A History of First Nations in the Fraser River Basin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fraser River from Source to Mouth

FRASER RIVER FROM SOURCE TO MOUTH September 5, 2017 - 11 Days Fares Per Person: $3395 double/twin $4065 single $3210 triple > Please add 5% GST. Early Bookers: $160 discount on first 12 seats; $80 on next 8 > Experience Points: Earn 76 points from this tour. Redeem 76 points if you book by July 5. Includes Flight from Victoria to Kelowna St. John the Divine Church in Yale Coach transportation for 10 days Harrison Hot Springs pools 10 nights of accommodation & hotel taxes Copper Room music & dancing with Jones Boys Helicopter to the source of the Fraser River Fraser River Safari boat excursion Fraser River raft float trip (no white water) Paddlewheeler cruise from New Westminster Huble Homestead tour to the mouth of the Fraser River Farwell Canyon and pictographs Gulf of Georgia Cannery National Historic Site Cariboo Chilcotin Museum Transfer from New Westminster to Victoria Hat Creek Historic Ranch and roadhouse tour Knowledgeable tour director Hell’s Gate Airtram Luggage handling at hotels Alexandra Suspension Bridge 21 meals: 8 breakfasts, 9 lunches, 4 dinners Activity Level This is a unique tour with lots of activity and time outdoors while you experience many aspects of the Fraser River. The trip to the source of the Fraser requires getting in and out of a helicopter, and walking about ½ km in an alpine meadow at 2,000 metres altitude. On other days, you are boarding a large raft and two boats. Walks in- clude Farwell Canyon pictographs, Alexandra Bridge, and the boat dock to Kilby Store. This tour has activity ranging from somewhat rigorous to sedentary. -

Ecosystem Status and Trends Report for the Strait of Georgia Ecozone

C S A S S C C S Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Secrétariat canadien de consultation scientifique Research Document 2010/010 Document de recherche 2010/010 Ecosystem Status and Trends Report Rapport de l’état des écosystèmes et for the Strait of Georgia Ecozone des tendances pour l’écozone du détroit de Georgie Sophia C. Johannessen and Bruce McCarter Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Institute of Ocean Sciences 9860 W. Saanich Rd. P.O. Box 6000, Sidney, B.C. V8L 4B2 This series documents the scientific basis for the La présente série documente les fondements evaluation of aquatic resources and ecosystems scientifiques des évaluations des ressources et in Canada. As such, it addresses the issues of des écosystèmes aquatiques du Canada. Elle the day in the time frames required and the traite des problèmes courants selon les documents it contains are not intended as échéanciers dictés. Les documents qu’elle definitive statements on the subjects addressed contient ne doivent pas être considérés comme but rather as progress reports on ongoing des énoncés définitifs sur les sujets traités, mais investigations. plutôt comme des rapports d’étape sur les études en cours. Research documents are produced in the official Les documents de recherche sont publiés dans language in which they are provided to the la langue officielle utilisée dans le manuscrit Secretariat. envoyé au Secrétariat. This document is available on the Internet at: Ce document est disponible sur l’Internet à: http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas/ ISSN 1499-3848 (Printed / Imprimé) ISSN 1919-5044 (Online / En ligne) © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2010 © Sa Majesté la Reine du Chef du Canada, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Highlights 1 Drivers of change 2 Status and trends indicators 2 1. -

Tl'azt'en Nation

Tl’azt’en Nation PO Box 670, Fort St James, B.C. V0J1P0 Phone: 250-648-3212Fax: 250-648-3250 JOIN OUR DYNAMIC TEAM WE ARE HIRING A COMMUNITY HEALTH NURSE Full Time - Contract The Tl’azt’en Nation are a people of the Dakelh, Carrier language group of north central British Columbia. Binche is 30 km north of Fort St James and Tachie is 50 km north of Fort St James; both communities are on the eastern shores of Nakal Bun, Stuart Lake. Dzitlainli is further north on Tremblaur Lake and is seasonally populated. There are over 1,500 Tl’azt’en members with approximately 600 on reserve. The health center provides services to 3 communities, Tachie, Binche and Dzitlainli (Middle River) with a satellite office in Binche. Tl’azt’en First Nation and its employees are committed to a proactive holistic approach to health and wellness, and to the delivery of services which are sustainable and honor the customs and traditions of our community. Title Community Health Nurse - Health Centre Job Duration Permanent & Temporary Reporting to: Director Health Services Position Summary We currently have vacant position in our Community Health Center: Our ideal candidate has a comprehensive range of core nursing functions and services in our community in program areas of community and/or public heath, primary care, and on occasion home care through promotion and maintenance of the health of individuals, families, groups, communities, and populations that value the principles of primary health care and focus on promoting health, preventing disease and injury, prevention against addiction, protecting population health, as well as a focus on curative, urgent and emergent care, rehabilitation, and supportive or palliative care. -

Indigenous Experiences Guide to British Columbia

Indigenous Experiences Guide to British Columbia Immerse yourself in the living Traditions Indigenous travel experiences have the power to move you. To help you feel connected to something bigger than yourself. To leave you changed forever, through cultural exploration and learning. Let your true nature run free and be forever transformed by the stories and songs from the world’s most diverse assembly of living Indigenous cultures. #IndigenousBC | IndigenousBC.com Places To Go CARIBOO CHILCOTIN COAST KOOTENAY ROCKIES NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA TRADITIONAL LANGUAGES: TRADITIONAL LANGUAGES: TRADITIONAL LANGUAGES: TŜILHQOT’IN | TSE’KHENE | DANE-ZAA | ST̓ÁT̓IMCETS KTUNAXA | SECWEPEMCSTIN | NSYILXCƏN SM̓ALGYA̱X | NISG̱A’A | GITSENIMX̱ | DALKEH | WITSUWIT’EN SECWEPEMCSTIN | NŁEʔKEPMXCÍN | NSYILXCƏN | NUXALK NEDUT’EN | DANEZĀGÉ’ | TĀŁTĀN | DENE K’E | X̱AAYDA KIL The Ktunaxa have inhabited the rugged area around X̱AAD KIL The fjordic coast town of Bella Coola, where the Pacific the Kootenay and Columbia Rivers on the west side of Ocean meets mighty rainforests and unmatched Canada’s Rockies for more than 10 000 years. Visitors Many distinct Indigenous people, including the Nisga’a, wildlife viewing opportunities, is home to the Nuxalk to the snowy mountains of Creston and Cranbrook Haida and the Tahltan, occupy the unique landscapes of people and the region’s easternmost point. The continue to seek the adventure this dramatic landscape Northern BC. Indigenous people co-manage and protect Cariboo Chilcotin Coast spans the lower middle of offers. Experience traditional rejuvenation: soak in hot this untamed expanse–more than half of the size of the BC and continues toward mountainous Tsilhqot’in mineral waters, view Bighorn Sheep, and traverse five province–with a world-class system of parks and reserves Territory, where wild horses run. -

Francophone Historical Context Framework PDF

Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Canot du nord on the Fraser River. (www.dchp.ca); Fort Victoria c.1860. (City of Victoria); Fort St. James National Historic Site. (pc.gc.ca); Troupe de danse traditionnelle Les Cornouillers. (www. ffcb.ca) September 2019 Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Table of Contents Historical Context Thematic Framework . 3 Theme 1: Early Francophone Presence in British Columbia 7 Theme 2: Francophone Communities in B.C. 14 Theme 3: Contributing to B.C.’s Economy . 21 Theme 4: Francophones and Governance in B.C. 29 Theme 5: Francophone History, Language and Community 36 Theme 6: Embracing Francophone Culture . 43 In Closing . 49 Sources . 50 2 Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework - cb.com) - Simon Fraser et ses Voya ses et Fraser Simon (tourisme geurs. Historical contexts: Francophone Historic Places • Identify and explain the major themes, factors and processes Historical Context Thematic Framework that have influenced the history of an area, community or Introduction culture British Columbia is home to the fourth largest Francophone community • Provide a framework to in Canada, with approximately 70,000 Francophones with French as investigate and identify historic their first language. This includes places of origin such as France, places Québec, many African countries, Belgium, Switzerland, and many others, along with 300,000 Francophiles for whom French is not their 1 first language. The Francophone community of B.C. is culturally diverse and is more or less evenly spread across the province. Both Francophone and French immersion school programs are extremely popular, yet another indicator of the vitality of the language and culture on the Canadian 2 West Coast. -

Scaling Memory: Reparation Displacement and the Case of BC

Scaling Memory: Reparation Displacement and the Case of BC MATT JAMES University of Victoria In British Columbia, people tend to view history as something that happened last weekend.... Happily, it doesn’t matter here who your ancestors were or who did what to whom 300 years ago. Lisa Hobbs Birnie ~1996! Racist injustices have played a central role in shaping British Columbia; it could hardly be otherwise in a white-dominated settler society built on an ongoing history of Indigenous dispossession and 75 initial years of official racism against Asians. Yet despite the spread of an “age of apol- ogy” ~Gibney et al., 2008!, characterized in many locales by a growing introspection over patterns of historic injustice, considerations of repara- tion still seem marginal in BC, an anomaly to which this article responds. Charting the contours of an amnesiac culture of memory, the follow- ing pages argue that BC’s aloofness from the age of apology reflects a phenomenon I call “reparation displacement.” While some recalcitrant communities resist calls to repair injustice by denying responsibility or claiming no injustice has occurred, reparation displacement works more subtly, redirecting understandings of responsibility instead. In the BC case, reparation displacement is intertwined with the politics of federalism; issues of racist injustice in BC have been conceived almost exclusively— not only by officials but often by redress activists themselves—as mat- ters of federal rather than provincial shame. While more informed debates about Canadian belonging have followed federal apologies for wrongs inflicted on various groups, including Japanese Canadians, Chinese Cana- dians and Indigenous peoples ~James, 2006: 243–45!, BC is a different Acknowledgments: The author would like to thank Caroline Andrew, Alan Cairns, Avigail Eisenberg, Steve Dupré, Chris Kukucha, Daniel Woods, and the two CJPS reviewers for helpful comments on earlier drafts. -

KR/KL Burbot Conservation Strategy

January 2005 Citation: KVRI Burbot Committee. 2005. Kootenai River/Kootenay Lake Conservation Strategy. Prepared by the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho with assistance from S. P. Cramer and Associates. 77 pp. plus appendices. Conservation strategies delineate reasonable actions that are believed necessary to protect, rehabilitate, and maintain species and populations that have been recognized as imperiled, but not federally listed as threatened or endangered under the US Endangered Species Act. This Strategy resulted from cooperative efforts of U.S. and Canadian Federal, Provincial, and State agencies, Native American Tribes, First Nations, local Elected Officials, Congressional and Governor’s staff, and other important resource stakeholders, including members of the Kootenai Valley Resource Initiative. This Conservation Strategy does not necessarily represent the views or the official positions or approval of all individuals or agencies involved with its formulation. This Conservation Strategy is subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of conservation tasks. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Kootenai Tribe of Idaho would like to thank the Kootenai Valley Resource Initiative (KVRI) and the KVRI Burbot Committee for their contributions to this Burbot Conservation Strategy. The Tribe also thanks the Boundary County Historical Society and the residents of Boundary County for providing local historical information provided in Appendix 2. The Tribe also thanks Ray Beamesderfer and Paul Anders of S.P. Cramer and Associates for their assistance in preparing this document. Funding was provided by the Bonneville Power Administration through the Northwest Power and Conservation Council’s Fish and Wildlife Program, and by the Idaho Congressional Delegation through a congressional appropriation administered to the Kootenai Tribe by the Department of Interior. -

Indigenous People of Western New York

FACT SHEET / FEBRUARY 2018 Indigenous People of Western New York Kristin Szczepaniec Territorial Acknowledgement In keeping with regional protocol, I would like to start by acknowledging the traditional territory of the Haudenosaunee and by honoring the sovereignty of the Six Nations–the Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca and Tuscarora–and their land where we are situated and where the majority of this work took place. In this acknowledgement, we hope to demonstrate respect for the treaties that were made on these territories and remorse for the harms and mistakes of the far and recent past; and we pledge to work toward partnership with a spirit of reconciliation and collaboration. Introduction This fact sheet summarizes some of the available history of Indigenous people of North America date their history on the land as “since Indigenous people in what is time immemorial”; some archeologists say that a 12,000 year-old history on now known as Western New this continent is a close estimate.1 Today, the U.S. federal government York and provides information recognizes over 567 American Indian and Alaskan Native tribes and villages on the contemporary state of with 6.7 million people who identify as American Indian or Alaskan, alone Haudenosaunee communities. or combined.2 Intended to shed light on an often overlooked history, it The land that is now known as New York State has a rich history of First includes demographic, Nations people, many of whom continue to influence and play key roles in economic, and health data on shaping the region. This fact sheet offers information about Native people in Indigenous people in Western Western New York from the far and recent past through 2018. -

Aboriginal Title and Private Property John Borrows

The Supreme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference Volume 71 (2015) Article 5 Aboriginal Title and Private Property John Borrows Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/sclr This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Citation Information Borrows, John. "Aboriginal Title and Private Property." The Supreme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference 71. (2015). http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/sclr/vol71/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The uS preme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference by an authorized editor of Osgoode Digital Commons. Aboriginal Title and Private Property John Borrows* Q: What did Indigenous Peoples call this land before Europeans arrived? A: “OURS.”1 I. INTRODUCTION In the ground-breaking case of Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia2 the Supreme Court of Canada recognized and affirmed Aboriginal title under section 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982.3 It held that the Tsilhqot’in Nation possess constitutionally protected rights to certain lands in central British Columbia.4 In drawing this conclusion the Tsilhqot’in secured a declaration of “ownership rights similar to those associated with fee simple, including: the right to decide how the land will be used; the right of enjoyment and occupancy of the land; the right to possess the land; the right to the economic benefits of the land; and the right to pro-actively use and manage the land”.5 These are wide-ranging rights. -

Annual Demographic Estimates: Canada, Provinces and Territories (Total Population Only) 2018

Catalogue no. 91-215-X ISSN 1911-2408 Annual Demographic Estimates: Canada, Provinces and Territories (Total Population only) 2018 Release date: September 27, 2018 How to obtain more information For information about this product or the wide range of services and data available from Statistics Canada, visit our website, www.statcan.gc.ca. You can also contact us by email at [email protected] telephone, from Monday to Friday, 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., at the following numbers: • Statistical Information Service 1-800-263-1136 • National telecommunications device for the hearing impaired 1-800-363-7629 • Fax line 1-514-283-9350 Depository Services Program • Inquiries line 1-800-635-7943 • Fax line 1-800-565-7757 Standards of service to the public Note of appreciation Statistics Canada is committed to serving its clients in a prompt, Canada owes the success of its statistical system to a reliable and courteous manner. To this end, Statistics Canada has long-standing partnership between Statistics Canada, the developed standards of service that its employees observe. To citizens of Canada, its businesses, governments and other obtain a copy of these service standards, please contact Statistics institutions. Accurate and timely statistical information could not Canada toll-free at 1-800-263-1136. The service standards are be produced without their continued co-operation and goodwill. also published on www.statcan.gc.ca under “Contact us” > “Standards of service to the public.” Published by authority of the Minister responsible for Statistics Canada © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada as represented by the Minister of Industry, 2018 All rights reserved. -

British Columbia 1858

Legislative Library of British Columbia Background Paper 2007: 02 / May 2007 British Columbia 1858 Nearly 150 years ago, the land that would become the province of British Columbia was transformed. The year – 1858 – saw the creation of a new colony and the sparking of a gold rush that dramatically increased the local population. Some of the future province’s most famous and notorious early citizens arrived during that year. As historian Jean Barman wrote: in 1858, “the status quo was irrevocably shattered.” Prepared by Emily Yearwood-Lee Reference Librarian Legislative Library of British Columbia LEGISLATIVE LIBRARY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA BACKGROUND PAPERS AND BRIEFS ABOUT THE PAPERS Staff of the Legislative Library prepare background papers and briefs on aspects of provincial history and public policy. All papers can be viewed on the library’s website at http://www.llbc.leg.bc.ca/ SOURCES All sources cited in the papers are part of the library collection or available on the Internet. The Legislative Library’s collection includes an estimated 300,000 print items, including a large number of BC government documents dating from colonial times to the present. The library also downloads current online BC government documents to its catalogue. DISCLAIMER The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily represent the views of the Legislative Library or the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia. While great care is taken to ensure these papers are accurate and balanced, the Legislative Library is not responsible for errors or omissions. Papers are written using information publicly available at the time of production and the Library cannot take responsibility for the absolute accuracy of those sources. -

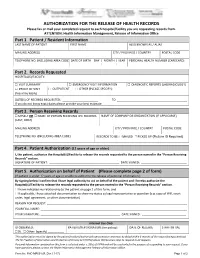

AUTHORIZATION for the RELEASE of HEALTH RECORDS Please Fax Or Mail Your Completed Request to Each Hospital/Facility You Are Requesting Records From

AUTHORIZATION FOR THE RELEASE OF HEALTH RECORDS Please fax or mail your completed request to each hospital/facility you are requesting records from. ATTENTION: Health Information Management, Release of Information Office Part 1. Patient / Resident Information LAST NAME OF PATIENT FIRST NAME ALSO KNOWN AS / ALIAS MAILING ADDRESS CITY / PROVINCE / COUNTRY POSTAL CODE TELEPHONE NO. (INCLUDING AREA CODE) DATE OF BIRTH DAY | MONTH | YEAR PERSONAL HEALTH NUMBER (CARECARD) | | Part 2. Records Requested HOSPITAL(S)/FACILITY: □ VISIT SUMMARY □ EMERGENCY VISIT INFORMATION □ DIAGNOSTIC REPORTS (LAB/RADIOLOGY) □ PROOF OF VISIT □ OUTPATIENT □ OTHER (PLEASE SPECIFY): (fees may apply) DATE(S) OF RECORDS REQUESTED: ______________________ TO ___________________________________________ If you do not know exact dates please provide your best estimate Part 3. Person Receiving Records □ MYSELF OR □ NAME OF PERSON RECEIVING THE RECORDS NAME OF COMPANY OR ORGANIZATION (IF APPLICABLE) (LAST, FIRST) MAILING ADDRESS CITY / PROVINCE / COUNTRY POSTAL CODE TELEPHONE NO. (INCLUDING AREA CODE) RECORDS TO BE: □ MAILED □ PICKED UP (Picture ID Required) Part 4. Patient Authorization (12 years of age or older) I, the patient, authorize the Hospital(s)/Facility to release the records requested to the person named in the “Person Receiving Records” section. SIGNATURE OF PATIENT: ___________________________________________ DATE SIGNED: ____________________________ Part 5. Authorization on behalf of Patient (Please complete page 2 of form) (If patient is under 12 years of age or unable to authorize the release of personal information.) By signing below I confirm that I have legal authority to act on behalf of the patient and I hereby authorize the Hospital(s)/Facility to release the records requested to the person named in the “Person Receiving Records” section.