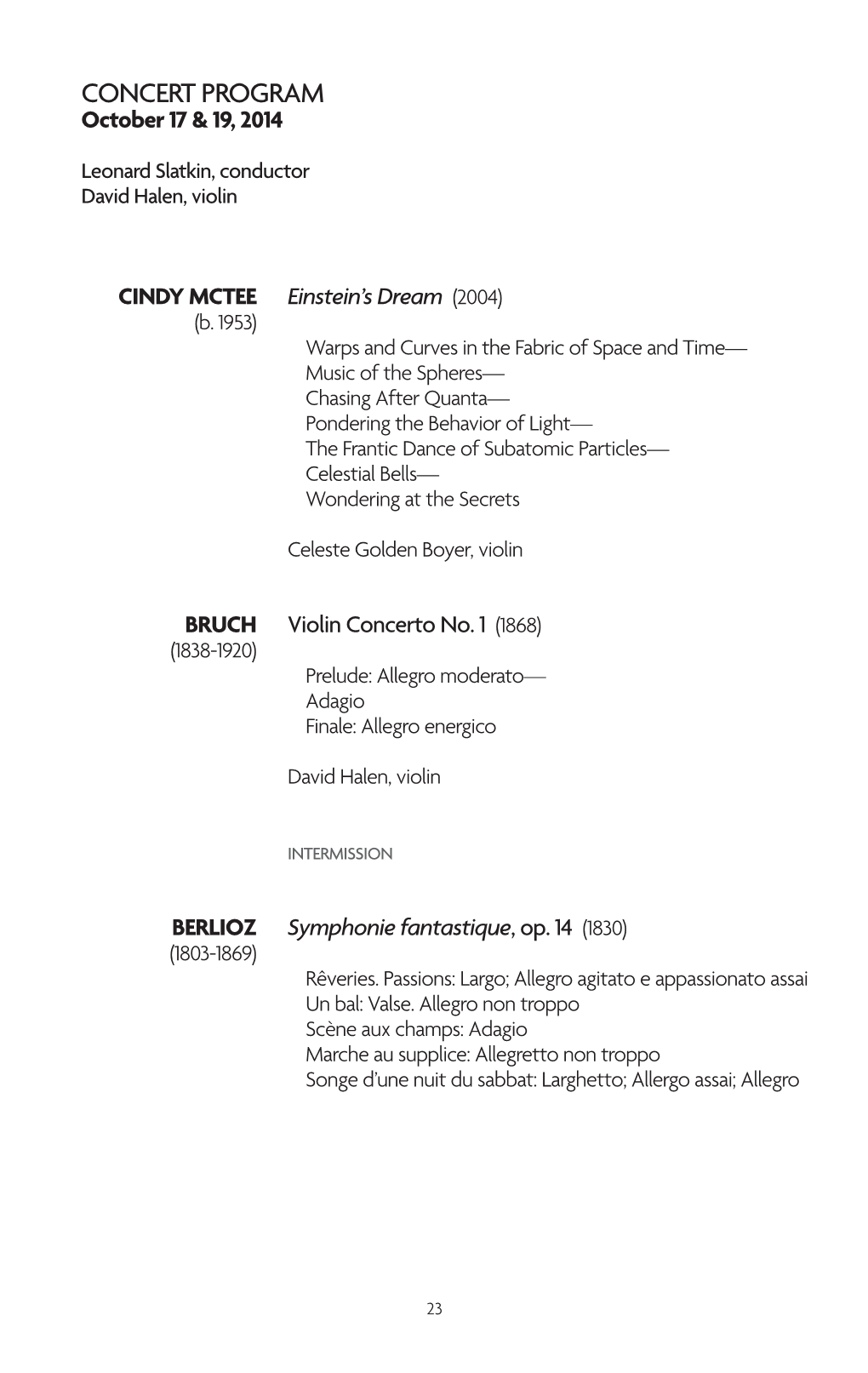

Symphonie Fantastique, Op

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2015–2016

ANNUAL REPORT 2015–2016 NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC 2015–16 ANNUAL REPORT 1 CONTENTS Reflections on the 2015–16 Season 2 Oscar S. Schafer, Chairman 4 Matthew VanBesien, President 6 Alan Gilbert, Music Director 8 Year at a Glance 10 Our Audiences 12 The Orchestra 14 The Board of Directors 20 The Administration 22 Conductors, Soloists, and Ensembles 24 Serving the Community 26 Education 28 Expanding Access 32 Global Immersion 36 Innovation and Preservation 40 At Home and Online 42 Social Media 44 The Archives 47 The Year in Pictures 48 The Benefactors 84 Lifetime Gifts 86 Leonard Bernstein Circle 88 Annual Fund 90 Education Donors 104 Heritage Society 106 Volunteer Council 108 Independent Auditor’s Report 110 2 NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC 2015–16 ANNUAL REPORT THE SEASON AT A GLANCE Second Line Title Case Reflections on the 2015–16 Season 2 NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC 2015–16 ANNUAL REPORT NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC 2015–16 ANNUAL REPORT 3 REFLECTIONS ON THE 2015–16 SEASON From the New York Philharmonic’s Leadership I look back on the Philharmonic’s 2015–16 season and remember countless marvelous concerts that our audiences loved, with repertoire ranging from the glory of the Baroque to the excitement of the second NY PHIL BIENNIAL. As our Music Director, Alan Gilbert has once again brought excitement and inspiration to music lovers across New York City and the world. I also look back on the crucial, impactful developments that took place offstage. Throughout the season our collaboration with Lincoln Center laid a strong foundation for the renovation of our home. -

From the Violin Studio of Sergiu Schwartz

CoNSERVATORY oF Music presents The Violin Studio of Sergiu Schwartz SPOTLIGHT ON YOUNG VIOLIN VIRTUOSI with Tao Lin, piano Saturday, April 3, 2004 7:30p.m. Amamick-Goldstein Concert Hall de Hoernle International Center Program Polonaise No. 1 in D Major ..................................................... Henryk Wieniawski Gabrielle Fink, junior (United States) (1835 - 1880) Tambourin Chino is ...................................................................... Fritz Kreisler Anne Chicheportiche, professional studies (France) (1875- 1962) La Campanella ............................................................................ Niccolo Paganini Andrei Bacu, senior (Romania) (1782-1840) (edited Fritz Kreisler) Romanza Andaluza ....... .. ............... .. ......................................... Pablo de Sarasate Marcoantonio Real-d' Arbelles, sophomore (United States) (1844-1908) 1 Dance of the Goblins .................................................................... Antonio Bazzini Marta Murvai, senior (Romania) (1818- 1897) Caprice Viennois ... .... ........................................................................ Fritz Kreisler Danut Muresan, senior (Romania) (1875- 1962) Finale from Violin Concerto No. 1 in g minor, Op. 26 ......................... Max Bruch Gareth Johnson, sophomore (United States) (1838- 1920) INTERMISSION 1Ko<F11m'1-za from Violin Concerto No. 2 in d minor .................... Henryk Wieniawski ten a Ilieva, freshman (Bulgaria) (1835- 1880) llegro a Ia Zingara from Violin Concerto No. 2 in d minor -

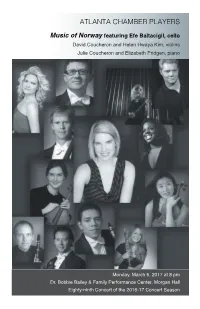

Atlanta Chamber Players, "Music of Norway"

ATLANTA CHAMBER PLAYERS Music of Norway featuring Efe Baltacigil, cello David Coucheron and Helen Hwaya Kim, violins Julie Coucheron and Elizabeth Pridgen, piano Monday, March 6, 2017 at 8 pm Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center, Morgan Hall Eighty-ninth Concert of the 2016-17 Concert Season program JOHAN HALVORSEN (1864-1935) Concert Caprice on Norwegian Melodies David Coucheron and Helen Hwaya Kim, violins EDVARD GRIEG (1843-1907) Andante con moto in C minor for Piano Trio David Coucheron, violin Efe Baltacigil, cello Julie Coucheron, piano EDVARD GRIEG Violin Sonata No. 3 in C minor, Op. 45 Allegro molto ed appassionato Allegretto espressivo alla Romanza Allegro animato - Prestissimo David Coucheron, violin Julie Coucheron, piano INTERMISSION JOHAN HALVORSEN Passacaglia for Violin and Cello (after Handel) David Coucheron, violin Efe Baltacigil, cello EDVARD GRIEG Cello Sonata in A minor, Op. 36 Allegro agitato Andante molto tranquillo Allegro Efe Baltacigil, cello Elizabeth Pridgen, piano featured musician FE BALTACIGIL, Principal Cello of the Seattle Symphony since 2011, was previously Associate Principal Cello of The Philadelphia Orchestra. EThis season highlights include Brahms' Double Concerto with the Oslo Radio Symphony and Vivaldi's Double Concerto with the Seattle Symphony. Recent highlights include his Berlin Philharmonic debut under Sir Simon Rattle, performing Bottesini’s Duo Concertante with his brother Fora; performances of Tchaikovsky’s Variations on a Rococo Theme with the Bilkent & Seattle Symphonies; and Brahms’ Double Concerto with violinist Juliette Kang and the Curtis Symphony Orchestra. Baltacıgil performed a Brahms' Sextet with Itzhak Perlman, Midori, Yo-Yo Ma, Pinchas Zukerman and Jessica Thompson at Carnegie Hall, and has participated in Yo-Yo Ma’s Silk Road Project. -

January 07, 2018

January 07, 2018: (Full-page version) Close Window “Bores can be divided into two classes; those who have their own particular subject, and those who do not need a subject.” — A. A. Milne Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, 00:01 Buy Now! Poulenc Sextet for piano and winds Roge/Gallois/Bourgue/Portal/Wallez/Cazalet London 421 581 028942158122 Awake! 00:20 Buy Now! Tchaikovsky Elegie ~ Serenade for Strings in C, Op. 48 Moscow Virtuosi/Spivakov RCA 61964 090266196425 00:31 Buy Now! Borodin String Quartet No. 2 in D Emerson String Quartet DG 445 551 028944555127 01:00 Buy Now! Fauré Pavane, Op. 50 Philadelphia Orchestra/Ormandy Sony Classical 62644 074646264423 01:08 Buy Now! Schubert Symphony No. 6 in C, D. 589 Cologne Radio Symphony/Wand EMI 47875 077774787529 01:42 Buy Now! Wagner Prelude to Act 1 & Love-Death ~ Tristan & Isolde NY Philhamonic/Boulez Sony 64108 074646410820 Andante and Rondo for 2 Flutes and Piano, Op. 01:59 Buy Now! Doppler Rampal/Arimany/Ritter Delos 3212 013491321226 25 02:09 Buy Now! Bach I call to Thee, Lord Jesus Christ, BWV 639 Ma/Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra/Koopman Sony 60680 074646068021 02:13 Buy Now! Beethoven Symphony No. 6 in F, Op. 68 "Pastoral" Philharmonia Orchestra/Ashkenazy Decca 410 003 028941000323 03:01 Buy Now! Haydn Horn Concerto No. 1 in D Baumann/Academy SMF/Brown Philips 422 346 028942234628 03:18 Buy Now! Rossini Overture ~ William Tell Vienna Philharmonic/Sargent Seraphim/EMI 69137 724356913721 03:32 Buy Now! Mendelssohn String Quartet in A minor, Op. -

Taking Flight Beginning with a Tribute to Lindbergh, the St

TAKING FLIGHT BEGINNING WITH A TRIBUTE TO LINDBERGH, THE ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY EXPRESSES THE SPIRIT OF ST. LOUIS. BY EDDIE SILVA DILIP VISHWANAT David Robertson Begin with a new beginning. The St. Louis Symphony’s 2016-17 season, its 137th, starts with the turn of a propeller, a steep rise into uncluttered skies, and a lonely, perilous journey that changed how people lived, thought, and dreamed. Charles Lindbergh’s silvery craft was christened The Spirit of St. Louis, and pilot and aircraft made their historic flight together across the Atlantic 90 years ago. The name “Spirit of St. Louis” also reflects upon the daring and innovation of a few St. Louisans early in the 20th century. It also speaks to St. Louis now, near the beginning of a new century amidst a whirlwind of innovation that turns more swiftly than a propeller. The St. Louis Symphony, Music Director David Robertson has remarked often, embodies that spirit: innovative, daring, risk-taking, enduring, agile, resourceful—give it an engine and a pair of wings and you’ll see Paris by morning. Kurt Weill’s The Flight of Lindbergh opens the 2016-17 season (September 16-17). Described as a “radio cantata,” it is one of the early collaborations between Weill and Bertolt Brecht, who created the classic The Threepenny Opera as well as other distinctive Brecht/Weill productions. KMOX’s Charlie Brennan provides the radio expertise as narrator of The Flight of Lindbergh. This 1929 work, written in the flush of inspiration that followed Lindbergh’s 6 Taking Flight achievement, will feel fresh, new, and innovative in 2016. -

95.3 Fm 95.3 Fm

October/NovemberMarch/April 2013 2017 VolumeVolume 41, 46, No. No. 3 1 !"#$%&'95.3 FM Brahms: String Sextet No. 2 in G, Op. 36; Marlboro Ensemble Saeverud: Symphony No. 9, Op. 45; Dreier, Royal Philharmonic WHRB Orchestra (Norwegian Composers) Mozart: Clarinet Quintet in A, K. 581; Klöcker, Leopold Quartet 95.3 FM Gombert: Missa Tempore paschali; Brown, Henry’s Eight Nielsen: Serenata in vano for Clarinet,Bassoon,Horn, Cello, and October-November, 2017 Double Bass; Brynildsen, Hannevold, Olsen, Guenther, Eide Pokorny: Concerto for Two Horns, Strings, and Two Flutes in F; Baumann, Kohler, Schröder, Concerto Amsterdam (Acanta) Barrios-Mangoré: Cueca, Aire de Zamba, Aconquija, Maxixa, Sunday, October 1 for Guitar; Williams (Columbia LP) 7:00 am BLUES HANGOVER Liszt: Grande Fantaisie symphonique on Themes from 11:00 am MEMORIAL CHURCH SERVICE Berlioz’s Lélio, for Piano and Orchestra, S. 120; Howard, Preacher: Professor Jonathan L. Walton, Plummer Professor Rickenbacher, Budapest Symphony Orchestra (Hyperion) of Christian Morals and Pusey Minister in The Memorial 6:00 pm MUSIC OF THE SOVIET UNION Church,. Music includes Kodály’s Missa brevis and Mozart’s The Eve of the Revolution. Ave verum corpus, K. 618. Scriabin: Sonata No. 7, Op. 64, “White Mass” and Sonata No. 9, 12:30 pm AS WE KNOW IT Op. 68, “Black Mass”; Hamelin (Hyperion) 1:00 pm CRIMSON SPORTSTALK Glazounov: Piano Concerto No. 2 in B, Op. 100; Ponti, Landau, 2:00 pm SUNDAY SERENADE Westphalian Orchestra of Recklinghausen (Turnabout LP) 6:00 pm HISTORIC PERFORMANCES Rachmaninoff: Vespers, Op. 37; Roudenko, Russian Chamber Prokofiev: Violin Concerto No. 2 in g, Op. -

Form in the Music of John Adams

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ridderbusch, Michael, "Form in the Music of John Adams" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6503. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6503 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch DMA Research Paper submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Theory and Composition Andrew Kohn, Ph.D., Chair Travis D. Stimeling, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Cynthia Anderson, MM Matthew Heap, Ph.D. School of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2017 Keywords: John Adams, Minimalism, Phrygian Gates, Century Rolls, Son of Chamber Symphony, Formalism, Disunity, Moment Form, Block Form Copyright ©2017 by Michael Ridderbusch ABSTRACT Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch The American composer John Adams, born in 1947, has composed a large body of work that has attracted the attention of many performers and legions of listeners. -

Sunday Classics Season Comes to a Thrilling Close As the RSNO Take Edinburgh Audiences on an Incredible Journey Through the Solar System

Press release for immediate use Sunday Classics season comes to a thrilling close as the RSNO take Edinburgh audiences on an incredible journey through the solar system Sunday Classics: The Planets: An HD Odyssey, with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra 3:00pm, Sunday 16 June 2019 The Planets: An HD Odyssey Richard Strauss - Also sprach Zarathustra (opening) Johann Strauss II - The Blue Danube JS Bach (orch. Stokowski) - Toccata and Fugue in D minor Beethoven - Symphony No. 7 (second movement) Williams - Main theme from Star Wars Holst - The Planets (Left: RSNO onstage at Usher Hall. Right: Ben Palmer) Images available to download here Holst’s mystical masterpiece with stunning NASA images of our solar system: a spectacular Sunday Classics Season finale. Take an unforgettable journey to the furthest reaches of the cosmos. With the visionary music of Holst’s The Planets, together with stunning NASA images of our solar system’s planets in high definition on the big screen in the gorgeous surroundings of the Usher Hall. From the galvanising military rhythms of Mars to the eerie beauty of Venus; from the majestic power of Jupiter to the mystical visions of Neptune – The Planets is a spectacular tribute to pioneering science, and also a glimpse into the hidden mysteries of astrology, all conveyed in some of Holst’s most evocative music. Combined with real-life, large-screen NASA pictures of the planets’ uncanny natural beauties, it’s an overwhelmingly powerful experience. Holst’s magical masterpiece is performed by the exceptional musicians of the Royal Scottish National Orchestra, directed by exciting young British conductor Ben Palmer. -

FRENCH SYMPHONIES from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

FRENCH SYMPHONIES From the Nineteenth Century To The Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman NICOLAS BACRI (b. 1961) Born in Paris. He began piano lessons at the age of seven and continued with the study of harmony, counterpoint, analysis and composition as a teenager with Françoise Gangloff-Levéchin, Christian Manen and Louis Saguer. He then entered the Paris Conservatory where he studied with a number of composers including Claude Ballif, Marius Constant, Serge Nigg, and Michel Philippot. He attended the French Academy in Rome and after returning to Paris, he worked as head of chamber music for Radio France. He has since concentrated on composing. He has composed orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. His unrecorded Symphonies are: Nos. 1, Op. 11 (1983-4), 2, Op. 22 (1986-8), 3, Op. 33 "Sinfonia da Requiem" (1988-94) and 5 , Op. 55 "Concerto for Orchestra" (1996-7).There is also a Sinfonietta for String Orchestra, Op. 72 (2001) and a Sinfonia Concertante for Orchestra, Op. 83a (1995-96/rév.2006) . Symphony No. 4, Op. 49 "Symphonie Classique - Sturm und Drang" (1995-6) Jean-Jacques Kantorow/Tapiola Sinfonietta ( + Flute Concerto, Concerto Amoroso, Concerto Nostalgico and Nocturne for Cello and Strings) BIS CD-1579 (2009) Symphony No. 6, Op. 60 (1998) Leonard Slatkin/Orchestre National de France ( + Henderson: Einstein's Violin, El Khoury: Les Fleuves Engloutis, Maskats: Tango, Plate: You Must Finish Your Journey Alone, and Theofanidis: Rainbow Body) GRAMOPHONE MASTE (2003) (issued by Gramophone Magazine) CLAUDE BALLIF (1924-2004) Born in Paris. His musical training began at the Bordeaux Conservatory but he went on to the Paris Conservatory where he was taught by Tony Aubin, Noël Gallon and Olivier Messiaen. -

A Festival of Fučík

SUPER AUDIO CD A Festival of Fučík Royal Scottish National Orchestra Neeme Järvi Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library Photo Music & Arts Lebrecht Julius Ernst Wilhelm Fučík Julius Ernst Wilhelm Fučík (1872 – 1916) Orchestral Works 1 Marinarella, Op. 215 (1908) 10:59 Concert Overture Allegro vivace – [ ] – Tempo I – Andante – Adagio – Tempo I – Allegro vivo – Più mosso – Tempo di Valse moderato alla Serenata – Tempo di Valse – Presto 2 Onkel Teddy, Op. 239 (1910) 4:53 (Uncle Teddy) Marche pittoresque Tempo di Marcia – Trio – Marcia da Capo al Fine 3 Donausagen, Op. 233 (1909) 10:18 (Danube Legends) Concert Waltz 3 Andantino – Allegretto con leggierezza – Tempo I – Più mosso – Tempo I – Tempo di Valse risoluto – 3:06 4 1 Tempo di Valse – 1:48 5 2 Con dolcezza – 1:52 6 3 [ ] – 1:25 7 Coda. [ ] – Allegretto con leggierezza – Tempo di Valse 2:08 8 Die lustigen Dorfschmiede, Op. 218 (1908) 2:34 (The Merry Blacksmiths) March Tempo di Marcia – Trio – [ ] 9 Der alte Brummbär, Op. 210 (1907)* 5:00 (The Old Grumbler) Polka comique Allegro furioso – Cadenza – Tempo di Polka (lentamente) – Più mosso – Trio. Meno mosso – A tempo (lentamente) – Più mosso – Meno mosso – Più mosso – Meno mosso – Più mosso – [Cadenza] – Più mosso 4 10 Einzug der Gladiatoren, Op. 68 (1899) 2:36 (Entry of the Gladiators) Concert March for Large Orchestra Tempo di Marcia – Trio – Grandioso, meno mosso, tempo trionfale 11 Miramare, Op. 247 (1912) 7:47 Concert Overture Allegro vivace – Andante – Adagio – Allegro vivace 12 Florentiner, Op. 214 (1907) 5:20 Grande marcia italiana Tempo di Marcia – Trio – [ ] 13 Winterstürme, Op. -

Téléchargez La Version

sm14-9_Cover_NoUPC.qxd 5/26/09 11:40 PM Page 1 www.scena.org sm14-9_pXX_layout_ADS.qxd 5/26/09 6:02 PM Page 2 sm14-9_pXX_layout_ADS.qxd 5/26/09 6:02 PM Page 3 ESPRIT ZEN Marie-Nicole Lemieux Philippe Jaroussky 6 titres dans Rinaldo Alessandrini la collection et autres Esprit Les albums Esprit Baroque, Esprit Sacré, Esprit Mélancolique, Esprit Zen, Esprit Ibé- rique et Esprit Romantique réunissent des œuvres exceptionnelles interprétées avec 99 brio par Marie-Nicole Lemieux, Philippe 12 ch. Jaroussky, Rinaldo Alessandrini et plusieurs autres. EXCLUSIVITÉ ARCHAMBAULT ! THE BEST OF BEATLES BAROQUE, DIANE DUFRESNE CHANTE KURT WEILL ET FORESTARE NOUVEAUTÉ Les pop ATMA Classique : trois CD ATMA pour le prix d’un. Forestare avec Richard Desjardins, Diane Dufresne chante Kurt 99 Weill, et les plus grands succès de la sé- 16 rie Beatles Baroque avec Les Boréades. pour les Parfait pour l’été ! 3 CD 1499 1099 MARI KODAMA, KENT NAGANO NAREH ARGHAMANYAN BEETHOVEN LISZT, RACHMANINOV Piano Concertos Nos. 1 & 2 Sonates 99 DVD 9ch. Autres titres également en vente ITALY, SWITZERLAND : FRANCE : PARIS, BURGUNDY, SOUTHERN TYROL AND TICINO PROVENCE, LOIRE... Musique de Beethoven Musique de Chopin CD 1499 4999 v 21CD MAGDALENA KOZENÁ, BERGONZI, DOMINGO, VENICE BAROQUE ORCHESTRA SCOTTO, FRENI ET AUTRES VIVALDI Verdi : Great Operas from La Scala Opera & Oratorios Arias La culture du divertissement 15 MAGASINS s!RCHAMBAULTCAss 15 LIBRAIRIES SERVICE AUX INSTITUTIONS ET ENTREPRISESs!RCHAMBAULT SIECA AGRÉÉES sm14-9_p4_TOC 5/27/09 12:41 PM Page 4 RÉDACTEURS FONDATEURS -

100 Years of Extraordinary Historical Highlights from the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra Archives

100 Years of Extraordinary Historical Highlights from the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra Archives 1910s 1915 – Through a $6,000 grant from the city of Baltimore, the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra is founded as a branch of the city’s Department of Municipal Music, making it the only major American orchestra to be fully funded as a municipal agency. 1916 – On February 11, the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra performs its inaugural concerts to a standing- room-only crowd at The Lyric, under the direction of Music Director Gustav Strube. All three concerts comprising the first season at the Lyric are sold out. 1920s 1924 – On February 16, the BSO hosts its first children’s concert. The Baltimore Symphony youth concert series is the first to be established by an American orchestra. 1926 – The Baltimore Symphony makes its initial broadcast performance on WBAL Radio. 1930s 1930 - George Siemonn becomes the second music director of the orchestra. He conducts his opening concert, with the musicians now numbering 83, on November 23. 1935 - In late February, George Siemonn reluctantly resigns as music director and is replaced by Ernest Schelling. Forty-four musicians apply for the position. Schelling is well-known for his children’s concert series at Carnegie Hall. 1937 - Sara Feldman and Vivienne Cohn become the first women to join the Baltimore Symphony. The older members of the orchestra are supportive, but union members picket the hall with signs saying, “Unfair to Men,” which is reported in the New York Times. 1937 - Ernest Schelling becomes ill and is replaced by Werner Janssen. The dynamic young conductor and his wife, the celebrated film star Ann Harding, receive an enthusiastic response when they arrive in Baltimore.