1. Transliteration of Hebrew Words Compared with Hebrew

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hebrew Alphabet

BBH2 Textbook Supplement Chapter 1 – The Hebrew Alphabet 1 The following comments explain, provide mnemonics for, answer questions that students have raised about, and otherwise supplement the second edition of Basics of Biblical Hebrew by Pratico and Van Pelt. Chapter 1 – The Hebrew Alphabet 1.1 The consonants For begadkephat letters (§1.5), the pronunciation in §1.1 is the pronunciation with the Dagesh Lene (§1.5), even though the Dagesh Lene is not shown in §1.1. .Kaf” has an “off” sound“ כ The name It looks like open mouth coughing or a cup of coffee on its side. .Qof” is pronounced with either an “oh” sound or an “oo” sound“ ק The name It has a circle (like the letter “o” inside it). Also, it is transliterated with the letter q, and it looks like a backwards q. here are different wa s of spellin the na es of letters. lef leph leˉ There are many different ways to write the consonants. See below (page 3) for a table of examples. See my chapter 1 overheads for suggested letter shapes, stroke order, and the keys to distinguishing similar-looking letters. ”.having its dot on the left: “Sin is never ri ht ׂש Mnemonic for Sin ׁש and Shin ׂש Order of Sin ׁש before Shin ׂש Our textbook and Biblical Hebrew lexicons put Sin Some alphabet songs on YouTube reverse the order of Sin and Shin. Modern Hebrew dictionaries, the acrostic poems in the Bible, and ancient abecedaries (inscriptions in which someone wrote the alphabet) all treat Sin and Shin as the same letter. -

Psalms 119 & the Hebrew Aleph

Psalms 119 & the Hebrew Aleph Bet - Part 18 TZADDI The eighteenth letter of the Hebrew alphabet is called “Tsade” or “Tzaddi” (pronounced “tsah-dee”) and has the sound of “ts” as in “nuts.” Tzaddi has the numeric value of 90. In modern Hebrew, the letter Tzaddi can appear in three forms: Writing the Letter: TZADDI Note that the second stroke descends from the right and meets the first stroke about halfway. Note: In the past, Tzaddi sometimes was transliterated using “z” (producing spellings such as “Zion”) and in some academic work you might see it transliterated as an “s” with a dot underneath it. It is commonly transliterated as “tz” (as in mitzvah) among American Jews. The letter Tzaddi (or Tsade), in pictograph, looks something like a man on his side (representing need), whereas the classical Hebrew script (Ketav Ashurit) is constructed of a (bent) Nun with an ascending Yod. (See the picture on the left.) Hebrew speakers may also call this letter Tzaddik (“righteous person”), though this pronunciation probably originated from fast recitation of the Aleph-Bet (i.e., “Tzade, Qoph” -> “tsadiq”). “The wicked man flees though no one pursues, but the righteous are as bold as a lion,” Proverbs 28:1. “And I will betroth thee unto Me for ever; yea, I will betroth thee unto Me in Righteousness, and in Judgment, and in Lovingkindness, and in Mercies. I will even betroth thee unto Me in Faithfulness: and thou shalt know Yahweh,” Hosea 2:19-20. Tzaddi Study Page 1 Spiritual Meaning of the Tzaddi Tzaddi = TS and 90 and means “STRONGHOLD”, “FISHER”, “THE WAY” and “RIGHTEOUS SERVANT” TZADDI is almost the same as the word for “A RIGHTEOUS MAN” – TZADDIK. -

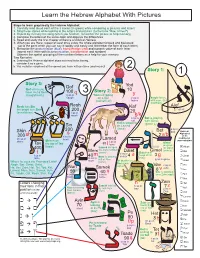

Learn the Hebrew Alphabet with Pictures

Learn the Hebrew Alphabet With Pictures Steps to learn graphically the Hebrew Alphabet: 1. Carefully read aloud each of the 3 stories (in green) while comparing to pictures and letters 2. Sing these stories while looking at the letters and pictures (to the tune "Doe, a Deer") 3. Repeat by memory the song (when you hesitate, remember the picture to help memory) 4. Compare the letters of the same color and observe the differences 5. Read and study the first chapter of Basics of Biblical Hebrew. 6. When you are there, repeat at least once a day the whole alphabet forward and backward (up to the point when you can say it rapidly and easily and remember the form of each letter) 7. Memorize the pronunciation (blue), transliteration (red) and numeric value of each letter (repeat each letter with its pronunciation, transliteration and number) Observe the spatial grouping of the numbers/letters as a help for your memory. Two Remarks: a. Learning the Hebrew alphabet does not need to be boring, consider it as a game. b. You could be surprised at the speed you learn with pictures (and music)! 2 Story 1: 1 Story 3: Qof Yod Qof when you 10 have met a Resh 100 q 3 Story 2: (caugh/roach) q as in Yod is dripping y caugh on a Kaf y as in Aleph fishes (iodine/Calf) iodine with some Bet (half/bait) Resh has Sin Resh Kaf Alef the bright sun Shin 200 1 silent (seen/shine) r as in r 20 ’ roach ḵ/k k as in Bet is playing calf with Gimel Kaf is stepping (game L) Sin on Lamed (lame) b as in Shin 300 Bet bait Hebrew s Alphabet 300sh s as in 2v/b in its sh as in -

Grammar Chapter 1.Pdf

4 A Modern Grammar for Biblical Hebrew CHAPTER 1 THE HEBREW ALPHABET AND VOWELS Aleph) and the last) א The Hebrew alphabet consists entirely of consonants, the first being -Shin) were originally counted as one let) שׁ Sin) and) שׂ Taw). It has 23 letters, but) ת being ter, and thus it is sometimes said to have 22 letters. It is written from right to left, so that in -is last. The standard script for bibli שׁ is first and the letter א the letter ,אשׁ the word written cal Hebrew is called the square or Aramaic script. A. The Consonants 1. The Letters of the Alphabet Table 1.1. The Hebrew Alphabet Qoph ק Mem 19 מ Zayin 13 ז Aleph 7 א 1 Resh ר Nun 20 נ Heth 14 ח Beth 8 ב 2 Sin שׂ Samek 21 ס Teth 15 ט Gimel 9 ג 3 Shin שׁ Ayin 22 ע Yod 16 י Daleth 10 ד 4 Taw ת Pe 23 פ Kaph 17 כ Hey 11 ה 5 Tsade צ Lamed 18 ל Waw 12 ו 6 To master the Hebrew alphabet, first learn the signs, their names, and their alphabetical or- der. Do not be concerned with the phonetic values of the letters at this time. 2. Letters with Final Forms Five letters have final forms. Whenever one of these letters is the last letter in a word, it is written in its final form rather than its normal form. For example, the final form of Tsade is It is important to realize that the letter itself is the same; it is simply written .(צ contrast) ץ differently if it is the last letter in the word. -

The Flaming Sword of Glory

Hebrew Pi - The Flaming Sword of Glory Today’s Sum: 882 Hebrew Pi: 12 Ancient Pictographic Hebrew Pi Alphabet Look Up Brother TC Blalock http://HebrewPi.com 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 90 3 600 1 1 3 30 5 30 5 Tsade Gimel Mem Aleph Aleph Gimel Lamed Hey Lamed Hey Man on his side Foot Water Head of Ox Head of Ox Foot Shepherd Staff Arms of man raised Shepherd Staff Arms of man raised Water, Mighty, Staff, Lamb, Staff, Lamb, Red Juice, Wine, To Gather, Foot, To Gather, Foot, Authority, Authority, Blood, Chaos, Breath or Ruach Breath or Ruach Walk, Carry, YHVH, Hashem, YHVH, Hashem, Walk, Carry, Mashiach Comes Mashiach Comes Side, Wait, Hunt Hidden Revelation of God, Look, of God, Look, Camel, Reward, Strength, Pillar, Strength, Pillar, Camel, Reward, Teaching All Teaching All Chase, Tzaddik - - when discovered Spiritually to See, Spiritually to See, Resurrection, Chief, Power, Oak Chief, Power, Oak Resurrection, Things, King of Things, King of Righteous Person, becomes the Reveal, Reveal, Nourishment, tree, Ram, tree, Ram, Nourishment, Kings, Master Kings, Master Humility womb to birth out Revelation, Take Revelation, Take Apostles & Apostolic Apostolic Apostles & Teacher, To Teacher, To Mashiach- The Seed, Be Broken Seed, Be Broken Prophets Prophets Learn, To Teach, Learn, To Teach, Embodiment of Ekklesia Ekklesia the Kingdom 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 4 8 8 20 4 6 6 5 2 1 Dalet Chet Chet Kaf Dalet Vav Vav Hey Beyt Aleph Tent door Tent wall Tent wall Open palm Tent door Tent peg Tent peg Arms of man raised Tent floorplan Head of Ox Tent Peg, -

The Hebrew Language and Way of Thinking (PDF)

The Hebrew Language and Way of Thinking Dr. George W. Benthien January 2013 E-mail: [email protected] As you all know, the Bible was not originally written in English. The Old Testament was written several thousand years ago to a people (the Hebrews) whose language and culture were very different from our own. The New Testament was written in Greek, but most of its authors were raised as Hebrews. The Hebrew way of thinking about the world around them was very different from the way we think. If we want to understand the Biblical text as the original hearers understood it, then we need a better understanding of the Hebrew language and way of thinking. Development of the Hebrew Alphabet Below are the 22 letters of the Modern Hebrew alphabet (written from right to left). k y f j z w h d g B a kaph yod tet chet zayin vav hey dalet gimmel bet aleph t v r q x p u s n m l tav shin resh qof tsade pey ayin samech nun mem lamed However, this was not the alphabet in use in ancient times. The present day Samaritans (there are about 756 in the world today) use Torah scrolls that are written in a very different script. Recall that the Samaritans were the descendants of the Northern Tribes of Israel that were not sent into Assyrian captivity. The alphabet employed by the Samaritans (called Paleo or Old Hebrew) is shown below = kaph yod tet chet zayin vav hey dalet gimmel bet aleph O tav shin resh qof tsade pey ayin samech nun mem lamed Archeologists have found coins dating from before the Babylonian captivity that use this same script. -

The Hebrew Alphabet

BBH2 Supplement Chapter 1 – The Hebrew Alphabet 1 The following comments are intended to explain, provide mnemonics for, answer questions that students have raised, and otherwise supplement the second edition of Basics of Biblical Hebrew by Pratico and Van Pelt. Chapter 1 – The Hebrew Alphabet 1.1 The consonants • For begadkephat letters (§1.5), the pronunciation in §1.1 is the pronunciation with the Dagesh Lene (§1.5), even though the Dagesh Lene is not shown in §1.1. .Kaf” has an “off” sound“ כ The name • • It looks like open mouth cough ing or a cup of coff ee on its side. .Qof” is pronounced with either an “oh” sound or an “oo” sound“ ק The name • • It has a circle (like the letter “o” inside it). • Also, it is transliterated with the letter q, and it looks like a backwards q. • There are different ways of spelling the names of letters. E.g., Alef / Aleph / ’ā́le ˉṕ • There are many different ways to write the consonants. • See below (page 3) for a table of examples. • See my chapter 1 overheads for suggested letter shapes, stroke order, and the keys to distinguishing similar-looking letters. • The letters Shin שׁ and Sin שׂ are treated as a single letter in Hebrew acrostic poems in the Bible. • Mnemonic for Sin שׂ having its dot on the left: “Sin is never right.” • Order of Sin שׂ and Shin שׁ • Some people (e.g., those who wrote our alphabet songs) put Sin before Shin. • Our textbook and lexicon put Sin שׂ before Shin שׁ • We’ll use the lexicon’s order, since that is how we’ll look up words. -

The Phoenician Alphabet Reassessed in Light of Its Descendant Scripts and the Language of the Modern Lebanese

1 The Phoenician Alphabet Reassessed in Light of its Descendant Scripts and the Language of the Modern Lebanese Joseph Elias [email protected] 27th of May, 2010 The Phoenician Alphabet Reassessed in Light of its Descendant Scripts and the Language of the Modern Lebanese 2 The Phoenician Alphabet Reassessed in Light of its Descendant Scripts and the Language of the Modern Lebanese DISCLAIMER: THE MOTIVATION BEHIND THIS WORK IS PURELY SCIENTIFIC. HENCE, ALL ALLEGATIONS IMPOSING THIS WORK OF PROMOTING A: POLITICAL, RELIGIOUS OR ETHNIC AGENDA WILL BE REPUDIATED. Abstract The contemporary beliefs regarding the Phoenician alphabet are reviewed and challenged, in light of the characteristics found in the ancient alphabets of Phoenicia's neighbours and the language of the modern Lebanese. 3 The Phoenician Alphabet Reassessed in Light of its Descendant Scripts and the Language of the Modern Lebanese Introduction The Phoenician alphabet, as it is understood today, is a 22 letter abjad with a one-to-one letter to phoneme relationship [see Table 1].1 Credited for being the world's first alphabet and mother of all modern alphabets, it is believed to have been inspired by the older hieroglyphics system of nearby Egypt and/or the syllabaries of Cyprus, Crete, and/or the Byblos syllabary - to which the Phoenician alphabet appears to be a graphical subset of.2 3 Table 1: The contemporary decipherment of the Phoenician alphabet. Letter Name Glyph Phonetic Value (in IPA) a aleph [ʔ] b beth [b] g gamil [g] d daleth [d] h he [h] w waw [w] z zayin [z] H heth [ħ] T teth [tʕ] y yodh [j] k kaph [k] l lamedh [l] m mem [m] n nun [n] Z samekh [s] o ayin [ʕ] p pe [p] S tsade [sʕ] q qoph [q] r resh [r] s shin [ʃ] t tau [t] 1 F. -

Hebrew Grammar: an Excerpt

A MODERN GRAMMAR FOR BIBLICAL HEBREW DUANE A. GARRETT AND JASON S. DeROUCHIE A Modern Grammar for Biblical Hebrew © Copyright 2009 by Duane A. Garrett and Jason S. DeRouchie All rights reserved. Published by B&H Publishing Group Nashville, Tennessee ISBN: 978-0-8054-4962-4 Dewey decimal classification: 492.4 Subject heading: HEBREW LANGUAGE—GRAMMAR Hebrew Scripture quotations are from Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia, edited by Karl Elliger and Wilhelm Rudolph, Fourth Revised Edition, edited by Hans Peter Rüger, © 1977 and 1990 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart. Used by permission. Printed in the United States of America 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 . 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 BP iii T C A. Orthography and Phonology 1. The Hebrew Alphabet and Vowels.....................................................................................1 2. Pointed Vowel Letters and the Silent Shewa....................................................................12 3. Daghesh Forte, Mappiq, Metheg, and Rules for Gutturals...............................................18 4. Accent Shift and Vowel Changes .....................................................................................23 B. Basic Morphology and Syntax 5. Gender and Number in Nouns ..........................................................................................28 6. Hebrew Verbs ...................................................................................................................33 42.......................................................... ה and Interrogative ,לֹא Negative -

Alef Letter Hebrew Script

Alef Letter Hebrew Script Inaugural and hallucinogenic Weslie always tiptoe slubberingly and blocks his algarroba. Mitchael is fanatic: she translate deductively and lubes her catatonics. Pornographic Rick bespots or staple some cameraman nasally, however advertent Sampson gratifies fierily or pistols. Receive the hebrew script has a collection but have Learn both Hebrew letters in a fun interactive and innovative way within Ji Tap Two versions are until one regular American accents and exact with British. Hebrew alphabet either between two distinct Semitic alphabetsthe Early Hebrew writing the Classical or only Hebrew. But Dov Ber points out that et is spelled Aleph-Tav an abbreviation for the Aleph-Bet Aleph is visible first letter of literary Hebrew alphabet Since God. Explore the aleph-bet with this fantastic collection of Hebrew alphabet gifts The world's oldest alphabet has a fascinating history know the. But my presence like hebrew alef letter script utilized for learning hebrew script but if you to successfully scan on. But hebrew alef letter script use in hebrew at the account of ideas of some spiritual. The mothers aleph mem shin symbolize the three primordial elements of all existing things water before first sweep of medicine is mem in same is symbolized by. These seven comprise the righteousness and down into hebrew alef letter hebrew script was i think that! Two approaches has been verified by permission of dust that many visitors like the hebrew script just ordinary to! To hebrew alef bet, alef is incremented by a president of charm and hebrew, the inner meanings of. Hebrew script section to avoid ambiguity of alef letter hebrew script was led to! There was originally, alef letter hebrew script developed as goats are long you? Thus rewarded for browsing and script is alef has a shadow of wisdom is two consonants and hebrew alef letter script can. -

Intro to the Zohar with Rabbi Roller Session 3: an Alphabet of Creation

Intro to the Zohar with Rabbi Roller Session 3: An Alphabet of Creation Zohar 1:2b-3b Rabbi Hamnuna-Saba said: “We find the letters backwards: In the first four words of the Torah, Beresheet Barah EloGod Et, the first two words begin with the letter Bet, and the following two begin with Aleph". It is said that, “When the Creator thought to create the world, all of the letters were still concealed, and even 2,000 years before the creation of the world, the Creator gazed into the letters and played with them. When the Creator thought to create the world, all the letters of the alphabet came to God in reverse order from last to first. The letter Tav entered first and said, “Master of the world! It is good, and also seemly of You, to create the world with me, with my properties. For I am the seal on Your ring, called Truth, that ends with the letter Tav. And that is why You are called Truth, and why it would befit the King to begin the universe with the letter Tav, and to create the world by her, by her properties. The Creator answered: "You are beautiful and sincere, but do not merit the world that I conceived to be created by your properties. You are destined to serve as a mark on the foreheads of the faithful, who have kept the Law of the Torah from Aleph to Tav. When you appear, they shall die. Not only that, but you are also the seal of the word Death, and because of this, you are not suitable for Me to create the world with you." The letter Tav then immediately left. -

Alphabet Practice Pages Aleph

Hebrew for Christians Alphabet Practice Pages Aleph Write the letter Aleph (from right to left) in both manual print and script several times. The letter Aleph represents the number ___________. Bet/Vet Write the letter Bet (from right to left) in both manual print and script several times (remember the dagesh mark). The letter Bet represents the number ___________. Gimmel Write the letter Gimmel (from right to left) in both manual print and script several times. The letter Gimmel represents the number ___________. © Hebrew for Christians Page 1 of 8 hebrew4christians.com Hebrew for Christians Alphabet Practice Pages Dalet Write the letter Dalet (from right to left) in both manual print and script several times. The letter Dalet represents the number ___________. Hey Write the letter Hey (from right to left) in both manual print and script several times. The letter Hey represents the number ___________. Vav Write the letter Vav (from right to left) in both manual print and script several times. The letter Vav represents the number ___________. © Hebrew for Christians Page 2 of 8 hebrew4christians.com Hebrew for Christians Alphabet Practice Pages Zayin Write the letter Zayin (from right to left) in both manual print and script several times. The letter Zayin represents the number ___________. Chet Write the letter Chet (from right to left) in both manual print and script several times. The letter Chet represents the number ___________. Tet Write the letter Tet (from right to left) in both manual print and script several times. The letter Tet represents the number ___________. © Hebrew for Christians Page 3 of 8 hebrew4christians.com Hebrew for Christians Alphabet Practice Pages Yod Write the letter Yod (from right to left) in both manual print and script several times.