The Increasing Demand of Intellectual Property Protection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Μitron 4.0 Specification (Ver. 4.03.00) TEF024-S001-04.03.00/En July 2010 Copyright © 2010 by T-Engine Forum

μITRON 4.0 Specification Ver. 4.03.00 TEF024-S001-04.03.00/en July 2010 μITRON 4.0 Specification (Ver. 4.03.00) TEF024-S001-04.03.00/en July 2010 Copyright © 2010 by T-Engine Forum. This “μITRON 4.0 Specification (Ver. 4.03.00)” was originally released by TRON ASSOCIATION which has been integrated into T-Engine Forum since January 2010. The same specification now has been released by T-Engine Forum as its own specification without modification of the content after going through the IPR procedures. T-Engine Forum owns the copyright of this specification. Permission of T-Engine Forum is necessary for copying, republishing, posting on servers, or redistribution to lists of the contents of this specification. The contents written in this specification may be changed without a prior notice for improvement or other reasons in the future. About this specification, please refer to follows; Publisher T-Engine Forum The 28th Kowa Building 2-20-1 Nishi-gotanda Shinagawa-Ward Tokyo 141-0031 Japan TEL:+81-3-5437-0572 FAX:+81-3-5437-2399 E-mail:[email protected] TEF024-S001-04.03.00/en µITRON4.0 Specification Ver. 4.03.00 Supervised by Ken Sakamura Edited and Published by TRON ASSOCIATION µITRON4.0 Specification (Ver. 4.03.00) The copyright of this specification document belongs to TRON Association. TRON Association grants the permission to copy the whole or a part of this specification document and to redistribute it intact without charge or at cost. However, when a part of this specification document is redistributed, it must clearly state (1) that it is a part of the µITRON4.0 Specification document, (2) which part was taken, and (3) the method to obtain the whole specification document. -

Compact, Low-Cost, but Real-Time Distributed Computing for Computer Augmented Environments

Compact, Low-Cost, but Real-Time Distributed Computing for Computer Augmented Environments Hiroaki Takada and Ken Sakamura Department of Information Science, Faculty of Science, University of Tokyo 7-3-1, Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113, Japan Abstract We have been conducting a research and development project, called the TRON Project, for realizingthe computer augmented environments. The final goal of the project is to realize highly functionally distributed systems (HFDS) in which every kind of objects around our daily life are augmented with embedded computers, be connected with networks, and cooperate each other to provide better living environments for human beings. One of the key technologies towards HFDS is the realization methods of compact and low-cost distributed computing systems with dependability and real-time property. In this paper, the overview of the TRON Project are introduced and various research and development activities for realizing HFDS, especially the subprojects on a standard real- time kernel specification for small-scale embedded systems Figure 1: Computerized Living Environment called ITRON and on a low-cost real-time LAN called "ITRON bus, are described. We also describe the future A typical example of “computing everywhere” envi- directions of the project centered on the TRON-concept ronment is the TRON-concept Intelligent House, which Computer Augmented Building, which is a pilot realization was built experimentally in 1989 (Figure 2). The purpose of HFDS and being planned to be built. was to create a testbed for future intensively computerized living spaces. The house with 330 m2 of floor space was 1 Introduction equipped with around 1000 computers, sensors, and actu- ators, which were loosely connected to form a distributed Recent advances in microprocessor technologies have computing system. -

Japanese Semiconductor Industry Conference

Japanese Semiconductor Industry Conference April 11-12, 1988 Hotel Century Hyatt Tokyo, J^an Dataoyest nn aaxraiaiwof JED IneOun&BradstRetCorpofation 1290 Ridder Plark Drive San Jose, CaUfonm 95131-2398 (408) 437-8000 Telex: 171973 Fax: (408) 437-0292 Sales/Service Offices: UNITED KINGDOM FRANCE EASTERN U.S. Dataquest UK Limited Damquest SARL Dataquest Boston 13th Floor, Ceittiepoint Tour Gallieni 2 1740 Massachusetts Ave. 103 New Oxford Street 36, avenue GaUieni Boxborough, MA 01719 London WCIA IDD 93175 Bagnolet Cedex (617) 264-4373 England France Tel«: 171973 01-379-6257 (1)48 97 31 00 Fax: (617) 263-0696 Tfelex: 266195 Tfelex: 233 263 Fax: 01-240-3653 Fax: (1)48 97 34 00 GERMANY JAPAN KOREA Dataquest GmbH Dataquest Js^an, Ltd. Dataquest Korea Rosenkavalierplatz 17 Tkiyo Ginza Building/2nd Floor 63-1 Chungjung-ro, 3Ka D-8000 Munich 81 7-14-16 Ginza, Chuo-ku Seodaemun-ku ^^fest Germany Tbkyo 104 Japan Seoul, Korea (089)91 10 64 (03)546-3191 (02)392-7273-5 Tfelex: 5218070 Tfelex: 32768 Telex: 27926 Fax: (089)91 21 89 Fax: (03)546-3198 Fax: (02)745-3199 The content of this report represents our interpretation aiKl analysis of information generally avail able to the public or released by responsible indivi(bials in the subject companies, but is not guaranteed as to accuracy or comfdeteness. It does not contain material provided to us in confidence t^ our clients. This information is not furnished in connection with a sale or offer to sell securities, or in coimec- tion with the solicitation of an offer to buy securities. -

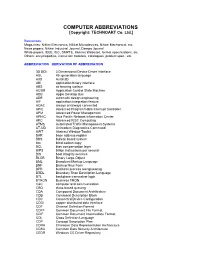

COMPUTER ABBREVIATIONS [Copyright: TECHNOART Co

COMPUTER ABBREVIATIONS [Copyright: TECHNOART Co. Ltd.] References: Magazines: Nikkei Electronics, Nikkei Microdevices, Nikkei Mechanical, etc. News papers: Nikkei Industrial Journal, Dempa Journal White papers: IEEE, IEC, SMPTE, Internet Websites, format specifications, etc. Others: encyclopedias, instruction booklets, catalogues, product spec., etc. ABBREVIATION DERIVATION OF ABBREVIATION 3D DDI 3 Dimensional Device Driver Interface 4GL 4th generation language A3D Aural 3D ABI application binary interface ABS air bearing surface ACSM Application Control State Machine ADB Apple Desktop Bus ADE automatic design engineering AIF application integration feature AOAC always on/always connected APIC Advanced Programmable Interrupt Controller APM Advanced Power Management APNIC Asia Pacific Network Information Center ARC Advanced RISC Computing ATMS Automated Traffic Management Systems AT-UD Unimodem Diagnostics Command AWT Abstract Window Toolkit BAR base address register BBS bulletin board system bcc blind carbon copy BCL bias compensation layer BIPS billion instructions per second BIS boot integrity services BLOB Binary Large Object BML Broadcast Markup Language BNF Backup Naur Form BPR business process reengineering BSDL Boundary Scan Description Language BTL backplane transceiver logic BTRON Business TRON C&C computer and communication CBQ class-based queuing CDA Compound Document Architecture CDB Command Description Block CDC Connected Device Configuration CDDI copper distributed data interface CDF Channel Definition Format CDFF Common -

Μitron4.0 Specification (Ver

µITRON4.0 Specification Ver. 4.00.00 ITRON Committee, TRON ASSOCIATION Supervised by Ken Sakamura Edited by Hiroaki Takada Copyright (C) 1999, 2002 by TRON ASSOCIATION, JAPAN µITRON4.0 Specification (Ver. 4.00.00) The copyright of this specification document belongs to the ITRON Committee of the TRON Association. The ITRON Committee of the TRON Association grants the permission to copy the whole or a part of this specification document and to redistribute it intact without charge or with a distribution fee. However, when a part of this specification document is redistributed, it must clearly state (1) that it is a part of the µITRON4.0 Specification document, (2) which part it was taken, and (3) the method to obtain the whole specifi- cation document. See Section 6.1 for more information on the conditions for using this specification and this specification document. Any questions regarding this specification and this specification document should be directed to the following: ITRON Committee, TRON Association Katsuta Building 5F 3-39, Mita 1-chome, Minato-ku, Tokyo 108-0073, JAPAN TEL: +81-3-3454-3191 FAX: +81-3-3454-3224 § TRON is the abbreviation of “The Real-time Operating system Nucleus.” § ITRON is the abbreviation of “Industrial TRON.” § µITRON is the abbreviation of “Micro Industrial TRON.” § BTRON is the abbreviation of “Business TRON.” § CTRON is the abbreviation of “Central and Communication TRON.” § TRON, ITRON, µITRON, BTRON, and CTRON do not refer to any specific product or products. µITRON4.0 Specification Ver. 4.00.00 A Word from the Project Leader Fifteen years have passed since the ITRON Sub-Project started as a part of the TRON Project: a real-time operating system specification for embedded equipment control. -

T-Engine 2O11

T-Engine 2O11 by Ken SAKAMURA Professor, The University of Tokyo Interfaculty Initiative in Information Studies Graduate School of The University of Tokyo Chair, T-Engine Forum / uID Center Chairman,YRP Ubiquitous Networking Laboratory IEEE Fellow Contact T-Engine Forum The 28th KOWA Bldg. 2-20-1, Nishi Gotanda, Shinagawa, Tokyo 141-0031 Japan TEL: +81-3-5437-0572 / FAX: +81-3-5437-2399 E-mail: [email protected] Contents T2 2 1 Evolving TRON 2 1.1 μT-Kernel 3 1.2 MP T-Kernel 3 2 From T-Kernel 1.0 to T-Kernel 2.0 4 2.1 Significant Enhancement of Time Control Functions 4 2.2 Large Capacity Device Support 5 2.3 Enhancement of System Management Functions and Utility Functions 5 2.4 Upward Compatibility of T-Kernel 1.0 6 3 One Stop Service 6 4 Electronic Document of the T-Kernel 2.0 Specification 6 5 T2 7 T-License 2.0 8 T-Kernel Traceability Service 9 The TRON Engineer Certification Examination 10 Questionnaire Survey on Embedded Real-time OS Usage Trend 11 Adoption example / Application example 11 Products with T-Kernel μITRON specification OS (including JTRON) 11 T-Kernel, μT-Kernel specification OS and Development Environment 15 Middleware and Development Kit with T-Kernel 17 T-Engine Related Software 19 T-Kernel Related Products 19 μITRON specification OS and Development Tools 20 BTRON, etc. 21 T-Engine Forum Admission Guide 22 Member Organization List 31 T-Engine T2 —T-Engine Project on to the Second Stage specification OS requiring peripheral functions such as 1 Evolving TRON file management and device management increased, and companies began to enhance ITRON with their The TRON Project, launched in 1984, is a own middleware. -

Ieee Computer Society Style Guide

IEEE COMPUTER SOCIETY STYLE GUIDE Style Guide version October 2016 Table of Contents Introduction 1 Mission statement General information Resolving differences with authors Acknowledgments Abbreviations 3 Acronyms and Abbreviated Terms 5 Authors and Affiliations 6 Best Practices 7 Abstracts Acknowledgments Article titles Figures File and folder conventions Main text Sidebars Tables URLs Biographical Sketches 12 Capitalization 13 Internal capitals Titles Department names Copyrights, Trademarks, US Government Work, and Image Permissions 14 File Extensions and Their Meanings 15 Lists 16 Locations 18 Standard and postal abbreviations: US states and Canadian provinces Postal code placement Mathematical Expressions 22 Miscellaneous math style issues Equation formatting guidelines Math guidelines Non-English Words and Phrases 26 Numbers and Symbols 27 Dates Numerals Symbols and signs Telephone and fax numbers Program Code 29 Punctuation Capitalization Tokens in text Punctuation 31 Colons Ellipses Em dashes En dashes Quotation marks Slashes (virgules) References 32 Sample formats General style Alphabetical Listing 41 Usages not identified or adequately defined in accepted external sources Introduction Mission statement The IEEE Computer Society Style Guide Committee’s mission is to clarify the editorial styles and standards that the Society’s publications use. We maintain and periodically update a style guide to clarify those usages not adequately defined in accepted external sources. Our purpose is to promote coherence, consistency, and identity of style, making it easier for CS editors and our authors to produce quality submissions and publications that communicate clearly to all our readers. General information This revised (October 2016) edition of the IEEE Computer Society Style Guide complements these primary references: Preferred dictionary: Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 11th ed., 2003. -

Economic Impact of Technology Standards Annexes to the Report

Economic Impact of Technology Standards Annexes to the Report The past and the road ahead October 2017 Authors: Jorge Padilla, John Davies and Aleksandra Boutin compasslexecon.com This report was commissioned by Qualcomm Incorporated. All opinions expressed here are those of the authors, who are all employees of Compass Lexecon: Jorge Padilla, John Davies and Aleksandra Boutin, supported by Anubhav Mohanty and Sabire Ipek Demir. Contents COMpaSS LEXEcoN Economic Impact of Technology Standards The past and the road ahead Contents Annex A Case Study: Mobile Telephony 1 Introduction 1 Historical overview 1 First generation mobile telephone systems 2 2G mobile telephone systems 3 Evolution of standard setting from 2G to 4G 7 The evolution of the mobile telephony ecosystem 11 Summary and conclusions 23 Annex B Case Study: TV Standards 25 Introduction 25 Key components of a TV system 25 The colour war: RCA v. CBS in the US 26 Global fragmentation in analogue colour TV standards: PAL, SECAM and NTSC 27 High Definition television standards and the switch to Digital Television 31 Summary and conclusions 39 Annex C Case Study: PC Operating Systems 41 Introduction 41 Technological stack and O/S 41 The development of operating systems for PCs 41 Effects of proprietary control of the operating system 51 Evolution of O/S market structure and innovation 53 Impact on average prices 55 Summary and conclusions 56 Annex A COMpaSS LEXEcoN Case Study: Economic Impact of Technology Standards 1 Mobile Telephony The past and the road ahead Case Study: Mobile Telephony Introduction A.3 In this annex we therefore provide a more detailed account of the history of technological, commercial and institutional A.1 Mobile telephony is an industry very heavily dependent developments in the mobile telephony industry, with a on technological standards. -

Tangible Interfaces for Manipulating Aggregates of Digital Information

Tangible Interfaces for Manipulating Aggregates of Digital Information Brygg Anders Ullmer Bachelor of Science, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, January 1995 Master of Science, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, June 1997 Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences, School of Architecture and Planning, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September 2002 © Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2002 All Rights Reserved _____________________________________________________ Author Brygg Anders Ullmer Program in Media Arts and Sciences August 9, 2002 _____________________________________________________ Certified by Hiroshi Ishii Associate Professor of Media Arts and Sciences Thesis Supervisor _____________________________________________________ Accepted by Andrew B. Lippman Chair, Departmental Committee for Graduate Students Program in Media Arts and Sciences Tangible Interfaces for Manipulating Aggregates of Digital Information Brygg Anders Ullmer Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences, School of Architecture and Planning, on August 9, 2002 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Media Arts and Sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Abstract This thesis develops new approaches for people to physically represent and interact with aggregates of digital information. These support the concept of Tangible User Interfaces (TUIs), a genre of human-computer interaction that uses spatially reconfigurable physical objects as representations and controls for digital information. The thesis supports the manipulation of information aggregates through systems of physical tokens and constraints. In these interfaces, physical tokens act as containers and parameters for referencing digital information elements and aggregates. Physical constraints are then used to map structured compositions of tokens onto a variety of computational interpretations.