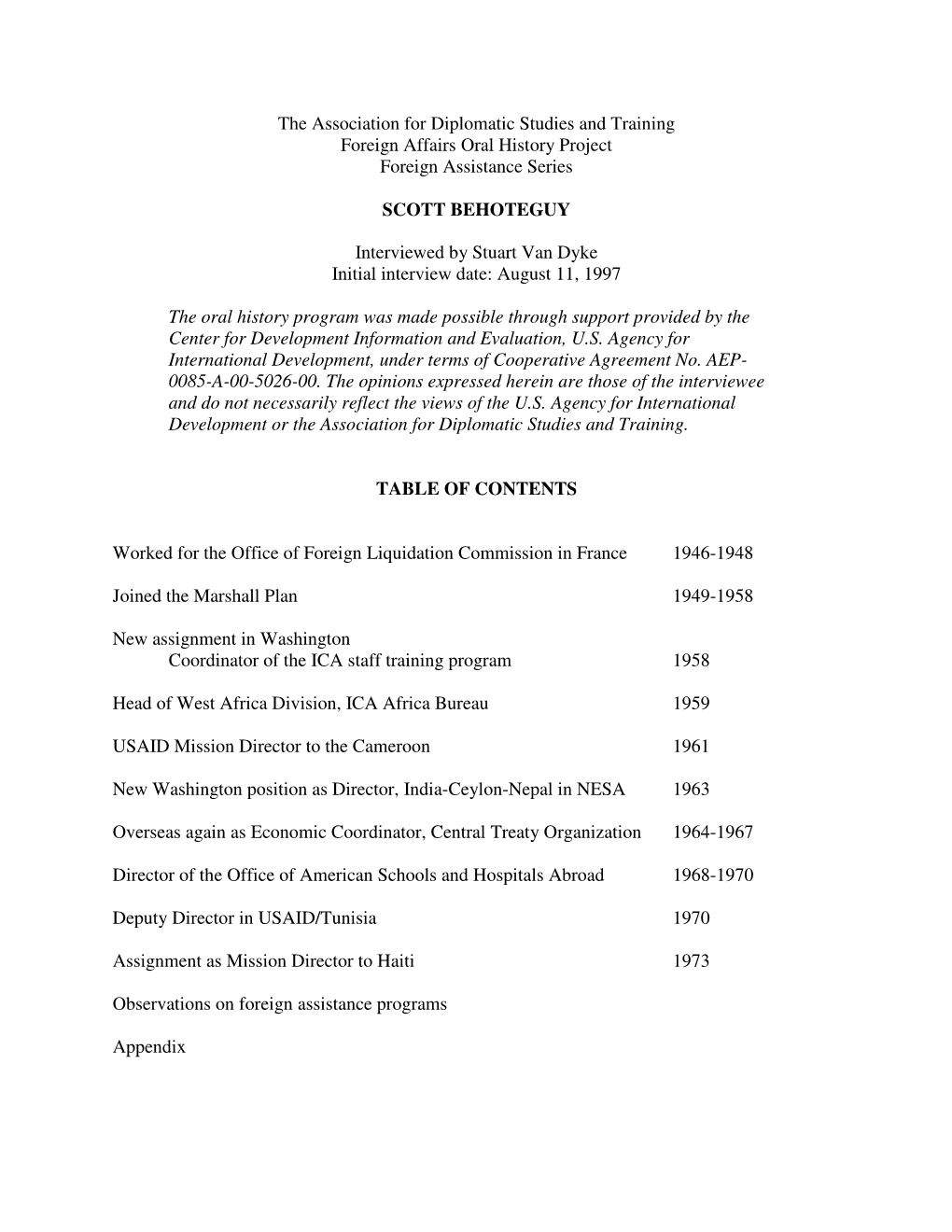

Behoteguy, Scott

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2010 Annual Report WELCOME to CHRISTODORA Katherine F

nature • learning • leadership One East 53rd Street, 14th Floor nature • learning • leadership NewYork, NY 10022 p 212.371.5225 f 212.371.2111 www.christodora.org 2010 annual report WELCOME TO CHRISTODORA Katherine F. C. Cary hristodora and its Nature Learning Leadership programs celebrated another banner year in 2010. We continue to make organizational Cstrides, even as we navigate turbulent economic times. Christodora works directly in the NewYork public school system, oversees after-school programs, leads wilderness environmental education programs over weekends and runs extended summer residential camping programs. Our year-around programs currently reach over 2,500 low-income NewYork City students. Some highlights: • New summer session. Christodora has launched a new summer session: Session V or the “BRIDGE program” Directed towards our most advanced students, participants plan and lead their own seven night wilderness hiking expedition accompanied by seasoned instructors certified inleadership WHAT CHRISTODORA MEANS TO ME development and wilderness education.The session is geared towards the student who may pursue collegiate studies in outdoor environmental studies, an area currently underserved by minorities.The Pierre andTana “Being able to go outside and explore was Matisse Foundation generously underwrote this new initiative. the beginning of me as a person being able • High alumni participation. Over the past few years, former alumni comprise over 50% of the staff at our summer wilderness camp programs. Coming to do the same in life. My idea of how from the same community as our students, our alumni become powerful role models. humans interact on this planet comes • Significant capital improvements. In 2010, with the support of the Hyde and Watson Foundation, we finished a two-year project to rebuild and organize from how I developed at Manice. -

A Historical Perspective of the Permeable IRS Prohibition on Campaigning by Churches Patrick L

Boston College Law Review Volume 42 Issue 4 The Conflicted First Amendment: Tax Article 1 Exemptions, Religious Groups, And Political Activity 7-1-2001 More Honored in the Breach: A Historical Perspective of the Permeable IRS Prohibition on Campaigning by Churches Patrick L. O'Daniel Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the Religion Law Commons, and the Tax Law Commons Recommended Citation Patrick L. O'Daniel, More Honored in the Breach: A Historical Perspective of the Permeable IRS Prohibition on Campaigning by Churches, 42 B.C.L. Rev. 733 (2001), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol42/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MORE HONORED IN THE BREACH: A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE OF THE PERMEABLE IRS PROHIBITION ON CAMPAIGNING BY CHURCHES PATRICK L. O'DANIEL* Abstract: Since 1954, there has been a prohibition on certain forms of intervention in political campaigns by entities exempt frOm taxation under section 501(c) (3) of the Internal Revenue Code—including most. churches. This Article provides a historical perspective on the genesis of this prohibition—the 1954 U.S. Senate campaign of its sponsor, Lyndon Baines Johnson, and the involvement of religious entities and other 501 (c) (3) organizations in his political campaign. Although Johnson was not opposed to using churches to advance his own political interests, lie (lid seek to prevent ideological, tax-exempt organizations from funding McCarthyite candidates including his opponent in the Democratic primary, Dudley Dougherty. -

Marine Cultural and Historic Newsletter Monthly Compilation of Maritime Heritage News and Information from Around the World Volume 2.2, 2005 (February)1

Marine Cultural and Historic Newsletter Monthly compilation of maritime heritage news and information from around the world Volume 2.2, 2005 (February)1 his newsletter is provided as a service by the All material contained within the newsletter is excerpted National Marine Protected Areas Center to share from the original source and is reprinted strictly for T information about marine cultural heritage and information purposes. The copyright holder or the historic resources from around the world. We also hope contributor retains ownership of the work. The to promote collaboration among individuals and Department of Commerce’s National Oceanic and agencies for the preservation of cultural and historic Atmospheric Administration does not necessarily resources for future generations. endorse or promote the views or facts presented on these sites. The information included here has been compiled from Newsletters are now available in Cultural and many different sources, including on-line news sources, the federal agency personnel and web sites, and from Historic Resources section of the MPA.gov web site. To cultural resource management and education receive the newsletter, send a message to professionals. [email protected] with “subscribe MCH newsletter” in the subject field. Similarly, to remove yourself from the list, send the subject “unsubscribe We have attempted to verify web addresses, but make MCH newsletter”. Feel free to provide as much contact no guarantee of accuracy. The links contained in each information as you would like in the body of the newsletter have been verified on the date of issue. message so that we may update our records. Federal Agencies National Park Service (Department of the Interior) (courtesy of Erika Martin Seibert, National Register of Historic Places) From the very beginning, this nation has been tied to its oceans, lakes, and rivers. -

Newjersey and President

Fall/Winter | 2016 ConservationNew Jersey Just as a picture is worth a thousand words, maps tell the story of why a parcular piece of land should be protected forever. SEE STORY PAGE 4 Big Heart of the Pine Barrens: 12 The Franklin Parker Preserve expands to 11,379 acres. Save the Habitat: 14 Endangered animals spotted along the route of a proposed natural gas pipeline. 99-year-old Map Preserved: 16 Historical geology maps of Central and Northern New Jersey donated for preservation. Trustees Kenneth H. Klipstein, II HONORARY TRUSTEES PRESIDENT Hon. Brendan T. Byrne Wendy Mager Catherine M. Cavanaugh FIRST VICE PRESIDENT Hon. James J. Florio Hon. Thomas H. Kean Catherine Bacon Winslow SECOND VICE PRESIDENT Hon. Christine Todd Whitman From Our Robert J. Wolfe Executive Director TREASURER ADVISORY COUNCIL Edward F. Babbott Michele S. Byers Pamela P. Hirsch Nancy H. Becker SECRETARY C. Austin Buck Penelope Ayers Bradley M. Campbell ASSISTANT SECRETARY Christopher J. Daggett John D. Hatch Mapping a course for land preservation H. R. Hegener Cecilia Xie Birge Hon. Rush D. Holt Roger Byrom Susan L. Hullin If a picture’s worth a thousand words, a good map using today’s technology is Theodore Chase, Jr. Cynthia K. Kellogg Jack R. Cimprich worth a million words! Maps are essential tools and are used every day in the work Blair MacInnes Rosina B. Dixon, M.D. Thomas J. Maher of preserving land. Clement L. Fiori Scott McVay Chad Goerner David F. Moore Neil Grossman Mary W. T. Moore Maps help identify properties that connect existing preserved lands. -

Chaliapin to Get Georgel

Edwin D. Morgan's PERSONAL INTELLIGENCE. Exhibitiort Golf f Mrs. Charles Scribner, Jr., and 'Dime Novel*) Chaliapin to Get GeorgeL. Thompsonj DIED. NEW YORK. CHITTENDEN..Entered Into rent at Cran- Miss Elizabeth will return to on brook, Guilford, Conn,, on Friday, Sep¬ Son Is Engaged Billings Tailer Links $2,500 Each Night Wealthy, Retired tember 13. Simeon Baldwin Chittenden, New York from Woodstock, Vt , on son of the late .Sure n Baldwin and Mary September 20. Haitwell Chittenden and lovtrig husbano to Miss Caswell Attracts at /s Dead of Man lllll Chittenden, aged 77 year*. Major-Gen. Charles F. Roe and hi.« Society Metropolitan Banker, Notice of funeral hereafter. daughter, Mrs. Prescott Slade, are at COOKER.William K CAMPBELL WV Highland Falls. Once Was N'KitAS. CHI'RCH, Broadway, 66th »t. Marriage to Link Oldest Two Hundred Sec Miss Collett Russian Basso to K<|iinl Ca-j Philadelphia Man Saturday. 10 A. M Mrs. Patrick A. Valentine, who was of C< ItBUT At Elizabeth. N. J September 13, New York and Boston at Southampton this summer, arrived Defeat Miss Gordon.Other ruso'g Fpp, but dross Earn¬ Husband Well Known 1922. William .1. Corbet, aged A3 year* at the Plaza Func ral service* a' his late home, 31 Families. yesterday. Events. .1 iilie Scotland road, ic 2 :.K> Monday afternoon Newport ings AVil 1 Bo Loss. Phillips. .September Is. Interment at COftvenkHK't Mr. Amos Tuck French. Jr.. returned of family , Ev srgreen Cemetery. yesterday from Newport to the Van- DK VINNil 'in will Friday morning, Septem¬ Special Dispatch to Tub New York Hbrai.d. -

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES BRICKER, Mr

1951 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE 4795 The PRESIDING OFFICER <Mr. The Senator from Indiana [Mr. CAPE Esther E.. Lenox, WAC, Ll010270. ELLENDER in the chair) . A quorum is HART] is absent by leave of the Senate. Sonja G. Lunoe, WAC, Ll010241. not . present. The clerk will call the If present, he would vote "nay." Kitt M. MacMichael, WAC, Ll010245 . names of the absent Senators. The Senator from · Vermont [Mr. Phyllis J. Morsman, WAC, Ll010259. Patricia J. Pomeroy, WAC, Ll010272. The Chief Clerk called the names of FLANDERS], the Senator from Indiana Dorothy Slierba, WAC, Ll010275. the absent Senators; and Mr. ANDERSON, [Mr. JENNER], and the Senator from New Jacquelyn R. Sollars, WAC, Ll010257. Mr. HICKENLOOPER, Mr. JOHNSTON of Hampshire [Mr. TOBEY] are detained on Barbara J. Wardell, WAC, Ll010282. South Carolina, 1\::.-. MOODY, Mr. MUR official business. Helen A. Way, WAC, Ll010280. RAY, Mr. PASTORE and Mr. WILLIAMS an The result was announced-yeas 42, Martha L. Weeks, WAC, L1010269. swered to their names when called. nays 39, as follows: Elizabeth A. Whitaker, WAC, Ll010281. The PRESIDING OFFICER. A quo- Kathleen I. Wilkes, WAC, Ll010234. YEA8-42 Sadie E. Yoshizaki, WAC, Ll010236. rum is not present. · Anderson Hoey Maybank Mr. McFARLAND: I move that the Benton Holland Monroney IN THE NAVY Sergeant at Arms be directed to request Byrd Humphrey Moody . Rear Adm. Robert M. Griffin, :United States Clements Johnson, Colo. Murray Navy, when retired, to be placed on the re the attendance of absent Senators. Connally The motion was agreed to. Johnson, Tex. Neely tired list with the rank of vice admiral. -

Summer-Fall 1982

INANEWSLETTER Summer/Fall 1982 INA FIELD SEASON-1982 Surveying in Turkey, analyzing in the Turks and Caicos, excavating in Jamaica. In this issue we provide INA members Underwater Archaeology a two-week sum tinuing conservation of wooden hull, glass with an overview of the work carried out by mer school initiated by the Council of cargo, and iron implements from the Glass the Institute on various sites and projects Europe's leading nautical archaeologists. Wreck. in 1982. Many of these activities (notably Bodrum was chosen because of the Muse Bodrum also was chosen for the sum the Council of Europe Field School and the um's unique displays, including the re mer school because INA's excavation of a Molasses Reef Excavation) will be the mains of Bronze Age shipwrecks ex 16th-century wreck at Yassi Ada is less subject of major articles in forthcoming cavated at Cape Gelidonya and Sheytan than two hours distant by car and boat, issues. Deresi, seventh- and fourth-century A.D. and the excavation gave participants the YASSI ADA/BODRUM Byzantine wrecks at Yassi Ada, and the opportunity to dive on the site and ex eleventh-century "Glass Wreck" at Serce change ideas with INA and Bodrum Mu In Turkey, INA remained active on a Liman. The museum further provided the seum staffs. Attending were representa number of fronts in 1982. In July it co setting in which participants observed tives of France, England, Italy, Spain, hosted with the Bodrum Museum of techniques used by INA staff in the con- Tunisia, Poland, Turkey, Belgium, Holland, Switzerland, and the United States. -

Montana Kaimin, February 2, 1965 Associated Students of Montana State University

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Associated Students of the University of Montana Montana Kaimin, 1898-present (ASUM) 2-2-1965 Montana Kaimin, February 2, 1965 Associated Students of Montana State University Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper Recommended Citation Associated Students of Montana State University, "Montana Kaimin, February 2, 1965" (1965). Montana Kaimin, 1898-present. 4123. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper/4123 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Associated Students of the University of Montana (ASUM) at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Montana Kaimin, 1898-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Solon Hails Churchill as 'Great’ or take into account its lessons By TOBY LAWRENCE The Germans were right outside “I borrowed a Liberator bomber a series of meeting to discuss the from the 8th Air Force and we opening of a second front to take are destined to relive it. I’m afraid Kaimin Reporter the gates of Cairo.” Sen. Gerald recalled when Mr. went to Tehran and then on to pressure off the Russian Army. we as Americans are prone to for HELENA—The minority leader Churchill announced he was going Moscow. We were met by Mr. “It was the first time the Western get history,” he said. of the Montana Senate, who to Moscow. Gen. Maxwell told Mr. Molotov and members of the Rus leaders had met with the Rus Picking out an incident, the sen knew Sir Winston Churchill dur Gerard to get a plane and they sian hierarchy,” Sen. -

A Historical Perspective of the Permeable IRS Prohibition on Campaigning by Churches Patrick L

Boston College Law Review Volume 42 Issue 4 The Conflicted First Amendment: Tax Article 1 Exemptions, Religious Groups, And Political Activity 7-1-2001 More Honored in the Breach: A Historical Perspective of the Permeable IRS Prohibition on Campaigning by Churches Patrick L. O'Daniel Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the Religion Law Commons, and the Tax Law Commons Recommended Citation Patrick L. O'Daniel, More Honored in the Breach: A Historical Perspective of the Permeable IRS Prohibition on Campaigning by Churches, 42 B.C.L. Rev. 733 (2001), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol42/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MORE HONORED IN THE BREACH: A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE OF THE PERMEABLE IRS PROHIBITION ON CAMPAIGNING BY CHURCHES PATRICK L. O'DANIEL* Abstract: Since 1954, there has been a prohibition on certain forms of intervention in political campaigns by entities exempt frOm taxation under section 501(c) (3) of the Internal Revenue Code—including most. churches. This Article provides a historical perspective on the genesis of this prohibition—the 1954 U.S. Senate campaign of its sponsor, Lyndon Baines Johnson, and the involvement of religious entities and other 501 (c) (3) organizations in his political campaign. Although Johnson was not opposed to using churches to advance his own political interests, lie (lid seek to prevent ideological, tax-exempt organizations from funding McCarthyite candidates including his opponent in the Democratic primary, Dudley Dougherty. -

Winter 1984 INA's 1983 SEASON

Winter 1984 INA'S 1983 SEASON L to R: Ottoman Wreck hull remains; glass mending in Bodrum; sediment coring at Sf. Ann's Bay; fish basket in Port Royal. In this issue, individual project directors Under the direction of Cemal Pulak, a tion of iron objects, including anchors. It and research personnel provide INA mem Texas A&M University nautical archaeolo would now appear that at least half the bers with an overview of the work carried gy graduate student, four local menders eight anchors on board had been broken out by the Institute on various projects in are tending the arduous task of piecing and hastily repaired-little wonder medie 1983. Many of these activities will be the together thousands of fragments of broken val ships carried so many spares. Joseph subject of major articles in forthcoming glass to form complete or near complete Schwarzer has begun the difficult task of issues. vessels. Each month brings new excite replicating a large assemblage of objects ment as George Bass opens the envelope within a wicker basket, an assemblage that THE GLASS WRECK containing Sema Pulak's drawings of the includes a bronze steelyard with iron chain latest reconstructed glass vessels. Some and balance pan, a padlock, a dozen Although the Glass Wreck excavation months the envelope contains drawings of chisels and drills, a wood rasp, a claw was completed in 1979, the mending of the entirely new vessel types, adding to what hammer, and spare nails. In the same thousands of broken glass vessels, the is already the largest collection of medie envelope with the glass drawings, Netia conservation and reconstruction of the hull val Islamic glass in existence. -

The Sidney Herald—Wednesday, February 24, 19S0 V S « ?

m ' 1 iiN* ill.. ,^!?r ' H Kl i 8—The Sidney Herald—Wednesday, February 24, 19S0 v s « ?.. J / REPUBLICAN SUMNER GERARD JO NOMINEE FOR U. S. SENATE COME IIV AM» HELP ES CELEBRATE »ER Rep. Sumner Gerard, 43-year I the Advisory Committee of the old Ennis cattleman, today filed Montana State University School * formally for the Republican U.S. of Business Administration. He ü 8TH Senate nomination. bas had extensive governmental The World War II veteran and experience on both state and na- IT m three term Madison County leg- tional levels. - islator became the first Republican The Senate candidate is a mem- nominee for the position now held ber of the Masons, Elks, VFW, v \ by 83-year-old Democrat James E. U.S. Marine Corps. Reserve, Mon- . Murray. tana Stockgrowers Association, £ Gerard said, “An effective U.S. Montana Reclamation Association, (7 v ■ f: w I: < Senator from Montana must work Montana Peace Officers Associa- ; 1 ■ first for things’ which will build tion, American Society of Ranch ; i :: W Montana. My platform includes Management, Montana Farm Bur eau Federation, Civil Air Patrol, III ■ * x;: ►< r :: 'S I / V? and Aircraft Owners and Pilots i ft Association. :? :> [* : j I 5 0k s I I 0 Proclamation $ % t ■:y i ■ Mayor Harold Mercer today signed a proclamation designating BI y&i Sunday, February 28, as Heart if Sunday in Sidney. )1 WHEREAS the nation’s most Q) t ^ J *** distinguished cardiologists have as IÎ7V ^ I r sured the public that medical re search holds the key to the control "tÜlÿiii I i.j and eventual conquest of the heart and blood vessel diseases; % WHEREAS the American Heart l.\ OER NEW IIIILUIM. -

Silver Squelchers Twenty Five & Their Interesting Associates

Silver Squelchers Twenty Five & Their Interesting Associates Members Involved With Investment Companies Part Two Suggested Theme Music for The Pilgrims Society! “He spoke openly against the Society” (Line from “The Rifleman,” March 3, 1963) Presented August 2015 by Charles Savoie “The Order will thus work silently, and securely; and though the generous benefactors of the human race are thus deprived of the applause of the world, they have the noble pleasure of seeing their work prosper in their hands. Out secret association works in a way that nothing can withstand, and mankind shall soon be free and happy.” ---attributed to Austrian professor Adam Weishaupt, credited with founding the Order of Illuminati circa 1776. The British Empire, since renamed a “commonwealth,” is easily the most globalist entity to ever exist. The Illuminati concepts fit in perfectly, and the British Royal house and its surrounding nobility are connected by ancestry and marriage to Royal houses all over Europe and to the major and mid-tier global banking dynasties. 1) James W. Gerard 5th (1961---; Pilgrims Society as of undetermined) has a fantastic genealogy and is senior adviser to North Sea Partners, a specialty financial house. He’s on the board of advisers to the Elliott School of International Affairs of George Washington University in the District of Columbia. This is ironic inasmuch as George Washington in his farewell Presidential address in 1796 warned the country against “the insidious wiles of foreign influence,” and this matter of The Pilgrims New York being the correspondent outpost here for London financiers and British royalty! Other members of the board of the Elliott School include officials of Bank of America, Albright Stonebridge Group (discussed in Silver Squelchers #14) and the chairman of Global Gold Corporation (Van Krikorian), New York Times and other typical globalist organizations.