Here for Life: a Chapter & Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jan. 29, 2020.Pdf

n Ka sas py D p a SALUTE TON a y WHITING, KANSAS H ! Hometown of Larry & Bonnie Eubanks Holton Recorder subscribers for 30 years. CSering te acson County Community or years Volume 153, Issue 8 HOLTON, KANSAS • Wednesday, January 29, 2020 14 Pages $1.00 HOF tickets available Ticket sales for the 15th- annual Holton/Jackson County Chamber of Commerce Hall of Fame banquet — to be held one week from today — have been slow so far, which is not necessarily unusual, according to Cham ber executive director Ashlee York. This year’s community event, honoring Deb Dillner, Diane Gross, Esther Ideker and Floye Knouft — will be held next Wednesday, Feb. 5 at the Evangel United Methodist Church Family Life Center, with a social hour starting at 5:30 p.m. and dinner to be served at 6 p.m. A total of 16 tickets has been re ported sold by Holton’s three banks — Denison State Bank, The Farmers State Bank and GNBank — while about 60 tickets have been sold at the Chamber office, York said this morn ing. However, she added, Chamber officials “always” get tickets sold in the days leading Travis Amon of Holton’s Brahma Excavating operated an excavator to make quick work of a dilapidated house in the 700 block of Pennsylvania up to the annual event. Avenue in Holton yesterday morning. Holton city officials noted that the abandoned, dilapidated house had generated several complaints and had Advance tickets are $30 per been targeted for demolition by the Holton City Commission, which had declared the house a dangerous and unsafe structure last August. -

Anti-Trans Forces Try to Influence Suburban School-Board Election

Robert J. LeFevre Jr., Anna Klimkowicz and Edward M. Yung. Detail from the mailer by Trans United Fund supporting these three pro-trans school board candidates VOL 32, NO. 28 MARCH 29, 2017 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com SCHOOL FIGHT Anti-trans forces try to influence suburban school-board election BY MATT SIMONETTE of a transgender girl who had been denied “Our efforts have been [focused on] access to the girls’ locker room. canvassing on behalf of our candidates in As April 4 general elections loom in suburban Other parents and anti-LGBT advocates District 211 and we’ve been phone-banking Cook and collar county municipalities, few have since decried District 211’s vote in a little bit as well,” said Christensen. “We’ve local school board races will be watched 2015 to accept the government’s deal. been dealing with the Parents4Privacy in more closely than that of Township High Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF), an anti- District 211 for about two years now. They’ve School District 211, in the Northwest suburbs LGBT legal organization, in 2016, filed a made quite a name for themselves, and including Palatine, where board members lawsuit on behalf of aggrieved families. A people now know who they are.” have long been grappling with public local organization called Parents4Privacy She added, “It’s been tough-going, accommodations rules for its transgender has meanwhile become especially active, because we don’t have a lot of volunteers students. recently throwing their support behind and we definitely don’t have a lot of money.” Some local parents formed a coalition school board candidates who would like to About five to 10 canvassers have gone out with both Trans United Fund—a national see the rules rolled back. -

Olivia Bowser Transcript

This transcript was exported on Feb 02, 2021 - view latest version here. John Boccacino: Hello, and welcome back to the 'Cuse Conversations Podcast. My name is John Boccacino, the Communications Specialist in Syracuse University's Office of Alumni Engagement. I'm also a 2003 graduate of the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications with a degree in broadcast journalism. You can find our podcast on all of your major podcasting platforms, including Apple Podcasts, Google Play, and Spotify. You can also find our podcasts at alumni.syr.edu/cuseconversations and anchor.fm/cuseconversations. Olivia Bowser: Mental wellness feels really heavy and your loneliness or your anxiety or your stress is this weight that is just weighing on you. And it doesn't have to feel that way. And that's the whole reason I started Liberate, it's because when you have a community supporting you, and when you are empowered to work through your anxiety and work on yourself, it takes a lot of that heaviness away. John Boccacino: Well, folks, today on the podcast, we have such a timely guest for our alumni audience. Her name is Liv Bowser, and she is going to talk about mental wellbeing, the mental state that we're all dealing with right now. There's so much anxiety, there's so much uncertainty that comes with life in the year 2021, with the pandemic, with the political landscape. And who better to talk about this than someone who is a certified meditation and mindfulness teacher. She graduated with a Marketing Management Degree from Whitman in 2016. -

Liv on Autumn 2018

LIV ON AUTUMN 2018 SPIRIT OF GIVING LIVES ON A BITTERSWEET VISIT THE POWER OF ONE VOICE OLIVIA’S MESSAGE FOR YOU Hello to all you wonderful ONJ Cancer Centre supporters! It gives me so much joy to be able to welcome 2018, especially after the challenging year I had last year with the recurrence of my breast cancer. I’ve been feeling fantastic and was excited to make an extra visit to Melbourne in November to meet with Natalie Morales from the USA Today show and take her on a tour of our amazing ONJ Cancer Centre! Natalie interviewed me (you can see the videos at onjcancercentre.org) and I also had the opportunity to visit patients and their families. I am always touched by the strength and hope of people affected by cancer. I’m excited to let you know of another way you can support us. Have you seen our range of ONJ Cancer Centre merchandise? From tees in micro mesh fabrics and calming candles to shady caps and handy notebooks, there’s something there for everyone! I will be so grateful for your support of this range which helps fund our vital work in cancer research, education, prevention and cancer support services. Go to onjcancercentre.org/shop to explore or visit the new merchandise cabinet on Level 3! To everyone who made a donation, ran an event, participated in the Wellness Walk and Research Run, joined Olivia’s Circle or took action to help in any way in 2017, I salute you and say, thank you! You are all very special souls and I am forever grateful that so many of you care for patients at the ONJ Cancer Centre. -

Pepperdine Welcomes Newton-John

november 2, 2017 The Graphic pepperdine-graphic.com B1B1 LIFE & ARTS Pepperdine welcomes Newton-John Photo Courtesy of Amy Sky Sing it Out | Olivia Newton-John, Amy Sky and Beth Nielson Chapman sing alongside each other on Oct. 26. The trio performed in Smothers Theatre as a part of their LIV ON tour. The LIV ON tour started in October and the trio is set to finish the tour in December this year. “LIV ON” Concert Award-winning singers perform at Pepperdine mary cate long “These girls became my sis- the first time for the women to time.” ing with stuff. And the way to staff writer ters in the making of this CD,” collaborate as a trio. The songs on the album es- deal with it is to find support Newton-John said during the “When I got the call to join sentially were the three artists’ and share your feelings with Smothers Theatre was full of concert. the project, I didn’t even have to way of processing their grief in empathetic and compassionate tearful eyes and sniffly noses as Grief was the initial force blink an eye to say yes,” Chap- a way they hoped would help people.” result of a unique concert ad- that brought the three singers man said during the concert. them personally and encourage The event was cathartic for dressing the issues of bereave- together and spurred collabora- The trio wrote the songs for others. Sky said they hoped the both the singers and listeners. ment and loss. tion. LIV ON in 2015 and 2016. -

BSERVER FILM T H U R S D a Y , NOVEM BER 5, 2015 • Hometownlife.Com ENTERTAINMENT, B10

JAYCEES HOLDING 5K TO HELP VETERANS HAVEN l o c a l n e w s , A 2 BIKING LAKE WAYNE-WESTLAND A GANNETT COMPANY ’ SUPERIOR BECOMES FEATURE BSERVER FILM T H U R S D A Y , NOVEM BER 5, 2015 • hometownlife.com ENTERTAINMENT, B10 H erzberg edges Reeves in council race Godbout, Johnson, Hammons win re-election BY THE NUMBERS WESTLAND LeAnne Rogers assistant, Herzberg will be CITY CLERK Staff Writer joining his first cousin Kevin Coleman, midway through a Four-year term, elect one Three incumbent Westland four-year term, on the council » Richard LeBlanc 5,451; 78% councilmen were re-elected by beginning in January. Jody Rice-White 1,564; 22% voters Thesday while the fourth Former councilman, state incumbent was edged out of a legislator and current Wayne WESTLAND new term. County Commissioner Richard CITY COUNCIL Council President James LeBlanc, D-Westland, was the Four-year term, elect four Godbout, Councilmen B ill John fifth member of the group of » James Godbout (i) 3,912; 15% son and Adam Hammons were candidates campaigning to » Bill Johnson (i) 3,661; 14% the top three vote-getters, earn gether. LeBlanc was elected as » Adam Hammons (i) 3,539; 14% ing four-year council terms. the new Westland city clerk to » Peter Herzberg 3,440; 13% Councilman Dewey Reeves replace Eileen DeHart Schoof, Dewey Reeves (i) 3,333; 13% finished fifth behind challenger who isn’t seeking re-election. Charles Pickering 2,976; 12% Peter Herzberg, who earned a LeBlanc carried 77.5% of the TOM BEAUDOIN Judy McKinney 2,372; 9% two-year council term for a votes cast handily beating Jody Westland school board member Shawna Walker hugs Westland William Campbell 2,339; 9% fourth-place finish. -

Provider and Pharmacy Directory 2020

UCare Medicare Plans HMO-POS Plan Provider and Pharmacy Directory 2020 This directory is current as of 11/17/2020. This directory provides a list of UCare Medicare Plans' current network providers. This directory is for the UCare Medicare Plans' service area that includes all Minnesota counties. To access UCare Medicare Plans' online Provider and Pharmacy Directory, you can visit ucare.org/searchnetwork. For any questions about the information contained in this directory, please call our Customer Service Department at 612-676-3600 or 1-877-523-1515 toll free, 8 am – 8 pm, seven days a week. TTY users should call 612-676-6810 or 1-800-688-2534 toll free. Upon request, we can also give you information in braille, in large print, or other alternate formats if you need it. Y0120__4950_11172020_C Notice of Nondiscrimination UCare complies with applicable Federal civil rights laws and does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability or sex. UCare does not exclude people or treat them differently because of race, color, national origin, age, disability or sex. We provide aids and services at no charge to people with disabilities to communicate effectively with us, such as TTY line, or written information in other formats, such as large print. If you need these services, contact us at 612-676-3200 (voice) or toll free at 1-800-203-7225 (voice), 612-676-6810 (TTY), or 1-800-688-2534 (TTY). We provide language services at no charge to people whose primary language is not English, such as qualified interpreters or information written in other languages. -

Gamma-Ray and Cosmic-Ray Tests of Lorentz Invariance Violation And

Gamma-ray and Cosmic-ray Tests of Lorentz Invariance Violation and Quantum Gravity Models and Their Implications Floyd W. Stecker Astrophysics Science Division, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA Abstract. The topic of Lorentz invariance violation (LIV) is a fundamental question in physics that has taken on particular interest in theoretical explorationsof quantumgravity scenarios. I discuss various γ-ray observations that give limits on predicted potential effects of Lorentz invariance violation. Among these are spectral data from ground based observations of the multi-TeV γ-rays from nearby AGN, INTEGRAL detections of polarized soft γ-rays from the vicinity of the Crab pulsar, Fermi Gamma Ray Space Telescope studies of photon propagation timing from γ-ray bursts, and Auger data on the spectrum of ultrahigh energy cosmic rays. These results can be used to seriously constrain or rule out some models involving Planck scale physics. Possible implications of these limits for quantum gravity and Planck scale physics will be discussed. Keywords: quantum gravity PACS: 04.60Bc INTRODUCTION It has been the major goal of particle physics to discover a theoretical framework for unifying gravity with the other three known forces, viz., electromagnetism, and the weak and strong nuclear forces. Such a theory must be compatible with quantum theory at very small scales corrsponding to very high energies. Even the possibly less ambitious goal of reconciling general relativity with quantum theory has been elusive and may require new concepts to accomplish. There has been a particular interest in the possibility that a quantum gravity theories 3 arXiv:0912.0500v2 [hep-ph] 14 Dec 2009 will lead to Lorentz invariance violation (LIV) at the Planck scale, λPl = Gh¯/c ∼ −35 1.6 × 10 m. -

METRA #940.Pmd

2 Metra Magazine, Issue # 940 METRA MAGAZINE published by Metra Inc., PO BOX 71844 Madison Heights, MI 48071 248.543.3500 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] www.metramagazine.com facebook.com/MaryMetra facebook.com/metramagazine Online since 2003 Published on a month schedule. Established since 1979 publisher / editor • Mari Sappington art director / co-publisher Ken Lamparski Sr. contributing writers • Auntie M Kene Keyz photographers • Danielle Eve, Phil Montoroso, Eric Zuniga, Brono Postigo, Cover & Content Gary Barris, Frank Clark, Photos by Phil Monterosso Jimm “Tuffy” Moner Models: Devin midwest / local sales • M. Sappington Location: Body Zone national advertising • Rivendell Media 212.242.6863 FRIENDS OF DOROTHY...8 distributors • UPS & Jim Noble WHO’S DOIN’ WHAT, webmaster • Wolfmarkadwerks WHEN AND WHERE Publication of the name or photograph of any person or IN METRALAND! organization in articles in METRA MAGAZINE is not to be construed as an indication of the sexual orientation of such person or organization. All copy text, display photos Compiled By Auntie M. and illustrations in advertising are published with the understanding that the advertisers are fully authorized, have secured proper consents (written, verbal, e-mail etc) for the use of names, pictures or testimonials of any living person(s) and METRA MAGAZINE may lawfully OUT FLASHIN’...9 publish and cause such publication to be made and advertiser automatically agrees to by submitting said ad and to indemnify and save blameless the publisher from any and all liability loss and expense of any nature of such publication. Nothing appearing in METRA MAGAZINE may be reprinted either wholly or in part ISSUE #940 Jan., 29th - Feb., 19th 2020 without written permission/e-mail from the publishers. -

The Seasons Come and Go

Jar.jaty/Febnjary, 2006. `1! 1/ The seasons come and go. PROFIT OF Loss? "For what will it profit a man if he gaitis the whole world, and Oh, that he might own this great treasure he had found! loses his owii soul?"-M ark 8:36 Some would argue that Jesus was overdrawing the picture, that God would never require this much. And besides, they he experienced business owner knows the importance of say, Jesus paid the price, so we can keep what we wish and watching the bottom line. If critical attention is not given to have the treasure of great price, too! profit and loss tracking, profits will suffer and the business Before drawing conclusions, let us consider the profit and will ultimately fail. Before making a purchase, conscientious loss. The question of profit and loss, of risk and reward, owners look carefully at the risks. applies to every aspect of life. We need to constantly ask our Yet, when it comes to the profitability of our lives, this sim selves whether the things we are seeking are worth what we ple rule is often ignored. Perhaps this is due in part to a dis are giving up in exchange. Everything has cost. Is having my torted values system. In our culture we tend to think of own way worth the cost in time, money, leisure, or freedom? personal profit in terms of money, pleasure, and things-our Eternal salvation is free-the reward is too great for us to job title, our salar' our bank account, our clothes, the model even begin to purchase it. -

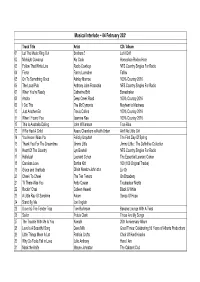

04 02 2021 Playlist

Musical Interlude ~ 04 February 2021 Track Title Artist CD / Album 01 Let The Music Ring Out Brothers 3 Let it Drift 02 Midnight Cowboys Aly Cook Horseshoe Rodeo Hotel 03 Follow That White Line Radio Cowboys NFS Country Singles For Radio 04 Fierce Fanny Lumsden Fallow 05 On To Something Good Ashley Monroe 100% Country 2016 06 The Local Pub Anthony John Fraccchia NFS Country Singles For Radio 07 When You're Ready Catherine Britt Boneshaker 08 Anchor Deep Creek Road 100% Country 2016 09 I Got This The McClymonts Mayhem to Madness 10 Just Another Girl Travis Collins 100% Country 2016 11 When I Found You Jasmine Rae 100% Country 2016 12 This Is Australia Calling John Williamson True Blue 13 If We Had A Child Kasey Chambers w/Keith Urban Ain't No Little Girl 14 You Know I Miss You Felicity Urquhart The First Day Of Spring 15 Thank You For The Dreamtime Jimmy Little Jimmy Little : The Definitive Collection 16 Heart Of The Country Lyn Bowtell NFS Country Singles For Radio 17 Hallelujah Leonard Cohen The Essential Leonard Cohen 18 Careless Love Eartha Kitt 100 (100 Original Tracks) 19 Grace and Gratitude Olivia Newton-John et al Liv On 20 Cheek To Cheek The Ten Tenors On Broadway 21 Til There Was You Andy Cowan Troubadour Nights 22 Rockin' Chair Colleen Hewett Black & White 23 A Little Ray Of Sunshine Axiom Songs Of Hope 24 Stand By Me Jon English 25 (Love Is) The Tender Trap Tom Burlinson Banana Lounge With A Twist 26 Sailor Petula Clark These Are My Songs 27 The Trouble With Me Is You Kamahl 20th Anniversary Album 28 Love Is A Beautiful Song Dave Mills Good Times: Celebrating 50 Years of Alberts Productions 29 Little Things Mean A Lot Patricia Crofts Choir Of Hard Knocks 30 Why Do Fools Fall in Love Julie Anthony Here I Am 31 Mack the Knife Wayne Johnston The Cabaret Club. -

ивð¸ÑÐÑžñ‚Ñšð½-Джоð½ Ðлбуð¼ ÑпиÑ

ÐžÐ»Ð¸Ð²Ð¸Ñ ÐÑ ŽÑ‚ън-Джон ÐÐ »Ð±ÑƒÐ¼ ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (диÑÐ ºÐ¾Ð³Ñ€Ð°Ñ„иÑÑ ‚а & график) Back to Basics – The Essential https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/back-to-basics-%E2%80%93-the-essential- Collection 1971–1992 collection-1971%E2%80%931992-302260/songs Totally Hot https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/totally-hot-1323228/songs Long Live Love https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/long-live-love-753724/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/gaia%3A-one-woman%27s-journey- Gaia: One Woman's Journey 1007315/songs Have You Never Been Mellow https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/have-you-never-been-mellow-945782/songs Making a Good Thing Better https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/making-a-good-thing-better-956764/songs Don't Stop Believin' https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/don%27t-stop-believin%27-908512/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/if-you-love-me%2C-let-me-know- If You Love Me, Let Me Know 1095933/songs Olivia https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/olivia-1224300/songs Clearly Love https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/clearly-love-867909/songs Grace and Gratitude https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/grace-and-gratitude-661371/songs Stronger Than Before https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/stronger-than-before-928100/songs Liv On https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/liv-on-27536529/songs Two of a Kind https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/two-of-a-kind-17058348/songs A Few Best Men https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/a-few-best-men-4656715/songs