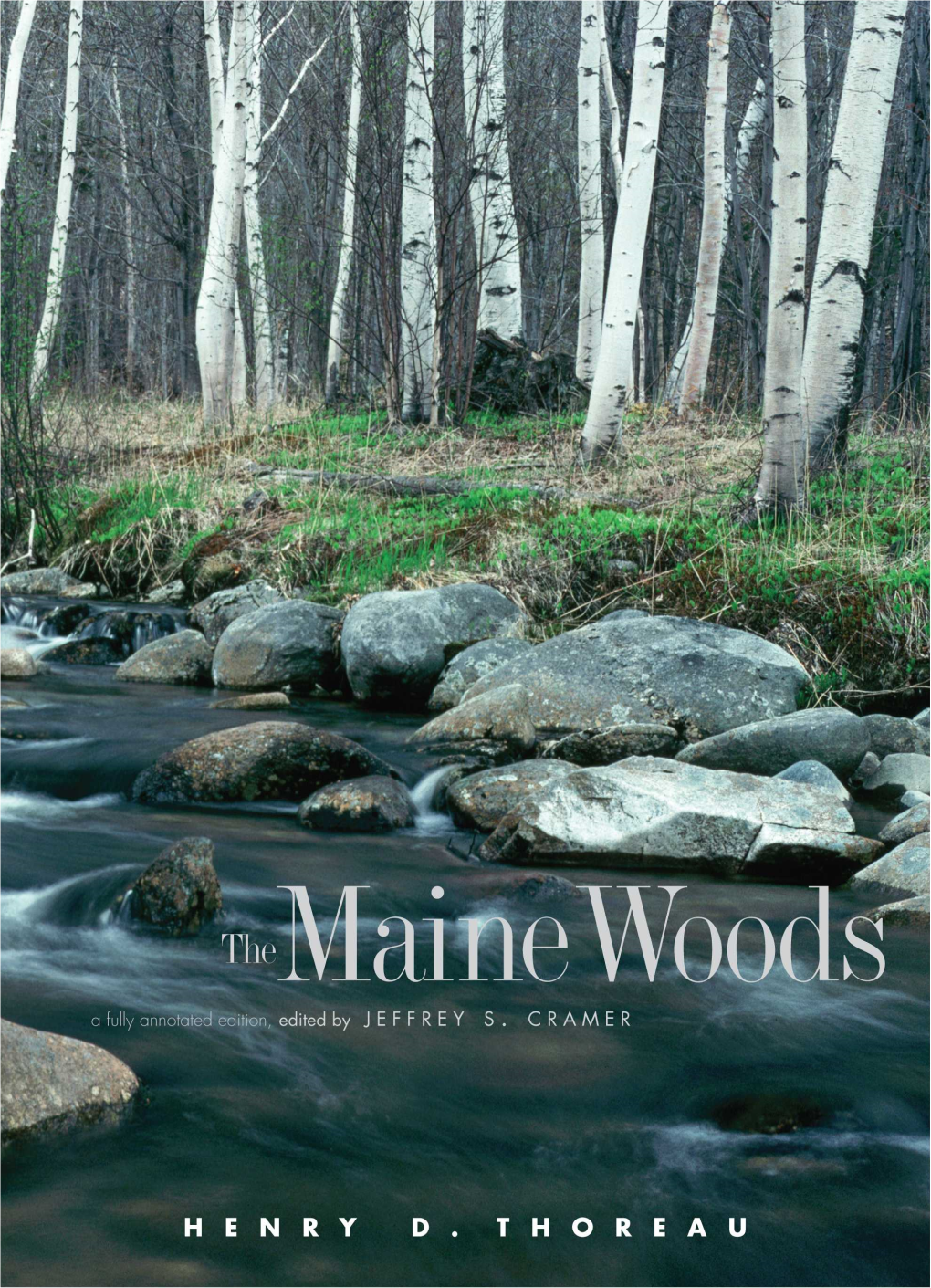

The Maine Woods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Travels in America Performed in 1806, for the Purpose of Exploring

Library of Congress Travels in America performed in 1806, for the purpose of exploring the rivers Alleghany, Monongahela, Ohio, and Mississippi, and ascertaining the produce and condition of their banks and vicinity. By Thomas Ashe, esq. ... TRAVELS IN AMERICA, PERFORMED IN 1806, For the Purpose of exploring the RIVERS ALLEGHANY, MONONGAHELA, OHIO, AND MISSISSIPPI, AND ASCERTAINING THE PRODUCE AND CONDITION OF THEIR BANKS AND VICINITY. BY THOMAS ASHE, ESQ. IN THREE VOLUMES. VOL. 1. LC LONDON: PRINTED FOR RICHARD PHILLIPS, BRIDGE-STREET; By John Abraham, Clement's Lane. 1808. F333 A8 224612 15 PREFACE. Travels in America performed in 1806, for the purpose of exploring the rivers Alleghany, Monongahela, Ohio, and Mississippi, and ascertaining the produce and condition of their banks and vicinity. By Thomas Ashe, esq. ... http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbtn.3028a Library of Congress IT is universally acknowledged, that no description of writing comprehends so much amusement and entertainment as well written accounts of voyages and travels, especially in countries little known. If the voyages of a Cook and his followers, exploratory of the South Sea Islands, and the travels of a Bruce, or a Park, in the interior regions of Africa, have merited and obtained celebrity, the work now presented to the public cannot but claim a similar merit. The western part of America, become interesting in every point of view, has been little known, and misrepresented by the few writers on the subject, led by motives of interest or traffic, and has not heretofore been exhibited in a satisfactory manner. Mr. Ashe, the author of the present work, and who has now returned to America, here gives an account every way satisfactory. -

CODE of COLORADO REGULATIONS 2 CCR 406-9 Colorado Parks and Wildlife

DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Colorado Parks and Wildlife CHAPTER W-9 - WILDLIFE PROPERTIES 2 CCR 406-9 [Editor’s Notes follow the text of the rules at the end of this CCR Document.] _________________________________________________________________________ ARTICLE I GENERAL PROVISIONS #900 REGULATIONS APPLICABLE TO ALL WILDLIFE PROPERTIES, EXCEPT STATE TRUST LANDS A. DEFINITIONS 1. “Aircraft” means any machine or device capable of atmospheric flight, including, but not limited to, airplanes, helicopters, gliders, dirigibles, balloons, rockets, hang gliders and parachutes, and any models thereof. 2. “Water contact activities” means swimming, wading (except for the purpose of fishing), waterskiing, sail surfboarding, scuba diving, and other water related activities which put a person in contact with the water (without regard to the clothing or equipment worn). 3. “Youth mentor hunting” means hunting by youths under 18 years of age. Youth hunters under 16 years of age shall at all times be accompanied by a mentor when hunting on youth mentor properties. A mentor must be 18 years of age or older and hold a valid hunter education certificate or be born before January 1, 1949. B. Public Access to State Wildlife Areas 1. Only properties listed in this chapter are open for public access. The Director may open newly acquired properties for public access for a period not to exceed nine (9) months pending adoption of permanent regulations. In addition, the Director may establish and post restrictions based upon consideration of the following criteria: a. The location and size of the area. b. The location, type and condition of roads, vehicle parking areas and the number and type of sanitary facilities available. -

Fuller’S Leadership and Over- Vincent of the Refuge Staff Are Notable for Having Sight Were Invaluable

Acknowledgments Acknowledgments Many people have contributed to this plan over many detailed and technical requirements of sub- the last seven years. Several key staff positions, missions to the Service, the Environmental Protec- including mine, have been filled by different people tion Agency, and the Federal Register. Jon during the planning period. Tom Palmer and Neil Kauffeld’s and Nita Fuller’s leadership and over- Vincent of the Refuge staff are notable for having sight were invaluable. We benefited from close col- been active in the planning for the entire extent. laboration and cooperation with staff of the Illinois Tom and Neil kept the details straight and the rest Department of Natural Resources. Their staff par- of us on track throughout. Mike Brown joined the ticipated from the early days of scoping through staff in the midst of the process and contributed new reviews and re-writes. We appreciate their persis- insights, analysis, and enthusiasm that kept us mov- tence, professional expertise, and commitment to ing forward. Beth Kerley and John Magera pro- our natural resources. Finally, we value the tremen- vided valuable input on the industrial and public use dous involvement of citizens throughout the plan- aspects of the plan. Although this is a refuge plan, ning process. We heard from visitors to the Refuge we received notable support from our regional office and from people who care about the Refuge without planning staff. John Schomaker provided excep- ever having visited. Their input demonstrated a tional service coordinating among the multiple level of caring and thought that constantly interests and requirements within the Service. -

The Buffer Handbook Plant List

THE BUFFER HANDBOOK PLANT LIST Originally Developed by: Cynthia Kuhns, Lake & Watershed Resource Management Associates With funding provided by U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Maine Department of Environmental Protection,1998. Revised 2001 and 2009. Publication #DEPLW0094-B2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements 1 Introductory Information Selection of Plants for This List 1 Plant List Organization & Information 3 Terms & Abbreviations 4 Plant Hardiness Zone Map 5 General Tree & Shrub Planting Guidelines 5 Tips for Planting Perennials 7 Invasive Plants to Avoid 7 Plant Lists TREES 8 (30 to 100 ft.) SHRUBS 14 Small Trees/Large Shrubs 15 (12 to 30 ft.) Medium Shrubs 19 (6 to 12 ft.) Small Shrubs 24 (Less than 6 ft.) GROUNDLAYERS 29 Perennial Herbs & Flowers 30 Ferns 45 Grasses 45 Vines 45 References 49 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Original Publication: This plant list was published with the help of Clean Water Act, Section 319 funds, under a grant awarded to the Androscoggin Valley Soil and Water Conservation District and with help from the Maine Department of Environmental Protection and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Graphics and ‘clip-art’ used in this document came from the University of Wisconsin-Extension and from Microsoft Office 97(Small Business Edition) and ClickArt 97 (Broderbund Software, Inc). This publication was originally developed by Cynthia Kuhns of Lake & Watershed Resource Management Associates. Substantial assistance was received from Phoebe Hardesty of the Androscoggin Valley Soil and Water Conservation District. Valuable review and advice was given by Karen Hahnel and Kathy Hoppe of the Maine Department of Environmental Protection. Elizabeth T. Muir provided free and cheerful editing and botanical advice. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. TOWARD AN UNDERSTANDING OF MIDDLE ARCHAIC PLANT EXPLOITATION: GEOCHEMICAL, MACROBOTANICAL AND TAPHONOMIC ANALYSES OF DEPOSITS AT MOUNDED TALUS ROCKSHELTER, EASTERN KENTUCKY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Katherine Robinson Mickelson, M.A. -

Vegetable Gardening Vegetable Gardening

TheThe AmericanAmerican GARDENERGARDENER® The Magazine of the American Horticultural Society January / February 2009 Vegetable Gardening tips for success New Plants and TTrendsrends for 2009 How to Prune Deciduous Shrubs Sweet Rewards of Indoor Citrus Confidence shows. Because a mistake can ruin an entire gardening season, passionate gardeners don’t like to take chances. That’s why there’s Osmocote® Smart-Release® Plant Food. It’s guaranteed not to burn when used as directed, and the granules don’t easily wash away, no matter how much you water. Better still, Osmocote feeds plants continuously and consistently for four full months, so you can garden with confidence. Maybe that’s why passionate gardeners have trusted Osmocote for 40 years. Looking for expert advice and answers to your gardening questions? Visit PlantersPlace.com — a fresh, new online gardening community. © 2007, Scotts-Sierra Horticulture Products Company. World rights reserved. www.osmocote.com contents Volume 88, Number 1 . January / February 2009 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS 5 NOTES FROM RIVER FARM 6 MEMBERS’ FORUM 8 NEWS FROM AHS Renee’s Garden sponsors 2009 Seed Exchange, Stanley Smith Horticultural Trust grant funds future library at River Farm, AHS welcomes new members to Board of Directors, save the date for the 17th annual National Children & Youth Garden Symposium in July. 42 ONE ON ONE WITH… Bonnie Harper-Lore, America’s roadside ecologist. page 14 44 GARDENER’S NOTEBOOK All-America Selections winners for 2009, scientists discover new plant hormone, NEW PLANTS AND TRENDS FOR 2009 BY DOREEN G. HOWARD 14 Massachusetts Horticultural Society forced Get a sneak peek at some of the exciting plants that will hit the to cancel one of market this year, along with expert insight on garden trends. -

Appendix a List of Preparers and Reviewers

Glossary adfluvial —Referring to fish that live in lakes and no significant impact, aids an agency’s compliance migrate to rivers and streams. with the National Environmental Policy Act when Beyond the Boundaries —National Wildlife Refuge no environmental impact statement is necessary, Association program to expand conservation work and facilitates preparation of a statement when to areas outside national wildlife refuge borders. one is necessary. BRWCA —Bear River Watershed Conservation Area. fluvial —Referring to fish that live in rivers and candidate species —A species of plant or animal for streams. which the USFWS has sufficient information on GCN —(A species of) greatest conservation need. their biological status and threats to propose them HAPET —Habitat and Population Evaluation Team. as endangered or threatened under the Endan- Important Bird Areas Program —A global effort to gered Species Act, but for which development of find and conserve areas that are vital to birds a proposed listing regulation is precluded by other and other biodiversity sponsored by the National higher priority listing activities. Audubon Society. CFR —Code of Federal Regulations. Intermountain West Joint Venture —Diverse partner- CO2 —Carbon dioxide. ship of 18 entities including Federal agencies, conservation easement —A legally enforceable State agencies, nonprofit conservation organiza- encumbrance or transfer of property rights to a tions, and for-profit organizations representing government agency or land trust for the purposes agriculture and industry. IWJV was founded in of conservation. Rights transferred could include 1994 to facilitate bird conservation across the vast the discretion to subdivide or develop land, change 495 million acres of the Intermountain West. -

Maine SCORP 2009-2014 Contents

Maine State Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan 2009-2014 December, 2009 Maine Department of Conservation Bureau of Parks and Lands (BPL) Steering Committee Will Harris (Chairperson) -Director, Maine Bureau of Parks and Lands John J. Daigle -University of Maine Parks, Recreation, and Tourism Program Elizabeth Hertz -Maine State Planning Office Cindy Hazelton -Maine Recreation and Park Association Regis Tremblay -Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Dan Stewart -Maine Department of Transportation George Lapointe -Maine Department of Marine Resources Phil Savignano -Maine Office of Tourism Mick Rogers - Maine Bureau of Parks and Lands Terms Expired: Scott DelVecchio -Maine State Planning Office Doug Beck -Maine Recreation and Parks Association Planning Team Rex Turner, Outdoor Recreation Planner, BPL Katherine Eickenberg, Chief of Planning, BPL Alan Stearns, Deputy Director, BPL The preparation of this report was financed in part through a planning grant from the US Department of the Interior, National Park Service, under the provisions of the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of 1965. Maine SCORP 2009-2014 Contents CONTENTS Page Executive Summary Ex. Summary-1 Forward i Introduction Land and Water Conservation Fund Program (LWCF) & ii Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP) ii State Requirements iii Planning Process iii SCORP’s Relationship with Other Recreation and Conservation Funds iii Chapter I: Developments and Accomplishments Introduction I-1 “Funding for Acquisition” I-1 “The ATV Issue” I-1 “Maintenance of Facilities” I-2 “Statewide Planning” I-4 “Wilderness Recreation Opportunities” I-5 “Community Recreation and Smart Growth” I-7 “Other Notable Developments” I-8 Chapter II: Major Trends and Issues Affecting Outdoor Recreation in Maine A. -

Byword(USA) Chestnut, 2006 • Height 16Hh

Byword(USA) chestnut, 2006 • height 16hh Nearctic - Nearco NORTHERN DANCER Natalma - Native DANCER RACE RECORD Nureyev 1977 Forli - Aristophanes In France, UK, USA and Hong Kong, 7 wins, Special 1600-2000m (from 16 starts; 15 races in Graded and Thong - Nantallah Listed races, for earnings of £699.385). Peintre Celebre Champion Older Horse France 2010 (USA)1994 RAISE A Native - Native DANCER Alydar Timeform 126 – “effective on firm ground as well as soft; Sweet Tooth - On-And-On very best efforts at around 1¼m” Peintre Bleue At 3 WON Prix Pelleas-(L) (2000m) 1987 Habitat - Sir Gaylord 4th Gr2 Prix Guillaume d’Ornano (200m) Petroleuse 4th Gr3 Prix du Prince d’Orange (2000m) Plencia - Le Haar At 4 WON Gr1 Prince Of Wales S. (2000m) RAISE A Native - Native DANCER WON Gr2 Prix du Muguet (1600m) Mr Prospector WON Prix Jacques Laffitte-(L) (1800m) Woodman Gold Digger - Nashua 2nd Gr1 Prix d’Ispahan (1850m) 1983 Buckpasser - Tom Fool 3rd Gr1 Juddmonte Int. S. (2050m) Playmate 4th Gr2 Prix Foy (2400m) Binche (USA) Intriguing - Swaps At 5 WON Gr2 Prix Dollar (1950m) 1999 Blushing Groom - Red God WON Gr3 Prix du Chemin de Fer du Nord (1600m) Rainbow Quest 2nd Gr2 Prix du Muguet (1600m) Binary I Will Follow - Herbager 1993 Nijinsky - NORTHERN DANCER SIRE LINE Balabina PEINTRE CELEBRE – European Horse Of The Year 1997. Peace - Klairon European Champion 3yo, won 5 of 7 starts incl Gr1 GP de Paris, Gr1 Prix du Jockey Club, Gr1 Prix de l’Arc de SALES ANALYSIS 4th dam Triomphe (TFR 137). Sire of sires & broodmare sire of Gr1 BORN colt avg sold SI filly avg sold SI PEACE (66f Klairon): won Blue Seal S.-(L) (only start at 2; TFR winners worldwide. -

Food: Just Grow It!

Food: Just Grow It! Developed with funding support from the Healthy Hawai`i Initiative State of Hawai`i Department of Health __________________________________________________ PROJECT LEADERS: University of Hawaii College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources Cooperative Extension Hawaii State Department of Education Food: Just Grow It! … a supplementary compendium of teaching-learning activities designed to enhance secondary students’ thinking and reasoning skills … __________________________________________________ University of Hawaii College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources Cooperative Extension Hawaii State Department of Education February 2004 FFoooodd:: JJuusstt GGrrooww IItt!! TABLE OF CONTENTS OVERVIEW: 1-6 ACTIVITIES: “Rot for Your Plot” Introduction to Theme Units 7 Creating Soil (Weathering Effects) 9 Hot Spots (Warming and Cooling) 16 Porous or Poor-Us (Soil Characteristics) 25 Taste of Dirt? (pH) 36 Dirt Rich (Soil in the Food Cycle) 45 Under-Cover Critters & Creatures (Composting) 54 Compost Cook-Off (Making Compost) 63 “Why Organic Growing?” Introduction to Theme Units 71 Malama i ka `Aina (Hawaiian Culture) 73 Victory Gardens (WW II Oral History) 83 What Goes Down Stays Around (Water Cycle) 92 OG-What? (Organic Farming Certification) 105 People’s Perceptions (Organic Farming Survey) 114 The Great Debate (Organic vs. High-Intensity) 125 WOG It! (Growing Organically) 133 “Know Your Pests” Introduction to Theme Units 141 Pest-iness (Informal Classification) 143 Least “Wanted” (Local Pest / Disease Problem) -

Division Properties 2 Ccr 406-7

DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Division of Wildlife CHAPTER 9 - DIVISION PROPERTIES 2 CCR 406-7 [Editor’s Notes follow the text of the rules at the end of this CCR Document.] ARTICLE I - GENERAL PROVISIONS #900 REGULATIONS APPLICABLE TO ALL DIVISION PROPERTIES, EXCEPT STATE TRUST LANDS A. Public Access to State Wildlife Areas 1. Only properties listed in this chapter are open for public access. The Director may open newly acquired properties for public access for a period not to exceed nine (9) months pending adoption of permanent regulations. In addition, the Director may establish and post restrictions based upon consideration of the following criteria: a. The location and size of the area. b. The location, type and condition of roads, vehicle parking areas and the number and type of sanitary facilities available. c. The number of users and vehicles the area will tolerate without significant degradation to wildlife resources, and public or private property. d. Opportunity to assure public safety, health and welfare. 2. If a property is opened for public access pursuant to this provision, the property shall be posted with a list of applicable access restrictions. It shall be unlawful for any person or vehicle to enter any such property except in accordance with its posting and the applicable restrictions. B. Prohibited Activities Except as specifically authorized by contractual agreement, official document, public notice, permit or by posted sign, the following activities are prohibited on all lands, waters, the frozen surface of waters, rights- of-way buildings, and other structures or devices owned, operated, or under the administrative control of the Division of Wildlife. -

Recreation and Tourism in Maine's

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons Muskie School Capstones and Dissertations Student Scholarship 5-2014 RECREATION AND TOURISM IN MAINE’S MOOSEHEAD LAKE REGION: A SURVEY OF SUMMER VISITORS Erica Kaufmann University of Southern Maine, Muskie School of Public Service Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/muskie_capstones Part of the Recreation, Parks and Tourism Administration Commons Recommended Citation Kaufmann, Erica, "RECREATION AND TOURISM IN MAINE’S MOOSEHEAD LAKE REGION: A SURVEY OF SUMMER VISITORS" (2014). Muskie School Capstones and Dissertations. 70. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/muskie_capstones/70 This Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Muskie School Capstones and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECREATION AND TOURISM IN MAINE’S MOOSEHEAD LAKE REGION: A SURVEY OF SUMMER VISITORS by Erica Kaufmann Capstone Project Final Report Submitted In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s in Community Planning and Development At the University of Southern Maine Muskie School of Public Service May 2014 Capstone Advisor: Professor Charles Colgan Purpose The area surrounding Moosehead Lake (Maine’s largest) has a long history of outdoor- related tourism. Both Henry David Thoreau and Teddy Roosevelt travelled through the region in the 1800s on their way to (Mount) Katahdin. According to data released by the Maine Office of Tourism, The Maine Highlands, the state-defined tourism region to which Moosehead Lake belongs, received only 10% of all overnight and 8% of all day visitors to Maine during the summer of 2013 (Davidson Peterson Associates, October 2013); yet tourism is considered to be an important part of the local economy.