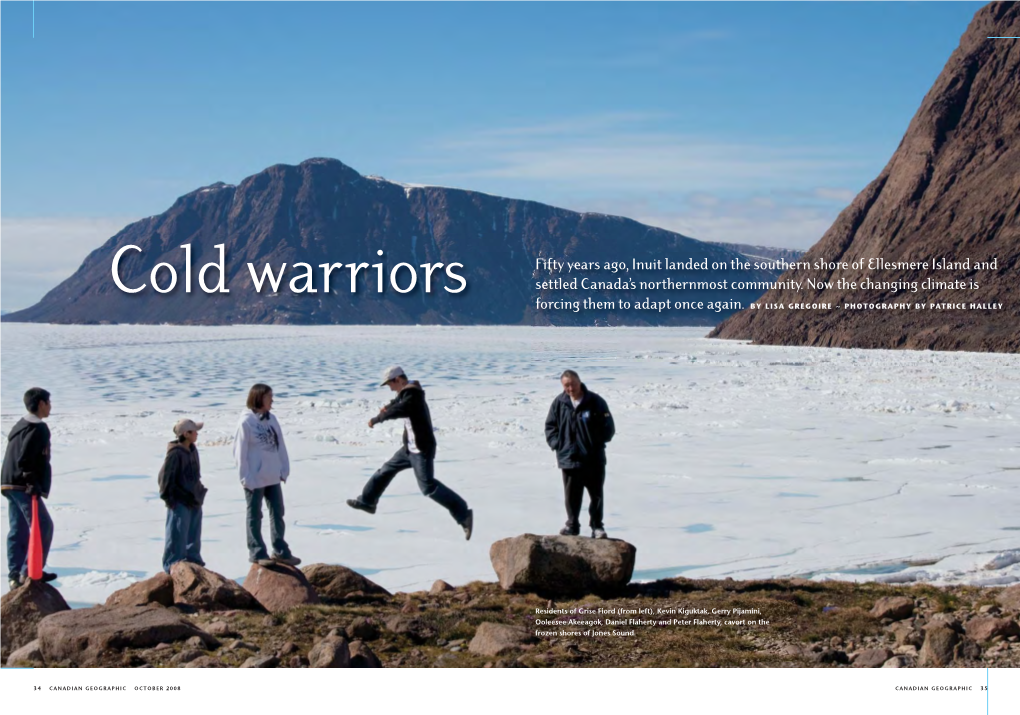

Cold Warriors Settled Canada’S Northernmost Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

15 Canadian High Arctic-North Greenland

15/18: LME FACTSHEET SERIES CANADIAN HIGH ARCTIC-NORTH GREENLAND LME tic LMEs Arc CANADIAN HIGH ARCTIC-NORTH GREENLAND LME MAP 18 of Central Map Arctic Ocean LME North Pole Ellesmere Island Iceland Greenland 15 "1 ARCTIC LMEs Large ! Marine Ecosystems (LMEs) are defined as regions of work of the ArcNc Council in developing and promoNng the ocean space of 200,000 km² or greater, that encompass Ecosystem Approach to management of the ArcNc marine coastal areas from river basins and estuaries to the outer environment. margins of a conNnental shelf or the seaward extent of a predominant coastal current. LMEs are defined by ecological Joint EA Expert group criteria, including bathymetry, hydrography, producNvity, and PAME established an Ecosystem Approach to Management tropically linked populaNons. PAME developed a map expert group in 2011 with the parNcipaNon of other ArcNc delineaNng 17 ArcNc Large Marine Ecosystems (ArcNc LME's) Council working groups (AMAP, CAFF and SDWG). This joint in the marine waters of the ArcNc and adjacent seas in 2006. Ecosystem Approach Expert Group (EA-EG) has developed a In a consultaNve process including agencies of ArcNc Council framework for EA implementaNon where the first step is member states and other ArcNc Council working groups, the idenNficaNon of the ecosystem to be managed. IdenNfying ArcNc LME map was revised in 2012 to include 18 ArcNc the ArcNc LMEs represents this first step. LMEs. This is the current map of ArcNc LMEs used in the This factsheet is one of 18 in a series of the ArcCc LMEs. OVERVIEW: CANADIAN HIGH ARCTIC-NORTH GREENLAND LME The Canadian High Arcc-North Greenland LME (CAA) consists of the northernmost and high arcc part of Canada along with the adjacent part of North Greenland. -

Preliminary Mass-Balance Food Web Model of the Eastern Chukchi Sea

NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-AFSC-262 Preliminary Mass-balance Food Web Model of the Eastern Chukchi Sea by G. A. Whitehouse U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service Alaska Fisheries Science Center December 2013 NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS The National Marine Fisheries Service's Alaska Fisheries Science Center uses the NOAA Technical Memorandum series to issue informal scientific and technical publications when complete formal review and editorial processing are not appropriate or feasible. Documents within this series reflect sound professional work and may be referenced in the formal scientific and technical literature. The NMFS-AFSC Technical Memorandum series of the Alaska Fisheries Science Center continues the NMFS-F/NWC series established in 1970 by the Northwest Fisheries Center. The NMFS-NWFSC series is currently used by the Northwest Fisheries Science Center. This document should be cited as follows: Whitehouse, G. A. 2013. A preliminary mass-balance food web model of the eastern Chukchi Sea. U.S. Dep. Commer., NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-AFSC-262, 162 p. Reference in this document to trade names does not imply endorsement by the National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-AFSC-262 Preliminary Mass-balance Food Web Model of the Eastern Chukchi Sea by G. A. Whitehouse1,2 1Alaska Fisheries Science Center 7600 Sand Point Way N.E. Seattle WA 98115 2Joint Institute for the Study of the Atmosphere and Ocean University of Washington Box 354925 Seattle WA 98195 www.afsc.noaa.gov U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Penny. S. Pritzker, Secretary National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Kathryn D. -

Thermal Physics, Daniel V

PHY293F1 - Particles Part Lecturer: Prof. Kaley Walker Office: MP712; 416 978 8218 E-mail: [email protected] • Replies to e-mail within 2 business days (i.e. excluding weekends) but will not answer detailed questions by e-mail Office hours: Fridays 14:00 – 15:00 Course website for Particles Part: • http://www.physics.utoronto.ca/~phy293h1f/293_particles.html • Class announcements given on the website Lectures: 3 hours/week in MP203 • Mon. 15:00-17:00, Tues. 15:00-17:00 and Fri. 15:00-17:00 My research (1) • I am the Deputy Mission Scientist for the Atmospheric Chemistry Experiment (ACE) satellite • Launched in August 2003 for a two-year mission and still going strong… • We measure over 30 different species in the ACE satellite Earth’s atmosphere each day to study the changing composition relating to – Ozone depletion –Air quality –Climate change My research (2) • Studying the Arctic atmosphere from the Canadian high Arctic - PEARL in Eureka, Nunavut • A team of researchers will be going up there to see what happens when sunlight returns to the high Arctic (Feb.- Apr.) • On Ellesmere Island, 1100 km from the North Pole • PEARL is the most northern civilian research laboratory in the world • Nearest community is 420 km south at Grise Fiord PEARL, Eureka, Nunavut, 80 °N Textbook and Resources An Introduction to Thermal Physics, Daniel V. Schroeder (Addison Wesley Longman, 2000) • Available at UoT bookstore etc., should be some used ones Additional references available on short-term loan from the Physics and Gerstein libraries -

Atlantic Walrus Odobenus Rosmarus Rosmarus

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Atlantic Walrus Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Atlantic walrus Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. ix + 65 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous reports: COSEWIC 2000. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Atlantic walrus Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus (Northwest Atlantic Population and Eastern Arctic Population) in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 23 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Richard, P. 1987. COSEWIC status report on the Atlantic walrus Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus (Northwest Atlantic Population and Eastern Arctic Population) in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-23 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge D.B. Stewart for writing the status report on the Atlantic Walrus Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Andrew Trites, Co-chair, COSEWIC Marine Mammals Species Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la situation du morse de l'Atlantique (Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus) au Canada – Mise à jour. -

Canadian Arctic Tide Measurement Techniques and Results

International Hydrographie Review, Monaco, LXIII (2), July 1986 CANADIAN ARCTIC TIDE MEASUREMENT TECHNIQUES AND RESULTS by B.J. TAIT, S.T. GRANT, D. St.-JACQUES and F. STEPHENSON (*) ABSTRACT About 10 years ago the Canadian Hydrographic Service recognized the need for a planned approach to completing tide and current surveys of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago in order to meet the requirements of marine shipping and construction industries as well as the needs of environmental studies related to resource development. Therefore, a program of tidal surveys was begun which has resulted in a data base of tidal records covering most of the Archipelago. In this paper the problems faced by tidal surveyors and others working in the harsh Arctic environment are described and the variety of equipment and techniques developed for short, medium and long-term deployments are reported. The tidal characteris tics throughout the Archipelago, determined primarily from these surveys, are briefly summarized. It was also recognized that there would be a need for real time tidal data by engineers, surveyors and mariners. Since the existing permanent tide gauges in the Arctic do not have this capability, a project was started in the early 1980’s to develop and construct a new permanent gauging system. The first of these gauges was constructed during the summer of 1985 and is described. INTRODUCTION The Canadian Arctic Archipelago shown in Figure 1 is a large group of islands north of the mainland of Canada bounded on the west by the Beaufort Sea, on the north by the Arctic Ocean and on the east by Davis Strait, Baffin Bay and Greenland and split through the middle by Parry Channel which constitutes most of the famous North West Passage. -

NIRB Uuktuutinga Ihivriuqhikhamut #125333 Windfall Film - Ellesmere Island

NIRB Uuktuutinga Ihivriuqhikhamut #125333 Windfall Film - Ellesmere Island Uuktuutinga Qanurittuq: New Havaap Qanurittunia: Puulaktunik Takuyaktuiyunik Akuiyunik Aihinit Uuktuutinga Ublua: 4/18/2018 10:07:37 PM Period of operation: from 0001-01-01 to 0001-01-01 Piumayaat Angirutinga: from 0001-01-01 to 0001-01-01 Havauhikhaq Ikayuqtinga: Kristyn Thoburn Arctic Kingdom P.O. Box #6117 Iqaluit ON X0A 0H0 Canada Hivayautit Nampanga:: 867-979-1900, Kayumiktukkut Nampanga:: QANURITTUT Tukihiannaqtunik havaariyauyumayumik uqauhiuyun Qablunaatitut: Windfall Films is proposing to spend two weeks, from July 1-15th, 2018, on Ellesmere Island. The primary goal of the project is to film the rocks and fossils of at least two different fossil sites in this location. The team will be comprised of professional researchers and filmmakers, including vertebrate palaeontologist, Jaelyn Eberle (a long-time Canadian Arctic researcher), and paleobotanist Kirk Johnson, as well as six members from Windfall Films. Additionally, an experienced Expedition Leader and Inuit Senior Guide from Arctic Kingdom, based in Iqaluit, NU, will participate on the film expedition. Arctic Kingdom will handle the transportation to and from the field localities, as well as all other logistics, including safety, risk management, guidance and regional knowledge, camping equipment, water and food resources and wildlife monitoring.The early Eocene Epoch (ca. 50 – 55 million years ago) was a period of uniquely warm polar environments. Canada’s Arctic, including Ellesmere Island, was blanketed by rainforests inhabited by alligators, turtles, and a range of mammals including primates and tapirs. This unique biota reflects a greenhouse world, offering a climatic and ecologic deep time analog of a mild ice-free Arctic that may be our best means to predict what is in store for the future Arctic as climate continues to change. -

Polar Continental Shelf Program Science Report 2019: Logistical Support for Leading-Edge Scientific Research in Canada and Its Arctic

Polar Continental Shelf Program SCIENCE REPORT 2019 LOGISTICAL SUPPORT FOR LEADING-EDGE SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH IN CANADA AND ITS ARCTIC Polar Continental Shelf Program SCIENCE REPORT 2019 Logistical support for leading-edge scientific research in Canada and its Arctic Polar Continental Shelf Program Science Report 2019: Logistical support for leading-edge scientific research in Canada and its Arctic Contact information Polar Continental Shelf Program Natural Resources Canada 2464 Sheffield Road Ottawa ON K1B 4E5 Canada Tel.: 613-998-8145 Email: [email protected] Website: pcsp.nrcan.gc.ca Cover photographs: (Top) Ready to start fieldwork on Ward Hunt Island in Quttinirpaaq National Park, Nunavut (Bottom) Heading back to camp after a day of sampling in the Qarlikturvik Valley on Bylot Island, Nunavut Photograph contributors (alphabetically) Dan Anthon, Royal Roads University: page 8 (bottom) Lisa Hodgetts, University of Western Ontario: pages 34 (bottom) and 62 Justine E. Benjamin: pages 28 and 29 Scott Lamoureux, Queen’s University: page 17 Joël Bêty, Université du Québec à Rimouski: page 18 (top and bottom) Janice Lang, DRDC/DND: pages 40 and 41 (top and bottom) Maya Bhatia, University of Alberta: pages 14, 49 and 60 Jason Lau, University of Western Ontario: page 34 (top) Canadian Forces Combat Camera, Department of National Defence: page 13 Cyrielle Laurent, Yukon Research Centre: page 48 Hsin Cynthia Chiang, McGill University: pages 2, 8 (background), 9 (top Tanya Lemieux, Natural Resources Canada: page 9 (bottom -

Qikiqtani Region Arctic Ocean

OVERVIEW 2017 NUNAVUT MINERAL EXPLORATION, MINING & GEOSCIENCE QIKIQTANI REGION ARCTIC OCEAN OCÉAN ARCTIQUE LEGEND Commodity (Number of Properties) Base Metals, Active (2) Mine, Active (1) Diamonds, Active (2) Quttinirpaaq NP Sanikiluaq Mine, Inactive (2) Gold, Active (1) Areas with Surface and/or Subsurface Restrictions 10 CPMA Caribou Protection Measures Apply ISLANDS Belcher MBS Migratory Bird Sanctuary NP National Park Nares Strait Islands NWA National Wildlife Area - ÉLISABETH Nansen TP Territorial Park WP Wildlife Preserve WS Wildlife Sanctuary Sound ELLESMERE ELIZABETHREINE ISLAND Inuit Owned Lands (Fee simple title) Kane Surface Only LA Agassiz Basin Surface and Subsurface Ice Cap QUEEN Geological Mapping Programs Canada-Nunavut Geoscience Office ÎLES DE Kalaallit Nunaat Boundaries Peary Channel Müller GREENLAND/GROENLAND NLCA1 Nunavut Settlement Area Ice CapAXEL Nunavut Regions HEIBERG ÎLE (DENMARK/DANEMARK) NILCA 2 Nunavik Settlement Area ISLAND James Bay WP Provincial / Territorial D'ELLESMERE James Bay Transportation Routes Massey Sound Twin Islands WS Milne Inlet Tote Road / Proposed Rail Line Hassel Sound Prince of Wales Proposed Steensby Inlet Rail Line Prince Ellef Ringnes Icefield Gustaf Adolf Amund Meliadine Road Island Proposed Nunavut to Manitoba Road Sea Ringnes Eureka Sound Akimiski 1 Akimiski I. NLCA The Nunavut Land Claims Agreement Island Island MBS 2 NILCA The Nunavik Inuit Land Claims Agreement Norwegian Bay Baie James Boatswain Bay MBS ISLANDSHazen Strait Belcher Channel Byam Martin Channel Penny S Grise Fiord -

January 19, 2021 Iviq Hunters & Trappers Organization Grise Fiord

January 19, 2021 Iviq Hunters & Trappers Organization Grise Fiord, Nunavut X0A 0J0 email: [email protected] VIA EMAIL Subject: Construction at the Eureka High Arctic Weather Station Notification Request Dear Iviq Hunters & Trappers Organization, Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) proposes to undertake various construction activities at the Eureka High Arctic Weather Station (HAWS) to upgrade existing, construct new, or decommission surplus infrastructure. The HAWS is located on the north side of Slidre Fjord, at the northwestern tip of Fosheim Peninsula, Ellesmere Island, Nunavut. ECCC has retained Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC), and the consulting firm AECOM Canada LTD. to engage with interested groups who may wish to receive project status updates or general information on upcoming project activities. Feedback will help ECCC understand how these activities may impact your community. Feedback may also support ongoing operations and planning efforts of the proposed activities at the HAWS. About the Eureka HAWS Since 1947, ECCC has owned and managed the overall operations and maintenance of HAWS under Land Reserve #1021. The total area of the HAWS main operational site is approximately 2.23 hectares. There are presently 15 primary buildings and other facilities at the HAWS. The Eureka runway is located 1.5 km northeast of the HAWS main site and is the most common way by which the HAWS is accessed year-round. The Eureka HAWS is an operational weather monitoring facility as well as a hub of activity for the Department of National Defence, the Polar Continental Shelf Project, and the Polar Environment Atmospheric Research Lab (PEARL). Proposed Activities The following activities are proposed to be completed between 2021 to 2025: Replacement of new drinking water reservoir and upgrades to existing sewage treatment facility. -

Canada's Arctic Marine Atlas

Lincoln Sea Hall Basin MARINE ATLAS ARCTIC CANADA’S GREENLAND Ellesmere Island Kane Basin Nares Strait N nd ansen Sou s d Axel n Sve Heiberg rdr a up Island l Ch ann North CANADA’S s el I Pea Water ry Ch a h nnel Massey t Sou Baffin e Amund nd ISR Boundary b Ringnes Bay Ellef Norwegian Coburg Island Grise Fiord a Ringnes Bay Island ARCTIC MARINE z Island EEZ Boundary Prince i Borden ARCTIC l Island Gustaf E Adolf Sea Maclea Jones n Str OCEAN n ait Sound ATLANTIC e Mackenzie Pe Ball nn antyn King Island y S e trait e S u trait it Devon Wel ATLAS Stra OCEAN Q Prince l Island Clyde River Queens in Bylot Patrick Hazen Byam gt Channel o Island Martin n Island Ch tr. Channel an Pond Inlet S Bathurst nel Qikiqtarjuaq liam A Island Eclipse ust Lancaster Sound in Cornwallis Sound Hecla Ch Fitzwil Island and an Griper nel ait Bay r Resolute t Melville Barrow Strait Arctic Bay S et P l Island r i Kel l n e c n e n Somerset Pangnirtung EEZ Boundary a R M'Clure Strait h Island e C g Baffin Island Brodeur y e r r n Peninsula t a P I Cumberland n Peel Sound l e Sound Viscount Stefansson t Melville Island Sound Prince Labrador of Wales Igloolik Prince Sea it Island Charles ra Hadley Bay Banks St s Island le a Island W Hall Beach f Beaufort o M'Clintock Gulf of Iqaluit e c n Frobisher Bay i Channel Resolution r Boothia Boothia Sea P Island Sachs Franklin Peninsula Committee Foxe Harbour Strait Bay Melville Peninsula Basin Kimmirut Taloyoak N UNAT Minto Inlet Victoria SIA VUT Makkovik Ulukhaktok Kugaaruk Foxe Island Hopedale Liverpool Amundsen Victoria King -

2011 Canada and the North Cover Photo © Andrew Stewart, 2009

Eagle-Eye Tours Eagle-Eye 4711 Galena St., Windermere, British Columbia, Canada V0B 2L2 Tours 1-800-373-5678 | www.Eagle-Eye.com | [email protected] Travel with Vision 2011 Canada and the North Cover photo © Andrew Stewart, 2009 Dear Adventurers, In 2011, we at Eagle-Eye Tours are delighted to present another series of outstanding voyages. Every single one will not only bring you to places of beauty and importance, but will connect you to them. Through the summer season we have the great thrill of exploring the mighty North Atlantic. We’ll range all the way from the cities of Scotland through the Outer Hebrides, north around the ancient settlements of Orkney and Shetland, and end up in St. Andrews, where we’ll help the University celebrate its 600th anniversary. Then there’s unforgettable Iceland, and beyond lies the world’s largest island, Greenland, where we’ll watch giant icebergs calve and meet with the Greenlandic people. Further West, in the Canadian Arctic, or in rugged Labrador or music-filled Newfoundland, we’re on home ground, with expeditions that take us from Inuit art centres like Baffin Island’s Kinngait (Cape Dorset) all the way to The Northwest Passage. Our itineraries are thoughtfully designed to include areas of exceptional splendour, optimal wildlife viewing and historical significance. Our teams of experts – geologists, botanists, biologists, anthropologists and historians, as well as artists in words, music, painting and more – are there to make sure that we’ll all learn a lot, gaining insight into both the natural and the cultural landscape. -

Visitor Information Package to Arrive Prepared, to Identify Backcountry Challenges and to Plan an Enriching Arctic Experience, Please Read This Package Thoroughly

Visitor Information Package To arrive prepared, to identify backcountry challenges and to plan an enriching Arctic experience, please read this package thoroughly. 2019 For more information To reach park staff between September and early May, please contact Parks Canada in Iqaluit or visit our website. During the summer field season (approximately mid-May to mid-August), the Resolute office will assist you in connecting with field staff. Iqaluit office Hours of operation Resolute Bay office Phone: 867-975-4673 Year round Phone: 867-252-3000 Fax: 867-975-4674 Monday to Friday [email protected] 8:30 a.m. - 12 noon and 1 p.m. - 5 p.m. [email protected] Related websites Additional Resources: www.pc.gc.ca/quttinirpaaq Mirnguiqsirviit – Nunavut Territorial Parks: www.nunavutparks.com Nunavut Tourism: www.nunavuttourism.com Transport Canada: www.tc.gc.ca Weather Conditions: Resolute Bay: www.weatheroffice.gc.ca/city/pages/nu-27_metric_e.html Grise Fiord: www.weatheroffice.gc.ca/city/pages/nu-12_metric_e.html All photos copyright Parks Canada unless otherwise stated. 2019 Table of contents Welcome 2 Important information 3 - 4 Pre-trip, post-Trip, permits 3 Registration & de-registration 4 Planning your trip 5 Ukkusiksalik National Park map 5 Topographical maps 5 How to get here 6 - 7 Air access to Nunavut 6 Emergency medical travel 6 Travelling with dangerous goods 7 Community information 8 Local outfitters, visitor Information 8 Accommodations 8 Activities 9 - 11 Hiking and travelling to the North