Ground Maneuver and Air Interdiction a Matter of Mutual Support at the Operational Level of War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Citizens and Soldiers in the Siege of Yorktown

Citizens and Soldiers in the Siege of Yorktown Introduction During the summer of 1781, British general Lord Cornwallis occupied Yorktown, Virginia, the seat of York County and Williamsburg’s closest port. Cornwallis’s commander, General Sir Henry Clinton, ordered him to establish a naval base for resupplying his troops, just after a hard campaign through South and North Carolina. Yorktown seemed the perfect choice, as at that point, the river narrowed and was overlooked by high bluffs from which British cannons could control the river. Cornwallis stationed British soldiers at Gloucester Point, directly opposite Yorktown. A British fleet of more than fifty vessels was moored along the York River shore. However, in the first week of September, a French fleet cut off British access to the Chesapeake Bay, and the mouth of the York River. When American and French troops under the overall command of General George Washington arrived at Yorktown, Cornwallis pulled his soldiers out of the outermost defensive works surrounding the town, hoping to consolidate his forces. The American and French troops took possession of the outer works, and laid siege to the town. Cornwallis’s army was trapped—unless General Clinton could send a fleet to “punch through” the defenses of the French fleet and resupply Yorktown’s garrison. Legend has it that Cornwallis took refuge in a cave under the bluffs by the river as he sent urgent dispatches to New York. Though Clinton, in New York, promised to send aid, he delayed too long. During the siege, the French and Americans bombarded Yorktown, flattening virtually every building and several ships on the river. -

The Law of Victory and the Making of Modern War Robert Sloane Boston Univeristy School of Law

Boston University School of Law Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law Faculty Scholarship 8-22-2013 Book Review of The eV rdict of Battle: The Law of Victory and the Making of Modern War Robert Sloane Boston Univeristy School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the International Humanitarian Law Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Robert Sloane, Book Review of The Verdict of Battle: The Law of Victory and the Making of Modern War, No. 13-29 Boston University School of Law, Public Law Research Paper (2013). Available at: https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/faculty_scholarship/24 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REVIEW OF JAMES Q. WHITMAN, THE VERDICT OF BATTLE: THE LAW OF VICTORY AND THE MAKING OF MODERN WAR (2012) Boston University School of Law Worrking Paper No. 13-39 (August 22, 2013) Robert D. Sloane Boston University Schoool of Law This paper can be downloaded without charge at: http://www.bu.edu/law/faculty/scholarship/workingpapers/2013.html The Verdict of Battle: The Law of Victory and the Making of Modern War. By James Q. Whitman. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012. Pp. vii, 323. Index. For evident reasons, scholarship on the law of war has been a growth industry for the past two decades. -

A Historical Assessment of Amphibious Operations from 1941 to the Present

CRM D0006297.A2/ Final July 2002 Charting the Pathway to OMFTS: A Historical Assessment of Amphibious Operations From 1941 to the Present Carter A. Malkasian 4825 Mark Center Drive • Alexandria, Virginia 22311-1850 Approved for distribution: July 2002 c.. Expedit'onaryyystems & Support Team Integrated Systems and Operations Division This document represents the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the Department of the Navy. Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. Specific authority: N0014-00-D-0700. For copies of this document call: CNA Document Control and Distribution Section at 703-824-2123. Copyright 0 2002 The CNA Corporation Contents Summary . 1 Introduction . 5 Methodology . 6 The U.S. Marine Corps’ new concept for forcible entry . 9 What is the purpose of amphibious warfare? . 15 Amphibious warfare and the strategic level of war . 15 Amphibious warfare and the operational level of war . 17 Historical changes in amphibious warfare . 19 Amphibious warfare in World War II . 19 The strategic environment . 19 Operational doctrine development and refinement . 21 World War II assault and area denial tactics. 26 Amphibious warfare during the Cold War . 28 Changes to the strategic context . 29 New operational approaches to amphibious warfare . 33 Cold war assault and area denial tactics . 35 Amphibious warfare, 1983–2002 . 42 Changes in the strategic, operational, and tactical context of warfare. 42 Post-cold war amphibious tactics . 44 Conclusion . 46 Key factors in the success of OMFTS. 49 Operational pause . 49 The causes of operational pause . 49 i Overcoming enemy resistance and the supply buildup. -

The Crucial Development of Heavy Cavalry Under Herakleios and His Usage of Steppe Nomad Tactics Mark-Anthony Karantabias

The Crucial Development of Heavy Cavalry under Herakleios and His Usage of Steppe Nomad Tactics Mark-Anthony Karantabias The last war between the Eastern Romans and the Sassanids was likely the most important of Late Antiquity, exhausting both sides economically and militarily, decimating the population, and lay- ing waste the land. In Heraclius: Emperor of Byzantium, Walter Kaegi, concludes that the Romaioi1 under Herakleios (575-641) defeated the Sassanian forces with techniques from the section “Dealing with the Persians”2 in the Strategikon, a hand book for field commanders authored by the emperor Maurice (reigned 582-602). Although no direct challenge has been made to this claim, Trombley and Greatrex,3 while inclided to agree with Kaegi’s main thesis, find fault in Kaegi’s interpretation of the source material. The development of the katafraktos stands out as a determining factor in the course of the battles during Herakleios’ colossal counter-attack. Its reforms led to its superiority over its Persian counterpart, the clibonarios. Adoptions of steppe nomad equipment crystallized the Romaioi unit. Stratos4 and Bivar5 make this point, but do not expand their argument in order to explain the victory of the emperor over the Sassanian Empire. The turning point in its improvement seems to have taken 1 The Eastern Romans called themselves by this name. It is the Hellenized version of Romans, the Byzantine label attributed to the surviving East Roman Empire is artificial and is a creation of modern historians. Thus, it is more appropriate to label them by the original version or the Anglicized version of it. -

C-130J-Sof International Special Operations Forces Configurations

C-130J-SOF INTERNATIONAL SPECIAL OPERATIONS FORCES CONFIGURATIONS Lockheed Martin Aeronautics Company 86 South Cobb Drive Marietta, Georgia 30063 www.lockheedmartin.com MG170335-003 © 2017 Lockheed Martin Corporation. All rights reserved. PIRA# AER201706008 When the need for security cannot be compromised, a PROVEN solution must be selected. With increasing and evolving global threats, precise use of POWER provides security. In a confusing and rapidly-changing environment, PRECISION and SKILL are force multipliers for peace. These are the moments and missions where failure is not an option. Now is when special operations forces (SOF) are called upon toPROTECT your today and your tomorrows. There is one solution that fully supports all special missions needs, fferingo versatility, endurance, command and control, surveillance and protection. Feared by enemies. Guardian of friendly forces. A global force multiplier. It is the world’s ultimate special missions asset. INTRODUCING THE C-130J-SOF. THE NEWEST MEMBER OF THE SUPER HERCULES FAMILY. SPECIAL OPERATIONS AIRCRAFT FOR THE 21ST CENTURY The C-130J-SOF provides specialized intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) support, along with infiltration, C-130J-SOF exfiltration, and re-supply of special operations forces (SOF) and equipment in hostile or denied territory. With added special mission equipment options, the C-130J-SOF may be configured to execute armed overwatch, precision strike, helicopter and vertical lift aerial refueling, psychological operations, high-speed/low-signature -

Barry Strauss

Faith for the Fight BARRY STRAUSS At a recent academic conference on an- cient history and modern politics, a copy of Robert D. Ka- plan’s Warrior Politics was held up by a speaker as an example of the current influence of the classics on Washing- ton policymakers, as if the horseman shown on the cover was riding straight from the Library of Congress to the Capitol.* One of the attendees was unimpressed. He de- nounced Kaplan as a pseudo-intellectual who does more harm than good. But not so fast: it is possible to be skeptical of the first claim without accepting the second. Yes, our politicians may quote Kaplan more than they actually read him, but if they do indeed study what he has to say, then they will be that much the better for it. Kaplan is not a scholar, as he admits, but there is nothing “pseudo” about his wise and pithy book. Kaplan is a journalist with long experience of living in and writing about the parts of the world that have exploded in recent decades: such places as Bosnia, Kosovo, Sierra Leone, Russia, Iran, Afghanistan, India, and Pakistan. Anyone who has made it through those trouble spots is more than up to the rigors of reading about the Peloponnesian War, even if he doesn’t do so in Attic Greek. A harsh critic might complain about Warrior Politics’ lack of a rigorous analytical thread, but not about the absence of a strong central thesis. Kaplan is clear about his main point: we will face our current foreign policy crises better by going *Robert D. -

Countersea Operations

COUNTERSEA OPERATIONS Air Force Doctrine Document 2-1.4 15 September 2005 This document complements related discussion found in Joint Publication 3-30, Command and Control for Joint Air Operations. BY ORDER OF THE AIR FORCE DOCTRINE DOCUMENT 2-1.4 SECRETARY OF THE AIR FORCE 15 SEPTEMBER 2005 SUMMARY OF REVISIONS This document is substantially revised. This revision’s overarching changes are new chapter headings and sections, terminology progression to “air and space” from “aerospace,” expanded discussion on planning and employment factors, operational considerations when conducting countersea operations, and effects-based methodology and the emphasis on operations vice capabilities or platforms. Specific changes with this revision are the additions of the naval warfighter’s perspective to enhance understanding the environment, doctrine, and operations of the maritime forces on page 3; comparison between Air Force and Navy/Marine Corp terminology, on page 7, included to ensure Air Force forces are aware of the difference in terms or semantics; a terminology matrix added to simplify that awareness on page 9; amphibious operations organization, command and control, and planning are also included throughout the document. Supersedes: AFDD 2-1.4, 4 June 1999 OPR: HQ AFDC/DS (Lt Col Richard Hughey) Certified by: AFDC/DR (Lt Col Eric Schnitzer) Pages: 66 Distribution: F Approved by: Bentley B. Rayburn, Major General, USAF Commander, Headquarters Air Force Doctrine Center FOREWORD Countersea Operations are about the use of Air Force capabilities in the maritime environment to accomplish the joint force commander’s objectives. This doctrine supports DOD Directive 5100.1 requirements for surface sea surveillance, anti-air warfare, anti-surface ship warfare, and anti-submarine warfare. -

JP 3-03, Joint Interdiction

Joint Publication 3-03 Joint Interdiction 14 October 2011 PREFACE 1. Scope This publication provides doctrine for planning, preparing, executing, and assessing joint interdiction operations. 2. Purpose This publication has been prepared under the direction of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. It sets forth joint doctrine to govern the activities and performance of the Armed Forces of the United States in joint operations and provides the doctrinal basis for interagency coordination and for US military involvement in multinational operations. It provides military guidance for the exercise of authority by combatant commanders and other joint force commanders (JFCs) and prescribes joint doctrine for operations, education, and training. It provides military guidance for use by the Armed Forces in preparing their appropriate plans. It is not the intent of this publication to restrict the authority of the JFC from organizing the force and executing the mission in a manner the JFC deems most appropriate to ensure unity of effort in the accomplishment of the overall objective. 3. Application a. Joint doctrine established in this publication applies to the joint staff, commanders of combatant commands, subunified commands, joint task forces, subordinate components of these commands, and the Services. b. The guidance in this publication is authoritative; as such, this doctrine will be followed except when, in the judgment of the commander, exceptional circumstances dictate otherwise. If conflicts arise between the contents of this publication and the contents of Service publications, this publication will take precedence unless the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, normally in coordination with the other members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, has provided more current and specific guidance. -

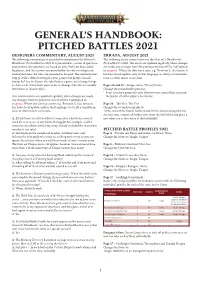

General's Handbook: Pitched Battles 2021

® GENERAL’S HANDBOOK: PITCHED BATTLES 2021 DESIGNERS COMMENTARY, AUGUST 2021 ERRATA, AUGUST 2021 The following commentary is intended to complement the General’s The following errata correct errors in the General’s Handboook: Handbook: Pitched Battles 2021. It is presented as a series of questions Pitched Battles 2021. The errata are updated regularly; when changes and answers; the questions are based on ones that have been asked are made, any changes from the previous version will be highlighted by players, and the answers are provided by the rules writing team in magenta. Where the date has a note, e.g. ‘Revision 2’, this means it and explain how the rules are intended to be used. The commentaries has had a local update, only in that language, to clarify a translation help provide a default setting for your games, but players should issue or other minor correction. always feel free to discuss the rules before a game, and change things as they see fit if they both want to do so (changes like this are usually Pages 24 and 25 – Savage Gains, Victory Points referred to as ‘house rules’). Change the second bullet point to: ‘- Score 2 victory points for each objective you control that is not on Our commentaries are updated regularly; when changes are made, the border of either player’s territories.’ any changes from the previous version will be highlighted in magenta. Where the date has a note, e.g. ‘Revision 2’, this means it Page 36 – The Vice, The Vice has had a local update, only in that language, to clarify a translation Change the second paragraph to: issue or other minor correction. -

The Autonomous Attack Aviation Problem

Air Force Institute of Technology AFIT Scholar Theses and Dissertations Student Graduate Works 3-2021 The Autonomous Attack Aviation Problem John C. Goodwill Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.afit.edu/etd Part of the Aviation Commons, and the Operational Research Commons Recommended Citation Goodwill, John C., "The Autonomous Attack Aviation Problem" (2021). Theses and Dissertations. 4925. https://scholar.afit.edu/etd/4925 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Graduate Works at AFIT Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AFIT Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Autonomous Attack Aviation Problem THESIS John C. Goodwill, MAJ, US Army AFIT-ENS-MS-21-M-162 DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE AIR UNIVERSITY AIR FORCE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE. The views expressed in this document are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the United States Army, the United States Air Force, the United States Department of Defense or the United States Government. This material is declared a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. AFIT-ENS-MS-21-M-162 THE AUTONOMOUS ATTACK AVIATION PROBLEM THESIS Presented to the Faculty Department of Operational Sciences Graduate School of Engineering and Management Air Force Institute of Technology Air University Air Education and Training Command in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Operations Research John C. -

The Death of the Knight

Academic Forum 21 2003-04 The Death of the Knight: Changes in Military Weaponry during the Tudor Period David Schwope, Graduate Assistant, Department of English and Foreign Languages Abstract The Tudor period was a time of great change; not only was the Renaissance a time of new philosophy, literature, and art, but it was a time of technological innovation as well. Henry VII took the throne of England in typical medieval style at Bosworth Field: mounted knights in chivalric combat, much like those depicted in Malory’s just published Le Morte D’Arthur. By the end of Elizabeth’s reign, warfare had become dominated by muskets and cannons. This shift in war tactics was the result of great movements towards the use of projectile weapons, including the longbow, crossbow, and early firearms. Firearms developed in intermittent bursts; each new innovation rendered the previous class of firearm obsolete. The medieval knight was unable to compete with the new technology, and in the course of a century faded into obsolescence, only to live in the hearts, minds, and literature of the people. 131 Academic Forum 21 2003-04 In the history of warfare and other man-vs.-man conflicts, often it has been as much the weaponry of the combatants as the number and tactics of the opposing sides that determined the victor, and in some cases few defeated many solely because of their battlefield armaments. Ages of history are named after technological developments: the Stone Age, Bronze Age, and Iron Age. Our military machine today is comprised of multi-million dollar airplanes that drop million dollar smart bombs and tanks that blast holes in buildings and other tanks with depleted uranium projectiles, but the heart of every modern military force is the individual infantryman with his individual weapon. -

The Best Aircraft for Close Air Support in the Twenty-First Century Maj Kamal J

The Best Aircraft for Close Air Support in the Twenty-First Century Maj Kamal J. Kaaoush, USAF Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed or implied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanction of the Department of Defense, Air Force, Air Education and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US govern- ment. This article may be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. If it is reproduced, the Air and Space Power Journal requests a courtesy line. Introduction and Background n a presentation to a Senate-led defense appropriations hearing, the incumbent Air Force secretary, Deborah Lee James, painted a very grim picture in the face of economic sequestration. “Today’s Air Force is the smallest it’s been since it Iwas established in 1947,” she explained, “at a time when the demand for our Air Force services is absolutely going through the roof.”1 Because of far-reaching govern- mental budget constraints, the Air Force is being forced to make strategic decisions regarding the levels of manning and aircraft to maintain tactical readiness. In 2013 the service responded to a $12 billion budget reduction by cutting nearly 10 percent Fall 2016 | 39 Kaaoush of its inventory of aircraft and 25,000 personnel, necessitating the reduction of flying squadrons and overall combat capability.2 With sequestration scheduled to last until 2023, however, the budget shows no sign of being restored any time soon. Conse- quently, Air Force senior leaders must continue to make tough decisions.3 A number of military experts have proposed eliminating less important “mission sets” by retiring aging airframes and replacing them and their single-role effective- ness with multirole aircraft.4 To meet mounting budget demands, the Air Force chose the A-10 Thunderbolt as the first aircraft to place on the budgetary chopping block.