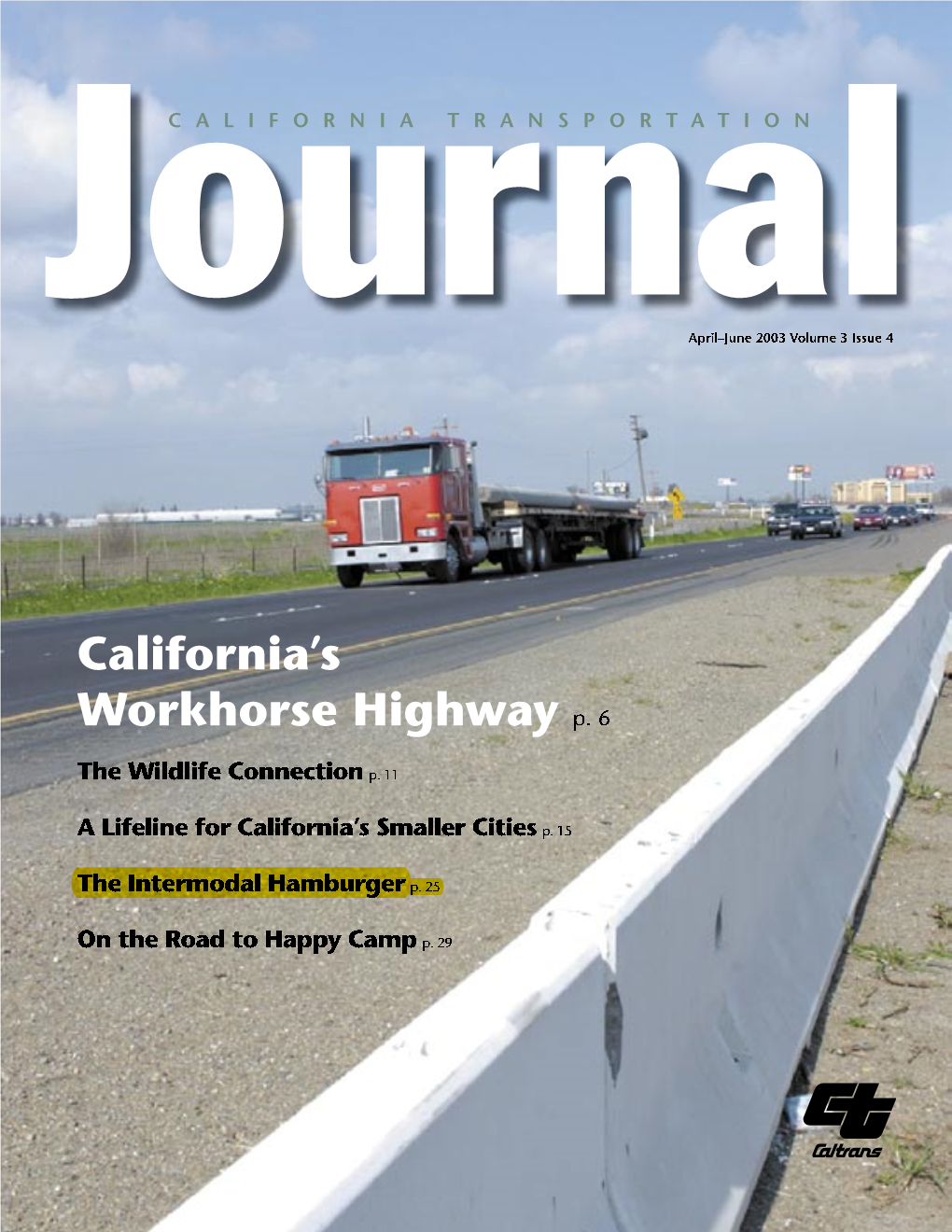

California's Workhorse Highway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State of CA, Miscellaneous/Home Rule (34)

State of CA, Miscellaneous/Home Rule (34) Mtg Date Subject Vol. Page Minutes 3/15/90 Joint meeting with City of Grass Valley. 49 972 4/10/90 Joint meeting with City of Nevada City. 49 1073 8/7/90 Joint meeting with City of Grass Valley. 50 132 1/27/92 Joint meeting with County of Placer. 51 717A 3/3/92 Res. 92-132 pertaining to the use of Courtroom and Baord Chamber Space 51 833 for all County Central Committees 3/23/92 Joint meeting with Placer County. 51 905 7/7/92 A Letter from Sierra-Sacramento Valley Emergency Medical Services 51 1252 Agency Requesting Opposition to the State Budget Task Force's Recommendation to Eliminate State Emergency Medical Services Authority's Budget. 7/7/92 A Letter from John Zivnuska Requesting Support for Naming a Small 51 1253 Granite Peak in Nevada County "Mount Marliave" in Commemoration of Chester Marliave (1885-1991) and His Two Sons. The Peak Lies About 2 Miles Northwest of Soda Springs. A Request to Support Proposition 155, the $1 Billion Bond Act for Rail 51 1273 Transportation. Discussion of Potential Impacts to Services from the Upcoming Jerry Garcia 51 1273 "Grateful Dead" Concert August 29 in Squaw Valley, Placer County. Request for a Letter of Support from the Board of Supervisors to the Nevada 51 1274 County Arts Council for a $75,000 Grant from the National Endowment of the Arts. Request by Ms. Beckwith for County funding for Sierra Services for the 51 1299 Blind be withheld pending investigation of that organization, including an appropriate needs assessment performed by an impartial agency. -

HIGH-SPEED RAIL 2 Silicon Valley Business Journal August 5, 2016 3

TABLE of EXPERTS A digital supplement to the Silicon Valley Business Journal | August 5, 2016 HIGH-SPEED RAIL 2 SILICON VALLEY BUSINess JOURNAL AUGUST 5, 2016 3 “The exciting thing Silicon Valley’s experts talk about is we’re not talking California’s plan for high-speed rail Introductory Remarks about if, but how hen California voters in 2008 approved Proposition 1A – nearly $10 billion in bonds to From 1995 to 2014, Rod Diridon Sr. was executive director of W construct the first phase of a high-speed rail the Mineta Transportation Institute, a transportation policy to build this.” system for California and improve the rail services that research center created in 1991 by Congress. He is known JEFF MOrales, would connect to it – it was obvious that it would take years as the “father” of modern transit service in Silicon Valley California High-Speed Rail Authority before anyone would ride one of the 200-mph trains from and frequently provides legislative testimony on sustainable the Bay Area to Los Angeles. transportation issues. The region’s main train station was Even after the California High-Speed Rail Authority renamed the “San Jose Diridon Station” upon his retirement announced last February that San Jose would be the Rod Diridon Sr. from public office. Diridon received a B.S. in accounting and northern terminus for the first operating segment, the 2025 Executive Director Emeritus, Mineta MSBA in statistics in 1963 from San Jose State University. service starting date still seemed like the distant future. Transportation Institute But the work to make that opening date a reality is under View Rod Diridon’s full presentation online way now. -

California--State of Change Program

California State of Change December 3, 2014 Sheraton Grand Hotel Sacramento, CA #PPICfuture Agenda 8:30 a.m. Registration and continental breakfast 9:00 a.m. Welcome Donna Lucas, Lucas Public Affairs 9:15 a.m. Sutton Family Speaker Series Keynote Moderator: Mark Baldassare, PPIC Nancy McFadden, Office of the Governor 10:00 a.m. Break 10:15 a.m. Session 1: California’s New Leadership Presider: Hans Johnson, PPIC Moderator: Gregory Rodriguez, Zócalo Public Square Assemblymember Rocky Chávez, State of California Assemblymember Lorena Gonzalez, State of California Assemblymember Chris Holden, State of California 11:30 a.m. Break 11:45 a.m. Session 2 (lunch): Government 2.0 Presider: Patrick Murphy, PPIC Moderator: John Myers, KQED News Controller John Chiang, State of California Mayor Ashley Swearengin, City of Fresno Antonio Villaraigosa, USC Price School of Public Policy 1:15 p.m. Break California—State of Change #PPICfuture 1:30 p.m. Session 3: Economic Shifts Presider: Sarah Bohn, PPIC Moderator: John Diaz, San Francisco Chronicle Antonia Hernández, California Community Foundation Supervisor Joe Simitian, Santa Clara County Board of Supervisors Allan Zaremberg, California Chamber of Commerce 2:45 p.m. Break 3:00 p.m. Session 4: Cutting Edges Presider: Ellen Hanak, PPIC Moderator: Patt Morrison, Los Angeles Times and Southern California Public Radio Jeff Morales, California High-Speed Rail Authority Mary Nichols, California Air Resources Board Art Torres, California Institute for Regenerative Medicine 4:15 p.m. Closing remarks and adjourn 4:30 p.m.– Reception 5:30 p.m. California—State of Change #PPICfuture Participants Mark Baldassare is president and CEO of the Public Policy Institute of California, where he also holds the Arjay and Frances Fearing Miller Chair in Public Policy and directs the PPIC Statewide Survey―a large-scale public opinion project designed to develop an in-depth profile of the social, economic, and political forces at work in California elections and in shaping the state’s public policies. -

The Us Transit Bus Manufacturing Industry

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Mineta Transportation Institute Publications 10-2016 The SU Transit Bus Manufacturing Industry David Czerwinski San Jose State University, [email protected] Xu (Cissy) Hartling Salem State University Jing Zhang San Jose State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/mti_publications Part of the Public Policy Commons, and the Transportation Commons Recommended Citation David Czerwinski, Xu (Cissy) Hartling, and Jing Zhang. "The SU Transit Bus Manufacturing Industry" Mineta Transportation Institute Publications (2016). This Report is brought to you for free and open access by SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mineta Transportation Institute Publications by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MTI Funded by U.S. Department of Services Transit Census California of Water 2012 Transportation and California The US Transit Bus Department of Transportation Manufacturing Industry MTI ReportMTI 12-02 December 2012 MTI Report 12-66 MINETA TRANSPORTATION INSTITUTE MTI FOUNDER LEAD UNIVERSITY OF MNTRC Hon. Norman Y. Mineta The Mineta Transportation Institute (MTI) was established by Congress in 1991 as part of the Intermodal Surface Transportation MTI/MNTRC BOARD OF TRUSTEES Equity Act (ISTEA) and was reauthorized under the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st century (TEA-21). MTI then successfully competed to be named a Tier 1 Center in 2002 and 2006 in the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Founder, Honorable Norman Joseph Boardman (Ex-Officio) Diane Woodend Jones (TE 2019) Richard A. White (Ex-Officio) Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU). -

Download the Summer 2016 Issue (PDF)

ROCK ’N’ ROLL PHOTOGRAPHER FASTING FOR LOVE MICRO VISTAS THE GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE SUMMER 2016 THE UPs AND DOWNs OF A CAMPAIGN AND THE campaign director ARMY OF ALUMNI SUPPORTERS policy manager social director media team ALONG FOR THE communications RIDE advance field organizer Tim Miller, BA ’04 team (Page 45) coordinator press secretary Alex Hornbrook, BA ’07 (Page 48) candidate Peter Frampton tosses his guitar pick into the crowd at the Oakland Coliseum in a July 1977 moment captured by photographer Michael Zagaris, BA ’67. In October, the iconic chronicler of rock and sports is releasing the first of three coffee-table books spanning his nearly five decades behind the lens. gw magazine / Summer 2016 GW MAGAZINE SUMMER 2016 A MAGAZINE FOR ALUMNI AND FRIENDS CONTENTS [Features] 28 / The Fight and the Fury of the Z-Man Iconic photographer and eternal San Franciscan Michael Zagaris, BA ’67, has shot rock gods and all-stars, stood up to The Man and almost died twice. He’s spent his life doing everything you always wanted to do, and now that he’s getting older ... absolutely nothing’s changed. / By Matthew Stoss / 42 / Armies on the March By car and bus and plane, propped up by road food and coffee—and, in some places, good ol’ milk—quadrennial swarms of campaign staffers have been boomeranging across the nation to boost their presidential candidates. They are the people behind the people, the unseen army. / By Emily Cahn, BA ’11 / 50 / ‘Google Maps’ of the Minuscule A new imaging facility brings the nanometer and atomic worlds into focus. -

Promoting Transit-Oriented Developments by Addressing Barriers Related to Land Use, Zoning, and Value Capture

Project 1819 October 2020 Promoting Transit-Oriented Developments by Addressing Barriers Related to Land Use, Zoning, and Value Capture Shishir Mathur, PhD Aaron Gatdula, MCP M I N ET A TRAN SP ORT A TION I N STITUTE transweb.sjsu.edu MINETA TRANSPORTATION INSTITUTE MTI FOUNDER LEAD UNIVERSITY OF Mineta Consortium for Transportation Mobility Hon. Norman Y. Mineta MTI BOARD OF TRUSTEES Founded in 1991, the Mineta Transportation Institute (MTI), an organized research and training unit in partnership with the Lucas College and Graduate School of Business at San José State University (SJSU), increases mobility for all by improving the safety, Founder, Honorable Grace Crunican** Diane Woodend Jones Takayoshi Oshima efficiency,accessibility,and convenience of our nation’s transportation system.Through research,education,workforce development, Norman Mineta* Owner Principal & Chair of Board Chairman & CEO Secretary (ret.), Crunican LLC Lea + Elliott, Inc. Allied Telesis, Inc. and technology transfer, we help create a connected world. MTI leads the four-university Mineta Consortium for Transportation US Department of Transportation Mobility, a Tier 1 University Transportation Center funded by the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Office of the Assistant Donna DeMartino David S. Kim* Paul Skoutelas* Chair, Managing Director Secretary President & CEO Secretary for Research and Technology (OST-R), the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), and by private grants Abbas Mohaddes Los Angeles-San Diego-San Luis California State Transportation -

High-Speed Rail

Connecting and Transforming California DRAFT 2016 BUSINESS PLAN FEBRUARY 18, 2016 www.hsr.ca.gov 2 California High-Speed Rail Authority • www.hsr.ca.gov The California High-Speed Rail Authority (Authority) is re- Board of Directors sponsible for planning, designing, building and operating the first high-speed rail in the nation. California high- Dan Richard Chair speed rail will connect the mega-regions of the state, con- Thomas Richards tribute to economic development and a cleaner environ- Vice Chair ment, create jobs and preserve agricultural and protected Lou Correa lands. When it is completed, it will run from San Francisco Daniel Curtin to the Los Angeles basin in under three hours at speeds Bonnie Lowenthal capable of exceeding 200 miles per hour. The system will Lorraine Paskett eventually extend to Sacramento and San Diego, total- Michael Rossi ing 800 miles with up to 24 stations. In addition, we are Lynn Schenk working with regional partners to implement a statewide rail modernization plan that will invest billions of dollars in Jeff Morales local and regional rail lines to meet the state’s 21st century Chief Executive Officer transportation needs California High-Speed Rail Authority 770 L Street, Suite 620 Sacramento, CA 95814 (916) 324-1541 [email protected] www.hsr.ca.gov DRAFT 2016 Business Plan: Connecting and Transforming California 3 History of High-Speed Rail in California alifornia has evaluated the potential for high-speed rail for several decades. It first pursued the idea of a Southern California high- speed rail corridor working with Japanese partners in 1981. -

Altamont Pass Commuter Study: a Longitudinal Analysis of Perceptions and Behavior Change

Project 1917 | September 2020 Altamont Pass Commuter Study: A Longitudinal Analysis of Perceptions and Behavior Change Orestis Panagopoulos, PhD Gökçe Soydemir, PhD Xun Xu, PhD CSU TR ANSPOR TATION CONSOR TIUM transweb.sjsu.edu/csutc Mineta Transportation Institute Founded in 1991, the Mineta Transportation Institute (MTI), an organized research and training unit in partnership with the Lucas College and Graduate School of Business at San José State University (SJSU), increases mobility for all by improving the safety, efficiency, accessibility, and convenience of our nation’s transportation system. Through research, education, workforce development, and technology transfer, we help create a connected world. MTI leads the Mineta Consortium for Transportation Mobility (MCTM) funded by the U.S. Department of Transportation and the California State University Transportation Consortium (CSUTC) funded by the State of California through Senate Bill 1. MTI focuses on three primary responsibilities: Research Science in Transportation Management, plus graduate certificates that include High-Speed and Intercity Rail MTI conducts multi-disciplinary research focused on Management and Transportation Security surface transportation that contributes to effective Management. These flexible programs offer live online decision making. Research areas include: active classes so that working transportation professionals can transportation; planning and policy; security and pursue an advanced degree regardless of their location. counterterrorism; sustainable transportation and land use; transit and passenger rail; transportation engineering; transportation finance; transportation technology; and workforce and labor. MTI research Information and Technology Transfer publications undergo expert peer review to ensure the quality of the research. MTI utilizes a diverse array of dissemination methods and media to ensure research results reach those responsible for managing change. -

Railway Vision for North America L Challenges for the Future CONTENTS

RAILWAY VISION FOR NORTH AMERICA l CHALLENGES FOR THE FUTURE CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 UIC MEMBERS IN NORTH AMERICA 4 UIC ACTIONS IN NORTH AMERICA 6 OVERVIEW OF THE REGION – KEY FIGURES 8 POLITICAL AND ECOMOMIC CONTEXT 9 FOCUSSES ON MAIN ACHIEVEMENTS AND DEVELOPMENTS 16 A FEW CONCLUDING WORDS 30 RAILWAY VISION FOR NORTH AMERICA l CHALLENGES FOR THE FUTURE INTRODUCTION UIC is an international association, bringing together 230 railway companies across 95 countries on the five continents with over 30 external partners, ena- bling it to play a leading role in serving the world’s railway community. UIC is plat- form for technical study, innovation, standardisation and training with the chief aim of promoting the fundamental values of rail and the role it has played on a social, economic and societal level in modern societies over the last 92 years. In serving its members, UIC also defines the development strategy for its members within the five regions. It is in this context that recent consolida- tion work undertaken with all our members has led to the publication of seven strategic visions: Vision 2050 for Europe completed with the Rail Technical Strategy for Europe, a vision for Asia-Oceania, for the Middle-East, Africa, South America and last but not least for North America. North America, as is well known, has a long railway history and is a developing economy with advanced infrastructure enabling it to meet the strong need for mobility of goods and people. North America is also facing strong urbanisa- tion needing new intra-city and inter-city transport plans. -

Aligning Transportation Spending with Californiaâ•Žs

UC Berkeley Center for Law, Energy & the Environment Title Moving Dollars: Aligning Transportation Spending With California’s Environmental Goals Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0kx7z6p2 Author Elkind, Ethan Publication Date 2015-02-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California MOVING DOLLARS Aligning Transportation Spending With California’s Environmental Goals February 2015 Bank of America Berkeleylaw T H E EMMETT I NSTITUTE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA ON CLIMATE CHANGE AND THE ENVIRONMENT Center for Law. Energy & UCLA SCHOOL OF LAW ~ the Environment Berkeley Law \ UCLA Law About this Report This policy paper is the fifteenth in a series of reports on how climate change will create opportunities for specific sectors of the business community and how policy-makers can facilitate those opportunities. Each paper results from one-day workshop convenings that include representatives from key business, academic, and policy sectors of the targeted industries. The convenings and resulting policy papers are sponsored by Bank of America and produced by a partnership of the UCLA School of Law’s Emmett Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and UC Berkeley School of Law’s Center for Law, Energy & the Environment. Authorship The author of this policy paper is Ethan N. Elkind, Associate Director of the Climate Change and Business Research Initiative at the UCLA School of Law’s Emmett Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and UC Berkeley School of Law’s Center for Law, Energy & the Environment (CLEE). Additional contribu- tions to the report were made by Sean Hecht and Cara Horowitz of the UCLA School of Law and Jordan Diamond of the UC Berkeley School of Law. -

MOVING DOLLARS Aligning Transportation Spending with California’S Environmental Goals February 2015

MOVING DOLLARS Aligning Transportation Spending With California’s Environmental Goals February 2015 Berkeley Law \ UCLA Law About this Report This policy paper is the fifteenth in a series of reports on how climate change will create opportunities for specific sectors of the business community and how policy-makers can facilitate those opportunities. Each paper results from one-day workshop convenings that include representatives from key business, academic, and policy sectors of the targeted industries. The convenings and resulting policy papers are sponsored by Bank of America and produced by a partnership of the UCLA School of Law’s Emmett Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and UC Berkeley School of Law’s Center for Law, Energy & the Environment. Authorship The author of this policy paper is Ethan N. Elkind, Associate Director of the Climate Change and Business Research Initiative at the UCLA School of Law’s Emmett Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and UC Berkeley School of Law’s Center for Law, Energy & the Environment (CLEE). Additional contribu- tions to the report were made by Sean Hecht and Cara Horowitz of the UCLA School of Law and Jordan Diamond of the UC Berkeley School of Law. This report and its recommendations are solely a product of the UCLA and UC Berkeley Schools of Law and do not necessarily reflect the views of all individual convening participants, reviewers, or Bank of America. Acknowledgments The author and organizers are grateful to Bank of America for its generous sponsorship of the Climate Change and Business Research Initiative. We would specifically like to thank Catherine P. -

2015 APTA Awards Program

Celebrating Excellence in the Public Transportation Industry 2015 APTA AWARDS October 6, 2015 San Francisco, California 2015 American Public Transportation Association Awards Welcome to the 2015 APTA Awards! Today we come together to recognize and applaud this year’s winning individuals and organizations for their significant achievements in our industry. We are also here today to thank them for their hard work and dedication in advancing public trans- portation in North America. I encourage everyone to learn more about the winners’ accomplishments and to make the time to personally congratulate them. Winning a prestigious APTA Award is a very high honor that acknowledges you are “the best of the best.” As the 2015 stars of the public transit industry, the APTA Awards recipients are stellar leaders and innovators as well as models of excellence. Finally, as the chair of the 2015 APTA Awards Committee, I want to thank all the members of the Awards Committee for their commitment to making the awards program a success. It’s been a pleasure to serve with you. Grace Crunican Chair, 2015 APTA Awards Committee and General Manager San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District Oakland, CA Many thanks to GENFARE for sponsoring the 2015 APTA Awards Book. 2015 APTA Award Winners ORGANIZATION AWARDS OUTSTANDING PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM ACHIEVEMENT AWARD Connect Transit .......................................................................2 Metropolitan Transit Authority of Harris County (METRO) .......................................4 INDIVIDUAL AWARDS STATE DISTINGUISHED SERVICE AWARD Jeff Morales .........................................................................6 OUTSTANDING PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION BOARD MEMBER AWARD John S. Spychalski .....................................................................8 OUTSTANDING PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION BUSINESS MEMBER AWARD Angela Iannuzziello ..................................................................10 OUTSTANDING PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION MANAGER AWARD Keith T.