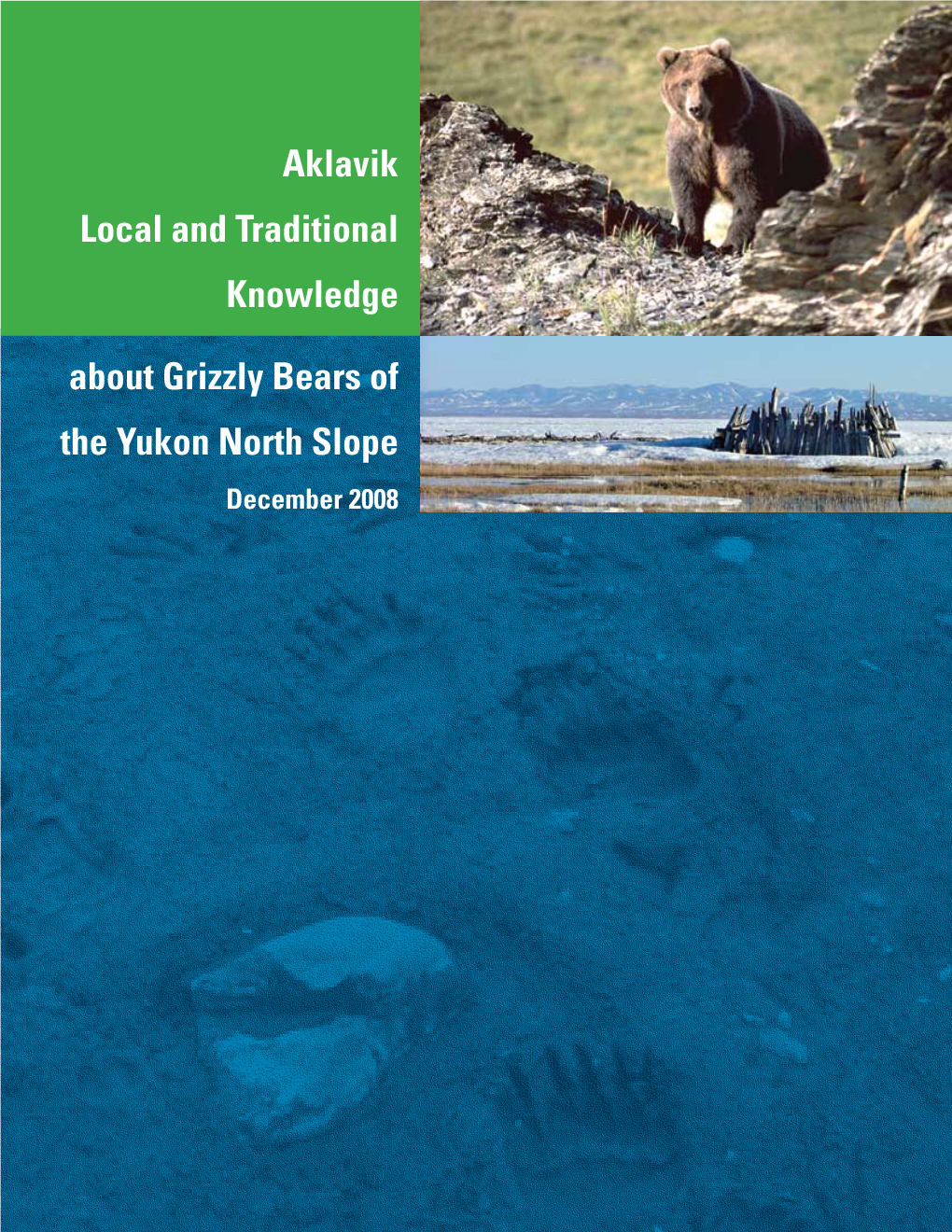

Aklavik Grizzly Bear Traditional Knowledge Study 1.81 MB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Update: March 23, 2020 Current Procedure

PUBLIC UPDATE: MARCH 23, 2020 Over the weekend, Town Administration, Staff, & Leadership have been involved in extensive communication and planning with our regional Government of the Northwest Territories personnel and administration. While we are responding to the evolving situation, our main focus has been on our procedure to how Inuvik will receive, monitor, house, & feed those returning to Inuvik from one of the smaller regional communities or those who do not have an adequate space at home to fulfill the requirements for the 14 days of required self-isolation. As you are now aware, the Chief Health Officer and the Government of the Northwest Territories now requires every person entering the Territory (including residents) to self-isolate for 14 days. Further to this, the GNWT requires those required to self-isolate to do so in one of the larger designated centres: Hay River, Yellowknife, Inuvik or Fort Smith. CURRENT PROCEDURE FOR THOSE ENTERING INUVIK BY ROAD OR BY AIR All persons returning to Inuvik from outside the Territory, by road or by air are now being screened at the point of entry. Whether you enter Inuvik via the Dempster Highway or the Inuvik Airport, you will be screened and directed in the following ways: 1. If you have not already, you are required to complete and submit a self-isolation plan to the GNWT. Link to Self-Isolation Plan Form Here. 2. If you are an Inuvik resident and are able to self-isolate at home, you will be directed to proceed directly to your home and stay there for the 14-day duration following all protocols as required by the Chief Health Officer. -

INUVIALUIT LANGUAGE and IDENTITY: PERSPECTIVES on the SYMBOLIC MEANING of INUVIALUKTUN in the CANADIAN WESTERN ARCTIC by Alexand

INUVIALUIT LANGUAGE AND IDENTITY: PERSPECTIVES ON THE SYMBOLIC MEANING OF INUVIALUKTUN IN THE CANADIAN WESTERN ARCTIC by Alexander C. Oehler B.A., University of Northern British Columbia, 2010 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA July 2012 © Alexander C. Oehler, 2012 Abstract: The revitalization of ancestral languages has been an issue of great concern to Aboriginal communities across North America for several decades. More recently, this concern has also found a voice in educational policy, particularly in regions where Aboriginal land claims have been ratified, and where public schools fall under a mandate to offer curricula that meet the needs of Aboriginal students. This research seeks to explore the cultural significance of Inuvialuktun, a regional Inuit language comprised of three distinct dialects traditionally spoken by the Inuvialuit of the northern Northwest Territories, Canada. More specifically, the research seeks to examine the role of current Inuvialuktun language revitalization efforts in the establishment of Inuvialuit collective and individual identities across several age groups. Tying into the sociolinguistic discourse on ancestral language revitalization in North America, the research seeks to contribute a case study from a region underrepresented in the literature on language and identity. The applied aim of the study is to provide better insight on existing language ideologies and language attitudes subscribed to by current and potential learners of Inuvialuktun in the community of Inuvik, NWT. Data obtained by the study is intended to aid local and territorial language planners in identifying potential obstacles and opportunities regarding language learner motivation. -

Northwest Territories Liquor Licensing Board 65Th Annual Report

TD 531-18(3) TABLED ON AUGUST 22, 2019 Northwest Territories Liquor Licensing Board 65th Annual Report 2018 - 2019 201 June 27th, 9 Honourable Robert C. McLeod Minister Responsible for the NWT Liquor Licensing Board Dear Honourable Minister McLeod: In accordance with the Liquor Act, I am pleased to present the Northwest Territories Liquor Licensing Board’s 201 - 201 Annual Report. 8 9 Sincerely, Sandra Aitken Chairperson Contents Chairperson’s Message ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Board Overview ..................................................................................................................................................... 2 Board Members and Staff .............................................................................................................................. 2 Board Activity ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Total Meetings ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Administration and Orientation Meetings .............................................................................................. 4 Licence Applications and Board Requests .............................................................................................. 4 Compliance Hearings ..................................................................................................................................... -

Environment and Natural Nt and Natural Resources

ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES Implementation Plan for the Action Plan for Boreal Woodland Caribou in the Northwest Territories: 2010-2015 The Action Plan for Boreal Woodland Caribou Conservation in the Northwest Territories was released after consulting with Management Authorities, Aboriginal organizations, communities, and interested stakeholders. This Implementation Plan is the next step of the Action Plan and will be used by Environment and Natural Resources to implement the actions in cooperation with the Tᰯch Government, Wildlife Management Boards and other stakeholders. In the future, annual status reports will be provided detailing the progress of the actions undertaken and implemented by Environment and Natural Resources. Implementation of these 21 actions will contribute to the national recovery effort for boreal woodland caribou under the federal Species at Risk Act . Implementation of certain actions will be coordinated with Alberta as part of our mutual obligations outlined in the signed Memorandum of Understanding for Cooperation on Managing Shared Boreal Populations of Woodland Caribou. This MOU acknowledges boreal caribou are a species at risk that are shared across jurisdictional lines and require co-operative management. J. Michael Miltenberger Minister Environment and Natural Resources IMPLEMENTATION PLAN Environment and Natural Resources Boreal Woodland Caribou Conservation in the Northwest Territories 2010–2015 July 2010 1 Headquarters Inuvik Sahtu North Slave Dehcho South Slave Action Initiative Involvement Region Region Region Region Region 1 Prepare and implement Co-lead the Dehcho Not currently Currently not Not currently To be developed To be developed comprehensive boreal caribou Boreal Caribou Working needed. needed. needed. by the Dehcho by the Dehcho range management plans in Group. -

Compendium of Research in the Northwest Territories 2014

Compendium of Research in the Northwest Territories 2014 www.nwtresearch.com This publication is a collaboration between the Aurora Research Institute, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre. Thank you to all who submitted a summary of research or photographs, and helped make this publication possible. Editor: Ashley Mercer Copyright © 2015 ISSN: 1205-3910 Printed by Aurora Research Institute Foreword Welcome to the 2014 Compendium of Research in the Northwest Territories. This year marked a special anniversary for the Aurora Research Institute and northern research. Fifty years ago, the Inuvik Research Laboratory was built and has served as a hub for research in the western arctic ever since. The Lab, as it was known, was first built as an initiative of the Canadian federal government in the newly established community of Inuvik. It remains on the same site today, but in 2011, a new modern multi-purpose facility opened to continue to support research in the north. We have included a brief history of the Lab and its impact in this edition of the Compendium to mark its long lasting importance to many researchers and community members. As part of the 50th anniversary celebration, the Aurora Research Institute team undertook a full set of NWT-wide celebrations. We celebrated the history, capacity and growth of research in the NWT that touched all corners of the territory and beyond. We honoured the significant scientific contributions that have taken place in the NWT over the past 50 years, and the role of NWT researchers, technicians and citizens in these accomplishments. -

Yukon Fisheries News a Publication of the Yukon River Drainage Fisheries Association Winter 2011

Yukon Fisheries News A Publication of the Yukon River Drainage Fisheries Association WINTER 2011 Yukon River Drainage Tribal Councils & First Nations Endure Fisheries Association A United Voice for Yukon River Fishers Constraining Issues By Teddy Willoya, Program Assistant the material into the environment. As a result, This winter I had the opportunity to some of the clams, mussels, herring eggs, tomcod, interview six communities on the Yukon River and other subsistence foods are carcinogenic. from the coast all the way to Canada about their Locals ask, “Are the foods around that area safe to Success Story: Everybody Loves Eels ······················· 4 most afflicting issues. In Alaska, I spoke with harvest anymore?” High unemployment for most of Tribal Council members from Scammon Bay, St. the members of the community is also a concern. Voices from the River ············· 5 Mary’s, Holy Cross, and Eagle. On the Canadian St. Mary’s expressed some interesting How Does Fisheries Management side of the drainage, I spoke with directors from concerns. Unemployment is the top community Work in Canada? ················· 7 Dawson and Little Salmon. All six communities issue. Many people there are unemployed, and 2011 Yukon River Chinook Salmon I interviewed had big issues that need to be most applicants are not qualified to operate the Rebuilding Initiative ············· 7 addressed. programs and services offered in the community. Telling the Future: The Science The majority of the issues were related to It is a goal of the community to implement job Behind Salmon Run Forecasting ··· 8 environmental concerns, low king salmon returns, high unemployment, and landfill issues. -

Country Food Sharing Networks, Household Structure, and Implications for Understanding Food Insecurity in Arctic Canada Peter Collingsa, Meredith G

ECOLOGY OF FOOD AND NUTRITION http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03670244.2015.1072812 Country food sharing networks, household structure, and implications for understanding food insecurity in Arctic Canada Peter Collingsa, Meredith G. Martena, Tristan Pearceb, and Alyson G. Youngc aDepartment of Anthropology, University of Florida, Florida, USA; bUniversity of the Sunshine Coast, Sippy Downs, Australia; cDepartment of Anthropology, University of Florida, Florida, USA ABSTRACT KEYWORDS We examine the cultural context of food insecurity among Food security; food sharing; Inuit in Ulukhaktok, Northwest Territories, Canada. An analysis industrial foods; Inuit; of the social network of country food exchanges among 122 traditional foods households in the settlement reveals that a household’s betweenness centrality—a measure of brokerage—in the country food network is predicted by the age of the house- hold. The households of married couples were better posi- tioned within the sharing network than were the households of single females or single males. Households with an active hunter or elder were also better positioned in the network. The households of single men and women appear to experience limited access to country food, a considerable problem given the increasing number of single-adult households over time. We conclude that the differences between how single women and single men experience constrained access to country foods may partially account for previous findings that single women in arctic settlements appear to be at particular risk for food insecurity. Introduction For many Canadian Inuit, country foods—foods acquired by hunting, fish- ing, trapping, or collecting—remain central to their diets despite decades of social, economic, and political changes. -

Inuvialuit For

D_156905_inuvialuit_Cover 11/16/05 11:45 AM Page 1 UNIKKAAQATIGIIT: PUTTING THE HUMAN FACE ON CLIMATE CHANGE PERSPECTIVES FROM THE INUVIALUIT SETTLEMENT REGION UNIKKAAQATIGIIT: PUTTING THE HUMAN FACE ON CLIMATE CHANGE PERSPECTIVES FROM THE INUVIALUIT SETTLEMENT REGION Workshop Team: Inuvialuit Regional Corporation (IRC), Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK), International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), Centre Hospitalier du l’Université du Québec (CHUQ), Joint Secretariat: Inuvialuit Renewable Resource Committees (JS:IRRC) Funded by: Northern Ecosystem Initiative, Environment Canada * This workshop is part of a larger project entitled Identifying, Selecting and Monitoring Indicators for Climate Change in Nunavik and Labrador, funded by NEI, Environment Canada This report should be cited as: Communities of Aklavik, Inuvik, Holman Island, Paulatuk and Tuktoyaktuk, Nickels, S., Buell, M., Furgal, C., Moquin, H. 2005. Unikkaaqatigiit – Putting the Human Face on Climate Change: Perspectives from the Inuvialuit Settlement Region. Ottawa: Joint publication of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, Nasivvik Centre for Inuit Health and Changing Environments at Université Laval and the Ajunnginiq Centre at the National Aboriginal Health Organization. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Naitoliogak . 1 1.0 Summary . 2 2.0 Acknowledgements . 3 3.0 Introduction . 4 4.0 Methods . 4 4.1 Pre-Workshop Methods . 4 4.2 During the Workshop . 5 4.3 Summarizing Workshop Observations . 6 5.0 Observations. 6 5.1 Regional (Common) Concerns . 7 Changes to Weather: . 7 Changes to Landscape: . 9 Changes to Vegetation: . 10 Changes to Fauna: . 11 Changes to Insects: . 11 Increased Awareness And Stress: . 11 Contaminants: . 11 Desire For Organization: . 12 5.2 East-West Discrepancies And Patterns . 12 Changes to Weather . -

Community Resistance Land Use And

COMMUNITY RESISTANCE LAND USE AND WAGE LABOUR IN PAULATUK, N.W.T. by SHEILA MARGARET MCDONNELL B.A. Honours, McGill University, 1976 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Geography) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 1983 G) Sheila Margaret McDonnell, 1983 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 DE-6 (3/81) ABSTRACT This paper discusses community resistance to the imposition of an external industrial socio-economic system and the destruction of a distinctive land-based way of life. It shows how historically Inuvialuit independence has been eroded by contact with the external economic system and the assimilationist policies of the government. In spite of these pressures, however, the Inuvialuit have struggled to retain their culture and their land-based economy. This thesis shows that hunting and trapping continue to be viable and to contribute significant income, both cash and income- in-kind to the community. -

Community Food Program Use in Inuvik, Northwest Territories James D Ford1*, Marie-Pierre Lardeau1, Hilary Blackett2, Susan Chatwood2 and Denise Kurszewski2

Ford et al. BMC Public Health 2013, 13:970 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/13/970 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Community food program use in Inuvik, Northwest Territories James D Ford1*, Marie-Pierre Lardeau1, Hilary Blackett2, Susan Chatwood2 and Denise Kurszewski2 Abstract Background: Community food programs (CFPs) provide an important safety-net for highly food insecure community members in the larger settlements of the Canadian Arctic. This study identifies who is using CFPs and why, drawing upon a case study from Inuvik, Northwest Territories. This work is compared with a similar study from Iqaluit, Nunavut, allowing the development of an Arctic-wide understanding of CFP use – a neglected topic in the northern food security literature. Methods: Photovoice workshops (n=7), a modified USDA food security survey and open ended interviews with CFP users (n=54) in Inuvik. Results: Users of CFPs in Inuvik are more likely to be housing insecure, female, middle aged (35–64), unemployed, Aboriginal, and lack a high school education. Participants are primarily chronic users, and depend on CFPs for regular food access. Conclusions: This work indicates the presence of chronically food insecure groups who have not benefited from the economic development and job opportunities offered in larger regional centers of the Canadian Arctic, and for whom traditional kinship-based food sharing networks have been unable to fully meet their dietary needs. While CFPs do not address the underlying causes of food insecurity, they provide an important service -

Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve Table of Contents

Annual Report 2008 Yukon-CharleyYukon-Charley RiversRivers NationalNational PreservePreserve National Park Service Department of the Interior There’s a land where the mountains are nameless, And the rivers all run God knows where; There are lives that are erring and aimless, And deaths that just hang by a hair; There are hardships that nobody reckons; There’s a land - oh, it beckons and beckons, And I want to go back - and I will. Robert Service, from The Spell of the Yukon 2 Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve Table of Contents Purpose and Significance of Yukon-CharleyRivers National Preserve................................................................4 Map of Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve.................................................................................................5 Message from the Superintendent......................................................................................................................6 Performance and Results Section.................................................................................................................7-25 Preserve Resources............................................................................................................................7-20 Public Enjoyment and Visitor Experience.....................................................................................21-25 FY 2008 Financial Summary.............................................................................................................................26 Preserve Organization......................................................................................................................................27 -

Documenting Linguistic Knowledge in an Inuit Language Atlas

Document generated on 10/01/2021 7:23 p.m. Études Inuit Studies Documenting Linguistic Knowledge in an Inuit Language Atlas Documenter les connaissances linguistiques dans un atlas en langue inuit Kumiko Murasugi and Monica Ittusardjuat Curriculum scolaire inuit Article abstract Inuit School Curriculum The traditional method of orally transmitting language is weakening with the Volume 40, Number 2, 2016 passing of fluent Elders and language erosion in contemporary Inuit society. Language documentation is a vital component of language maintenance and URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1055437ar revitalization. In this paper we present a pilot online, multimedia DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1055437ar cybercartographic Atlas of the Inuit Language in Canada, the goal of which is to help protect and strengthen the vitality of Inuit dialects through the documentation of their words. The main component of the atlas is a See table of contents multidialectal database of written and spoken words. We discuss the role of dictionaries in language documentation, introduce the features of the atlas, explore the appeal of the atlas to different types of users (in particular, Publisher(s) language learners), and present future directions for the atlas project. Centre interuniversitaire d’études et de recherches autochtones (CIÉRA) ISSN 0701-1008 (print) 1708-5268 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Murasugi, K. & Ittusardjuat, M. (2016). Documenting Linguistic Knowledge in an Inuit Language Atlas. Études Inuit Studies, 40(2), 169–190. https://doi.org/10.7202/1055437ar Tous droits réservés © La revue Études Inuit Studies, 2019 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online.