Revisiting the Iconic: the Excavation of the Reelfitz Pit Engine and the Newcomen Steam Engine in Cumberland, UK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Five Year Housing Land Supply As of 31 March 2019

Five Year Housing Land Supply as of 31st March 2019 1.0 Housing Requirement 1.1 Due to the under delivery of houses in Allerdale (for the areas outside the Lake District National Park Authority) (see Table 1), the Council considers it prudent that a 5% buffer is applied to the annual housing target, consistent with the Housing Delivery Test. The shortfall of dwellings will be addressed in the short term and therefore this buffer has been added to the five year land supply target in full, as per the Sedgefield method. Monitoring Period Net completions Local Plan Target Cumulative shortfall 2011/2012 201 304 -103 2012/2013 189 304 -218 2013/2014 196 304 -326 2014/2015 300 304 -330 2015/2016 385 304 -249 2016/2017 250 304 -303 2017/2018 480 304 -127 2018/2019 337 304 -94 Total 2,338 2,432 -94 Table 1: Net housing completions since 1st April 2011 1.2 Therefore the annual housing requirement for the next 5 years is 339 dwellings per annum (see Table 2). Housing target April 2018-March 2023 1,520 (304 x 5) Housing Shortfall (1st April 2011 – 1st April 2018) -94 Housing Requirement April 2011-March 2024 (5% buffer 1,695 applied to target and shortfall) Annualised Housing Requirement (1695/5) 339 Table 2: Calculating the annual housing requirement 2.0 Housing Supply 2.1 Allerdale Borough Council’s housing supply has been calculated with the following categories (Table 3): • Large sites with planning permission (10 dwellings or more) (see Appendix A) • Small sites with planning permission (9 dwellings or less) (see Appendix B) • Sites with resolution to grant planning permission subject to a s106 Agreement being signed (see Appendix C) 2.2 Appendix D includes details of sites which support windfall allowance of 30 dwellings per annum. -

Have Your Say Workington Cycling and Walking Consultation

Workington Cycling and Walking Have your say Consultation Public Consultation from: 14 July to 6 August 2021 For more details and links to the questionnaire please visit: cumbria.gov.uk/ cyclingandwalking 40% of people in the Workington area travel less than 5km to work, compared to the national average of 35%. 21% of people in the Workington area travel less than 2km to work, compared to the national average of 17%. 2% of people in the Workington area cycle to work, compared to the national average of 3%. 19% of people in the Workington area walk to work, compared to the national average of 11%. 73% of the internal trips in the Workington area are made by car. 30% of children in the Allerdale District walk to school compared to the County average of 35% 1% of children in the Allerdale District cycle to school compared to the County average of 2% Workington Cycling and Walking Consultation Summary We are holding a consultation on proposals to improve the cycling and walking network in Workington and the surrounding area, to promote more active travel and to make everyone feel confident they can walk or cycle. The consultation focusses on shorter urban journeys in Workington, but we also welcome feedback on journeys to and from surrounding communities. Details of the proposed routes are included in this consultation document. We want you to provide feedback on these proposals so we can develop the best possible Local Cycling and Walking Infrastructure Plan for Workington. Please take the time to get involved, read this consultation document and provide your feedback. -

Cumbrian Railway Ancestors B Surnames Surname First Names

Cumbrian Railway Ancestors B surnames Year Age Surname First names Employment Location Company Date Notes entered entered Source service service Babbs John Porter Barrow Goods FUR 08/08/1895 Entered service on 20/- pw 1895 26 FR Staff Register Babbs John Parcels Porter Barrow Central FUR 25/06/1900 From Barrow Goods on 22/- pw 1895 26 FR Staff Register Babbs John Labourer Buccleuch Jct to Goods Dep FUR 16/09/1907 Entered service 1907 38 Furness PW staff register p 6 Babbs John P.Way Askam FUR 00/03/1908 AMB Listed as available mobilisation for Babbs John P Way Labourer Askam FUR 06/08/1914 RAIL 214/81 entrenchmen works Babe William Signalman Carlisle MID 14/11/1876 New appointment. Still in post in 1898 RAIL 491/1024 Babe William Signalman Carlisle MID 00/00/1902 Died RAIL 491/1026 Backhouse James Porter Barrow ? FUR 00/00/1851 Age 32 b.Whitehall Census Backhouse Luke Clerk Askam FUR 10/10/1881 Entered service on 5/6 pw 1881 15 FR Staff Register Transferred from Askam Iron Works on Backhouse Luke Office Boy Dalton FUR 15/05/1882 1881 15 FR Staff Register 7/6 pw Backhouse Luke Clerk Foxfield FUR 20/02/1883 Transferred from Dalton on 10/- pw 1881 15 FR Staff Register Backhouse Luke Clerk Ulverston FUR 29/10/1883 Transferred from Foxfield on 12/6 pw 1880 15 FR Staff Register Backhouse Luke Clerk Ulverston FUR 08/05/1886 Resigned 1880 15 FR Staff Register Backhouse R Underman Lake Side LMS 05/05/1928 In service with LMS on May 5 1928 Furness PW staff register p 26,25 Bacon A. -

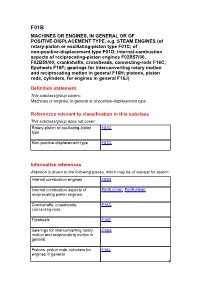

MACHINES OR ENGINES, in GENERAL OR of POSITIVE-DISPLACEMENT TYPE, Eg STEAM ENGINES

F01B MACHINES OR ENGINES, IN GENERAL OR OF POSITIVE-DISPLACEMENT TYPE, e.g. STEAM ENGINES (of rotary-piston or oscillating-piston type F01C; of non-positive-displacement type F01D; internal-combustion aspects of reciprocating-piston engines F02B57/00, F02B59/00; crankshafts, crossheads, connecting-rods F16C; flywheels F16F; gearings for interconverting rotary motion and reciprocating motion in general F16H; pistons, piston rods, cylinders, for engines in general F16J) Definition statement This subclass/group covers: Machines or engines, in general or of positive-displacement type References relevant to classification in this subclass This subclass/group does not cover: Rotary-piston or oscillating-piston F01C type Non-positive-displacement type F01D Informative references Attention is drawn to the following places, which may be of interest for search: Internal combustion engines F02B Internal combustion aspects of F02B 57/00; F02B 59/00 reciprocating piston engines Crankshafts, crossheads, F16C connecting-rods Flywheels F16F Gearings for interconverting rotary F16H motion and reciprocating motion in general Pistons, piston rods, cylinders for F16J engines in general 1 Cyclically operating valves for F01L machines or engines Lubrication of machines or engines in F01M general Steam engine plants F01K Glossary of terms In this subclass/group, the following terms (or expressions) are used with the meaning indicated: In patent documents the following abbreviations are often used: Engine a device for continuously converting fluid energy into mechanical power, Thus, this term includes, for example, steam piston engines or steam turbines, per se, or internal-combustion piston engines, but it excludes single-stroke devices. Machine a device which could equally be an engine and a pump, and not a device which is restricted to an engine or one which is restricted to a pump. -

Takeaway & Delivery

01900 Takeaway and Delivery Menu Open 7 days a week Takeaway Workington Seaton Maryport Broughton Moor Little Broughton Dearham Little Clifton Harrington High Harrington Distington Clifton Flimby £2.50 £2.50 £3.50 £3.50 £3.50 £3.50 £3.50 £2.50 £2.50 £3.50 £2.50 £2.50 KEBABS BURGERS CASPIAN DISHES SUNDRIES Served in pitta bread with salad Served in buns with garnish and fries Zaffron Chicken £7.00 Plain Jacket Potato £3.20 and choice of garlic or chilli sauce 1⁄4lb 1⁄2lb Breast of chicken in saffron sauce Add a filling for 70p Doner Kebab (Caspian’s Own Special Recipe) £6.00 Beefburger £3.70 £4.40 served with chips, jacket potato or rice Cheeseburger £4.00 £4.70 Choose from Prawns, Tuna, Cheese or Coleslaw Kofteh Kebab £6.60 Spaghetti Carbonara £8.00 Garlic Burger £4.00 £4.70 Smoked bacon in a creamy white sauce Mixed Salad £2.20 Chicken Kebab £6.60 Chilli Burger £4.00 £4.70 Hawaiian Burger £4.50 £5.20 Scampi & Chips £7.00 Prawn Salad with Marie Rose Sauce £3.00 Steak Kebab £6.60 Beefburger with pineapple ring Finest quality scampi served Tuna Salad £3.00 American Cheeseburger £4.50 £5.20 with tartare sauce Mixed Kebab (Steak, Chicken & Doner) £6.60 Beefburger with bacon & cheese Ham Salad £3.00 TAKEAWAY & DELIVERY Standard Spaghetti Bolognese £7.00 63397 House Special Kebab £7.70 Feta Cheese Salad £2.70 DERWENT DRIVE • DERWENT HOWE ESTATE • WORKINGTON (Steak, Chicken, Kofte & Doner) Chickenburger £4.40 Lasagne £8.80 Garlic Chickenburger £4.50 With fries Chicken Salad £3.00 OPENING HOURS Chicken Nuggets £4.10 Feta Cheese Slice £1.10 Monday, -

Assessing Steam Locomotive Dynamics and Running Safety by Computer Simulation

TRANSPORT PROBLEMS 2015 PROBLEMY TRANSPORTU Volume 10 Special Edition steam locomotive; balancing; reciprocating; hammer blow; rolling stock and track interaction Dāvis BUŠS Institute of Transportation, Riga Technical University Indriķa iela 8a, Rīga, LV-1004, Latvia Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] ASSESSING STEAM LOCOMOTIVE DYNAMICS AND RUNNING SAFETY BY COMPUTER SIMULATION Summary. Steam locomotives are preserved on heritage railways and also occasionally used on mainline heritage trips, but since they are only partially balanced reciprocating piston engines, damage is made to the railway track by dynamic impact, also known as hammer blow. While causing a faster deterioration to the track on heritage railways, the steam locomotive may also cause deterioration to busy mainline tracks or tracks used by high speed trains. This raises the question whether heritage operations on mainline can be done safely and without influencing the operation of the railways. If the details of the dynamic interaction of the steam locomotive's components are examined with computerised calculations they show differences with the previous theories as the smaller components cannot be disregarded in some vibration modes. A particular narrow gauge steam locomotive Gr-319 was analyzed and it was found, that the locomotive exhibits large dynamic forces on the track, much larger than those given by design data, and the safety of the ride is impaired. Large unbalanced vibrations were found, affecting not only the fatigue resistance of the locomotive, but also influencing the crew and passengers in the train consist. Developed model and simulations were used to check several possible parameter variations of the locomotive, but the problems were found to be in the original design such that no serious improvements can be done in the space available for the running gear and therefore the running speed of the locomotive should be limited to reduce its impact upon the track. -

![[Thesis Title Goes Here]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3925/thesis-title-goes-here-423925.webp)

[Thesis Title Goes Here]

DETAILED STUDY OF THE TRANSIENT ROD PNEUMATIC SYSTEM ON THE ANNULAR CORE RESEARCH REACTOR A Thesis Presented to The Academic Faculty by Brandon M. Fehr In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Nuclear Engineering in the School of Nuclear and Radiological Engineering and Medical Physics Program, George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology May 2016 COPYRIGHT © 2016 BY BRANDON M. FEHR iv DETAILED STUDY OF THE TRANSIENT ROD PNEUMATIC SYSTEM ON THE ANNULAR CORE RESEARCH REACTOR Approved by: Dr. Farzad Rahnema, Advisor Mr. Michael Black School of Nuclear and Radiological R&D S&E Mechanical Engineering Engineering Sandia National Laboratories Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Tristan Utschig School of Nuclear and Radiological Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Bojan Petrovic School of Nuclear and Radiological Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology Date Approved: April 11, 2016 v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to give the utmost appreciation to my colleagues at Sandia National Laboratories for their support, with special thanks to Michael Black, James Arnold, and Paul Helmick for their technical guidance. I would also like to thank Dulce Barrera and Elliott Pelfrey for their encouragement and support, and Bennett Lee for his help with proofreading and formatting. Special thanks to Dr. Farzad Rahnema for his guidance and contract support, as well as, Dr. Bojan Petrovic and Dr. Tris Utschig for serving on my committee. Lastly, I would like to thank my parents for their support and encouragement during the whole journey. This research was funded by Weapons Science & Technology (WS&T), Readiness in Technical Base and Facilities (RTBF). -

Early Christian' Archaeology of Cumbria

Durham E-Theses A reassessment of the early Christian' archaeology of Cumbria O'Sullivan, Deirdre M. How to cite: O'Sullivan, Deirdre M. (1980) A reassessment of the early Christian' archaeology of Cumbria, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7869/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Deirdre M. O'Sullivan A reassessment of the Early Christian.' Archaeology of Cumbria ABSTRACT This thesis consists of a survey of events and materia culture in Cumbria for the period-between the withdrawal of Roman troops from Britain circa AD ^10, and the Viking settlement in Cumbria in the tenth century. An attempt has been made to view the archaeological data within the broad framework provided by environmental, historical and onomastic studies. Chapters 1-3 assess the current state of knowledge in these fields in Cumbria, and provide an introduction to the archaeological evidence, presented and discussed in Chapters ^--8, and set out in Appendices 5-10. -

Social Diary Workington

Activities and Social Groups in the Workington Area ‘Part of the Cumbria Health and Social Wellbeing System’ supported by Cumbria County Council This social diary provides information on opportunities in the local community and on a wide range of services. It is listed by days activities. Arts and Crafts Clubs: Art Class Lamplugh Village Hall, Lamplugh, weekly Thursdays 3.00-5.30pm, Water colour and Drawing classes for all abilities, NEED TO BOOK. Contact Sandra Cooper: 01946 861416 Art Class Harrington Youth Club, Church Road, weekly Thursdays 10.00am- 12.00pm (term-time only). Contact Sheila Fielder: 01946 831199 or [email protected] Art Class Distington Community Centre, Church Road, Distington, weekly Tuesdays 6.15-8.15pm. Contact the centre: 01946 834297 Craft and Chat The Oval Centre, Salterbeck. Everyone is welcome. Every Friday 11am –3:00pm. For more information contact Oval Centre: 01946 834713 Craft Club Distington Community Centre, Church Road, Distington, weekly Tuesdays 1.00-3.00pm. Contact: Distington Community Centre: 01946 834297 Crafty Corner Moorclose Library, Moorclose campus, Needham Drive, Workington, fortnightly alternate Tuesdays 2.00-4.00pm. Contact the Library: 01900 602736 Craft Night Knitting, crochet, Helena Thompson Museum, Park End Road, Workington, monthly 1st Thursday of month 7.00-9.00pm, £3. Contact the Museum: 01900 64040 Embroidery Helena Thompson Museum, Park End Road, Workington, weekly Mondays 10.00am - 3.00pm. Contact The museum: 01900 64040 Knit & Natter Moorclose Community Centre, Workington, weekly Monday 1.00- 3.00pm, Social and crafts. Contact the Centre: 01900 871789 Knit & Natter Distington Community Centre, Church Road, Distington, weekly Fridays 1.00-3.00pm. -

I Lecture Note

Machine Dynamics – I Lecture Note By Er. Debasish Tripathy ( Assist. Prof. Mechanical Engineering Department, VSSUT, Burla, Orissa,India) Syllabus: Module – I 1. Mechanisms: Basic Kinematic concepts & definitions, mechanisms, link, kinematic pair, degrees of freedom, kinematic chain, degrees of freedom for plane mechanism, Gruebler’s equation, inversion of mechanism, four bar chain & their inversions, single slider crank chain, double slider crank chain & their inversion.(8) Module – II 2. Kinematics analysis: Determination of velocity using graphical and analytical techniques, instantaneous center method, relative velocity method, Kennedy theorem, velocity in four bar mechanism, slider crank mechanism, acceleration diagram for a slider crank mechanism, Klein’s construction method, rubbing velocity at pin joint, coriolli’s component of acceleration & it’s applications. (12) Module – III 3. Inertia force in reciprocating parts: Velocity & acceleration of connecting rod by analytical method, piston effort, force acting along connecting rod, crank effort, turning moment on crank shaft, dynamically equivalent system, compound pendulum, correction couple, friction, pivot & collar friction, friction circle, friction axis. (6) 4. Friction clutches: Transmission of power by single plate, multiple & cone clutches, belt drive, initial tension, Effect of centrifugal tension on power transmission, maximum power transmission(4). Module – IV 5. Brakes & Dynamometers: Classification of brakes, analysis of simple block, band & internal expanding shoe brakes, braking of a vehicle, absorbing & transmission dynamometers, prony brakes, rope brakes, band brake dynamometer, belt transmission dynamometer & torsion dynamometer.(7) 6. Gear trains: Simple trains, compound trains, reverted train & epicyclic train. (3) Text Book: Theory of machines, by S.S Ratan, THM Mechanism and Machines Mechanism: If a number of bodies are assembled in such a way that the motion of one causes constrained and predictable motion to the others, it is known as a mechanism. -

WSA Engineering Branch Training 3

59 RECIPROCATING STEAM ENGINES Reciprocating type main engines have been used to propel This is accomplished by the guide and slipper shown in the ships, since Robert Fulton first installed one in the Clermont in drawing. 1810. The Clermont's engine was a small single cylinder affair which turned paddle wheels on the side of the ship. The boiler was only able to supply steam to the engine at a few pounds pressure. Since that time the reciprocating engine has been gradually developed into a much larger and more powerful engine of several cylinders, some having been built as large as 12,000 horsepower. Turbine type main engines being much smaller and more powerful were rapidly replacing reciprocating engines, when the present emergency made it necessary to return to the installation of reciprocating engines in a large portion of the new ships due to the great demand for turbines. It is one of the most durable and reliable type engines, providing it has proper care and lubrication. Its principle of operation consists essentially of a cylinder in which a close fitting piston is pushed back and forth or up and down according to the position of the cylinder. If steam is admitted to the top of the cylinder, it will expand and push the piston ahead of it to the bottom. Then if steam is admitted to the bottom of the cylinder it will push the piston back up. This continual back and forth movement of the piston is called reciprocating motion, hence the name, reciprocating engine. To turn the propeller the motion must be changed to a rotary one. -

Nepgill, Bridgefoot, Workington, Cumbria

Nepgill, Bridgefoot, Workington, Cumbria £59,959 Nepgill, Bridgefoot, Workington, service to both towns where a range of shops, schools and amenities can be found. Cumbria OUR VIEW £59,959 This spacious two double bedroom park home benefits from LPG central heating and double glazing. The property is located on a corner plot and is accessed via a block paved DESCRIPTION path to the front door that opens into the lounge/dining room EPC EXEMPT. A well presented two double bedroom park having a coal effect electric fire set in a feature surround home benefiting from LPG central heating and double glazing. with a marble effect backing and hearth plus wood effect The accommodation briefly comprises of lounge/dining room, laminate flooring. From the lounge there is a door into a kitchen, two double bedrooms, bathroom and gardens. hallway which gives access to the other rooms. The kitchen has been fitted with a range of modern wall and base units DIRECTIONS with contrasting work-surfaces incorporating a sink unit, built Head out of Workington on the A66 towards Cockermouth, in eye-level electric oven and gas hob with chimney style when you get to the Stainburn roundabout take the second extractor fan over, plumbing for washing machine, an integral exit and go up the bypass. When you get to the next wine rack and tiled effect laminate flooring. There are two roundabout take the last exit signposted Whitehaven and then double bedrooms, the master having built in wardrobes and turn immediately left into the village of Bridgefoot. Follow this built in bedside cabinets.