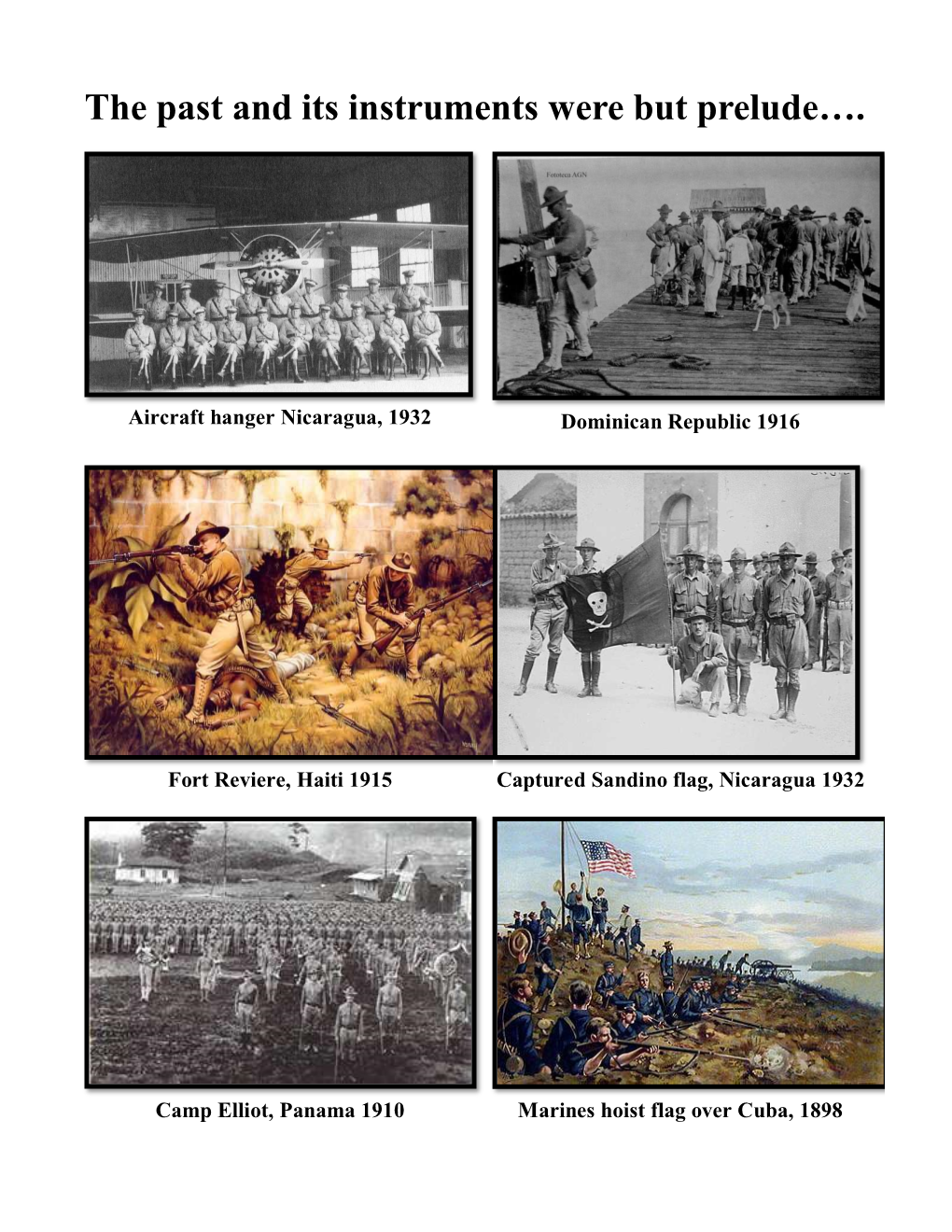

Banana Wars" Part One

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia

Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia Geographically, Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam are situated in the fastest growing region in the world, positioned alongside the dynamic economies of neighboring China and Thailand. Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia compares the postwar political economies of these three countries in the context of their individual and collective impact on recent efforts at regional integration. Based on research carried out over three decades, Ronald Bruce St John highlights the different paths to reform taken by these countries and the effect this has had on regional plans for economic development. Through its comparative analysis of the reforms implemented by Cam- bodia, Laos and Vietnam over the last 30 years, the book draws attention to parallel themes of continuity and change. St John discusses how these countries have demonstrated related characteristics whilst at the same time making different modifications in order to exploit the strengths of their individual cultures. The book contributes to the contemporary debate over the role of democratic reform in promoting economic devel- opment and provides academics with a unique insight into the political economies of three countries at the heart of Southeast Asia. Ronald Bruce St John earned a Ph.D. in International Relations at the University of Denver before serving as a military intelligence officer in Vietnam. He is now an independent scholar and has published more than 300 books, articles and reviews with a focus on Southeast Asia, -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to loe removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI* Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 WASHINGTON IRVING CHAMBERS: INNOVATION, PROFESSIONALIZATION, AND THE NEW NAVY, 1872-1919 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctorof Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Stephen Kenneth Stein, B.A., M.A. -

“What Are Marines For?” the United States Marine Corps

“WHAT ARE MARINES FOR?” THE UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation by MICHAEL EDWARD KRIVDO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2011 Major Subject: History “What Are Marines For?” The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era Copyright 2011 Michael Edward Krivdo “WHAT ARE MARINES FOR?” THE UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation by MICHAEL EDWARD KRIVDO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Joseph G. Dawson, III Committee Members, R. J. Q. Adams James C. Bradford Peter J. Hugill David Vaught Head of Department, Walter L. Buenger May 2011 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT “What Are Marines For?” The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era. (May 2011) Michael E. Krivdo, B.A., Texas A&M University; M.A., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Joseph G. Dawson, III This dissertation provides analysis on several areas of study related to the history of the United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era. One element scrutinizes the efforts of Commandant Archibald Henderson to transform the Corps into a more nimble and professional organization. Henderson's initiatives are placed within the framework of the several fundamental changes that the U.S. Navy was undergoing as it worked to experiment with, acquire, and incorporate new naval technologies into its own operational concept. -

Thompson Brochure 9Th Edition.Indd

9th Edition Own A Piece Of American History Thompson Submachine Gun General John T. Thompson, a graduate of West Point, began his research in 1915 for an automatic weapon to supply the American military. World War I was dragging on and casualties were mounting. Having served in the U.S. Army’s ordnance supplies and logistics, General Thompson understood that greater fi repower was needed to end the war. Thompson was driven to create a lightweight, fully automatic fi rearm that would be effective against the contemporary machine gun. His idea was “a one-man, hand held machine gun. A trench broom!” The fi rst shipment of Thompson prototypes arrived on the dock in New York for shipment to Europe on November 11, 1918 the day that the War ended. In 1919, Thompson directed Auto-Ordnance to modify the gun for nonmilitary use. The gun, classifi ed a “submachine gun” to denote a small, hand-held, fully automatic fi rearm chambered for pistol ammunition, was offi cially named the “Thompson submachine gun” to honor the man most responsible for its creation. With military and police sales low, Auto-Ordnance sold its submachine guns through every legal outlet it could. A Thompson submachine gun could be purchased either by mail order, or from the local hardware or sporting goods store. Trusted Companion for Troops It was, also, in the mid ‘20s that the Thompson submachine gun was adopted for service by an Dillinger’s Choice offi cial military branch of the government. The U.S. Coast Guard issued Thompsons to patrol While Auto-Ordnance was selling the Thompson submachine gun in the open market in the ‘20s, boats along the eastern seaboard. -

The Pistol in British Military Service During the Great War

Centre for First World War Studies The Pistol in British Military Service during the Great War A dissertation submitted by David Thomas (SRN 592736) in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MA in British First World War Studies September 2010 1 Contents Introduction 3 Current Literature Review 3 Questions to be Addressed 5 Chapter One-Use and Issue 6 Chapter Two-Technique and Training 11 Accessories 14 Ammunition 16 Chapter Three-Procurement 18 History 18 Army Procurement 19 Royal Navy Procurement 23 Private Purchase 24 Overall Numbers 26 Conclusions. 26 Bibliography 28 Appendix 33 Acknowledgements 37 All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the written permission of the author. 2 Introduction The British military services made considerable use of pistols during the Great War but it is evident that there is widespread ignorance and poor literary coverage of the weapons and their use. It is proposed to examine the pistol in British military service in the Great War, covering issue and use, technique and training, and procurement. Approximately half a million pistols were procured during the war, making it one of the numerically most widely issued weapons. A number of Corps, including the Machine Gun Corps, Tank Corps, and Royal Flying Corps were issued pistols as personal weapons, as well as extensive distribution in other arms. It is known that pistol use was widespread in trench warfare and critical on occasions. Decorations, including several Victoria Crosses, are recorded as being won by men using them aggressively. -

The Impact of the Great War on Marines in Hispaniola, 1917-1919

The Impact of the Great War on Marines in Hispaniola, 1917-1919 Temple University 2014 James A. Barnes Graduate Student History Conference Mark R. Folse, PhD. Student Department of History The University of Alabama [email protected] World War I dominates the history of American military institutions from 1917-1919. Scholarship on the U.S. Marine Corps is no different and many have argued that Marine actions in the spring and summer of 1918 against the last German offensive on the Western Front served as the coming of age story for Corps.1 Marines came out of the war with a new and improved force structure, a population of officers and men experienced in modern war, and, perhaps even more significantly, a sense of vindication. The opportunity to prove their worth to the other services and to the American people in a large war arrived and they succeeded. Relatively little scholarly attention, however, has been given to how the Great War affected Marines who did not fight in France, especially the ones deployed to Hispaniola. Therefore, the full extent of the Great War’s impact on the Marine Corps remains largely neglected. In several similar and significant ways the Great War affected, often negatively, the Marine missions in Haiti and the Dominican Republic. The war damaged morale among many Marines, especially among the brigade commanders like Smedley Butler and George C. Thorpe who preferred very much to transfer to France rather than remain at their posts in Haiti and Santo Domingo respectively. Once the war started the Department of the Navy pulled experienced 1 Allan R. -

General Assembly Distr.: Middle School Eleventh Session XX March 2018 Original: English

Montessori Model United Nations A/C.6/12/BG-79 General Assembly Distr.: Middle School Eleventh Session XX March 2018 Original: English Sixth Committee – Legal This group focuses on legal questions. The UN wants all states to agree to international laws. This can happen if they make them together. They also want to make sure people know the laws. This can happen if they are written down and published. This makes it easier for states to work together. It also stops wars from happening. They also ask states to make laws to protect citizens. Every year the General Assembly gives this group a discussion list. If the legal question is difficult or complex this group asks for help from the International Law Commission. This committee has a tradition of consensus. States reach agreement without having to take a vote. This makes sense because if you want everybody to follow a law they should agree it is a good idea. This group works closely with the International Law Commission. They passed resolutions on international terrorism, human cloning, and taking hostages. Agenda Item 79 – Diplomatic Protection A lot of people confuse Diplomatic Protection with Diplomatic Immunity. Diplomatic Immunity is given to diplomats of a government who enter (with permission) into another country in order to do work for their own country. An ambassador or anybody who is sent from their home country to work at an embassy has Diplomatic Immunity. This law allows diplomats to do their Jobs in safety. They do not have to fear being Jailed or mistreated by the country they are working in. -

Twilight 2000

TWILIGHT 2000 Twilight 2000 is a Role playing game set in a fictional future, one where World war 3 began in the late 1990's and eventually slipped into a nuclear exchange changing society as we know it. The players assume the roles of survivors trying to live through the aftermath of the war. Twilight 2000 was published in the mid 1980's by Game Designers Workshop who unfortunately closed their doors in the early 1990's. The copyright was purchased by Tantalus, Inc but there are no stated plans to revive the game. Despite the lack of any new material from a publisher the game continues to expand through the players on websites such as this. This is my contribution to the game, this site will be in a constant state of change, I plan to add material as I get it finished. This will include new equipment, optional rules, alternate game backgrounds and other material as it accumulates, currently I am working on source material for a World war 2 background, but I also have been completing some optional rules of my own as well as modern equipment. For other perspectives on Twilight 2000 visit the links listed at the bottom of this page. Twilight 2000 World war 2 material World war 2 source book Twilight 2000 Modern equipment Modern equipment Optional rules for Twilight 2000 Fire Links to other Twilight 2000 pages Antennas T2K Page: Focusing on Sweden's forces, equipment and background, also includes archives of discontinued sites and web discussions. The Dark place: Includes material for several RPG's including Twilight 2000 and Behind Enemy Lines. -

GUNS Magazine April 1959

ONE SCOPE """ ALL GAME! B&L BALvar 8 Variable Power 2~x to 8x It's the most wanted scope on the market-the onl y multi-purpose scope of its k ind providing year 'round hunting through an excellent choice of low D&L DALVar 0 Variable Power 2~x to 8x It's the most wanted scope on the market-the onl y multi-purpose scope of its k ind providing year 'round hunting through an excellent choice of low powers for big game and high powers (up to 8 X) for varmints. And there's '[----- "'""" no change in reticle size, eye relief, focus or point of impact as power is changed! BALvar 8 is rugged ... designed and built to take hard punishment during hunting trips. All adjustments are made externally in the mount-no delicate internal parts to jar loose. With its lifetime guarantee, the BALvar 8 is your best buy ... it's several scopes in one for all hunters! Price $99.50. E9 INTERCHANGEABLE-RIFLE TO RIFLE! E9 WIDE FIELD! The wide field at 2Y2x Put B&L mounts on your favorite hunt (4 0 ' at 100 yds.) helps the hunter in ing rifl es; zero your BALvar 8 on these tracking a moving target-"c!ose in" o n mounts . .. once your mounts are game with desired power and shoot zeroed, BALvar 8 can be transferred with accuracy. from mount to mount in seconds, lock ing in perfect zero every time! E9 SHOOT NOW-PAY LATER! Buy your BAL var 8 or any other fine B&L scope E9 SAFETY FEATURE-VARIABLE POWER! no w on the convenient time payment When hunting, use higher power for plan. -

Mg 34 and Mg 42 Machine Guns

MG 34 AND MG 42 MACHINE GUNS CHRIS MC NAB © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com MG 34 AND MG 42 MACHINE GUNS CHRIS McNAB Series Editor Martin Pegler © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 DEVELOPMENT 8 The ‘universal’ machine gun USE 27 Flexible firepower IMPACT 62 ‘Hitler’s buzzsaw’ CONCLUSION 74 GLOSSARY 77 BIBLIOGRAPHY & FURTHER READING 78 INDEX 80 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com INTRODUCTION Although in war all enemy weapons are potential sources of fear, some seem to have a deeper grip on the imagination than others. The AK-47, for example, is actually no more lethal than most other small arms in its class, but popular notoriety and Hollywood representations tend to credit it with superior power and lethality. Similarly, the bayonet actually killed relatively few men in World War I, but the sheer thought of an enraged foe bearing down on you with more than 30cm of sharpened steel was the stuff of nightmares to both sides. In some cases, however, fear has been perfectly justified. During both world wars, for example, artillery caused between 59 and 80 per cent of all casualties (depending on your source), and hence took a justifiable top slot in surveys of most feared tools of violence. The subjects of this book – the MG 34 and MG 42, plus derivatives – are interesting case studies within the scale of soldiers’ fears. Regarding the latter weapon, a US wartime information movie once declared that the gun’s ‘bark was worse than its bite’, no doubt a well-intentioned comment intended to reduce mounting concern among US troops about the firepower of this astonishing gun. -

The Small Wars Manual: a Lasting Legacy in Today’S Counter- Insurgency Warfare

The Small Wars Manual: A Lasting Legacy in Today’s Counter- insurgency Warfare Thomas Griffith ___________________________________________________________ August 1930—While New York Supreme Court judge Joseph Crater went missing in Manhattan, Betty Boop made her debut, and All Quiet on the Western Front premiered at theaters in Wilmington, North Carolina, the rainy season settled into the jungles of Nicaragua. A band of no more than 40 men, U.S. Marines and native Guardia Nacional troops, patrolled just outside of Malacate.1 Company M marched for days under orders to locate and destroy bandits following Augusto C. Sandino, a former Nicaraguan presidential candidate. They traveled by foot, averaging 18 to 30 miles a day, using only mules to haul their gear, which was packed lighter to avoid detection.2 Intelligence reached the unit describing a bandit troop of horse thieves, so they went on the pursuit. The mud was a thick slop and fatigued the men, but the situation was worse for the bandits. Their horses tired easily in the sludge and had to be rested every third day.3 By August 19, less than a week later, Company M caught up to the bandits, but they were already lying in an ambush. About 150 Sandinistas opened fire from the side of a hill. The company’s commander, Captain Lewis B. Puller, led his patrol through the kill zone then turned to flank the ambush at full speed; however, the bandits already started to retreat. The company only killed two of its quarry, but they captured stolen items including eighty horse, mules, saddles, and corn.4 Puller was recommended for his first Navy Cross, the Department of the Navy’s second highest decoration, preceded only by the Medal of Honor. -

Part II (A) Non-Russian Motorcycles with Machine Guns and MG Mounts

PartPart IIII (A)(A) NonNon--RussianRussian MotorcyclesMotorcycles withwith MachineMachine GunsGuns andand MGMG MountsMounts ErnieErnie FrankeFranke Rev.Rev. 1:1: 05/201105/2011 [email protected]@tampabay.rr.com NonNon--RussianRussian MotorcyclesMotorcycles byby CountryCountry • Universal Role of Adding Machine Guns to Motorcycles • American –Indian –Harley-Davidson –Kawasaki • British –Clyno –Royal Enfield –Norton • Danish –Harley-Davidson –Nimbus • Dutch –Swiss Motosacoche –FN Products (Belgium) –Norton –Harley-Davidson • German –BMW –Zundapp • Italy –Moto Guzzi • Chinese –Chang Jiang • Russian –Ural Man has been trying to add a machine gun to a sidecar for many years in many countries. American: Browning 1895 on a Harley-Davidson Sidecar (browningmgs.com) World War-One (WW-I) machine gun mounted on Indian motorcycle with sidecar. American:American: MotorcycleMotorcycle MachineMachine GunGun (1917)(1917) (www.usmilitariaforum.com) World War-One (WW-I) machine gun mounted on a Indian motorcycle with sidecar. American:American: BenetBenet--MercieMercie mountedmounted onon IndianIndian (forums.gunboards.com) It is hard to see how any accuracy could be achieved while on the move, so the motorcycle had to be stopped before firing. American:American: MilitaryMilitary IndianIndian SidecarsSidecars (browningmgs.com) One Indian has the machine gun, the other has the ammo. American: First Armored Motor Battery of NY and Fort Gordon, GA (www.motorcycle-memories.com and wikimedia.org) (1917) The gun carriage was attached as a trailer to a twin-cylinder motorcycle. American:American: BSABSA (info.detnews.com) World War-Two (WW-II) 50 cal machine gun mounted on a BSA motorcycle with sidecar. American:American: HarleyHarley--DavidsonDavidson WLAWLA ModelModel Ninja Warriors! American:American: "Motorcycle"Motorcycle ReconnaissanceReconnaissance TroopsTroops““ byby RolandRoland DaviesDavies Determined-looking motorcycle reconnaissance troops head towards the viewer, with the first rider's Thompson sub machine-gun in action.